UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Millstreet Miscellany

Aubane, Millstreet, Co. Cork. Secretary: Noreen Kelleher, tel. 029 70 360 Email: [email protected] PUBLICATIONS Duhallow-Notes Towards A History, by B. Clifford Three Poems by Ned Buckley and Sean Moylan Ned Buckley's Poems St. John's Well, by Mary O'Brien Canon Sheehan: A Turbulent Priest, by B. Clifford A North Cork Anthology, by Jack Lane andB. Clifford Aubane: Notes On A Townland, by Jack Lane 250 Years Of The Butter Road, by Jack Lane Local Evidence to theT5evon Commission, by Jack Lane Spotlights On Irish History, by Brendan Clifford. Includes chapters on the Battles of Knocknanoss and Knockbrack, Edmund Burke, The Famine, The Civil War, John Philpot Curran, Daniel O'Connell and Roy Foster's approach to history. The 'Cork Free Press' In The Context Of The Parnell Split: The Restructuring Of Ireland, 1890-1910 by Brendan Clifford Aubane: Where In The World Is It? A Microcosm Of Irish History In A Cork Townland by Jack Lane Piarais Feiriteir: Danta/Poems, with translations by Pat Muldowney Audio tape of a selection of the poems by Bosco O 'Conchuir Elizabeth Bowen: "Notes On Eire". Espionage Reports to Winston Churchill, 1940-42; With a Review of Irish Neutrality in World War 2 by Jack Lane and Brendan Clifford The Life and Death of Mikie Dineen by Jack Lane Aubane School and its Roll Books by Jack Lane Kilmichael: the false surrender. A discussion by Peter Hart, Padraig O'Cuanachain, D. R. O 'Connor Lysaght, Dr Brian Murphy and Meda Ryan with "Why the ballot was followed by the bullet" by Jack Lane and Brendan Clifford. -

Cork City and County Archives Index to Listed Collections with Scope and Content

Cork City and County Archives Index to Listed Collections with Scope and Content A State of the Ref. IE CCCA/U73 Date: 1769 Level: item Extent: 32pp Diocese of Cloyne Scope and Content: Photocopy of MS. volume 'A State of The Diocese of Cloyne With Respect to the Several Parishes... Containing The State of the Churches, the Glebes, Patrons, Proxies, Taxations in the King's Books, Crown – Rents, and the Names of the Incumbents, with Other Observations, In Alphabetical Order, Carefully collected from the Visitation Books and other Records preserved in the Registry of that See'. Gives ecclesiastical details of the parishes of Cloyne; lists the state of each parish and outlines the duties of the Dean. (Copy of PRONI T2862/5) Account Book of Ref. IE CCCA/SM667 Date: c.1865 - 1875 Level: fonds Extent: 150pp Richard Lee Scope and Content: Account ledger of Richard Lee, Architect and Builder, 7 North Street, Skibbereen. Included are clients’ names, and entries for materials, labourers’ wages, and fees. Pages 78 to 117 have been torn out. Clients include the Munster Bank, Provincial Bank, F McCarthy Brewery, Skibbereen Town Commissioners, Skibbereen Board of Guardians, Schull Board of Guardians, George Vickery, Banduff Quarry, Rev MFS Townsend of Castletownsend, Mrs Townsend of Caheragh, Richard Beamish, Captain A Morgan, Abbeystrewry Church, Beecher Arms Hotel, and others. One client account is called ‘Masonic Hall’ (pp30-31) [Lee was a member of Masonic Lodge no.15 and was responsible for the building of the lodge room]. On page 31 is written a note regarding the New Testament. Account Book of Ref. -

Communities of Science: the Queen's Colleges and Scientific Culture in Provincial Ireland, 1845-75' (Phd, National University of Ireland, Galway, 2006), Pp

Juliana Adelman PhD NUIGalway 2006 Communities of science Communities of science: the Queen’s Colleges and scientific culture in provincial Ireland, 1845-1875 Juliana Adelman Supervisor: Dr Aileen Fyfe Department of History Faculty of Arts National University of Ireland, Galway Submitted for the degree of PhD September 2006 55 Juliana Adelman PhD NUIGalway 2006 Communities of science Contents Acknowledgements iii List of figures iv List of abbreviations vi Abstract xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Science in a divided community: politics, religion and 15 controversy in the founding of the Queen’s Colleges 3 Science in the community: voluntary societies in Cork 55 4 ‘Practical’ in practice: the agriculture diploma in Belfast 93 5 Improving museums: showcases of the natural world in 135 provincial Ireland 6 An invisible scientific community: the ‘Galway professors’ 172 and the Eozoön controversy 7 Conclusion 210 Bibliography 221 56 Juliana Adelman PhD NUIGalway 2006 Communities of science Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr Aileen Fyfe, for guidance and encouragement throughout the researching and writing of this dissertation. Her conscientious reading (and re-reading) of multiple drafts has certainly made this dissertation much more than it might have been. I am also indebted to my husband, Martin Fanning, for his patience and emotional support as well as for reading several drafts of this work. Dr Elizabeth Neswald, Dr Mary Shine- Thompson and Dr Mary Harris also deserve thanks for taking the time to read part or all of the dissertation; their comments have greatly improved the final product. Thanks to the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences, whose grant to Dr Fyfe provided my salary and travel allowance throughout the project, and the Moore Centre at the National University of Ireland, Galway (formerly the Centre for the Study of Human Settlement and Historical Change), which administered the grant and generously provided me with space to work. -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song. -

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU of MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT by WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO W.S. Witness Liam De Róiste No. 2 Janemou

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO W.S. Witness Liam de Róiste No. 2 Janemount, Sunday's Well, Cork. Identity. Member, Coiste Gnotha, Gaelic League. Member, Dáil Éireann, 1918-1923. Subject. National Activities, 1899-1918. Irish Volunteers, Cork City, 1913-1918. Conditions,if any, Stipulatedby Witness. Nil. File No FormB.S.M.2 STATSUENT OF LIAM DR ROISTE. CERTIFICATE BY THE DIRECTOR OF THE BUREAU. This statement by Liam de Roiste consists of 385 pages, signed on the last page by him. Owing to its bulk it has not been possible for the Bureau, with the appliances at its disposal. to bind it in one piece, and it has, therefore, for convenience in stitching, been separated into two sections, the first, consisting of pages 1-199, and the other, of pages 200-385, inclusive. The separation into two sections baa no other significance. The break between the two sections occurs in the middle of a sentence, the last words in section I, on page 199, being "should be", and the first in section II, on page 200, being "be forced". A certificate in these terms, signed by me as Director of the Bureau, is bound into each of the two parts. McDunphy DIRECTOR. (M. McDunphy) 27th November, 1957. STATIENT BY LIAM DE R0ISTE 2. Janemount, Sundav's Woll. Cork. This statement was obtained from Mr. de Roiste, at the request of Lieut.-Col. T. Halpin, on behalf of the Bureau of Military History, 26 Westland Row, Dublin. Mr. do Hoists was born in Fountainstown in the Parish of Tracton, Co. -

Irish Culture

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Thomas Davis's education policies: theory and practice Author(s) Conneally, John Publication date 2014 Original citation Conneally, J. 2014. Thomas Davis's education policies: theory and practice. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2014, John Conneally http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1553 from Downloaded on 2021-10-04T16:18:04Z Thomas Davis’s Education Policies: Theory and Practice John Conneally Thesis presented in fulfillment of the regulations governing the award of PhD. Head of Department: Professor K. Hall Supervisor: Dr F. Long Submitted to: School of Education, University College Cork: National University of Ireland January 2014 1 Contents Chapter 1: In what way was Thomas Davis an educationalist? ........................................4 Introduction .........................................................................................................................4 1.1 Definition of an educationalist.......................................................................................8 1.2 Davis’s Nationalist Philosophy...................................................................................12 1.3 Contemporary perspectives on shortcomings in Irish education…………………….19 1.4 Davis’s national education .........................................................................................266 -

Dictionary of Irish Biography

Dictionary o f Irish Biography Relevant Irish figures for Leaving Cert history CONTENTS PART 3. Pursuit of sovereignty and the impact PART 1. of partition Ireland and 1912–1949 the Union 138 Patrick Pearse 6 Daniel O’Connell 150 Éamon de Valera 18 Thomas Davis 172 Arthur Griffith 23 Charles Trevelyan 183 Michael Collins 27 Charles Kickham 190 Constance Markievicz 31 James Stephens 193 William Thomas Cosgrave C 35 Asenath Nicholson 201 James J. McElligott 37 Mary Aikenhead 203 James Craig O 39 Paul Cullen 209 Richard Dawson Bates 46 William Carleton 211 Evie Hone N 49 William Dargan T PART 4. PART 2. The Irish diaspora E Movements for 1840–1966 political and N 214 John Devoy social reform 218 Richard Welsted (‘Boss’) Croker T 1870–1914 221 Daniel Mannix 223 Dónall Mac Amhlaigh 56 Charles Stewart Parnell 225 Paul O’Dwyer S 77 John Redmond 228 Edward Galvin 87 Edward Carson 230 Mother Mary Martin 94 Isabella Tod 96 Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington 99 James Connolly 107 Michael Davitt PART 5. 116 James Larkin Politics in 122 Douglas Hyde Northern Ireland 129 William Butler Yeats 1949–1993 239 Terence O’Neill 244 Brian Faulkner 252 Seamus Heaney Part 1. Ireland and the Union Daniel O’Connell O’Connell, Daniel (1775–1847), barrister, politician and nationalist leader, was born in Carhen, near Caherciveen, in the Iveragh peninsula of south-west Kerry, on 6 August 1775, the eldest of ten children of Morgan O’Connell (1739–1809) and his wife, Catherine O’Mullane (1752–1817). Family background and early years Morgan O’Connell was a modest landowner, grazier, and businessman. -

Some Cork Lawyers from 1199

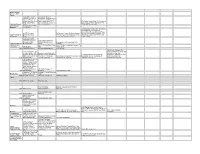

Medieval Gaol, Queen's Old Castle Corporation votes 12 In Reign of James 1 years tax revenue to Courthouse and Gaol in the Alderman Roche to Castle of Cork (King's Old build a new Gaol, three Castle) taken down 1718, City Prison, North Gate 1715 built to a bridges and Market later Courthouse on site of desigm by Coltsman, Sunday's Well 1620 Cork Gaol House Queens Old Castle Prison built in same style Chief Justice Nicholas Walsh 1576, Munster JCHAS1904 Lord President of Munster: Sir William St. Ledger will 1657 mentions Councellor in Fermoy Richard Fisher d 1607 Sir Henry Sir George Carew, Siir Henry Becher his own wife Gertude Doneraile, 1671 Lord Presidency Brouder buried St. 1604 (no record of circuits during his William St. Ledger (Cork Archives U of Munster Marys term), Lord Danveers 1610, 675/52), died Proposals for wall around New Gaol at Gill Abbey known by Prison demolished mid the name of Mrs. 1960 for UCC Science Front portica still extant built 1818 1790 Cork Prison Moore's fields Block (Windle) 19th November Gaoler, County Gaol South John T Collins, newspaper extracts, Dr 1759 Died Dan Murphy gate Casey 2374 1769 Christopher Beere Keeper of Marshallsea Cork Journal Skibbereen Bridewell The Cork Commitals 1,145, Sheriff averager 91 felony and average number 194, Bandon County Bridewell assaults average 22 females criminal minors jurisdiction High Sheriff and Clonakilty Bridewell Sovreigh and Bridgetown (Skibbereen) The debtors 28, debtors 80, Provost 271 commitals Rosscarbery Bridewlll Comon Gaol, 50 Seneschal Rev. Dr. townsend 20 Lord of the Manor 50 1818 criminals 228 average numbe 21 commotals averager12, commitals average 2 commitlas average 12 J Welsh Esq Keeper of City Gaol, Rev Dr Quarry, Inspector and Chaplain of City Gaol and Bridewell, Rev John Falves (Falvey?) Roman Catholic Chaplin of Cith Gaol J.P. -

Conversations with Carlyle

• ;?:: ;;,;, h, , ;'o : ^y.r;,-'^; >-y I :y; : _ : r. 1 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013460948 CONVERSATIONS WITH CARLYLE 'kvttwv- Conversations WITH Carlyle SIR CHARLES GAVAN DUFFY, K.C.M.G. NEW YORK: CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS, 743 & 745 BROADWAY. 1892. |.UNIVEfigJWl " •. ^pm 11 ifi ii ' ^fJr PR PREFACE. These papers were originally published in the Contemporary Review, chiefly For the purpose of presenting a more real, as well as a more human, picture of the philosopher of Chelsea than readers have been accustomed to of late. It has been no little gratification to me to receive letters from cultivated and thoughtful people, declaring that the conversations and corres- pondence, and, in some degree, the testimony of the author, had enabled them to accept anew an estimate of Carlyle which they had relinquished with pain, and to be assured that the nature and habits of the eminent man were not unworthy of his position as a teacher and leader of his age. They have incidentally served another purpose : they furnish a striking gallery of portraits, and an unique body of criticism on the writers of the century, by one of the most impressive painters of men that ever existed. The criticisms have some- times been called harsh and unjust, by impatient vi PREFACE. -

How Poetry Shaped Nationalism in Georgia and Ireland

Young and Drunk: How Poetry Shaped Nationalism in Georgia and Ireland Author: Nina Nadirashvili Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108696 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, May 2019 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. YOUNG AND DRUNK: HOW POETRY SHAPED NATIONALISM IN GEORGIA AND IRELAND by Ninutsa Nadirashvili Submitted in partial fulfillment of graduation requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Boston College International Studies Program May 2019 Advisor: Prof. Paul Christensen Advisor: Prof. Marjorie Howes Signature: Signature: IS Thesis Coordinator: Prof. Hiroshi Nakazato Signature: © Ninutsa Nadirashvili 2019 Abstract Contemporary public perceptions of nationalism see the concept as a toxic ideology of isolationist politicians. In contrast, through an analysis of work produced by public servants whose identities are tied more closely with those of artists than politicians, this thesis shifts focus to nationalist sentiments built around inclusivity. Using poems of Ilia Chavchavadze and Thomas Davis, this text serves as a comparative overview of nation-building strategies within Georgia and Ireland. The importance of land, myths, heroic characters, motherly figures, and calls to self-sacrifice are present in poems of both nations, uniting them in the struggle against colonial oppression and offering a common formula for creating a national identity. To Kato. For when she wants to know. Acknowledgements Multitudes of gratitude are due to Prof. Marjorie Howes and Prof. Paul Christensen. Only through your collaborative efforts could this thesis have come together. I would also like to thank Prof. -

Young Ireland in Cork, 1840-1849

YOUNG IRELAND IN CORK, 1840-1849 ‘There is no such party as that styled Young Ireland’ snapped Daniel O’Connell in July 1845 in the course of a heated exchange with Thomas Davis.1 In this he was at once both correct and mistaken. Young Ireland was never separate from O’Connellism until 1847, and yet it was much more than a ginger group within a larger movement. It was a way of thinking, of reacting (sometimes unreasonably) against the ideas of the past, and of challenging political realities with political ideals. What was true of Young Ireland island-wide was particularly evident in the experience of that group in Cork city, where the tensions of the 1840s can be variously interpreted in terms of social class, political ideology, family rivalry and unashamed scrambling for the perks of office. This was a new era in Irish urban politics. In Cork, as elsewhere, the successive reforming measures of Emancipation (1829), parliamentary reform (1832) and muncicipal reform (1840) had driven protestant society into a position of permanent political minority, replacing it with a (largely) catholic elite characterised by all the self-confidence of the arriviste.2 But such self-confidence did not go unchallenged, either by those sub-groups who had failed to make it into office under the new dispensation, or by those within the elite whose age, educational background and ideological bent made them question their own recent heritage. Young Ireland in Cork originated within this latter group – the sons (and, to a lesser extent, daughters) of the successful elite which had helped to displace political protestantism in the city over the previous two decades. -

CARLOVIANA 2017 Edition Front Cover Picture No

Page 1 Edited_Layout 1 21/10/2016 10:41 Page 1 1 CARLOVIANA 2017 Edition Front cover picture No. 65 I,S.S.N. 0790 - 0813 Articles Changing attitudes of the 1916 Rising ........................................... 4 Carlow Blue limestones ........................................................................... 9 Portrait of a Young Irelander Thomas Davis .. ...................................... 14 The Ballybar Races (1769-1900).............................................................. 20 A devout priest & devoted patriot ........................................................... 24 The Rolettes Showband .......................................................................... 49 Carlow. QuadrupleLough. Quadruplex Lacus ............................ 52 List of claimants from Carlow for damages during The Peace Tower at Messines, Belgium. Easter week 1916 . .................................................................................... 55 Built as a memorial to those Irishmen of The changing face of Carlow town ......................................................... 56 both the Nationalist and Unionist tradi- tions who died in World War I, this mon- Colonal Dudley Bagenal the Jacobite (1638-1712) ............................... 59 ument stands also as a symbol of The Red Lad and Blunt: Hacketstown Poachers of the 20th cent . .... 71 reconciliation between those traditions. Dolmens in Carlow .................................................................................. 76 The Borris Railway Line and Viaduct ..................................................