B.2.2 4 Lanes:

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances

Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances November 2011 i iv . Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances November 2011 i The Delaware Valley Regional Planning The symbol in our logo is Commission is dedicated to uniting the adapted from region’s elected officials, planning the official professionals, and the public with a DVRPC seal and is designed as a common vision of making a great region stylized image of the Delaware Valley. even greater. Shaping the way we live, The outer ring symbolizes the region as a whole while the diagonal bar signifies the work, and play, DVRPC builds Delaware River. The two adjoining consensus on improving transportation, crescents represent the Commonwealth promoting smart growth, protecting the of Pennsylvania and the State of environment, and enhancing the New Jersey. economy. We serve a diverse region of DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding nine counties: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, sources including federal grants from the Montgomery, and Philadelphia in U.S. Department of Transportation’s Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Gloucester, and Mercer in New Jersey. and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Pennsylvania and New Jersey DVRPC is the federally designated departments of transportation, as well Metropolitan Planning Organization for as by DVRPC’s state and local member the Greater Philadelphia Region — governments. The authors, however, are leading the way to a better future. solely responsible for the findings and conclusions herein, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. DVRPC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. -

Approved-Bicycle-Master-Plan-Framework-Report.Pdf

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK abstract This report outlines the proposed framework for the Montgomery County Bicycle Master Plan. It defines a vision by establishing goals and objectives, and recommends realizing that vision by creating a bicycle infrastructure network supported by policies and programs that encourage bicycling. This report proposes a monitoring program designed to make the plan implementation process both clear and responsive. 2 MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK contents 4 Introduction 6 Master Plan Purpose 8 Defining the Vision 10 Review of Other Bicycle Plans 13 Vision Statement, Goals, Objectives, Metrics and Data Requirements 14 Goal 1 18 Goal 2 24 Goal 3 26 Goal 4 28 Goals and Objectives Considered but Not Recommended 30 Realizing the Vision 32 Low-Stress Bicycling 36 Infrastructure 36 Bikeways 55 Bicycle Parking 58 Programs 58 Policies 59 Prioritization 59 Bikeway Prioritization 59 Programs and Policies 60 Monitoring the Vision 62 Implementation 63 Accommodating Efficient Bicycling 63 Approach to Phasing Separated Bike Lane Implementation 63 Approach to Implementing On-Road Bicycle Facilities Incrementally 64 Selecting A Bikeway Recommendation 66 Higher Quality Sidepaths 66 Typical Sections for New Bikeway Facility Types 66 Intersection Templates A-1 Appendix A: Detailed Monitoring Report 3 MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK On September 10, 2015, the Planning Board approved a Scope of Work for the Bicycle Master Plan. Task 4 of the Scope of Work is the development of a methodology report that outlines the approach to the Bicycle Master Plan and includes a discussion of the issues identified in the Scope of Work. -

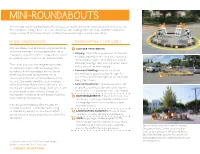

MINI-ROUNDABOUTS Mini-Roundabouts Or Neighborhood Traffic Circles Are an Ideal Treatment for Minor, Uncontrolled Intersections

MINI-ROUNDABOUTS Mini-roundabouts or neighborhood traffic circles are an ideal treatment for minor, uncontrolled intersections. The roundabout configuration lowers speeds without fully stopping traffic. Check out NACTO’s Urban Street Design Guide or FHWA’s Roundabout: An Information Guide Design Guide for more details. 4 DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS COMMON MATERIALS CATEGORIES 1 2 Mini-roundabouts can be created using raised islands 1 SURFACE TREATMENTS: and simple markings. Landscaping elements are an » Striping: Solid white or yellow lines can be used important component of the roundabout and should in conjunction with barrier element to demarcate be explored even for a short-term demonstration. the roundabout space. Other likely uses include crosswalk markings: solid lines to delineate cross- The roundabout should be designed with careful walk space and / or zebra striping. consideration to lane width and turning radius for vehicles. A mini-roundabout on a residential » Pavement Markings: May include shared lane markings to guide bicyclists through the street should provide approximately 15 ft. of 2 clearance from the corner to the widest point on intersection and reinforce rights of use for people the circle. Crosswalks should be used to indicate biking. (Not shown) where pedestrians should cross in advance of the » Colored treatments: Colored pavement or oth- roundabout. Shared lane markings (sharrows) should er specialized surface treatments can be used to be used to guide people on bikes through the further define the roundabout space (not shown). intersections, in conjunction with bicycle wayfinding 2 BARRIER ELEMENTS: Physical barriers (such as route markings if appropriate. delineators or curbing) should be used to create a strong edge that sets the roundabout apart Note: Becase roundabouts allow the slow, but from the roadway. -

How to Drive, Walk & Bike in a Roundabout

What do the signs at a REMEMBER roundabout mean? Look and plan ahead. Slow down! Pedestrians go first. When entering or Roundabout ahead. exiting a roundabout, yield to pedestrians at the crosswalk. Look to the left, find a safe gap, then go. Choose your destination. Start planning your route. Don’t pass vehicles in a roundabout. Remember to signal. There are two entry lanes to the roundabout. Choose the correct lane for your destination. Yield to all traffic in the roundabout including TRANSPORTATION AND pedestrians at crosswalks. ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES Remember you may have 150 Frederick Street, 7th Floor to stop! Kitchener ON N2G 4J3 Canada Phone: 519-575-4558 Flag exit signs identify Email: [email protected] street names for each leg of the roundabout. For more information check our website: www.GoRoundabout.ca Yield here to pedestrians. www.GoRoundabout.ca Updated January 2011 MOWTO HAT IS A ROUNDABOUT? HOW TO DRIVE IN A ROUNDABOUT TIPS FOR CYCLISTS A roundabout is an intersection at which ᮣ Slow down when A cyclist has two choices at a roundabout. Your all traffic circulates counterclockwise approaching a choice will depend on your degree of comfort riding roundabout. in traffic. around a centre island. ᮣ Observe lane signs. For experienced cyclists: Choose the correct ● Ride as if you were driving entry lane. a car. Yield Line ᮣ Expect pedestrians ● Merge into the travel lane Central and yield to them at before the bike lane or shoulder ends. Island all crosswalks. ● Ride in the middle of your lane; don’t hug the curb. Turning right and turning left ᮣ Wait for a gap in ● Use hand signals and signal as if you were a traffic before motorist. -

Traffic-Light Intersections

Give Cycling a Push Infrastructure Implementation Fact Sheet INFRASTRUCTURE/ INTERSECTIONS AND CROSSINGS TRAFFIC-LIGHT INTERSECTIONS Overview Traffic-light intersections are inherently dangerous for cyclists. However, they are indispensable when cyclists cross heavy traffic flows. Cycle-friendly design must make cyclists clearly visible, allow short and easy maneuvers and reduce waiting time, such as a right-turn bypass or an advanced stop-line. On main cycle links, separate cycle traffic light and cycle-friendly light regulation can privilege cycle flows over motorized traffic. Background and Objectives Function Intersections are equipped with a traffic control system when they need to handle large flows of motorized traffic on the busiest urban roads, often with multiple lanes. A cycle-friendly design can greatly improve safety, speed and comfort, by increasing visibility, facilitating maneuvers and reducing waiting time. Scope Traffic-light intersections are always a second-best solution for cyclists, in terms of safety. Actually, traffic light intersections with four branches are very dangerous and should be avoided in general. Dutch guidance states that roundabouts are significantly safer than traffic lights for four- branch intersections of 10,000 to 20,000 pcu/day. In practice, traffic lights are used when an intersection needs to handle large flows of motorized traffic speedily. They can handle up to 30,000 pcu/day, more than is possible with a roundabout. These will typically include at least one very busy distributor road with multiple traffic lanes (50 km/h in the built-up area, higher outside the built-up area). Often, these busy roads are also of great interest as cycle links. -

Building a Bicycle Friendly Neighborhood a Guide for Community Leaders

Building A Bicycle Friendly Neighborhood A Guide for Community Leaders Washington Area Bicyclist Association Building a Bicycle Friendly Neighborhood • Page 1 Washington Area Bicyclist Association © 2013 Suggested Citation: Building a Bicycle Friendly Neighborhood: A Guide for Community Leaders. (2013). Washington Area Bicyclist Association. Washington, D.C. The Washington Area Bicyclist Association is a nonprofit advocacy and education organization representing the metropolitan Washington area bicycling community. Reproduction of information in this guide for non-profit use is encouraged. Please use with attribution. Table of Contents Introduction and How to Use This Guide .....................................................Page 3 How Biking Projects Happen .......................................................................Page 4 Benefits of Biking .........................................................................................Page 7 The Importance of Bike Infrastructure to Get People Biking .................. Page 12 Building Community Support .................................................................... Page 20 Conclusion ...................................................................................................Page 27 Endnotes ..................................................................................................... Page 28 Appendix A: Sources Cited ......................................................................... Page 29 Appendix B: Survey Results ..................................................................... -

Designing for On-Road Bikeways

Designing for Bicyclist Safety Module B DESIGNING ON-ROAD BIKEWAYS LEARNING OUTCOMES Describe features of on-road bikeways Select design criteria for on-road bikeways in various contexts BICYCLE CHARACTERISTICS BICYCLE CHARACTERISTICS Height Handlebar - 36-44 in Eye - 60 in Operating - 100 in Width Physical – 30 in Minimum operating – 48 in Preferred operating – 60 in OLDER BIKEWAY TYPES “Bike Route” “Bike Path” Neither term is clear They are all bikeways BIKEWAY NETWORK Just like roads and sidewalks, bikeways need to be part of an connected network Combine various types, including on and off-street facilities HIERARCHY OF BIKEWAYS Shared-Use Paths Separated Bike Lanes Bike Lanes Shoulders Shared Roadway Photo by Harvey Muller Photo by SCI Photo by Harvey Muller Photo by SCI Designing On-Road Bikeways SHARED ROADWAY Photo by Harvey Muller SHARED ROADWAY Most common— roads as they are Appropriate on low-volume or low-speed 85% or more of a well-connected grid SHARED LANES Unless prohibited, all roads have shared lanes No special features for: Minor roads Low volumes (< 1000 vpd) Speeds vary (urban v. rural) SHARED LANES Supplemental features Pavement markings or “sharrows” Detectors & signal timing SHARED LANE MARKING Lateral position Connect gaps in bike lanes Roadway too narrow for passing Position in intersections & transitions SHARED ROAD SIGNS Ride side-by-side? Chase bicyclist? Warning or regulation? Opposite forces? Philadelphia, PA ...and who “shares”? New Orleans, LA California SHARED ROAD SIGNS -

Bicycle Infrastructure Design

Bicycle Infrastructure Design 2nd of 2 presentations about Bike Infrastructure Last Month: A Picture of Transportation and Infrastructure in Druid Hills This Month: A Look at Cycling and Infrastructure Design April 2018 Gradations of Bicycle Infrastructure Shared Lane Painted Buffered Protected Trail Marking Bike Lane Bike Lane Bike Lane least protected most protected Gradations of Bicycle Infrastructure Shared Lane Marking – “sharrow” In GA, bicycles are allowed in all lanes on all roads* unless specifically marked, “motor vehicles only.” • Roads with “sharrows” are not different from other roads except for marking. • These offer no protection for cyclists. • “Sharrows” may alert drivers to presence of bicycles. • “Sharrows” may give drivers false impression bicycles are allowed only on certain roads or lanes. *Reference: GA laws §40-1-1, §40-6-290, §40-6-291 Gradations of Bicycle Infrastructure Painted Bike Lane Painted bike lanes designate space within a roadway for bicycles. Painted bike lanes do not separate bicycles from traffic. Buffered Bike Lane Buffered bike lanes allow additional designated space for bicycles and improve safety. Buffered bike lanes do not separate bicycles from traffic. Gradations of Bicycle Infrastructure Protected Bike Lane / Cycle-track Separates bicycles from traffic using curbs, bollards, greenspace, etc. Offers protection for cyclists. Can be one-way or two-way. Gradations of Bicycle Infrastructure Multi-use Trails / Paths Typically separated from traffic by greenspace or sometimes curbs. Typically two-way. Does not separate cyclists and pedestrians. U.S. Population as Cyclist Population can be divided into four cycling groups: 1. Strong and Fearless 2. Enthused and Confident 3. Interested but Concerned 4. -

Pop-Up Placemaking Tool Kit Projects That Inspire Change — and Improve Communities for People of All Ages

The Pop-Up Placemaking Tool Kit Projects that inspire change — and improve communities for people of all ages PROTECTED BIKE LANES OUTDOOR SEATING PUBLIC ART ... AND MORE! POP-UP SHOPS AARP is the nation’s largest nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to empowering Americans 50 and older to choose how they live as they age. With nearly 38 million members, plus offices in every state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, AARP strengthens Websites: AARP.org and AARP.org/Livable communities and advocates for what matters most to families, with a focus Email: [email protected] on health security, financial stability and personal fulfillment. The AARP Facebook: /AARPLivableCommunities Livable Communities initiative works nationwide to support the efforts of Twitter: @AARPLivable neighborhoods, towns, cities, counties and rural areas to be livable for Free Newsletter: AARP.org/LivableSubscribe people of all ages. The initiative’s programs include the AARP Network of AARP Age-Friendly States and Communities, the AARP Community Challenge 601 E Street NW “quick-action” grant program and educational publications, including this one Washington, D.C. 20049 and others available at AARP.org/LivableLibrary. Team Better Block is a consulting firm that has pioneered new models for planning and designing public spaces, streets and other community assets. With more than 200 projects in the United States and internationally, Team Better Block works in communities of all sizes and demographics to build the momentum for -

Arvada Bicycle Master Plan

FINAL DRAFT Arvada Bicycle Master Plan SEPTEMBER 2017 ARVADA BICYCLE MASTER PLAN THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK i ARVADA BICYCLE MASTER PLAN Acknowledgments Mayor Marc Williams Arvada City Council Olde Town Stakeholders Nancy Ford, District 1 Karen Miller, Interim BID President Mark McGoff, District 2 Jane Schnabel, Gold Line Advisory Committee John Marriott, District 3 Jason Dirgo, La Dolce Vita David Jones, District 4 Mike Higgins, Klein’s Beer Hall/The Arvada Tavern Don Allard, At-Large Lee Cryer, RTD Bob Fifer, Mayor Pro Tem and At-Large City Committees and Commissions Internal Advisory Team Transportation Advisory Committee Wesley Dismore – Engineering/Project Manager Planning Commission Loretta Daniel – Community Development Jake Nitchals – Community Development Consultant Team John Firouzi – Engineering/Traffic Sarah Washburn – Parks and Urban Design Toole Design Group Jessica Fields Michael McDonnell – Parks Maintenance Bill Schultheiss Christopher Yaney – Streets Ashley Haire Jessica Prosser – City Manager’s Office Geneva Hooten Yelena Onnen – Jefferson County Transportation and Engineering Jessica Zdeb Galen Omerso In collaboration with the citizens of Arvada, and: Spencer Gardner External Advisory Team Felsburg Holt & Ullevig Bob Matter, Assisted Cycling Tours Cady Dawson Cyndi Stovall, Arvada Transportation Committee Kelly Leadbetter Karlyn Armstrong, Arvada Sustainability Advisory Jenny Young Committee (ASAC) Charlie Myers, Bike Jeffco & Wheat Ridge Active Transportation Advisory Team Peter McNutt, Arvada Bicycle Advisory -

17Th Avenue Pop-Up Protected Bike Lane

17th Avenue Pop-Up Protected Bike Lane By: Jessica Ngo, Lydia Jenkins-Sleczkowski, Christina Eldredge, and Christopher Tom March 16, 2020 Executive Summary Purpose The purpose of this report is to attract cycling to a broad group of cyclists by recommending the implementation of protected bike lanes in Santa Cruz. With our limited time, we focused on a critical site where protected bike lanes would be most useful to the surrounding community. 17th Avenue is an essential street due to its connectivity and access to schools and businesses, in addition to its connection to the Arana Gulch bike trail, which connects to downtown Santa Cruz. To widen the appeal of cycling along this street, we recommend implementing protected bike lanes along 17th Avenue from Felt Street through the intersection at Capitola Road. The implementation of protected bike lanes can increase the number of commuters who bike and improve road safety for all types of users. The benefits of protected bike lanes come at a low cost and require minimal infrastructural changes. This Report: ● Assesses the bicycle facilities along 17th Avenue and identifies key segments along the street based on proximity to destinations (schools, businesses, recreation, etc.) and bicycle safety (collisions, traffic volumes, and travel speeds). ● Recommends feasible bike facilities that require minimal change to the already existing street dimensions and follows the National Association of City Transportation Officials Development The 17th Avenue Protected Bike Lanes report was developed as part of a senior seminar group project through the University of California, Santa Cruz. Jessica Ngo, Lydia Jenkins-Sleczkowski, Christina Eldredge, and Christopher Tom are Environmental Studies undergraduate students who worked with the help of Bike Santa Cruz County director Gina Cole and under the supervision of Professor Adam Millard-Ball to develop this report. -

Implementing Bicycle Improvements at the Local Level

IMPLEMENTING BICYCLE IMPROVEMENTS AT THE LOCAL LEVEL PUBLICATION NO. FHWA-98-105 1998 U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION ith the passage of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Effi- ciency Act of 1991 (ISTEA), metropolitan planning organizations W throughout the United States were explicitly required to consider bicyclists in their long-range transportation plans. As a result, many post- ISTEA plans do include ambitious bicycling components intended to increase the levels and safety of bicycle use within the affected communi- ties. In light of these events, the purpose of this document is to provide detailed information on how to implement some of the most useful and popular elements. As a result, the advice contained herein will be most useful for those at the local—typically below the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO)—level working to implement the MPO long-range plans. The goal of bicycle planning at the local level is to provide for bicycle travel within the community. The purpose of doing so is to encourage more bicycling and to reduce the number of serious bicycling crashes and injuries. Building bicycle facilities is a key part of the encouragement side of this effort. But such efforts typically mean focusing on small-scale improvements and local environments. Since the typical bicycle trip is less The goal of bicycle planning at the local level is to provide for bicycle travel within the community. The purpose of doing so is to encourage more bicycling. than two miles in length, regional plans tend to overlook issues of most concern to bicyclists.