Secrets of the Deep: Defining Privacy Underwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebecca Farden Information Technology 101 Term Paper the US Military Uses Some of the Most Advanced Technologies Known to Man, O

Rebecca Farden Information Technology 101 Term Paper Use of Robotics in the US Military The US military uses some of the most advanced technologies known to man, one main segment being robotics. As this growing field of research is being developed, militaries around the world are beginning to use technologies that may change the way wars are fought. The trend we are currently seeing is an increase in unmanned weaponry, and decrease in actual human involvement in combat. Spending on research in this area is growing drastically and it is expected to continue. Thus far, robotics have been viewed as a positive development in their militaristic function, but as this field advances, growing concerns about their use and implications are arising. Currently, robotics in the military are used in a variety of ways, and new developments are constantly surfacing. For example, the military uses pilotless planes to do surveillance, and unmanned aerial attacks called “drone” strikes (Hodge). These attacks have been frequently used in Iraq in Pakistan in the past several years. Robotics have already proved to be very useful in other roles as well. Deputy commanding general of the Army Maneuver Support Center Rebecca Johnson said “robots are useful for chemical detection and destruction; mine clearing, military police applications and intelligence” (Farrell). Robots that are controlled by soldiers allow for human control without risking a human life. BomBots are robots that are have been used in the middle east to detonate IEDs (improvised explosive devices), keeping soldiers out of this very dangerous situation (Atwater). These uses of robots have been significant advances in the way warfare is carried out, but we are only scratching the surface of the possibilities of robotics in military operations. -

AI, Robots, and Swarms: Issues, Questions, and Recommended Studies

AI, Robots, and Swarms Issues, Questions, and Recommended Studies Andrew Ilachinski January 2017 Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Distribution Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the Defense Technical Information Center at www.dtic.mil or contact CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Photography Credits: http://www.darpa.mil/DDM_Gallery/Small_Gremlins_Web.jpg; http://4810-presscdn-0-38.pagely.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ Robotics.jpg; http://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-edia/image/upload/18kxb5jw3e01ujpg.jpg Approved by: January 2017 Dr. David A. Broyles Special Activities and Innovation Operations Evaluation Group Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract The military is on the cusp of a major technological revolution, in which warfare is conducted by unmanned and increasingly autonomous weapon systems. However, unlike the last “sea change,” during the Cold War, when advanced technologies were developed primarily by the Department of Defense (DoD), the key technology enablers today are being developed mostly in the commercial world. This study looks at the state-of-the-art of AI, machine-learning, and robot technologies, and their potential future military implications for autonomous (and semi-autonomous) weapon systems. While no one can predict how AI will evolve or predict its impact on the development of military autonomous systems, it is possible to anticipate many of the conceptual, technical, and operational challenges that DoD will face as it increasingly turns to AI-based technologies. -

599-0782, [email protected] FACT SHEET Famil

CONTACT: Cara Schneider (215) 599-0789, [email protected] Donna Schorr (215) 599-0782, [email protected] FACT SHEET Family Fun In Philadelphia Historic District: Attractions: The African American Museum in Philadelphia – Now in its 40th year, this groundbreaking museum takes a fresh and bold look at the stories of African-Americans and their role in the founding of the nation through the core exhibit Audacious Freedom. Children’s Corner, an interactive installment for ages three through eight, lets kids explore the daily lives of youth in Philadelphia from 1776-1876. Other exhibits examine contemporary issues through art and historic artifacts. Weekend family workshops and special events take place throughout the year. 701 Arch Street, (215) 574-0380, aampmuseum.org Betsy Ross House – America’s most famous flag maker greets guests in her interactive 18th- century upholstery shop. Visitors learn about Betsy’s life and legend from the lady herself and Phillis, an African-American colonial who explains and shows what life was like for a freed black woman in the 18th century. An audio tour caters to four-to-eight-year-olds, offering lessons in Colonial life and the opportunity to solve “history mysteries.” 239 Arch Street, (215) 629-4026, betsyrosshouse.org Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia – Everyone handles money, but how does it arrive in people’s wallets? The Federal Reserve’s hands-on Money in Motion exhibit at explains it all. Plus, games invite visitors to “Match Wits with Ben,” and an impressive collection of old and rare currency is on display. 6th & Arch Streets, (866) 574-3727, (215) 574-6000, philadelphiafed.org Fireman’s Hall Museum – Future emergency responders get a head start at this restored 1902 firehouse, home to some of the nation’s earliest firefighting equipment, including hand, steam and motor fire engines, as well as a 9/11 exhibit and an interactive kiosk that teaches kids about 9-1-1 services. -

Responsibility Practices in Robotic Warfare Deborah G

Responsibility Practices in Robotic Warfare Deborah G. Johnson, Ph.D., and Merel E. Noorman, Ph.D. NMANNED AERIAL VEHICLES (UAVs), also known as drones, are commonplace in U.S. military operations. Many predict increased military use of more sophisti- Ucated and more autonomous robots.1 Increased use of robots has the potential to transform how those directly involved in warfare, as well as the public, perceive and experience war. Military robots allow operators and commanders to be miles away from the battle, engag- ing in conflicts virtually through computer screens and controls. Video cameras and sen- sors operated by robots provide technologically mediated renderings of what is happening on the ground, affecting the actions and attitudes of all involved. Central to the ethical concerns raised by robotic warfare, especially the use of autonomous military robots, are issues of responsibility and accountability. Who will be responsible when robots decide for themselves and behave in unpredictable ways or in ways that their human partners do not understand? For example, who will be responsible if an autonomously operating unmanned aircraft crosses a border without authorization or erroneously identifies a friendly aircraft as a target and shoots it down?2 Will a day come when robots themselves are considered responsible for their actions?3 Deborah G. Johnson is the Anne Shirley Carter Olsson Professor of Applied Ethics in the Science, Technology, and Society Program at the University of Virginia. She holds a Ph.D., M.A., and M.Phil. from the University of Kansas and a B.Ph. from Wayne State University. The author/editor of seven books, she writes and teaches about the ethical issues in science and engineering, especially those involving computers and information technology. -

2021 Summer Camps

COVER SUMMER CAMPS 2021 Look Inside ... then get outside Funshine Summer Camp • Corbin Art Center Outdoor adventure camps • Day camps at merkel All Spokane Parks and Recreation programs are offered in accordance with current COVID-19 guidelines. Summer is just around the corner! In these challenging times of COVID-19, we hope that Parks & Recreation can be a place to support your mental and physical health. In-person programs are modified in accordance with the Spokane Regional Health District, following the Governor’s mandates for the current phase guidelines. Decreased capacity, mask wearing, physical distancing, and frequent sanitation are just a few of the measures in place. Our top priority is to meet the health and safety needs of our participants, campers and staff, and provide a positive and fun experience for all, in accordance with the specific guidance for operations. Here are a few important dates and details to help you plan: • This guide is for summer camps only. The full Summer Activity Guide that features activities beyond camps will be posted online and mailed out in May 2021. • Most summer camps you see in this guide will start their first session the week of June 21. • The Aquatics 2021 season schedules will come out in the complete Summer Activity Guide. However, the schedule may be available online earlier, at SpokaneRec.org under the Aquatics tab. Swim lesson registration will open May 1. • Witter Aquatics Center is anticipated to open for Pre-Season lap swim on Monday, May 10, 2021. Pre-registration will be required as part of our COVID protocols through SpokaneRec.org, under the Aquatics tab. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Wednesday, March 18, 2009 2:36:33PM School: Churchland Academy Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 36573 EN Big Egg Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 9329 EN Oh No, Otis! Frankel, Julie LG 0.4 0.5 97 F 9333 EN Pet for Pat, A Snow, Pegeen LG 0.4 0.5 71 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 9305 EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Stevens, Philippa LG 0.5 0.5 100 F 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet LG 0.5 0.5 144 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 196 F 7282 EN Lucky Bear Phillips, Joan LG 0.5 0.5 150 F 31542 EN Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby LG 0.5 0.5 106 F 901618 EN Night Watch (SF Edition) Fear, Sharon LG 0.5 0.5 51 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 74854 EN Cooking with the Cat Worth, Bonnie LG 0.6 0.5 135 F 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans LG 0.6 0.5 74 F 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. -

Groovy Movie Music

TASK TIME ONLINE GROOVY MOVIE MUSIC ACTIVITY 1 What Movie is that song from? There are some songs that when you hear them, you immediately think of a movie. Your task is to match the song and the artist with the movie it is associated with. SONG TITLE ( ARTIST) MOVIE TITLE A Whole New World ( Peabo Bryson/ Regina Belle) Bare Necessities (Phil Harris) The Lion King Beyond the Sea (Robbie Williams) The Wizard of Oz Circle of Life (Elton John) The Muppet Movie Colours of the Wind (Pocahontas) The Little Mermaid Down to Earth (Peter Gabriel) The Jungle Book Hallelujah (Rufus Wainwright) Aladdin I like to Move It, Move It (Reel2Real) Toy Story I See the Light (Mandy Moore/Zachary Levi) Shrek Pocahontas If I didn’t Have You (Billy Crystal/John Goodman) Mary Poppins Le Festin (Camille) Cars Life is a Highway (Rascal Flatts) How to Train Your Dragon Over the Rainbow (Judy Garland) Tarzan Rainbow Connection (Kermit) WALL.E Reflection (Lea Salonga) Monsters Inc. Sticks and Stones (Jonsi) Finding Nemo Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious (Julie Andrews) Ratatouille Under the Sea (Samuel E Wright) Mulan You’ll Bi In My Heart (Phil Collins) Tangled You’ve Got a Friend In Me (Randy Newman) Madagascar ACTIVITY 2 YOUR FAVOURITE? There are thousands of songs from movies but what are the best? It is very difficult to pick the top ten from so many. Listen to the short grabs of the 25 theme songs from different films. Rate them in order from your favourite (1) to least favourite (25). Add two other movies whose music you highly rate. -

The Arms Industry and Increasingly Autonomous Weapons

Slippery Slope The arms industry and increasingly autonomous weapons www.paxforpeace.nl Reprogramming War This report is part of a PAX research project on the development of lethal autonomous weapons. These weapons, which would be able to kill people without any direct human involvement, are highly controversial. Many experts warn that they would violate fundamental legal and ethical principles and would be a destabilising threat to international peace and security. In a series of four reports, PAX analyses the actors that could potentially be involved in the development of these weapons. Each report looks at a different group of actors, namely states, the tech sector, the arms industry, and universities and research institutes. The present report focuses on the arms industry. Its goal is to inform the ongoing debate with facts about current developments within the defence sector. It is the responsibility of companies to be mindful of the potential applications of certain new technologies and the possible negative effects when applied to weapon systems. They must also clearly articulate where they draw the line to ensure that humans keep control over the use of force by weapon systems. If you have any questions regarding this project, please contact Daan Kayser ([email protected]). Colophon November 2019 ISBN: 978-94-92487-46-9 NUR: 689 PAX/2019/14 Author: Frank Slijper Thanks to: Alice Beck, Maaike Beenes and Daan Kayser Cover illustration: Kran Kanthawong Graphic design: Het IJzeren Gordijn © PAX This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (CC BY 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/deed.en We encourage people to share this information widely and ask that it be correctly cited when shared. -

Boston Dynamics from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Boston Dynamics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Boston Dynamics is an engineering and robotics Boston Dynamics design company that is best Industry Robotics known for the development Headquarters Waltham, Massachusetts, United of BigDog, a quadruped States robot designed for the U.S. military with funding from Owner Google Defense Advanced Research Parent Google Projects Agency Website www.bostondynamics.com [1][2] (DARPA), and DI-Guy, (http://www.bostondynamics.com/) software for realistic human simulation. Early in the company's history, it worked with the American Systems Corporation under a contract from the Naval Air Warfare Center Training Systems Division (NAWCTSD) to replace naval training videos for aircraft launch operations with interactive 3D computer simulations featuring DI-Guy characters.[3] Marc Raibert is the company's president and project manager. He spun the company off from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1992.[4] On 13 December 2013, the company was acquired by Google, where it will be managed by Andy Rubin.[5] Immediately before the acquisition, Boston Dynamics transferred their DI-Guy software product line to VT MÄK, a simulation software vendor based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[6] Contents 1 Products 1.1 BigDog 1.2 Cheetah 1.3 LittleDog 1.4 RiSE 1.5 SandFlea 1.6 PETMAN 1.7 LS3 1.8 Atlas 1.9 RHex 2 References 3 External links Products BigDog BigDog is a quadrupedal robot created in 2005 by Boston Dynamics, in conjunction with Foster-Miller, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Harvard University Concord Field Station.[7] It is funded by the DARPA[8] in the hopes that it will be able to serve as a robotic pack mule to accompany soldiers in terrain too rough for vehicles. -

Popular Selection List, 2015 Edition

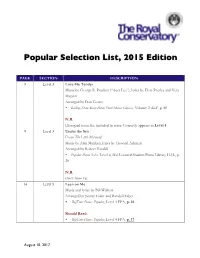

Popular Selection List, 2015 Edition PAGE SECTION DESCRIPTION 9 Level 3 Love Me Tender Music by George R. Poulton (“Aura Lee”); lyrics by Elvis Presley and Vera Matson Arranged by Dan Coates Rolling Stone Easy Piano Sheet Music Classics, Volume 2 ALF, p. 80 N.B. Disregard from list, included in error: Correctly appears in Level 4 9 Level 3 Under the Sea From The Little Mermaid Music by Alan Menken; lyrics by Howard Ashman Arranged by Robert Vandall Popular Piano Solos, Level 4, Hal Leonard Student Piano Library HAL, p. 26 N.B. Omit from list. 14 Level 5 Lean on Me Music and lyrics by Bill Withers Arranged by Nancy Faber and Randall Faber BigTime Piano: Popular, Level 4 FPA, p. 16 Should Read: BigTime Piano: Popular, Level 4 FPA, p. 17 August 10, 2017 18 Level 7 The Story of Us Music and lyrics by Taylor Swift • Taylor Swift for Piano Solo HAL, p. 7 Should Read: • Taylor Swift for Piano Solo HAL, p. 68 20 Level 8 Chasing Pavements Music and lyrics by Adele Adkins and Francis “Eg” White Adele for Piano Solo HAL, p. 3 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. 8 21 Level 8 Make You Feel My Love Music and lyrics by Bob Dylan Adele for Piano Solo HAL, p. 12 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. 21 21 Level 8 Puttin’ on the Ritz Music and lyrics by Irving Berlin Arranged by Jeremy Siskind The Magic of Standards HAL, p. -

Underwater Music: Tuning Composition to the Sounds of Science

OUP UNCORRECTED FIRST-PROOF 7/6/11 CENVEO chapter 6 UNDERWATER MUSIC: TUNING COMPOSITION TO THE SOUNDS OF SCIENCE stefan helmreich Introduction How should we apprehend sounds subaqueous and submarine? As humans, our access to underwater sonic realms is modulated by means fl eshy and technological. Bones, endolymph fl uid, cilia, hydrophones, and sonar equipment are just a few apparatuses that bring watery sounds into human audio worlds. As this list sug- gests, the media through which humans hear sound under water can reach from the scale of the singular biological body up through the socially distributed and techno- logically tuned-in community. For the social scale, which is peopled by submari- ners, physical oceanographers, marine biologists, and others, the underwater world —and the undersea world in particular — often emerge as a “fi eld” (a wildish, distributed space for investigation) and occasionally as a “lab” (a contained place for controlled experiments). In this chapter I investigate the ways the underwater realm manifests as such a scientifi cally, technologically, and epistemologically apprehensible zone. I do so by auditing underwater music, a genre of twentieth- and twenty-fi rst-century 006-Pinch-06.indd6-Pinch-06.indd 115151 77/6/2011/6/2011 55:06:52:06:52 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED FIRST-PROOF 7/6/11 CENVEO 152 the oxford handbook of sound studies composition performed or recorded under water in settings ranging from swim- ming pools to the ocean, with playback unfolding above water or beneath. Composers of underwater music are especially curious about scientifi c accounts of how sound behaves in water and eager to acquire technologies of subaqueous sound production. -

Music Express Song Index V1-V17

John Jacobson's MUSIC EXPRESS Song Index by Title Volumes 1-17 Song Title Contributor Vol. No. Series Theme/Style 1812 Overture (Finale) Tchaikovsky 15 6 Luigi's Listening Lab Listening, Classical 5 Browns, The Brad Shank 6 4 Spotlight Musician A la Puerta del Cielo Spanish Folk Song 7 3 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A la Rueda de San Miguel Mexican Folk Song, John Higgins 1 6 Corner of the World World Music A Night to Remember Cristi Cary Miller 7 2 Sound Stories Listening, Classroom Instruments A Pares y Nones Traditional Mexican Children's Singing Game, arr. 17 6 Let the Games Begin Game, Mexican Folk Song, Spanish A Qua Qua Jerusalem Children's Game 11 6 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A-Tisket A-Tasket Rollo Dilworth 16 6 Music of Our Roots Folk Songs A-Tisket, A-Tasket Folk Song, Tom Anderson 6 4 BoomWhack Attack Boomwhackers, Folk Songs, Classroom A-Tisket, A-Tasket / A Basketful of Fun Mary Donnelly, George L.O. Strid 11 1 Folk Song Partners Folk Songs Aaron Copland, Chapter 1, IWMA John Jacobson 8 1 I Write the Music in America Composer, Classical Ach, du Lieber Augustin Austrian Folk Song, John Higgins 7 2 It's a Musical World! World Music Add and Subtract, That's a Fact! John Jacobson, Janet Day 8 5 K24U Primary Grades, Cross-Curricular Adios Muchachos John Jacobson, John Higgins 13 1 Musical Planet World Music Aeyaya balano sakkad M.B. Srinivasan. Smt. Chandra B, John Higgins 1 2 Corner of the World World Music Africa: Music and More! Brad Shank 4 4 Music of Our World World Music, Article African Ancestors: Instruments from Latin Brad Shank 3 4 Spotlight World Music, Instruments Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 8 4 Listening Map Listening, Classical, Composer Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 1 4 Listening Map Listening, Composer Ah! Si Mon Moine Voulait Danser! French-Canadian Folk Song, John Jacobson, John 13 3 Musical Planet World Music Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around African-American Folk Song, arr.