INTERVIEW with CLIFF BRENNER MARCH 26, 1997 Feinstein Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Reaction, and Reform: the Three Rs of Philadelphia School Politics, 1965-1971 Author(S): Jon S

Race, Reaction, and Reform: The Three Rs of Philadelphia School Politics, 1965-1971 Author(s): Jon S. Birger Source: The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 120, No. 3 (Jul., 1996), pp. 163-216 Published by: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20093045 . Accessed: 22/03/2011 22:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=hsp. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. -

Intergroup Relations Between Blacks and Latinos in Philadelphia, 1950S to 1980S

“THE BATTLE FOR HARMONY”: INTERGROUP RELATIONS BETWEEN BLACKS AND LATINOS IN PHILADELPHIA, 1950S TO 1980S by Alyssa M. Ribeiro BS, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2004 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Alyssa M. Ribeiro It was defended on March 18, 2013 and approved by Laurence Glasco, Associate Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Associate Professor, Department of History Rob Ruck, Professor, Department of History Joe W. Trotter, Professor, Department of History, Carnegie Mellon University Dissertation Advisor: Edward K. Muller, Professor, Department of History ii Copyright © by Alyssa M. Ribeiro 2013 iii “THE BATTLE FOR HARMONY”: INTERGROUP RELATIONS BETWEEN BLACKS AND LATINOS IN PHILADELPHIA, 1950S TO 1980S Alyssa M. Ribeiro, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation is a case study that explores black and Latino relations in North Philadelphia neighborhoods from the 1950s through the 1980s. It draws upon community organization records, local government documents, newspapers, and oral histories. In the fifties and sixties, scarce housing, language barriers, Puerto Ricans’ ambiguous racial identity, and slow adaptation by local institutions contributed to racial tension and social segregation. But from the late sixties through the late seventies, black-Latino relationships markedly improved. During this crucial decade, blacks and Latinos increasingly drew upon their shared circumstances to form strategic alliances. They used grassroots organizing to pressure existing institutions, focusing on basic issues like schools, housing, and police. -

Interview with Thomas M. Foglietta, Esq. June 24, 1980 the First

Interview with Thomas M. Foglietta, Esq. June 24, 1980 The first question is how did your father come to be a Republican leader in Philadelphia and what role did he play in that regard? Well, I would think that he became a leader in Philadelphia because at that time when my family first came to this country the Republican pa±y was the party in power. My grandmother and grandfather came here as teenagers in the 1870's or early 1880's and they were married here in Philadelphia and they always used to tell me that they got married in Independence Hall because City Hall was not completed yet and — again, in those days if you were Catholic you could not have only a religious ceremony, you had to have a religious ceremony and a civil ceremony. So they had to go to Independence Hall to be married. And I think that what evolved was the community leader was the person who became involved in politics and in those days there wasn't really a Democratic party to speak of, so my dad went on to become not only the leader of his family, because he was the oldest of five children when his father was killed in a bicycle accident in about 1901. He then had to leave school and go to work. He worked in those days in Center City because as you know, although we lived in South Philadelphia and he lived in South Philadelphia — the family lived on Climber Street, which is the first street below Fitzvjater — that ,is the first street of South Philadelphia, where Center City ends. -

RIZZO VIDEO AUDIO (Scene of Rizzo Funeral at the Basilica up Full :10

RIZZO VIDEO AUDIO (scene of Rizzo funeral at the Basilica up full :10 - :15) NARRATION OVER SOUNDBITE “HE WAS CALLED THE SUPER COP, THE CISCO KID, THE BIG BAMBINO, THE GENERAL. AND HE WAS CALLED A LOT WORSE THINGS. OFTEN ACCUSED OF DIVIDING THE CITY HE LOVED, FRANK LAZZARO RIZZO DREW MOURNERS AND ONLOOKERS FROM EVERY PART OF THE CITY AND BEYOND AT HIS FUNERAL ON JULY 19TH, 1991. Lynne Abraham: “He believed he was larger than life. But no one is larger than life..." NARRATION “LOVE. AWE. FEAR. HATRED. FRANK RIZZO ATTRACTED STRONG, CONFLICTING EMOTIONS. FOR SOME, HE REPRESENTED SECURITY, STABILITY AND STRENGTH. FOR OTHERS, HE EMBODIED REPRESSION, BRUTALITY AND THE CORRUPTION OF MACHINE POLITICS…” Charles Bowser “Frank Rizzo believed in good guys and bad guys, and he was the sheriff, and it was his job to get rid of the bad guys. And, and, and it was quick draw kind of justice . it was kind of naïve to say the least, but that really was the way he saw the world. He was the sheriff, and he knew what was right, and he was trying to do what was right…” Tom Sugrue 1 “He’s looking out onto a city who’s economy is being profoundly transformed, which ordinary folks simply don’t understand. Why are the jobs leaving Philadelphia? Why are our neighborhoods changing in composition? These are big forces that are shaping all of urban America in the period, and Rizzo offers a simple answer. And that answer is: ‘Outside forces are threatening your security and stability, and we need to step in, intervene and aggressively stop the march of these outside forces…’ “ Fred Voigt: “Philadelphia prides itself on being a city of neighborhoods. -

The Politics of Transportation in Philadelphia, 1946-1984

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: “LET THE PEOPLE HAVE A VICTORY”: THE POLITICS OF TRANSPORTATION IN PHILADELPHIA, 1946-1984 Jacob Kobrick, Ph.D., 2010 Directed By: Professor Robyn L. Muncy Department of History Urban transportation planning in the United States underwent important changes in the decades after World War II. In the immediate postwar period, federal highway engineers in the Bureau of Public Roads dominated the decision-making process, creating a planning regime that focused almost entirely on the building of modern expressways to relieve traffic congestion. In the 1960s, however, local opposition to expressway construction emerged in cities across the nation, reflecting growing discontent with what many citizens perceived to be a closed planning process that resulted in the destruction of urban neighborhoods, environmental degradation, and inadequate attention paid to alternative modes of transportation. Local freeway protestors found allies in the new U.S. Department of Transportation, which moved in the mid-1960s to absorb the Bureau of Public Roads and support legislation promoting a planning process more open to local input as well as a greater emphasis on federal aid for urban mass transportation. The changing culture of transportation planning produced a series of freeway revolts, resulting in the cancellation or modification of interstate highway projects, in major American cities. Changes in transportation planning played out differently in every city, however. This dissertation examines controversies over Philadelphia’s major expressway projects – the Schuylkill Expressway, the Delaware Expressway, and the never-built Crosstown Expressway, in addition to major mass transit developments such as the city’s subsidization of the commuter railroads, the creation of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, and the building of a railroad tunnel known as the Center City Commuter Connection, in order to trace the evolution of the city’s transportation politics between 1946 and 1984. -

Union League Archives Archives

Union League archives Archives Last updated on January 09, 2012. Union League of Philadelphia 2011.03.01 Union League archives Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................4 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................5 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Architectural drawings.............................................................................................................................8 Books......................................................................................................................................................69 Broadsides.............................................................................................................................................. 69 Charters................................................................................................................................................. -

July 15 Issue

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday, July 15, 2003 Volume 50 Number 1 www.upenn.edu/almanac Penn, he has held faculty President Rodin: positions at the University Stepping Down in June 2004 of Chicago, the Universi- Dr. Judith Rodin, ty of Maryland and recently president since 1994, an- he was the Scholar-in-Resi- nounced that she intends dence and Professor at the to step down from the of- Center for Social Work Ed- fice when she completes ucation, Widener University. her 10-year term in June Dr. Schwartz has consulted 2004. The June 20 an- around the world on social nouncement came fol- work practice and mental lowing the meeting of the health treatment issues. In full Board of Trustees. addition, he has been a visit- Carol Spigner Joseph McBride Arthur Schwartz “Serving Penn these ing lecturer at major univer- past years has been an sities in the U.S. and abroad. extraordinary privilege Social Work Teaching Awards He has authored and co-authored many articles and an exhilarating ex- The 2003 recipients of the School of Social and book chapters. His books include Depres- Judith Rodin perience,” Dr. Rodin Work’s Excellence in Teaching Awards are Dr. sion, Theories and Treatments: Psychological, said. “This is a remark- Carol Wilson Spigner, a member of the stand- Biological and Social Perspectives, (with Ruth able community of amazing depth and breadth, ing faculty; Joseph McBride, and Dr. Arthur M. Schwartz); The Behavior Therapies; and So- and I am grateful to the Trustees for their sup- Schwartz, members of the part-time faculty. -

December 5, 1976 My Name Is Thacher Longstreth. I'm 57 Years

Interview with Thacher Longstreth December 5, 1976 My name is Thacher Longstreth. I'm 57 years old. I live at thecorner of 300 West Highland Ave with my wife, Nancy. I'm the father of four children, all adults, and 11 grandchildren in the process of becoming adults. I've resided in Chestnut Hill since September of 1950, when I returned;after four years with Life magazine in Detroit. I was born and brought up in Haverford and my family has lived in the Philadelphia area ever since Bartholomew Longstreth came here with William Penn in the late 1600's. We are ninth generation Quakers and have been closely affiliated with many aspects of Philadelphia life for a long, long time. I was educated at the Haverford School in Haverford, where my father had also graduated and was the first Longstreth in four generations to not go on to Haverford College. Traditionally the family had always gone on to Haverford. I had illusions of athletic grandeur, which were never realized, but I wanted a forum that was slightly larger than that of a small Quaker college in which to strut my stuff, so I ended up in Princeton where I played three major sports and where I enjoyed the advantages of a scholarship which enabled me to go through Princeton at a time when my family had no money whatsoever and where I was involved in a great deal of student employment to make that education possible. I sold sandwiches. I waited on table. I was involved in a number of campus agencies, both from a management and from a sales standpoint. -

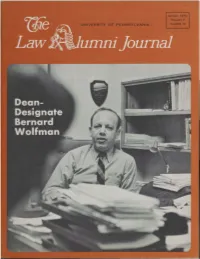

PENNSYLVANIA NUMBER Ill from the Dean's Desk: Alumni Support Lauded

SPRING 1870 VOLUME V UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA NUMBER Ill From the Dean's Desk: Alumni Support Lauded The alumni have recently had word from this quarter granted. Let me say with great emphasis that I do through the medium of the Dean's Annual Report for not. I am justly known as an outspoken individual 1968-69. It will not be long until my service as Dean who has raised his voice frequently on controversial will have come to a close. I hope that I can make the issues of public concern. In doing so, I have tried to Annual Report, which will follow-that for 1969-70- act responsibly, but I cheerfully leave it to others to a sort of "summation," which will be more than ret judge whether I have. The point, however, is that the rospective. Meanwhile, I seize, with much pleasure, alumni, as a group, are people of size and generosity this opportunity ( 1 ) to speak in a personal vein to the of spirit, which is something I admire and cherish be ,alumni and (2) to bespeak for the able colleague, who yond measure. is to succeed me as There will be a changing of the guard on July 1, 1970. Dean, the magnifi Professor Bernard Wolfman, of the Law Faculty, will cent alumni com assume the responsibilities of the deanship. I know of mitment to the wel no better way to indicate the intellectual stature of the fare of the School man than to point out that within but a few short years which has sustained after moving from active and highly successful law and inspirited us practice into law teaching, he achieved recognition as throughout all my one of the outstanding teachers of Federal Taxation in years at the institu the country.