Videotape Transfer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sony Recorder

Sony Recorder www.ctlny.com 24 All prices subject to change DVCAM, J-Series, Portable & Betacam Recorders DVCAM Recorders J-Series Betacam Recorders SP Betacam Recorders Sony Model# DSR1500A Sony Model# J1/901 Sony Model# PVW2600 Sales price $5,680.08 Sales price $5,735.80 Sales price $12,183.36 Editing recorder also play Beta/SP/SX Player w/ Betacam SP Video Editing DVCPRO,SDI-YUV Component Output Player with TBC & TC optional 8-3/8 x 5-1/8 x 16-5/8 16-7/8 x 7-5/8 x 19-3/8 Model # List Sales price Model # List Sales price Model # List Sales price DSR1500A $7,245.00 $5,680.08 J1/901 $6,025.00 $5,735.80 PVW2600 $15,540.00 $12,183.3 Editing recorder also play DVCPRO,SDI-YUV optional Beta/SP/SX Player w/ Component Output Betacam SP Video Editing Player with TBC & TC 6 DSR1600 $6,975.00 $5,468.40 J1/902 $7,050.00 $6,711.60 PVW2650 $22,089.00 $17,317.7 Edit Player w/ DVCPRO playback, RS-422 & DV Output Beta/SP/SX Editing Player w/ SDI Output Betacam SP Editing Player w. Dynamic Tracking, TBC & TC8 DSR1800 $9,970.00 $7,816.48 J2/901 $10,175.00 $9,686.60 PVW2800 $23,199.00 $18,188.0 Edit Recorder w/DVCPRO playback,RS422 & DV Output IMX/SP/SX Editing Player w/ Component Output Betacam SP Video Editing Recorder with TBC & TC 2 DSR2000 $15,750.00 $13,229.4 J2/902 $11,400.00 $10,852.8 UVW1200 $6,634.00 $5,572.56 DVCAM/DVCPRO Recorder w/Motion Control,SDI/RS422 4 IMX/SP/SX Editing Player w/ SDI Output 0 Betacam Player w/ RGB & Auto Repeat Function DSR2000P $1,770.00 $14,868.0 J3/901 $12,400.00 $11,804.8 UVW1400A $8,988.00 $7,549.92 PAL DVCAM/DVCPRO -

Order on Reconsideration and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Federal Communications Commission FCC 13-84 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Closed Captioning of Internet Protocol-Delivered ) MB Docket No. 11-154 Video Programming: Implementation of the ) Twenty-First Century Communications and Video ) Accessibility Act of 2010 ) ORDER ON RECONSIDERATION AND FURTHER NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING Adopted: June 13, 2013 Released: June 14, 2013 Comment Date: (60 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) Reply Comment Date: (90 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) By the Commission: Commissioner Pai approving in part, concurring in part and issuing a statement. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 2 II. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................................... 3 III. ORDER ON RECONSIDERATION ..................................................................................................... 5 A. Petition for Reconsideration of the Consumer Electronics Association .......................................... 5 1. Scope of the Apparatus Closed Captioning Rules..................................................................... 5 2. Application of the Apparatus Rules to Removable Media Players ......................................... 16 3. Application of the January 1, 2014 Deadline Only -

Sony Recognises That Your Needs As a Programme Maker Will Vary Depending Upon the Type of Pro- HDCAM Uses Intra-Frame DCT Compression Using a Gramme Being Made

HDW-M2000P/20 HDCAM video tape recorder with CineAlta record feature and multi-format playback A high definition VTR for prestige and mainstream Features programme production HDCAM recording and playback Sony recognises that your needs as a programme maker will vary depending upon the type of pro- HDCAM uses intra-frame DCT compression using a gramme being made. This has driven the develop- compression ratio of about 7:1. There are four chan- ment of a multi-format high definition product offer- nels of 48kHz digital audio at 20-bit resolution. ing, including HDV for entry-level high definition oper- ation, HDCAM for mainstream and prestige produc- Selectable frame rates tions, CineAlta for 24P applications, and HDCAM SR The HDW-M2000P/20 can record and replay at 1080/ for productions where only the ultimate quality will 50i, 1080/59.94i, 1080/25P, 1080/29.97P, 1080/ suffice. 23.98P and 1080/24P. HDCAM has long been associated with the production Compatible replay of standard definition cassettes of the most prestigious movies, commercials and tele- Betacam, Betacam SP, Betacam SX, MPEG IMX and vision programmes. The recent expansion of the Digital Betacam cassettes can be replayed. The HDW- HDCAM product line up has transformed the econom- M2000P/20 is optimised for analogue 625/50 Betacam ics of HD for mainstream television production, with and Betacam SP playback, but can replay 525/60 new models such as the HDW-730S camcorder mak- Betacam and Betacam SP tapes and provide a monit- ing HD acquistion accessible to those working on oring quality output. -

Will Sonyâ•Žs Fourth Playstation Lead to a Second Sony V. Universal?

WILL SONY’S FOURTH PLAYSTATION LEAD TO A SECOND SONY V. UNIVERSAL? † SETH ASCHER ABSTRACT Sony has included a “share” button on the next version of their popular PlayStation video game system. This feature is meant to allow players to record and share videos of their gameplay. This service shares similarities with the controversial “record” button that Sony included with its Betamax players over thirty years ago. The Betamax player was the subject of the landmark case Sony v. Universal, a foundational case for the modern application of copyright law to new technology. This Issue Brief examines how this “share” feature would fare under the framework laid out by Sony v. Universal and other evolutions in copyright law. INTRODUCTION On February 20, 2013, Sony announced their newest videogame system, predictably named the PlayStation 4.1 Chief among its new features is the share button displayed prominently on its controller.2 Microsoft’s newest offering also has a similar feature.3 Pressing the share button will allow a player to post images or videos of their gameplay to the internet, sharing them with their friends and complete strangers.4 The PlayStation 4 even buffers the last few minutes of gameplay so that a player can share their gameplay video after the fact.5 Sony’s intention is to provide an easy way for players to share images and videos online. Copyright © 2014 by Seth Ascher. † Duke University School of Law, J.D. 2014. 1 Video of the press announcement is available on numerous websites. E.g., Sony PlayStation 4 Press Conference, GAMESPOT (Feb. -

A Comparison of the US Supreme Court's <I

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2006 Inducers and Authorisers: A Comparison of the US Supreme Court's Grokster Decision and the Australian Federal Court's KaZaa Ruling Jane C. Ginsburg Columbia Law School, [email protected] Sam Ricketson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Jane C. Ginsburg & Sam Ricketson, Inducers and Authorisers: A Comparison of the US Supreme Court's Grokster Decision and the Australian Federal Court's KaZaa Ruling, MEDIA & ARTS LAW REVIEW, VOL. 11, P. 1, 2006; U OF MELBOURNE LEGAL STUDIES RESEARCH PAPER NO. 144; COLUMBIA PUBLIC LAW RESEARCH PAPER NO. 06-105 (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/1401 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MELBOURNE LAW SCHOOL Legal Studies Research Paper Studies Paper No. 144 And COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series Paper No. 06-105 Inducers and Authorisers: A Comparison of the US Supreme Court’s Grokster Decision and the Australian Federal Court’s KaZaa Ruling PROFESSOR JANE GINSBURG COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL -And- PROFESSOR SAM RICKETSON UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Library at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=888928. -

DV-983H 1080P Up-Converting Universal DVD Player with VRS by Anchor Bay Video Processing and 7.1CH Audio

DV-983H 1080p Up-Converting Universal DVD Player with VRS by Anchor Bay Video Processing and 7.1CH Audio DV-983H is the new flagship model in OPPO's line of award-winning up-converting DVD players. Featuring Anchor Bay's leading video processing technologies, 7.1-channel audio, and 1080p HDMI up-conversion, the DV-983H Universal DVD Player delivers the breath-taking audio and video performance needed to make standard DVDs look their best on today's large screen, high resolution displays. The DV-983H provides a rich array of features for serious home theater enthusiasts. By applying source-adaptive, motion-adaptive, and edge-adaptive techniques, the DV-983H produces an outstanding image for any DVD, whether it’s mastered from an original theatrical release film or from a TV series. Aspect ratio conversion and multi-level zooming enable users to take full control of the viewing experience – maintain the original aspect ratio, stretch to full screen, or crop the unsightly black borders. Special stretch modes make it possible to utilize the full resolution of ultra high-end projectors with anamorphic lens. For users with an international taste, the frame rate conversion feature converts PAL movies for NTSC output without any loss of resolution or tearing. Custom home theater installers will find the DV-983H easy to integrate into whole-house control systems, thanks to its RS-232 and IR IN/OUT control ports. To complete the home theatre experience, the DV-983H produces stunning sound quality. Its 7.1 channel audio with Dolby Digital Surround EX decoding offers more depth, spacious ambience, and sound localization. -

Understanding Digital Video

chapter1 Understanding Digital Video Are you ready to learn more about how digital video works? This chapter introduces you to the concept of digital video, the benefits of going digital, the different types of digital video cameras, the digital video workflow, and essential digital video terms. COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL What Is Digital Video? ........................................ 4 Understanding the Benefits of Going Digital ................................................6 Discover Digital Video Cameras .......................8 The Digital Video Workflow ............................10 Essential Digital Video Terms .........................12 What Is Digital Video? Digital video is a relatively inexpensive, high-quality video format that utilizes a digital video signal rather than an analog video signal. Consumers and professionals use digital video to create video for the Web and mobile devices, and even to create feature-length movies. Analog versus Digital Video Recording Media versus Format Analog video is variable data represented as The recording medium is essentially the physical electronic pulses. In digital video, the data is broken device on which the digital video is recorded, like down into a binary format as a series of ones and a tape or solid-state medium (a medium without zeros. A major weakness of analog recordings is that moving parts, such as flash memory). The format every time analog video is copied from tape to tape, refers to the way in which video and audio data is some of the data is lost and the image is degraded, coded and organized on the media. Three popular which is referred to as generation loss. Digital video examples of digital video formats are DV (Digital is less susceptible to deterioration when copied. -

Blu-Ray Disc™ HDD Recorder

sr1500-1250_sales_guide.qxd 10.1.27 7:40 PM Page 1 Glossary Blu-ray Disc™ HDD Recorder G1080i GHDMI (High-definition Multimedia Interface) (500GB HDD) In a single high-definition image, 1080 (1125) alternating scan lines pass every 1/60th (NTSC) Established in Dec. 2002, HDMI is an interface for digital electronic equipment that acts as the SR-HD1500 or 1/50th (PAL) of a second to create an interlace image. And because 1080i (1125i) more than connection standard between PCs and displays. It transmits uncompressed HD digital audio doubles the current scan lines of 480i (525i) found on television broadcasts, it helps to ensure and video signals on a single cable without distortion. The DVI interface was its predecessor, (250GB HDD) that details are much clearer, enabling the creation of more realistic and richer images. and HDMI has been enhanced for AV equipment by adding functions such as audio SR-HD1250 transmission capability, copy protection of digital content and other intellectual properties, as well as the ability to transfer color-variation information. GAVCHD (Advanced Video Codec High Definition) AVCHD is an acronym for Advanced Video Codec High Definition, and it is the format for HD GMPEG-2 (Moving Picture Experts Group 2) camcorders used to record and playback high-definition video images. AVCHD uses the MPEG-2 is a standard for efficient data compression and color video expansion that is widely H.264/MPEG-4 AVC compression format for video to enable highly efficient encoding, the Dolby used for media such as DVDs and satellite-based digital broadcastings. Digital (AC-3) format with LPCM option for audio, and MPEG-2-TS for multiplexing. -

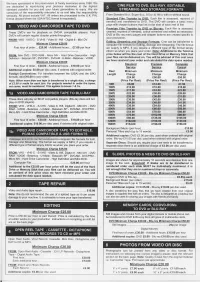

Minimum Charqe F25.00 Minimum Charqe €20.00

We have specialisedin the preservationof familymemories since 1988.We are dedicated to reproducing your precious memories to the highest standard possiblefor you and your future generationsto enjoy. We are consciousof the responsibilityentrusted to us and take this responsibility seriously.All prices includeVAT. All ordersare processedto the U.K. PAL FromStandard Bmm, Super Bmm, 9.5mm & 16mmwith or withoutsound. format(except where the USA NTSCformat is requested). Standard Film Transfer to DVD: Each film is assessed, repaired(if needed) and transferredto DVD. The DVD will contain a basic menu pagewith chaplerbuttons that link to the startof each reel of film. Premium Film Transfer to DVD or Blu-rav: Each film is assessed, These DVD's are for playback on DVD-R compatible players. Your cleaned,repaired (if needed),colour corrected and edited as necessary. DVD'swill containregular chapter points throughout. DVD or Blu-raymenu pages and chapterbuttons are createdspecific to your production. FROM:VHS -VHS-C - S-VHS-VideoB - HiB- DigitalB- MiniDV Editinq. Streaminq and Storaqe Formats: Cine can be transferredto MinimumCharqe €20.00 computerfile formatsfor Editing,Storage and Streaming.The file format Firsthour of order....€20.00 - Additionalhours.... €7.00 per hour we supply is MP4, if you require a differenttype of file format simply informus when you place your order. Note: Additional to the Telecine price below will be the the Hard Drive Memory FROM:Mini DVD - DVD RAM - MicroMV - Hard DriveCamcorder - High cost of or Stick that your Definition- BelacamSP - DVCPRO- DVCAM- U-Matic- Betamax- V2000. files can be delivered on. You will be advised of this cost once we have received your order and calculated the data space needed. -

Digital Video Quality Handbook (May 2013

Digital Video Quality Handbook May 2013 This page intentionally left blank. Executive Summary Under the direction of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T), First Responders Group (FRG), Office for Interoperability and Compatibility (OIC), the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL), worked with the Security Industry Association (including Steve Surfaro) and members of the Video Quality in Public Safety (VQiPS) Working Group to develop the May 2013 Video Quality Handbook. This document provides voluntary guidance for providing levels of video quality in public safety applications for network video surveillance. Several video surveillance use cases are presented to help illustrate how to relate video component and system performance to the intended application of video surveillance, while meeting the basic requirements of federal, state, tribal and local government authorities. Characteristics of video surveillance equipment are described in terms of how they may influence the design of video surveillance systems. In order for the video surveillance system to meet the needs of the user, the technology provider must consider the following factors that impact video quality: 1) Device categories; 2) Component and system performance level; 3) Verification of intended use; 4) Component and system performance specification; and 5) Best fit and link to use case(s). An appendix is also provided that presents content related to topics not covered in the original document (especially information related to video standards) and to update the material as needed to reflect innovation and changes in the video environment. The emphasis is on the implications of digital video data being exchanged across networks with large numbers of components or participants. -

10 Questions-Portable Disk Recorders

10 Questions : Portable Digital Disk Recorders 3/2011 1. Is the codec being captured to post-production friendly? Acquisition is the beginning of the work!ow and decisions made at this point in the process affect all that follows. For the easiest possible post-production work!ow, the footage would be immediately ready for editorial and would not require transcoding or intensive processing to make it ready for editing. The AJA Ki Pro and Ki Pro Mini record to the high quality Apple ProRes 422 codecs to produce full raster 10-bit 4:2:2 HD and SD #les ready for immediate edit. Apple ProRes 422 is supported in all of the Apple Final Cut Studio applications making it an ideal codec for ease of use in post-production. Perhaps most importantly, Apple ProRes codecs have been designed to handle the harsh rigors of Post production through rendering and effects cycles. Comparison 1440 x 1080 1920 x 1080 1280 x 1080 DVCPRO HD@50Hz Uncompressed HDCAM D5 DVCPRO HD@60Hz XDCAM HDCAM-SR HDV ProRes422 @145Mbps 1080 ProRes422 HQ HD @220Mbps 1280/1920 = 2/3 1440/1920 = 3/4 1920/1920 = 1/1 8 bit 8 bit 10 bit 10 Questions : Portable Digital Disk Recorders 3/2011 2. Is the storage module itself computer friendly ? Ki Pro offers removable spinning disk or SSD modules with FireWire 800 support for direct connection to an Apple Mac Pro or MacBook Pro. Ki Pro formats its media as OSX-native HFS+, so that the Storage Module will mount instantly on your Mac desktop as easily as any other Mac-formatted drive would. -

Paramount Theatre Sherry Lansing Theatre Screening Room #5 Marathon Theatre Gower Theatre

PARAMOUNT THEATRE SHERRY LANSING THEATRE SCREENING ROOM #5 MARATHON THEATRE GOWER THEATRE ith rooms that seat from 33 to 516 people, The Studios at Paramount has a screening room to accommodate an intimate screening with your production team, a full premiere gala, or anything in between. We also offer a complete range of projection and audio equipment to handle any feature, including 2K, 4K DLP projection in 2D and 3D, as well as 35mm and 70mm film projection. On top of that, all our theaters are staffed with skilled projectionists and exceptional engineering teams, to give you a perfect presentation every time. 2 PARAMOUNT THEATRE CUTTING-EDGE FEATURES, LAVISH DESIGN, PERFECT FOR PREMIERES FEATURES • VIP Green Room • Multimedia Capabilities • Huge Rotunda Lobby • Performance Stage in front of Screen • Reception Area • Ample Parking and Valet Service SPECIFICATIONS • 4K – Barco DP4K-60L • 2K – Christie CP2230 • 35mm and 70mm Norelco AA II Film Projection • Dolby Surround 7.1 • 16-Channel Mackie Mixer 1604-VLZ4 • Screen: 51’ x 24’ - Stewart White Ultra Matt 150-SP CAPACITY • Seats 516 DIGITAL CINEMA PROJECTION • DCP - Barco Alchemy ICMP • DCP – Doremi DCP-2K4 • XpanD Active 3D System • Barco Passive 3D System • Avid Media Composer • HDCAM SR and D5 • Blu-ray and DVD • 8 Sennheiser Wireless Microphones – Hand-held and Lavalier • 10 Clear-Com Tempest 2400 RF PL • PIX ADDITIONAL SERVICES AVAILABLE • Catering • Event Planning POST PRODUCTION SERVICES 10 • SecurityScreening Rooms 3 SCREENING ROOMS SHERRY LANSING THEATRE THE ULTIMATE REFERENCE