Towards Implementing S3.Current Dynamics and Obstacles in the Lazio Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guida Ai Sentieri Del Parco Dei Castelli Romani

Guida ai sentieri del Parco con la descrizione dettagliata dei sentieri completa di carte scala 1:15.000 Pubblicazione ad impatto zero in collaborazione con la Sezione C.A.I. di Frascati La nuova collana delle Guide del Parco è una delle molteplici ini- ziative che il Parco dei Castelli Romani ha realizzato nell’ambito delle attività di comunicazione e valorizzazione del territorio. Mi preme ringraziare il direttore Roberto Sinibaldi per l’attenzione prestata alle attività di Comunicazione, che hanno consentito all’Ente Parco uno straordinario salto di qualità sia in termini di servizi resi al cittadino sia in termini di autorevolezza acquisita. Il Patrimonio naturale e culturale e le bellezze del territorio vanno salvaguardate e difese perché rappresentano l’investimento per il presente e il futuro delle popolazioni che lo abitano. L’opportunità è dunque rappresentata proprio dal vincolo: mag- giore è l’attenzione alla tutela, maggiore sono i frutti, anche eco- nomici, che possono essere raccolti. Questo concetto, tanto semplice quanto efficace, ha rappresenta- to il principio ispiratore dell’azione del Parco in questi ultimi anni, del quale il direttore è stato l’energico interprete. Il Presidente del Parco Gianluigi Peduto E R A Roma C FIRENZE - MILANO L s. as Anagnina A2 f. si U no V I A N T U S C A U A O L T O S A T R A N A D A O R O M D A - R Monte Porzio Catone N A P O O L I C C c a t i A a s R F r a E o m D f . -

Partenza Arrivo Ora Partenza Ora Arrivo Instradamento Nome Transito

Ora Ora Nome Ora Entrata h Entrata h Uscita h Uscita h Uscita h Partenza Arrivo Instradamento Stagionalità Frequenza partenza arrivo transito transito 8 10 12.40 13.30 14.20 VELLETRI FS ROMA ANAGNINA 04.15 05.14 ACQUA LUCIA-GENZANO-GENZANO (Carabinieri)-ARICCIA (VIA ALBANO 04.45 SCOLASTICO LMMGV--- PAGLIAROZZA)-ALBANO LAZIALE-DUE SANTI-S.MARIA MOLE- LAZIALE VIA CAPANNELLE- ROMA ANAGNINA NETTUNO POLIGONO 04.30 05.53 AEROPORTO di CIAMPINO-FRATTOCCHIE-ALBANO LAZIALE- ALBANO 04.52 SCOLASTICO LMMGV--- ALBANO PADRI SOMASCHI-CECCHINA-OSPEDALE CASTELLI LAZIALE ROMANI-APRILIA FS-LAVINIO FS- VELLETRI FS ROMA ANAGNINA 04.55 05.55 ACQUA LUCIA-GENZANO-GENZANO (Carabinieri)-ARICCIA (VIA ALBANO 05.26 SCOLASTICO LMMGV--- PAGLIAROZZA)-ALBANO LAZIALE-DUE SANTI-S.MARIA MOLE- LAZIALE VIA CAPANNELLE- NETTUNO POLIGONO ROMA ANAGNINA 04.30 05.54 NETTUNO STAZ.FS-ANZIO staz.FS-LAVINIO FS-APRILIA FS- ALBANO 05.33 SCOLASTICO LMMGV--- OSPEDALE CASTELLI ROMANI-CECCHINA-ALBANO LAZIALE- LAZIALE FRATTOCCHIE- ROMA ANAGNINA LATINA 05.15 07.00 FRATTOCCHIE-ALBANO LAZIALE-GENZANO LICEO-VELLETRI FS- ALBANO 05.37 SCOLASTICO LMMGV--- CISTERNA- LAZIALE VELLETRI FS ROMA ANAGNINA 05.10 06.02 GENZANO-ALBANO LAZIALE-FRATTOCCHIE- ALBANO 05.41 SCOLASTICO LMMGV--- LAZIALE LANUVIO FS ROMA ANAGNINA 05.25 06.16 LANUVIO-S.LORENZO RM-GENZANO (I Ferri)-GENZANO- ALBANO 05.50 SCOLASTICO LMMGV--- GENZANO (Carabinieri)-ARICCIA (VIA PAGLIAROZZA)-ALBANO LAZIALE PADRI SOMASCHI-CASTEL GANDOLFO- LARIANO (P.ZA BRASS) ROMA ANAGNINA 05.20 06.20 VELLETRI-GENZANO-ALBANO LAZIALE-FRATTOCCHIE- ALBANO 05.55 -

The Leonardo Express

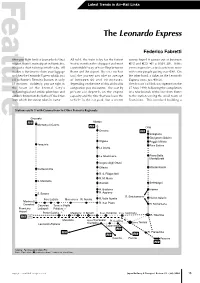

Feature Latest Trends in Air–Rail Links The Leonardo Express Federico Fabretti After your flight lands at Leonardo da Vinci All told, the train is by far the fastest survey found it comes out at between Airport, Rome’s main airport in Fiumicino, (not to mention the cheapest and most €12 and €22 (€1 = US$1.28). If this it is just a short train trip into the city. All comfortable) way of travelling between seems expensive, a taxi costs even more it takes is the time to claim your luggage Rome and the airport. By car, coach or with some people paying over €40. On and then the Leonardo Express whisks you taxi, the journey can take an average the other hand, a ticket on the Leonardo off to Rome’s Termini Station in only of between 60 and 90 minutes, Express costs just €9.50. 31 minutes. Suddenly, you are right in depending on the time of day and traffic The first air–rail link was opened on the the heart of the Eternal City’s congestion you encounter. The cost by 27 May 1990, following the completion archaeological and artistic splendours and private car depends on the engine of a new branch of the line from Rome a stone’s throw from the Baths of Diocletian capacity and the time that you leave the to the station serving the small town of from which the station takes its name. vehicle in the car park, but a recent Fiumicino. This involved building a Stations on Fr 1 with Connections to Other Ferrovia Regionale Grosseto Fr 5 Viterbo Montalto di Castro Fr 3 Orte Cesano Fr 1 Simigliano Gavignano Sabino Olgiata Poggio Mirteto Tarquinia Fara Sabina La Storta La Giustiniana Piana Bella Montelibretti Ipogeo degli Ottavi Ottavia Monterotondo Civitavecchia R. -

Rankings Municipality of Formello

9/29/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links ITALIA / Lazio / Province of Roma / Formello Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH ITALIA Municipalities Powered by Page 2 Affile Stroll up beside >> L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Formello AdminstatAgosta logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Albano Laziale FrascatiITALIA Allumiere Gallicano nel Lazio Anguillara Sabazia Gavignano Anticoli Corrado Genazzano Anzio Genzano di Roma Arcinazzo Romano Gerano Ardea Gorga Ariccia Grottaferrata Arsoli Guidonia Montecelio Artena Jenne Bellegra Labico Bracciano Ladispoli Camerata Nuova Lanuvio Campagnano di Lariano Roma Licenza Canale Magliano Monterano Romano Canterano Mandela Capena Manziana Capranica Marano Equo Prenestina Marcellina Carpineto Marino Romano Mazzano Casape Romano Castel Gandolfo Mentana Castel Madama Monte Compatri Castel San Monte Porzio Pietro Romano Catone Castelnuovo di Monteflavio Porto Montelanico Cave Montelibretti Cerreto Laziale Monterotondo Cervara di Montorio Powered by Page 3 Roma Romano L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Cerveteri Moricone Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Ciampino MorlupoITALIA Ciciliano Nazzano Cineto Romano Nemi Civitavecchia Nerola Civitella San Nettuno Paolo Olevano Colleferro Romano Colonna Palestrina Fiano Romano Palombara Sabina -

The Routes of Taste

THE ROUTES OF TASTE Journey to discover food and wine products in Rome with the Contribution THE ROUTES OF TASTE Journey to discover food and wine products in Rome with the Contribution The routes of taste ______________________________________ The project “Il Camino del Cibo” was realized with the contribution of the Rome Chamber of Commerce A special thanks for the collaboration to: Hotel Eden Hotel Rome Cavalieri, a Waldorf Astoria Hotel Hotel St. Regis Rome Hotel Hassler This guide was completed in December 2020 The routes of taste Index Introduction 7 Typical traditional food products and quality marks 9 A. Fruit and vegetables, legumes and cereals 10 B. Fish, seafood and derivatives 18 C. Meat and cold cuts 19 D. Dairy products and cheeses 27 E. Fresh pasta, pastry and bakery products 32 F. Olive oil 46 G. Animal products 48 H. Soft drinks, spirits and liqueurs 48 I. Wine 49 Selection of the best traditional food producers 59 Food itineraries and recipes 71 Food itineraries 72 Recipes 78 Glossary 84 Sources 86 with the Contribution The routes of taste The routes of taste - Introduction Introduction Strengthening the ability to promote local production abroad from a system and network point of view can constitute the backbone of a territorial marketing plan that starts from its production potential, involving all the players in the supply chain. It is therefore a question of developing an "ecosystem" made up of hospitality, services, products, experiences, a “unicum” in which the global market can express great interest, increasingly adding to the paradigms of the past the new ones made possible by digitization. -

Call for Papers

2015 IAA Planetary Defense Conference: 13-17 April 2015, Frascati, Italy www.pdc2015.org Call for Papers The 2015 PDC will include an impact threat exercise, where participants will simulate the decision-making process for developing deflection and civil defense responses to a threat posed by hypothetical asteroid 2013 PDC15. Information on the evolution of the threat up to the date of the conference will be posted at a website to be announced. Attendees are invited to use 2013 PDC15 as a subject for their own exercises and for papers that might be presented at the conference. Priority slots for presentation of papers focused on aspects of the 2013 PDC15 threat will be available. The final period of the threat’s evolution will be provided in periodic updates during the conference, and participants will develop a set of actionable recommendations based on that information. In addition to topics related to the 2013 PDC15 threat, papers are solicited in the areas listed below: Planetary Defense – Recent Progress & Plans • Current national and international funded activities that support planetary defense • Program status and plans (e.g., NASA’s NEO program, ESA and EU NEO & SSA program) • Recently conducted NEO threat simulation and disaster mitigation exercises NEO Discovery • Overviews of current ground and space-based discovery statistics • Current discovery and follow-up capabilities, and advances in utilizing archival data • Orbital refinements including non-gravitational effects and keyholes • New surveys expected to be operational -

In the Castelli Romani Area

The team Daniela Da Milano Professional journalist, she has worked with various newspapers, published tourist guides and has over twenty years’ experience in Editorial Design, Events Management and Advertising Campaigns. Corinna Lucarini Professor of Humanities at the high school Joyce, Ariccia, she has been a curator of routes of itineraries of Responsible Tourism in the Mediterranean Area, for FAI (Italian Environment Fund) and local associations. The disclosure is the cultural centre of her professional and personal interests, believing in the possibility of combining real economy, environmental protection, culture and ethics. Federica Nobilio Heritage promoter and tour guide in French. She is an expert in identifying sites, goods, products related to traditions, in conceiving and designing the promotional actions of the the area and the activities of distribution and marketing. Gianna Petrucci Graphic visualizer, she has to her credit several collaborations including private companies, government departments, Natural History Museums, Local Authorities. She is currently working to heal the national leaders of the Gambero Rosso. She loves her land and for years has been investing her energies in promoting and enhancing the Castelli Romani’s strengths. Jessica Proietti Degree in Art History at the University La Sapienza of Rome, she earned a master’s degree in Development and Management of Historic Centres Children at the same University. She collaborated in the preparation of the Strategic Framework Valuation on behalf of the Umbria -

ROME, LAZIO CITIES and SEA 2020 Rotary Club Guidonia Montecelio Invite Young People to the Beautiful Cities Near Rome for an International Cultural Camp

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 2080 YOUTH EXCHANGE PROGRAM ROME, LAZIO CITIES AND SEA 2020 Rotary Club Guidonia Montecelio invite young people to the beautiful cities near Rome for an International Cultural Camp 10 July -19 July 2020 Program: Culture, history, heritage, sea and fun around, in and beyond Rome. Participants: 8 students One Girl or One Boy ONLY per country will be accepted Age 18/22 years old at the time of the camp Language English Accommodation Hosting Families. Camp Fee 350 Euro. Acceptance & Payment Students will be accepted provisionally on receipt of a scanned application form on a first come first served basis. Once students have been accepted provisionally according to a gender balancing rule, we’ll communicate them details about payment’s preferred method. Payment secures the confirmation Cancellation: In case of accepted students that communicate their cancellation within May 31 2020, the fee will be refunded completely. After this date nothing will be refunded. So, we recommend everyone to get special cancellation insurance. Additional Costs: Participants have to provide individually to travel to and from Rome; we suggest to bring a reasonable amount of pocket money or credit cards for any cost in Italy. Insurance: All participants are responsible for insuring themselves according to the guidelines in Rotary International Code of Policies on Travel insurance for Students, which covers illness, accident, third party damages and personal effects. Details will be sent to successful applicants with their Joining instructions in May. European participants should bring their European Health Insurance Card. Clothes: Casual clothes. TRAVEL ARRANGEMENTS Arrival 10 July 2020 Airport: Rome Fiumicino – Rome Ciampino Train (Eurostar): Roma Termini Station- Roma Tiburtina Station Rotary Club Representatives will be ONLY at Rome Fiumicino airport, Rome Ciampino airport or Rome Termini railway Station, Tiburtina railway station to provide assistance and transportation (arrival and departure). -

Il “Caso Ardea”

IL CAFFÈ NON RICEVE CONTRIBUTI PUBBLICI PER L'EDITORIA di POMEZIA-ARDEA n. 307 - dal 12 al 25 febbraio 2015 - tel. 06.92.76.222 - [email protected] - GRATUITO ARDEA Il Comandante dei Il “caso Ardea” finisce in Parlamento carabinieri in pensione Un deputato leghista interroga Alfano: “Il Sindaco Di Fiori sminuisce il problema” Lgt. Antonio Una scia lunghissima di attentati quella che si regi- Alfano. Per il parlamentare, nell’audizione nella com- Landi stra da mesi ad Ardea, senza che le indagini sinora missione impegnata sulle intimidazioni subite dagli abbiano portato a qualche soluzione. Una vera piaga, amministratori pubblici, il sindaco Luca Di Fiori in un territorio assediato dalle mafie. A sollevare il avrebbe sminuito il problema. Grimoldi ha così chie- caso in Parlamento è il deputato leghista Paolo Gri- sto ad Alfano di intervenire, fronteggiando “l’emer- moldi, con un’interrogazione al ministro dell’Interno genza criminale in atto ad Ardea e sul litorale laziale”. a pag. 6 Antonio Landi è stato per anni il SALZARE, GIÙ ALTRI 10 APPARTAMENTI ABUSIVI punto di riferimento di Ardea Abbandono di rifiuti, a pag. 25 fioccano le multe ARDEA Pomezia, telecamere contro gli incivili Nuova ordinanza a pag. 18 contro la prostituzione Le sanzioni scendono a 300 euro. Sarà in vigore fino al 10 agosto Una scuola migliore a pag. 37 POMEZIA Al Teatro Vittoria i giovani di Lazio InScena Pascal e Copernico uniti nella protesta Va avanti la guerra al degrado e all’abusivismo. Sempre più difficile la convivenza tra gli occupanti e i regolari. Il sogno del Sindaco: «Costruire lì una cittadella della legalità» a pag. -

Elenco Codici Uffici Territoriali Dell'agenzia Delle Entrate

ROMA Le funzioni operative dell'Agenzia delle Entrate sono svolte dalle: • Direzione Provinciale I di ROMA articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di ROMA 1 - TRASTEVERE , ROMA 2 - AURELIO , ROMA 3 - SETTEBAGNI • Direzione Provinciale II di ROMA articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di ROMA 5 - TUSCOLANO , ROMA 6 - EUR TORRINO , ROMA 7 - ACILIA , POMEZIA • Direzione Provinciale III di ROMA articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di ROMA 4 - COLLATINO , ALBANO LAZIALE , TIVOLI , FRASCATI , PALESTRINA , VELLETRI Direzione Provinciale I di ROMA Sede Comune: ROMA Indirizzo: VIA IPPOLITO NIEVO 36 CAP: 00153 Telefono: 06/583191 Fax: 06/50763637 E-mail: [email protected] PEC: [email protected] TK2 Municipi di Roma : I, III, XII, XIII, XIV, XV. Comuni : Anguillara Sabazia, Bracciano, Campagnano di Roma, Canale Monterano, Capena, Castelnuovo di Porto, Civitella San Paolo, Fiano Romano, Filacciano, Fonte Nuova, Formello, Magliano Romano, Manziana, Mazzano Romano, Mentana, Monterotondo, Morlupo, Nazzano, Ponzano Romano, Riano, Rignano Flaminio, Sacrofano, Sant'Oreste, Torrita Tiberina, Trevignano Romano. Comune: ROMA Indirizzo: VIA IPPOLITO NIEVO 36 CAP: 00153 Telefono: 06/583191 Fax: 06/50763636 E-mail: [email protected] TK3 Indirizzo: VIA IPPOLITO NIEVO 36 CAP: 00153 Telefono: 06/583191 Fax: 06/50763635 E-mail: [email protected] TK3 Mappa della Direzione Provinciale I di -

Elenco Corsisti Plenaria - Cerveteri - E

SCUOLA POLO I.C.CENA - ELENCO CORSISTI PLENARIA - CERVETERI - E. MATTEI Sede di servizio Cognome Nome 2 CERVETERI ALEO FILIPPA 3 MANZIANA ALUNNI ELISABETTA 4 LADISPOLI AMATO SABRINA 5 LADISPOLI AMICI SIMONA 6 BRACCIANO ANTOGNONI GABRIELE 7 LADISPOLI ANTONELLI PATRIZIA 8 LADISPOLI ARTUSI DANIELA 9 LADISPOLI AUTOLITANO ANNA MARIA 10 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA AVELLINO MICHELINA 11 LADISPOLI BALDINI FRANCESCA 12 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA BALSAMO VENERANDA 13 CERVETERI BANDIERA TIZIANA 14 LADISPOLI BAORTO MARIKA 15 LADISPOLI BARIOLI RENATO 16 LADISPOLI BARLAFANTE VALERIA 17 BRACCIANO BASSANELLI EMANUELE 18 LADISPOLI BERNARDI DANIELA 19 LADISPOLI BERTOLLI DOMENICO AMLETO 20 LADISPOLI BLASI LAURA 21 BRACCIANO BOCCHINI BRUNO 22 LADISPOLI BOMARSI FRANCESCA 23 LADISPOLI BONACCI CHIARA 24 LADISPOLI BONANNO MARIA 25 TREVIGNANO ROMANO BOTTINI ROSSELLA 26 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA BRACCI FRANCESCO 27 LADISPOLI BREGAMO LUCIA ELENA MARIA 28 BRACCIANO BUCCIARELLI SILVIA 29 LADISPOLI BUCCIERO LAURA 30 LADISPOLI CADONI MARIA GRAZIA 31 LADISPOLI CALATO BRUNA 32 CERVETERI CALZECCHI ONESTI STEFANO 33 BRACCIANO CAMELE PAOLA 34 LADISPOLI CAMPANELLA DORIANA 35 LADISPOLI CANDELORI STEFANIA 36 BRACCIANO CANGIAMILA SALVATORE 37 BRACCIANO CAPALOZZA GIADA 38 LADISPOLI CAPODACQUA ANNA 39 CERVETERI CAPONE GIOVANNA 40 CERVETERI CAPORALE ALESSIA 41 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA CAPUANO VITA MARIA 42 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA CARISSIMI FRANCESCA 43 ANGUILLARA SABAZIA CAROSI CRISTINA 44 BRACCIANO CAROTENUTO GAETANA 45 BRACCIANO CATARINOZZI LOREDANA 46 CERVETERI CATERINA MARCELLA 47 BRACCIANO CATINI DANIELE 48 -

Rmee000vs8 Provincia Di Roma

Nel presente documenti sono contenuti i codici di tutte le scuole del territorio dei Castelli Romani. Ai fini della corretta compilazione delle iscrizioni, si suggerisce di controllare i codici delle scuole scelte in caso di non accoglimento della domanda verificando presso le istituzioni interessate. A - DISTRETTO 037 RMCT71300V CENTRO TERRITORIALE PERMANENTE - ISTRUZIONE IN ETA' ADULTA FRASCATI - VIA RISORGIMENTO, 3 (NON ESPRIMIBILE DAL PERSONALE DIRIGENTE SCOLASTICO) CON SEDE AMMINISTRATIVA IN FRASCATI : RMIC8DE00D DISTRETTI DI COMPETENZA : 037 RMEEC900W9 COMUNE DI COLONNA RMEE8AA01C COLONNA - TIBERIO GULLUNI (ASSOC. I. C. RMIC8AA00A) VIA CAPOCROCE, 4 COLONNA (SEDE DI ORGANICO - ESPRIMIBILE DAL PERSONALE DOCENTE) RMIC8AA00A ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO TIBERIO GULLUNI COLONNA - VIA CAPOCROCE, 4 (ESPRIMIBILE DAL PERSONALE A.T.A. E DIRIGENTE SCOLASTICO) CON SEZIONI ASSOCIATE : RMAA8AA006 - COLONNA, RMAA8AA017 - COLONNA, RMEE8AA01C - COLONNA, RMMM8AA01B - COLONNA RMEED773X7 COMUNE DI FRASCATI RMEE8DE02L FRASCATI I ANNA M. LUPACCHINO (ASSOC. I. C. RMIC8DE00D) VIA DEI LATERENZI COCCIANO RMEE8DE03N FRASCATI I- ANDREA TUDISCO (ASSOC. I. C. RMIC8DE00D) VIA CISTERNOLE PANTANO SECCO RMEE8DE01G FRASCATI I- E. DANDINI (ASSOC. I. C. RMIC8DE00D) VIA RISORGIMENTO 1 (SEDE DI ORGANICO - ESPRIMIBILE DAL PERSONALE DOCENTE) RMEE8C302A FRASCATI II - VERMICINO (ASSOC. I. C. RMIC8C3007) VIA VANVITELLI VERMICINO-FRASCATI RMEE8C3019 FRASCATI II - VILLA SCIARRA (ASSOC. I. C. RMIC8C3007) VIA DON BOSCO, 8 FRASCATI (SEDE DI ORGANICO - ESPRIMIBILE DAL PERSONALE DOCENTE) RMIC8C3007 ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO I. C. FRASCATI II' FRASCATI - VIA DON BOSCO 8 (ESPRIMIBILE DAL PERSONALE A.T.A. E DIRIGENTE SCOLASTICO) CON SEZIONI ASSOCIATE : RMAA8C3003 - FRASCATI, RMAA8C3014 - FRASCATI, RMAA8C3025 - FRASCATI, RMAA8C3036 - FRASCATI, RMEE8C3019 - FRASCATI, RMEE8C302A - FRASCATI, RMMM8C3018 - FRASCATI RMIC8DE00D ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO IC FRASCATI I FRASCATI - VIA RISORGIMENTO, 3 (ESPRIMIBILE DAL PERSONALE A.T.A.