From Global to Local: Human Mobility in the Rome Coastal Area in the Context of the Global Economic Crisis*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solano Et Al. Laborest 18 2019 Layout 1

Local Development: Urban Space, Rural Space, Inner Areas Sviluppo Locale: Spazio Urbano, Spazio Rurale, Aree Interne GIS and Remote Sensing Techniques for the Assessment of Biomass Resources for energy Uses in Rome Metropolitan Area ANALISI GEOSPAZIALI PER LA VALUTAZIONE DELLA BIOMASSA ALL’INTERNO DI UN AREA PROTETTA NEL CONTESTO DELL’AREA METROPOLITANA DI ROMA* Francesco Solanoa, Nicola Colonnab, Massimiliano Maranib, Maurizio Pollinob aDipartimento di AGRARIA, Università Mediterranea, Via dell'Università 25, 89124 - Reggio Calabria, Italia bENEA, Centro Ricerche Casaccia, Via Anguillarese 301, 00123 - Roma, Italia [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The Metropolitan city of Roma Capitale (Italy) represents a vast area, including many municipalities with the purpose to strength the promotion and coordination of economic and social development. Natural Parks included in the Metropolitan area are able to provide ecosystem services and resources such as agricultural and forest products as well as biomass resources that could be an opportunity to replace fossil fuels, make the city more climate friendly and, at the same time, to relaunch the sustainable management of forest that are often abandoned and prone to degradation risk. The goal of this paper is to investigate and update the actual distribution of the main forest types of the Bracciano-Martignano Regional Natural Park, through GIS and Remote Sensing techniques, in order to assess the biomass potential present in the forest areas. Results showed that there are about 20,000 t of woody biomass per year available and confirmed the importance of Sentinel-2 satellite data for vegetation applications, reaching a high overall accuracy. -

Towards Implementing S3.Current Dynamics and Obstacles in the Lazio Region

TOWARDS IMPLEMENTING S3.CURRENT DYNAMICS AND OBSTACLES IN THE LAZIO REGION A. L. Palazzo1 and K. Lelo2 1 Department of Architecture, Roma Tre University of Rome, Via Madonna dei Monti, 40, 00184 Roma, Italy 2 Department of Economics, Roma Tre University of Rome, Via Silvio d’Amico, 77, 00145 Roma, Italy Email: [email protected] Abstract: The Lazio Region is carrying out a re-industrialization policy following the Europe 2020 targets for economic growth, known as Smart Specialization Strategy (S3). This paper frames industrial policy settings dating back to the second half of the 20th Century in the light of current processes and institutional efforts to set a new season for Industry in Lazio Region. Subsequently, relying upon demographic and socio-economic dynamics over the last two decades, new features in settlement patterns and sector-specific obstacles to sustainable development are addressed with a major focus on the Metropolitan area of Rome (the former Province of Rome). In conclusion, some remarks are drawn mindful of the new globalization wave affecting ‘supply chains’ of goods and business services from all over the world, of current trends and innovative approaches liable to envisage ‘territory’ as an opportunity rather than a cost. Difficulties in making different opinions to converge are evident. The proper ground to make it happen should be prepared by a governance able to support place-based inherent ‘entrepreunerial discovery processes’, while providing negotiating practices framed by general and sectoral policies, and communication approaches to ensure transparency and participation of public at large. Keywords: Lazio Region, Metropolitan Area, S3, Settlement Patterns, Sustainability Scenarios, Territorial Innovation 1. -

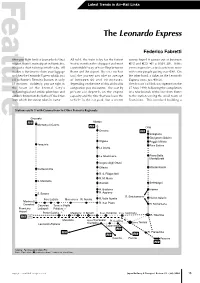

The Leonardo Express

Feature Latest Trends in Air–Rail Links The Leonardo Express Federico Fabretti After your flight lands at Leonardo da Vinci All told, the train is by far the fastest survey found it comes out at between Airport, Rome’s main airport in Fiumicino, (not to mention the cheapest and most €12 and €22 (€1 = US$1.28). If this it is just a short train trip into the city. All comfortable) way of travelling between seems expensive, a taxi costs even more it takes is the time to claim your luggage Rome and the airport. By car, coach or with some people paying over €40. On and then the Leonardo Express whisks you taxi, the journey can take an average the other hand, a ticket on the Leonardo off to Rome’s Termini Station in only of between 60 and 90 minutes, Express costs just €9.50. 31 minutes. Suddenly, you are right in depending on the time of day and traffic The first air–rail link was opened on the the heart of the Eternal City’s congestion you encounter. The cost by 27 May 1990, following the completion archaeological and artistic splendours and private car depends on the engine of a new branch of the line from Rome a stone’s throw from the Baths of Diocletian capacity and the time that you leave the to the station serving the small town of from which the station takes its name. vehicle in the car park, but a recent Fiumicino. This involved building a Stations on Fr 1 with Connections to Other Ferrovia Regionale Grosseto Fr 5 Viterbo Montalto di Castro Fr 3 Orte Cesano Fr 1 Simigliano Gavignano Sabino Olgiata Poggio Mirteto Tarquinia Fara Sabina La Storta La Giustiniana Piana Bella Montelibretti Ipogeo degli Ottavi Ottavia Monterotondo Civitavecchia R. -

The Routes of Taste

THE ROUTES OF TASTE Journey to discover food and wine products in Rome with the Contribution THE ROUTES OF TASTE Journey to discover food and wine products in Rome with the Contribution The routes of taste ______________________________________ The project “Il Camino del Cibo” was realized with the contribution of the Rome Chamber of Commerce A special thanks for the collaboration to: Hotel Eden Hotel Rome Cavalieri, a Waldorf Astoria Hotel Hotel St. Regis Rome Hotel Hassler This guide was completed in December 2020 The routes of taste Index Introduction 7 Typical traditional food products and quality marks 9 A. Fruit and vegetables, legumes and cereals 10 B. Fish, seafood and derivatives 18 C. Meat and cold cuts 19 D. Dairy products and cheeses 27 E. Fresh pasta, pastry and bakery products 32 F. Olive oil 46 G. Animal products 48 H. Soft drinks, spirits and liqueurs 48 I. Wine 49 Selection of the best traditional food producers 59 Food itineraries and recipes 71 Food itineraries 72 Recipes 78 Glossary 84 Sources 86 with the Contribution The routes of taste The routes of taste - Introduction Introduction Strengthening the ability to promote local production abroad from a system and network point of view can constitute the backbone of a territorial marketing plan that starts from its production potential, involving all the players in the supply chain. It is therefore a question of developing an "ecosystem" made up of hospitality, services, products, experiences, a “unicum” in which the global market can express great interest, increasingly adding to the paradigms of the past the new ones made possible by digitization. -

Elenco Corsisti Plenaria - Cerveteri - E

SCUOLA POLO I.C.CENA - ELENCO CORSISTI PLENARIA - CERVETERI - E. MATTEI Sede di servizio Cognome Nome 2 CERVETERI ALEO FILIPPA 3 MANZIANA ALUNNI ELISABETTA 4 LADISPOLI AMATO SABRINA 5 LADISPOLI AMICI SIMONA 6 BRACCIANO ANTOGNONI GABRIELE 7 LADISPOLI ANTONELLI PATRIZIA 8 LADISPOLI ARTUSI DANIELA 9 LADISPOLI AUTOLITANO ANNA MARIA 10 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA AVELLINO MICHELINA 11 LADISPOLI BALDINI FRANCESCA 12 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA BALSAMO VENERANDA 13 CERVETERI BANDIERA TIZIANA 14 LADISPOLI BAORTO MARIKA 15 LADISPOLI BARIOLI RENATO 16 LADISPOLI BARLAFANTE VALERIA 17 BRACCIANO BASSANELLI EMANUELE 18 LADISPOLI BERNARDI DANIELA 19 LADISPOLI BERTOLLI DOMENICO AMLETO 20 LADISPOLI BLASI LAURA 21 BRACCIANO BOCCHINI BRUNO 22 LADISPOLI BOMARSI FRANCESCA 23 LADISPOLI BONACCI CHIARA 24 LADISPOLI BONANNO MARIA 25 TREVIGNANO ROMANO BOTTINI ROSSELLA 26 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA BRACCI FRANCESCO 27 LADISPOLI BREGAMO LUCIA ELENA MARIA 28 BRACCIANO BUCCIARELLI SILVIA 29 LADISPOLI BUCCIERO LAURA 30 LADISPOLI CADONI MARIA GRAZIA 31 LADISPOLI CALATO BRUNA 32 CERVETERI CALZECCHI ONESTI STEFANO 33 BRACCIANO CAMELE PAOLA 34 LADISPOLI CAMPANELLA DORIANA 35 LADISPOLI CANDELORI STEFANIA 36 BRACCIANO CANGIAMILA SALVATORE 37 BRACCIANO CAPALOZZA GIADA 38 LADISPOLI CAPODACQUA ANNA 39 CERVETERI CAPONE GIOVANNA 40 CERVETERI CAPORALE ALESSIA 41 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA CAPUANO VITA MARIA 42 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA CARISSIMI FRANCESCA 43 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA CAROSI CRISTINA 44 BRACCIANO CAROTENUTO GAETANA 45 BRACCIANO CATARINOZZI LOREDANA 46 CERVETERI CATERINA MARCELLA 47 BRACCIANO CATINI DANIELE 48 -

A Large Ongoing Outbreak of Hepatitis a Predominantly Affecting Young Males in Lazio, Italy; August 2016 - March 2017

RESEARCH ARTICLE A large ongoing outbreak of hepatitis A predominantly affecting young males in Lazio, Italy; August 2016 - March 2017 Simone Lanini1☯, Claudia Minosse1☯, Francesco Vairo1, Annarosa Garbuglia1, Virginia Di Bari1, Alessandro Agresta1, Giovanni Rezza2, Vincenzo Puro1, Alessio Pendenza3, Maria Rosaria Loffredo4, Paola Scognamiglio1, Alimuddin Zumla5, Vincenzo Panella6, Giuseppe Ippolito1*, Maria Rosaria Capobianchi1, Gruppo Laziale Sorveglianza Epatiti Virali (GLaSEV)¶ a1111111111 a1111111111 1 Dipartimento di Epidemiologia Ricerca Pre-Clinica e Diagnostica Avanzata, National Institute for Infectious diseases Lazzaro Spallanzani, Rome, Italy, 2 Department of Infectious Diseases, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, a1111111111 Rome, Italy, 3 Azienda Sanitaria Locale Roma 1 Dipartimento di PrevenzioneÐU.O.S. Controllo Malattie e a1111111111 Gestione Flussi Informativi, Rome, Italy, 4 Azienda Sanitaria Locale Roma 3 Servizio di Igiene e Sanità a1111111111 Pubblica Profilassi delle malattie infettive e parassitarie, Rome, Italy, 5 Division of Infection and Immunity, University College London and NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, UCL Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom, 6 Direzione Regionale Salute e Politiche Sociali, Regione Lazio, Rome, Italy ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. ¶ Membership of Gruppo Laziale Sorveglianza Epatiti Virali (GLaSEV) is provided in the Acknowledgments. OPEN ACCESS * [email protected] Citation: Lanini S, Minosse C, Vairo F, Garbuglia A, Di Bari V, Agresta A, et al. -

1 Dipartimento IV Servizio 3 “Tutela

Protocollo: CMRC-2019-0142199 - 26-09-2019 11:16:48 Dipartimento IV Servizio 3 “Tutela Aria ed Energia Bando pubblico per la concessione di contributi ad utenti di impianti termici a uso domestico che intendano sostituire la caldaia obsoleta con una di nuova generazione ad elevato risparmio energetico ed a basso impatto ambientale nei Comuni della Città metropolitana di Roma Capitale aventi una popolazione fino a 40.000 abitanti (D.G.P. 95/15 dell’11 Aprile 2012) – Rev. 09/2019 Art . 1 (Finalità dell’iniziativa) La Città Metropolitana di Roma Capitale, subentrata per gli effetti della Legge 7 Aprile 2014 n. 56, alla Provincia di Roma , promuove e realizza iniziative a sostegno dello sviluppo e l’uso corretto delle risorse naturali e lo sviluppo di un’economia dell’innovazione ambientale con azioni rivolte a contrastare i cambiamenti climatici, in coerenza con gli obiettivi fissati dal Protocollo di Kyoto. Il progetto “provincia di Kyoto” è rivolto a coinvolgere attivamente le città europee nel percorso verso la sostenibilità energetica ed ambientale. L'iniziativa, impegna le città europee a predisporre un Piano di Azione di Sostenibilità Energetica vincolante con l'obiettivo di ridurre di oltre il 20% le proprie emissioni di gas serra attraverso politiche e misure locali che aumentino l'impiego di energia da fonti rinnovabili. Nell’ambito di applicazione degli obiettivi rientra il controllo sul rendimento energetico degli impianti termici, la cui disciplina attuativa è contenuta nel Piano di Risanamento della Qualità dell’Aria di cui al D. Lgs. 351/1991 approvato dalla Regione Lazio con D.C.R. n. -

Measuring Urban Subsidence in the Rome Metropolitan Area (Italy) with Sentinel-1 SNAP-Stamps Persistent Scatterer Interferometry

remote sensing Article Measuring Urban Subsidence in the Rome Metropolitan Area (Italy) with Sentinel-1 SNAP-StaMPS Persistent Scatterer Interferometry José Manuel Delgado Blasco 1,*, Michael Foumelis 2, Chris Stewart 3 and Andrew Hooper 4 1 Grupo de Investigación Microgeodesia Jaén (PAIDI RNM-282), Universidad de Jaén, 23071 Jaén, Spain 2 BRGM–French Geological Survey, 45060 Orleans, France; [email protected] 3 Future Systems Department, Earth Observation Programmes, European Space Agency (ESA), 00044 Frascati, Italy; [email protected] 4 Institute of Geophysics and Tectonics, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 8 January 2019; Published: 11 January 2019 Abstract: Land subsidence in urban environments is an increasingly prominent aspect in the monitoring and maintenance of urban infrastructures. In this study we update the subsidence information over Rome and its surroundings (already the subject of past research with other sensors) for the first time using Copernicus Sentinel-1 data and open source tools. With this aim, we have developed a fully automatic processing chain for land deformation monitoring using the European Space Agency (ESA) SentiNel Application Platform (SNAP) and Stanford Method for Persistent Scatterers (StaMPS). We have applied this automatic processing chain to more than 160 Sentinel-1A images over ascending and descending orbits to depict primarily the Line-Of-Sight ground deformation rates. Results of both geometries were then combined to compute the actual vertical motion component, which resulted in more than 2 million point targets, over their common area. Deformation measurements are in agreement with past studies over the city of Rome, identifying main subsidence areas in: (i) Fiumicino; (ii) along the Tiber River; (iii) Ostia and coastal area; (iv) Ostiense quarter; and (v) Tivoli area. -

Roma in Transizione

R O M A I N TRANSIZIONE G o v e r n o , s t r a t e g i e , m e t a b o l i s m i e q u a d r i d i v i t a di una metropoli a cura di Alessandro Coppola Gabriella Punziano PLANUM PUBLISHER | www.planum.net Roma-Milano ISBN 9788899237110 Volume pubblicato digitalmente nel mese di novembre 2018 Pubblicazione disponibile su www.planum.net | Planum Publisher R O M A I N TRANSIZIONE G o v e r n o , s t r a t e g i e , m e t a b o l i s m i e q u a d r i d i v i t a di una metropoli a cura di Alessandro Coppola Gabriella Punziano VOLUME 1 PLANUM PUBLISHER | www.planum.net A Sandra Annunziata, che aveva fatto di Roma la sua città. E che a Roma aveva studiato e lottato per città più giuste e dignitose. Continueremo, ancor più di prima, ad avere bisogno di tutto il tuo entusiasmo. Roma in Transizione. Governo, strategie, metabolismi e quadri di vita di una metropoli A cura di Alessandro Coppola e Gabriella Punziano Seconda edizione riveduta e corretta febbraio 2019 Prima edizione novembre 2018 Pubblicazione disponibile su www.planum.net, Planum Publisher Foto di copertina: © Francesca Cozzi ISBN 9788899237134 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording or other wise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. -

(Agro Pontino, Central Italy): New Constraints on the Last Interglacial

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The archaeological ensemble from Campoverde (Agro Pontino, central Italy): new constraints on the Last Received: 29 June 2018 Accepted: 14 November 2018 Interglacial sea level markers Published: xx xx xxxx F. Marra1, C. Petronio2, P. Ceruleo3, G. Di Stefano2, F. Florindo1, M. Gatta4,5, M. La Rosa6, M. F. Rolfo4 & L. Salari2 We present a combined geomorphological and biochronological study aimed at providing age constraints to the deposits forming a wide paleo-surface in the coastal area of the Tyrrhenian Sea, south of Anzio promontory (central Italy). We review the faunal assemblage recovered in Campoverde, evidencing the occurrence of the modern fallow deer subspecies Dama dama dama, which in peninsular Italy is not present before MIS 5e, providing a post-quem terminus of 125 ka for the deposit hosting the fossil remains. The geomorphological reconstruction shows that Campoverde is located within the highest of three paleosurfaces progressively declining towards the present coast, at average elevations of 36, 26 and 15 m a.s.l. The two lowest paleosurfaces match the elevation of the previously recognized marine terraces in this area; we defne a new, upper marine terrace corresponding to the 36 m paleosurface, which we name Campoverde complex. Based on the provided evidence of an age as young as MIS 5e for this terrace, we discuss the possibility that previous identifcation of a tectonically stable MIS 5e coastline ranging 10–8 m a.s.l. in this area should be revised, with signifcant implications on assessment of the amplitude of sea-level oscillations during the Last Interglacial in the Mediterranean Sea. -

Urban Shrinkage, Land Consumption and Regional Planning in a Mediterranean Metropolitan Area

Sustainability 2015, 7, 11980-11997; doi:10.3390/su70911980 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Case Report Desperately Seeking Sustainability: Urban Shrinkage, Land Consumption and Regional Planning in a Mediterranean Metropolitan Area Luca Salvati 1, Agostino Ferrara 2, Ilaria Tombolini 1,*, Roberta Gemmiti 3, Andrea Colantoni 4, and Luigi Perini 5 1 Italian Council of Agricultural Research and Economics (CREA), Via della Navicella 2, I-00184 Rome, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 School of Agricultural, Forest, Food and Environmental Sciences, University of Basilicata, Via dell'Ateneo Lucano 10, I-85100 Potenza, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Methods and Models for Territory, Economy and Finance, Sapienza University of Rome, Via del Castro Laurenziano 9, I-00161 Rome, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Agriculture, Forest, Nature and Energy (DAFNE), University of Tuscia, Via S. Camillo de Lellis snc Viterbo, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Italian Council of Agricultural Research and Economics (CREA), Via del Caravita 7a, I-00186 Rome, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-06-700-5413; Fax: +39-06-700-5711. Academic Editor: Marc A. Rosen Received: 5 July 2015 / Accepted: 20 August 2015 / Published: 28 August 2015 Abstract: Land degradation has expanded in the Mediterranean region as a result of a variety of factors, including economic and population growth, land-use changes and climate variations. The level of land vulnerability to degradation and its growth over time are distributed heterogeneously over space, concentrating on landscapes exposed to high human pressure. -

Roma E Provincia

Studi Odontoiatrici Indirizzo Cap Città Provincia ALBANO LAZIALE Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00041 MARCO AGUIARI CORSO MATTEOTTI 196 00041 ALBANO LAZIALE RM CIMINO E PELLECCHIA STUDIO ASSOCIATO PIAZZA GIOSUE' CARDUCCI 20 00041 ALBANO LAZIALE RM CERVETERI Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00052 CERRONE CLAUDIO VIA LEOMBRUNI 10 00052 CERVETERI RM CIVITAVECCHIA Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00053 D'AVENIA FABIO VIA TOGLIATTI 13/4 00053 CIVITAVECCHIA RM BOCCACCI MASSIMO VIA ROMA, 19 00053 CIVITAVECCHIA RM SERVIZI PREVENZIONE DENTALE SAS FERRARI E. VIALE GUIDO BACCELLI 36 00053 CIVITAVECCHIA RM STEFANO MARZIALE VIALE GUIDO BACCELLI 121 00053 CIVITAVECCHIA RM COLLEFERRO Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00034 PARODI CARLO VIA A. GRANDI 52 00034 COLLEFERRO RM FIANO ROMANO Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00065 DOMINICI ANTONINO VIA PALMIRO TOGLIATTI 116 00065 FIANO ROMANO RM FORMELLO LE RUGHE Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00060 LA BELLA LUCIANO C.C. ODISSEA 2000, VIALE AFRICA 84 00060 FORMELLO LE RUGHE RM GENZANO DI ROMA Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00045 MASSA PIO MARIA LEONARDO CORSO DON GIOVANNI MINZONI 39 00045 GENZANO DI ROMA RM GROTTAFERRATA Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00046 GIANNETTI ANGELO VIA DELLA COSTITUENTE, 5 00046 GROTTAFERRATA RM VALENTI SALVATORE VIA ROMA 28/A 00046 GROTTAFERRATA RM LADISPOLI Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00055 D'ALESSANDRO CLAUDIO VIA REGINA ELENA 18 00055 LADISPOLI RM MACCARESE Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00057 RICCI GABRIELE VIA ROSPIGLIOSI,16 00057 MACCARESE RM MARINO Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00047 D'ERRICO BENIAMINO C.SO TRIESTE 67 00047 MARINO RM MENTANA Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00013 MENDUNI DE ROSSI ATTILIO VIA REATINA 171 00013 MENTANA RM MONTEROTONDO Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00015 TURSI ALFREDO VIA XXV APRILE 3 00015 MONTEROTONDO RM NETTUNO Elenco Studi Odontoiatrici nel CAP 00048 DENTAL MEDICA SNC VIA S.