Design for Me?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Design for All' Versus 'One-Size-Fits-All': the Case Of

‘Design for All’ versus ‘One-Size-Fits-All’: the Case of Cultural Heritage 1 2 Daniela Fogli , Alberto Arenghi 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy [email protected] 2Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Architettura, Territorio e Ambiente e di Matematica Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy [email protected] Abstract. This paper would like to discuss the design trade-offs that might emerge during the development of technological solutions for promoting and enhancing the fruition of cultural heritage. To this aim, the paper briefly describes the UniBSArt4All project, which employs advanced interactive technologies, such as artwork recognition and wireless sensors, to obtain engaging and accessible visitor experiences customized to different users’ profiles. By reflecting on the project development and its preliminary results, the paper finally proposes a meta-design approach to inclusive design in the CH domain. Keywords: Cultural heritage, augmented reality, beacon, end-user development, meta-design, inclusive design, design for all 1 Introduction In our everyday life, we often encounter trade-offs, namely situations where we need to renounce to something in order to gain something else. Problem solving usually represents such a situation, in which a solution must be designed by taking into account both the goals one would like to satisfy and the different constraints that impose choosing among those goals. Therefore, usually design “is the identification, discussion and resolution of trade-offs” [15]. Indeed, as underlined by Gerhard Fischer, a design problem does not have a correct solution or a right answer, but the solution or the answer depends on the values and interests of the involved stakeholders [6][7]. -

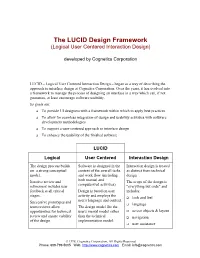

The LUCID Design Framework (Logical User Centered Interaction Design)

The LUCID Design Framework (Logical User Centered Interaction Design) developed by Cognetics Corporation LUCID – Logical User Centered Interaction Design – began as a way of describing the approach to interface design at Cognetics Corporation. Over the years, it has evolved into a framework to manage the process of designing an interface in a way which can, if not guarantee, at least encourage software usability. Its goals are: q To provide UI designers with a framework within which to apply best practices q To allow for seamless integration of design and usability activities with software development methodologies q To support a user-centered approach to interface design q To enhance the usability of the finished software LUCID Logical User Centered Interaction Design The design process builds Software is designed in the Interaction design is treated on a strong conceptual context of the overall tasks as distinct from technical model. and work flow (including design. both manual and Iterative review and The scope of the design is computerized activities). refinement includes user "everything but code" and feedback at all critical Design is based on user includes: stages. activity and employs the q look and feel user's language and context. Successive prototypes and q language team reviews allow The design model fits the opportunities for technical user's mental model rather q screen objects & layout review and ensure viability than the technical q navigation of the design implementation model. q user assistance © 1998, Cognetics Corporation, All Rights Reserved Phone: 609-799-5005 Web: http://www.cognetics.com Email: [email protected] An Introduction to the LUCID Framework Page 2 Over the past 30 years, several techniques for managing software development projects have been developed and documented. -

Design for All: Not Excluded by Design

A Friendly Rest Room: Developing Toilets of the Future for Disabled and Elderly People 7 J.F.M. Molenbroek et al. (Eds.) IOS Press, 2011 © 2011 The authors. All rights reserved. doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-752-9-7 Design for All: Not Excluded by Design Johan F.M. MOLENBROEKa,1, Theo J.J. GROOTHUIZENb, R. DE BRUINc a Faculty of Industrial Design – Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands b Design Consultant – Groothuizen Beheer bv, Rotterdam, The Netherlands c Erin Ergonomics and Industrial Design, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Abstract. Inclusive Design or Design for All refers to the design philosophy of including as many users groups as possible in the target population of a to-be- designed product and to be aware of the ones that are excluded. This paper explains about the history, current status and possibilities of Inclusive Design as strategy. Within the FRR-project this strategy was leading when design decisions had to be taken. The outcome is a truly Friendly Rest Room, fulfilling the needs of disabled and elderly in a non-stigmatizing manner, and thus favoured by us all. Keywords: Inclusive Design, Design for All, Universal Design 1. Introduction 1.1. The Need to Design for All In Europe and the Western world in general, the quality of life for its inhabitants has dramatically improved over the last couple of decades. The numbers of people that reach the age of 65 have been fast growing. For instance in the Netherlands 6% of the population in 1900 was aged 65+ to more than 12% in 2000 and perhaps 25% in 2050. -

Inclusive Design for Mobile Devices with WCAG and Attentional Resources in Mind

Linköping University | Department of Computer and Information Science Master’s thesis, 30 credits | Cognitive science Spring term 2020 | ISRN: LIU-IDA/KOGVET-A--20/010--SE Inclusive Design for Mobile Devices with WCAG and Attentional Resources in Mind An investigation of the sufficiency of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines when designing inclusively and the effects of limited attentional resources. Josefin Carlbring Tutor: Erik Marsja (IBL) Examinator: Arne Jönsson (IDA) Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – for a period of 25 years starting from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/hers own use and to use it unchanged for non-commercial research and educational purpose. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional upon the consent of the copyright owner. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure authenticity, security and accessibility. According to intellectual property law the author has the right to be mentioned when his/her work is accessed as described above and to be protected against infringement. For additional information about the Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its www home page: http://www.ep.liu.se/. © Josefin Carlbring ii iii Abstract When designing for the general population it is important to design inclusively in order to invite to participation in today’s digital society. -

Universal Design in Architectural Education: Who Is Doing It? How Is It Being Done?

Universal design in architectural education: Who is doing it? How is it being done? 1 1 1 Megan Basnak , Beth Tauke , Sue Weidemann 1IDeA Center, University at Buffalo—State University of New York, Buffalo, NY ABSTRACT: The World Health Organization estimates that over one billion people, or 15% of the world’s population, have some form of disability. As demographics change and the world’s population continues to age, this number is expected to dramatically increase. In response to this global trend, many designers, advocates, and anyone interested in making physical and visual environments more usable for people with diverse backgrounds and abilities have adopted the philosophy known as universal design (UD), inclusive design, or design for all. Despite the demonstrated need for designers who are knowledgeable in UD theory and practice, it seems that architecture programs in U.S. universities have been slow to adequately incorporate UD into their curricula. In an effort to gain a better understanding of the current state of UD content in architecture curricula, researchers distributed an online survey to architectural educators and administrators in 120 U.S. institutions with accredited degree programs. The study, sponsored by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), consisted of qualitative and quantitative questions that sought information related to the understanding, attitudes, and incorporation of UD into each participant’s curriculum. Responses were obtained from 463 participants representing 104 of the 120 surveyed schools. Quantitative analyses found relationships between perceived attitudes of administrators, faculty, and students and the effectiveness of UD components in a program. Qualitative findings were rich and complex, revealing great variability across schools, in terms of how, when (course level), and the degree to which UD aspects were incorporated into programs. -

9.2 MB Fort Mcnair Design Narrative

Design Narrative 100% Design Submission FY21 - McNair Group 01 Quarters 10 - 15 USACE Project reference: JBMHH Army Family Housing Project number: 60615576 June 09, 2021 Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Quality information Prepared Checked Verified by Approved by by by Blank Blank Blank Blank Krista Joshua Ryan Krista Kehrer Levy Horner/Troy Kehrer Project Metz Manager Revision History Revision Revision Details Authorized Name Position date 0 Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Distribution List # Hard PDF Association / Company Name Copies Required Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank blank Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Prepared for: USACE W912DR21BXXXX -W912DR19F0647 Vivian Wong 2 Hopkins Plaza Baltimore, MD 21201 Prepared by: Krista Kehrer Project Manager T: 703-682-4973 M: 703-867-7948 E: [email protected] AECOM 3101 Wilson Boulevard Arlington, VA 22201 aecom.com Copyright © 2019 by AECOM All rights reserved. No part of this copyrighted work may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of AECOM. Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family -

What Is Universal Design…Inclusive Design…Design-For-All?

What is universal design…inclusive design…design-for-all? …a framework for the design of places, things, information, communication and policy that focuses on the user, on the widest range of people operating in the widest range of situations without special or separate design. Or, more simply: Human-Centered design (of everything) with everyone in mind Universal Design Principles: Equitable Use: The design does not disadvantage or stigmatize any group of users. Flexibility in Use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. Simple, Intuitive Use: Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level. Perceptible Information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities. Tolerance for Error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions. Low Physical Effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably, and with a minimum of fatigue. Size and Space for Approach & Use: Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use, regardless of the user’s body size, posture, or mobility. [Developed by a group of US designers and design educators from five organizations in 1997. Principles are copyrighted to the Center for Universal Design, School of Design, State University of North Carolina at Raleigh. The Principles are in use internationally.] Relationship between Legally Mandated Accessibility & Inclusive Design Legally mandated requirements for accessible design, within a civil or human rights context, provide a vital basis for autonomy and equal opportunity for people with disabilities. -

DESIGN THINKING TACTICS and IDEA GENERATION STRATEGIES in a BRAINSTORMING SESSION Naz A.G.Z

METUDESIGN JFA THINKING 2015/2 TACTICS AND IDEA GENERATION DOI:METU 10.4305/METU.JFA.2015.2.1 JFA 2015/2 1 (32:2) 1-17 USAGE OF DESIGN THINKING TACTICS AND IDEA GENERATION STRATEGIES IN A BRAINSTORMING SESSION Naz A.G.Z. BÖREKÇİ* Received: 05.09.2014; Final Text: 09.03.2015 INTRODUCTION Keywords: Brainstorming, problem area, design thinking tactics, idea generation A short-term educational project on corrugated cardboard shelf-ready strategies, solution areas. packaging for baby food jars was carried out as part of an elective graduate course. The design project involved thirteen graduate students, who worked on the project for 18 hours spread across six weeks. The process began with a brainstorming session after the design brief was distributed. It was observed during the session that the participants used various tactics to initiate discussion in their rounds, displaying individual abilities to provide the session with input to which the other participants could respond. Besides, participants followed certain strategies for a continuous and cumulative discussion resulting in the determination of major solution areas. This motivated a search for answers to the following questions through an analysis of the documentation of the session: • What were the tactics and strategies used by the participants? • For which purposes and how were these tactics and strategies used? • What were the reflections of these tactics and strategies on the discussions? The aim of this paper is to provide insights into the individual and collective efforts in using tactics for generating discussions and strategies for generating ideas in design thinking. The paper begins with an overview of the design thinking literature on tactics and strategies. -

Teaching Accessibility and Design

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 12-2012 Teaching Accessibility and Design-For-All in the Information and Communication Technology Curriculum: Three Case Studies of Universities in the United States, England, and Austria Paul Ryan Bohman Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Bohman, Paul Ryan, "Teaching Accessibility and Design-For-All in the Information and Communication Technology Curriculum: Three Case Studies of Universities in the United States, England, and Austria" (2012). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1369. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1369 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING ACCESSIBILITY AND DESIGN-FOR-ALL IN THE INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY CURRICULUM: THREE CASE STUDIES OF UNIVERSITIES IN THE UNITED STATES, ENGLAND, AND AUSTRIA by Paul R. Bohman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Education (Curriculum and Instruction) Approved: J. Nicholls Eastmond, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Rowland, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor Co-Major Professor Martha L. Whitaker, Ph.D. Susan A. Turner, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Martha T. Dever, Ed.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2012 ii Copyright © 2012 Paul Ryan Bohman All rights reserved iii ABSTRACT Teaching Accessibility and Design-For-All in the Information and Communication Technology Curriculum: Three Case Studies of Universities in the United States, England, and Austria by Paul R. -

Ensuring Universal Design in ICT-Solutions

Ensuring Universal Design in ICT- Solutions Towards Identifying Critical Success Factors Susanne Klungland Harder Master in Interaction Design Submission date: June 2017 Supervisor: Miriam Begnum, ID Norwegian University of Science and Technology Department of Design Foreword This master thesis makes up the finale 30 credits of a two year master study in Interaction Design at NTNU Gjøvik. The study aims to provide insights into the practices regarding successful implementation of Universal Design in Norwegian ICT-projects, by building on a previous student work published at the NOKOBIT Conference in 2016 (Appendix E). First and foremost I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor, for remarkable support and guidance throughout the development and completion of this research, as well as for the rewarding collaboration in the second part of this study. Thank you for many fruitful discussions and advice you have given during this process. I would also like to direct a warm thank you to all of the informants for their participation in my study - their contribution is the basis of this thesis - and for their continuous work to ensure usability for all. Last, but not least, I would like to take this opportunity to thank my colleagues, friends and family who have all supported, encouraged and believed in me through a rather stressful time – this has meant a lot to me. A special thanks to Adrian, who has been particularly patient, supportive and positive. Oslo, June 1st, 2017 Susanne Klungland Harder i ii Abstract Universal Design (UD) of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) is a fundamental principle that seeks to ensure accessibility for all. -

Design for All in a Commercial Perspective

Design for all in a commercial perspective Onny Eikhaug The Norwegian Design Council The Norwegian Design Council (NDC) was established in 1963 by the Norwegian Trade Council and the Confederation of Norwegian Business and Industry (NHO). Today the NDC is organised as a foundation financed by the the Ministry of Trade and Industry, through the provision of business consultancy and from its own, standalone projects. The ambition of the NDC is to promote design as a strategic tool for innovation, in order to offer greater competitive advantage and profitability to Norwegian trade and industry. The NDC achieves this by delivering design-related business advice to Norwegian enterprises . It disseminates its work through printed and online publication, radio, news items, web pages, exhibitions, design awards, and national and international conferences. For several years, the NDC has emphasized the importance of Design for All whilst working with Norwegian industry. A four-year programme, named Innovation for All, was initiated to support industrial growth by contributing to and supporting new product development processes based on Design for All principles. One of the goals of this programme is to identify and demonstrate the innovation potential of this approach and to develop products and services that are user friendly and attractive for all. A key objective of the programme is to provide relevant knowledge of Norwegian conditions for industry and design communities, as well as offering motivating and effective approaches that can be easily adopted and implemented in everyday practice. It is also vital to prepare Norwegian companies for forthcoming legislation that will require products and services to be more socially inclusive and cater for people with different ages and capabilities. -

Beyond User Centered Design Co-Creative Emergent Approaches in the Industrial Design Discipline

BEYOND USER CENTERED DESIGN CO-CREATIVE EMERGENT APPROACHES IN THE INDUSTRIAL DESIGN DISCIPLINE Kevin Shankwiler, IDSA / Claudia B. Rebola Georgia Institute of Technology [email protected] / [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION New understanding of people as users has forced the industrial design discipline to change. Since its origins, industrial design has traditionally attempted to design products for “most” - the target market where new opportunities are identified through market research. In this realm, the emphasis was on fabrication technologies that could produce products affordable for most users. More recently, however, there has been a shift in focus by applying universal design principles with the goal of creating products usable by more people. Universal design principles allowed designers to expand that focus and design for “more.” Currently, most industrial design institution curricula apply user-centered approaches, where universal design is the backbone. However, these methods are still not enough to allow designers to reach "all." In an attempt to accommodate demands of design for all, new methods have been injected into the design process. Linking the two aforementioned approaches advances a new business model in the design discipline. This paper discusses a co-creative emergent approach in the industrial design discipline that allow an understanding of users as individuals and therefore deliver more targeted design solutions for “all”. Novel design methods are discussed including participatory design and parametric modeling linked with digital fabrication. The authors discuss the links and relationships between the methods and how they complement each other throughout the course of the design process. The significance of this paper is to advance a new model of delivering better-suited products and services to the user needs within the discipline.