Utopia Europa? Transition and Responses to EU Rural Development Initiatives in the Republic of Macedonia's Tikveš Wine Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide for Stakeholders in Sustainible Tourism

2018 GUIDE FOR STAKEHOLDERS IN SUSTAINIBLE TOURISM MKD In cooperation with A.I.A.M AdefisJuventad International ICDET CENET pg. 1 The World Tourism Organization’s definition of sustainable tourism Sustainable tourism development guidelines and management practices areapplicable to all forms of tourism in all types of destinations, including mass tourism and the various niche tourism segments. Sustainability principles refer to the environmental, economic and socio- cultural aspects of tourism development, and a suitable balance must be established between these three dimensions to guarantee its long-term sustainability. Who this Guide is for The Guide is primarily aimed at governments, at both national and local levels. It is also relevant to international development agencies, NGOs and the private sector, to the extent that they are affected by, and can affect, tourism policy and its implementation. This Guidebook was developed as product within the Erasmus + project” Cheese and Wine and tourism will shine-, funded by the European Union Purpose and scope of the Guide The purpose of this document is to provide governments with guidance and a framework for the development of policies for more sustainable tourism as well as a toolbox of instruments that they can use to implement those policies. -Making tourism more sustainable within itself should contain the following 12 components objectives . 1.Employment quality 2.Community Wellbeing 3.Biological diversity 4.Economic Viability 5.Local Control 6.Physical integrity 7.Environmental purity 8.Local Prosperity 9.Visitor Fulfillment 10.Cultural Richness 11.Resource Efficiency 12.Social Equity pg. 2 Employment opportunity Social Comunity equity well being Resource Biological Efficiency diversity Cultural Components of Economic Richness sustainible tourism Viability Visitor Local Fullfillmen t Control Local Physical Prosperity Integrity Enviromenta l Purity pg. -

Enotourism in North Macedonia – Current State and Future Prospects

6 - 40000 GEOGRAPHY AND TOURISM, Vol. 8, No. 1 (2020), 65-80, Semi-Annual Journal eISSN 2449-9706, ISSN 2353-4524, DOI: 10.36122/GAT20200806 © Copyright by Kazimierz Wielki University Press, 2020. All Rights Reserved. http://geography.and.tourism.ukw.edu.pl Sylwia Kwietniewska1a, Przemysław Charzyński1b 1 Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Faculty of Earth Sciences and Spatial Management ORCID: a https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3226-4778, b https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1467-9870 Corresponding author: a [email protected], b [email protected] Enotourism in North Macedonia – current state and future prospects Abstract: North Macedonia, the country located in the middle of the Balkan Peninsula, is known for its wine-growing culture, and is divided into three wine regions with around 80 operating wineries. It is also surrounded by countries where vines have been grown and wine produced since the ancient times. The paper presents the history of North Macedonia as a wine-growing country, and provides an overview of its enotourism offer. An inventory of winery offers based on their official websites and Facebook profiles was performed, including the analysis of the surveys conducted among enotour- ists. Said surveys targeted participants of the Tikveški Grozdober festival in particular. It should also be mentioned that several of them were completed by Macedonian residents. The survey results outline a socio-demographic profile of the enotourists coming to this country and their enotouristic experience. The article sheds light on the history of winemaking and presents wine regions in North Macedonia. Keywords: wine tourism, wine regions, North Macedonia, Balkans, wine tourist profile 1. -

Characterization and Classification of Wines from Grape Varieties Grown in Turkey

CHARACTERIZATION AND CLASSIFICATION OF WINES FROM GRAPE VARIETIES GROWN IN TURKEY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Engineering and Sciences of İzmir Institute of Technology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Food Engineering by İlknur ŞEN July 2014 İZMİR We approve the thesis of İlknur ŞEN Examining Committee Members: _________________________ Prof. Dr. Figen TOKATLI Department of Food Engineering, İzmir Institute of Technology ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Durmuş ÖZDEMİR Department of Chemistry, İzmir Institute of Technology ___________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Banu ÖZEN Department of Food Engineering, İzmir Institute of Technology _________________________ Prof. Dr. Yeşim ELMACI Department of Food Engineering, Ege University _________________________________ Prof. Dr. Ahmet YEMENİCİOĞLU Department of Food Engineering, İzmir Institute of Technology 11 July 2014 _________________________ Prof. Dr. Figen TOKATLI Supervisor, Department of Food Engineering İzmir Institute of Technology _________________________________ ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Ahmet YEMENİCİOĞLU Prof. Dr. R. Tuğrul SENGER Head of the Department of Dean of the Graduate School of Food Engineering Engineering and Sciences ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank to my supervisor Prof. Dr. Figen TOKATLI for her guidance and support throughout the thesis study. I also would like to express my thanks to the committee members, Prof. Dr. Durmuş ÖZDEMİR and Assoc. Prof. F. Banu ÖZEN for their valuable comments and advices. I would like to thank to the research centers; Biotechnology and Bioengineering Research Center and Environmental Reference Research and Development Center for providing the HPLC and ICP-MS instruments. I also would like to thank to IYTE Scientific Research Projects Commission for funding my thesis with the projects 2008- IYTE-18 and 2010-IYTE-07. -

The Macedonian Wine Cluster (Pdf)

The Macedonian Wine Cluster Harvard Business School Microeconomics of Competitiveness, Spring 2006 Instructor: Prof. Michael E. Porter Project Group: Bartol Letica Dan Doncev Ersin Esen Nem Mijic Susanne Cassel May 5, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Macedonia’s Economy and National Business Environment 3 1.0 Country overview 3 1.1. Political situation 3 1.2. Economic analysis 4 2.0 National Diamond Analysis 8 2.1. Factor Conditions 9 2.2. Context for Firm Strategy and Rivalry 9 2.3. Demand Conditions 10 2.4. Related and Supporting Industries 10 3.0 Country Strategy and recommendations 11 II. The Macedonian Wine Cluster 13 4.0 Overview of the Macedonian Wine Cluster 13 4.1 History 13 4.2 Cluster Map 14 4.3. Key Features of the Macedonian Wine Cluster 15 4.4 Winemaking in Macedonia 16 4.4.1 Grape Growing/Procurement 16 4.4.2 Crushing, Fermentation and Aging 17 4.4.3 Bottling and Packaging 18 4.4.4 Production, Sales, Marketing and Distribution 18 5.0 Cluster Diamond Analysis 20 5.1. Factor Conditions 21 5.2. Context for Firm Strategy and Rivalry 22 5.3. Demand Conditions 23 5.4. Related and Supporting Industries 24 6.0 Cluster recommendations 27 III. Bibliography and Disclosures 31 2 I. Macedonia’s Economy and National Business Environment 1. Country overview 1.1. Political situation Macedonia was proclaimed a sovereign and independent state on September 17, 1991 after a national referendum. Its history has been characterised by a centuries-long struggle of the Macedonian people for a free and independent state, symbolized by the state’s motto “liberty or death”. -

ENLARGEMENT – BILATERAL MEETINGS WINE Non-Exhaustive List of Issues and Questions to Facilitate Preparations for Bilateral Meetings COUNTRY:TURKEY

AGRI-C.3 E.Q. Page 1 of 20 ENLARGEMENT – BILATERAL MEETINGS WINE Non-exhaustive list of issues and questions to facilitate preparations for bilateral meetings COUNTRY:TURKEY A. Technicalities of wine-making 1. Which are the most important grape varieties (both vitis vinifera and hybrid varieties, indication of ratio between the two)? Under the “Communique No.2005/39” published in Official Gazette dated August 11, 2005 and numbered 25903, the varieties are listed as below. Grape Varieties for Red Wine: Grape Varieties for White Wine: -Adakarası -Alicante Bouschet - Bornova Misketi - Dökülgen -Boğazkere - Hasandede -Cabernet Sauvignon - Kabarcık - Cinsault - Maccabeu -Horozkarası - Narince -Kalecik Karası - Chardonnay -Karasakız - Rumi -Öküzgözü - Semillon -Papaz Karası - Sultani Çekirdeksiz -Pinot Noir -Yapıncak -Sergi Karası -Syrah -Merlot In additon to the varieties above, the varieties mentioned below are also harvested in Turkey. Grape Varieties for Red Wine: Grape Varieties for White Wine: Wine: -Carignan - Beylerce -Çal Karası -Clairette -Gamay - Colombard -Grenache -Emir AGRI-C.3 E.Q. page 2 of 20 -Karalahana - Riesling -Mourvévedre - Sungurlu -Pinot Meunier - Ugni Blanc -Cabernet Franc - Vasilaki - Moltepulciano - Sauvignon Blanc -Portugieser -Chenin - Sangiovese -Sylvaner -Akdimrit All the grape varieties mentioned above are vitis vinifera. 2. Do grape varieties need administrative authorisation before planting? -No, grape varieties do not need administrative authorisation before planting. 3. Is grape growing limited to certain areas? -No, grape growing is not limited to certain areas. 4. Which are the permitted oenological practices and treatments for wine? There does not exist any special legislation concerning oenological practices, in the form that is regulated by Council Regulation 1493/1999. Nonetheless, certain additives which are mentioned at the Annex 4 of the concerned Regulation, are contained in the “Turkish Food Codex - Communique on Food Additives Excluding Sweeteners and Colorants” (O.G. -

Macedonian Wineries Are Raising a Glass to Successful Entry Into the Swedish Market

Macedonian Wineries are Raising a Glass to Successful Entry into the Swedish Market AgBiz is supporting the Macedo- Sweden has one of the most regulated wine markets in Europe, if not nian wine industry by providing in the world, due to the state monopoly in alcoholic drinks retailing. capacity building and compre- SystemBolaget is the only legal off-trade outlet for alcoholic drinks, hensive competitiveness en- and operates some 400 stores across the country. Its buying commit- hancement activities. AgBiz has tee analyzes local and international trends and establishes the range facilitated joint presentations of of wines to be offered for sale. The 485 registered suppliers can then Macedonian wines in various tender for procurement listings, but their wines face stringent quality high potential markets by organ- checks before they are accepted. Swedish consumers are becoming izing specialized promotional more in favor of fruity, fresh and non barrique style wines, produced events in Poland, Holland, the by modern technology. In the new tenders there is also a trend toward Czech Republic and via participa- organic wines and unusual blends. tion in the most relevant wine trade fairs such as ProWein AgBiz and Macedonian wineries have identified this trend as a great Germany and the Moscow and opportunity to penetrate the Swedish market. Therefore, AgBiz sup- London Wine Fairs. ported Macedonian export ready wineries to contact the most relevant Swedish importers and monopoly representatives. In coordination with the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Economy (MAFWE), the Macedonian Embassy and the Economic Promoter in Sweden, AgBiz facilitated a Macedonian Wine Tasting event that took place in th Stockholm on 27 January at the Scandic Sergel Plaza Hotel. -

Study on WINE Tourismin

Study on WINE Tourism in the REPUBLIC OF NORTH MACEDONIA Created by: Working Team from TURISTIKA Skopje: Dejan Metodijeski, Oliver Filiposki, Emilija Todorovic, Milena Taleska, Georgi Michev, Cedomir Dimovski, Nako Taskov, Kristijan Dzambazovski, Nikola Cuculeski, Mladen Micevski. Photos: Under the consent of wineries included in the survey, for the needs of the Study. Design: Stojan Kaevski Proofreading: Tole Belchev Disclaimer: This study has been developed under the 2019 Tourism Development Programme. The opinions and views stated in this publication do not necessarily reflect the opinions and views of the Ministry of Economy of the Republic of North Macedonia CONTENTS FOREWORD .........................................................................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................................5 METHODOLOGICAL FRAME OF STUDY DEVELOPMENT ...........................................................................................................7 I. GLOBAL TRENDS IN WINE TOURISM .......................................................................................................................................9 1. Characteristics of wine tourism ..........................................................................................................................................9 -

The Potential Future for Wine Tourism in the Balkans

American Journal of Tourism Management 2014, 3(1B): 34-50 DOI: 10.5923/s.tourism.201402.05 Eastern Promises: The Potential Future for Wine Tourism in the Balkans John E. Hudelson Assistant Professor of Global Wine Studies, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, Washington Abstract The Balkan countries have become a new focus for international wine writers. The dozen nations that lie totally or partially within the Balkan Peninsula are culturally and politically diverse, but all share in a millennia-old love of wine and its production. More than 400 autochthonous varieties of wine grapes are grown on the peninsula. Some, such as Plavac Mali, Zelenac and Vranac are basically unknown in the rest of the world but produce fine wine in most of the Balkan nations. There would appear to be an immense potential for greater development of wine tourism in the region, which with time could become a boon to its new market-based economies. This paper, based on visits to Balkan wineries and interviews with wine makers, academics and other leaders in the wine and wine tourism industries, is a survey of the present tourism infrastructures, the wine trade organizations and regional wine histories. It explores the capacity of wine industries to develop tourism as a component of their operations. In the end, suggestions are made that may help develop the Balkans as an international wine destination. Keywords Wine tourism, Balkan national economies, Tourism development This paper surveys wine tourism in major Balkan 1. Introduction wine-producing nations using available government, public and industry data, initial survey interviews and first-hand The Balkan Peninsula has for millennia been the cultural observations. -

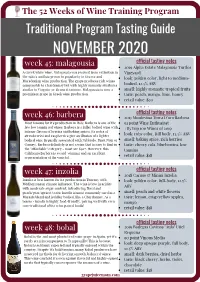

November Traditional Program Tasting Notes

The 52 Weeks of Wine Training Program Traditional Program Tasting Guide NOVEMBER 2020 week 45: malagousia official tasting notes 2019 Alpha Estate Malagouzia Turtles A Greek white wine, Malagousia was rescued from extinction in Vineyard the 1980's and has grown in popularity in Greece and look: golden color, light to medium- Macedonian wine production. The grape produces rich wines comparable to Chardonnay but with highly aromatic attributes bodied, 12.5% ABV similar to Viognier or Gewurztraminer. Malagousia is now a smell: highly aromatic tropical fruits prominent grape in Greek wine production. taste: peach, mango, lime, honey retail value: $20 official tasting notes week 46: barbera 2017 Montevina Terra D'oro Barbera Most famous for it's production in Italy, Barbera is one of the 91 point Wine Enthusiast few low tannin red wines. Barbera is a fuller bodied wine with #83 Top 100 Wines of 2019 intense flavors of berries and baking spices. Its notes of look: ruby color, full body, 13.5% ABV strawberries and raspberries give an illusion of a lighter bodied wine (typically associated with Nebbiolo, Pinot Noir or smell: baking spice, rich berries Gamay). Barbera definitely is not a wine that is easy to find in taste: cherry cola, blueberries, low the "affordable" category - most are $30+. However, this tannins California Barbera is award-winning and an excellent retail value: $18 representation of the varietal. official tasting notes week 47: inzolia 2018 Caruso & Minini Inzolia Inzolia is best known for its production in Tuscany with look: golden color, full-body, 12.5% Mediterranean climate influence. -

Wine and Wine Tourism in Macedonia

(JPMNT) Journal of Process Management – New Technologies, International Vol. 4, No.3, 2016. WINE AND WINE TOURISM IN MACEDONIA Assoc. Prof. Cane Koteski, PhD University “Goce Delcev”, Faculty of Tourism and Business Logistics, „Krste Misirkov“ 10-A, 2000 Stip, Makedonija, [email protected] Assoc. Prof. Zlatko Jakovlev, PhD University “Goce Delcev”, Faculty of Tourism and Business Logistics, „Krste Misirkov“ 10-A, 2000 Stip, Makedonija, [email protected] Dragana Soltirovska, master „Franc Rozman“ 106, 1300 Kumanovo, Makedonija, [email protected] Professional Paper doi:10.5937/jouproman4-11128 Abstract : Wine (Latin: vinum) is an alcoholic the country together with the sun, the food beverage obtained by the fermentation of the grapes, and the endless natural beauty. Under the the fruit of the vine plant. In Europe, according to legal regulations, the wine is the product obtained old storytellers who will meet the exclusively by full or partial fermentation of fresh plantations Vineyard biggest secret of taste grapes, clove or not, or of grape must. The of wines from Macedonia's sun to the transformation of grapes into wine is called region of Central Macedonia gives its vinification. The science of wine is called oenology. specificity of each grape. When you start In some other parts of the world, the word wine can be true of alcohol obtained from other types of fruit. from Veles to Kavadarci, Negotino, Demir These wines are referred to as fruit wines, or wear a Kapija to Gevgelija you through vineyards name by which the fruit is used for obtaining them and flooding large and small wineries that (for example apple wine). -

Study ANALYSIS of the REGULATORY FRAMEWORK AND

Study ANALYSIS OF THE REGULATORY FRAMEWORK AND ECONOMICS OF THE WINE SECTOR Darko Jakšić, author 5/27/19 This study is prepared through the Cooperation for Growth (CFG) project implemented by Cardno Emerging Markets USA, Ltd. 1 CONTENT 1. ANALYSIS OF THE REGULATORY FRAMEWORK OF THE WINE SECTOR 4 1.1. Wine Legislation in Serbia 4 1.2. EU Wine Legislation 5 1.3. Compliance of Serbian Wine Legislation with EU Regulations 7 1.4. Basic Problems in Serbian Viticulture and Wine Production and Major Obstacles for 11 Implementation of EU acquis in the Wine Sector 1.5. Strategic Policy Directions for the Viticulture and Wine Production Sector and 19 Recommend Regulatory Changes 1.6. The Most Important Benefits of Harmonizing the Viticulture and Wine Production Sector 30 with EU Regulations and Removing Obstacles 2. ANALYSIS OF ECONOMICS OF THE SECTOR AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STRATEGIC 31 POLICY OPTIONS 2.1. Production Volume, Prices, Export and Import of Wine 31 2.2. World Wine Market and Comparison with Selected Countries of the Region and EU 41 Countries 3. REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVE WINE ASSOCIATIONS 49 3.1. Current Capacities and Activities of Wine Associations 49 3.2. Possibilities for Strengthening the Capacities for Wine Associations 50 4. WINE QUALITY POLICY 51 4.1. Common Information about EU PDO/PGI System 51 4.2. Benefits of Wine Geographical Indications 53 4.3. Suggestions for Helping Local Producers with Protection of PDOs and PGIs 54 4.4. Obligations and Financial Costs for Producers of Wines with Geographical Indications 65 5. SUGGESTIONS OF GOOD PRACTICES FOR FUTURE DEVELOPMENT OF THE WINE SECTOR 66 LITERATURE 67 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS CEFTA Central European Free Trade Association G.I. -

Macedonia Competitiveness Activity Quarterly Report January 2006 – March 2006

Macedonia Competitiveness Activity Quarterly Report January 2006 – March 2006 Ul. Bukureska 133b Skopje, Macedonia Tel: (389 2) 309-1711; Fax: (389 2) 307-9158 MACEDONIA COMPETITIVENESS ACTIVITY Quarterly Report: January – March 2006 Executive Summary NECC: The National Entrepreneurship and Competitiveness Council is broadening its membership as part of an overall sustainability strategy. Three new organizations joined the NECC at the annual assembly meeting in February 2006: the Chamber of Commerce of Republic of Macedonia, the Chamber of Commerce of Western Macedonia and the European Business Association. Through the president of the management board, Deputy Prime Minister Minco Jordanov, the NECC is working on deeper involvement of the public sector in the work of the Council and has already assured support from the Prime Minister. PED: MCA’s Public Education Department (PED) continued to foster strong relationships with news media by offering success stories featuring clusters and individual cluster members to the media outlets as MCA’s activities generate more results. The close cooperation established with the Total news portal, the only web-based portal for business news in Macedonia, resulted with posting of several short articles on MCA and clusters’ results. PED’s involvement in planning and organizing cluster special events contributed to high attendance by relevant private, public sector representatives, members of the international donor community, as well as media coverage and visibility of USAID-sponsored activities. Lamb and Cheese: LTM (Lamb to Market) was set up by the two sheep breeders cooperatives in their efforts to enter the Greek lamb market and increase profitability and competitiveness of Macedonian lamb producers.