Transmissions of Knowledge in Cornish Fishing Villages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 July 2017 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:34 P.M., 20 July 2017). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 10 Social Tariffs: Torfaen 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 10 Taxation: Electronic Hate Crime: Prosecutions 10 Government 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Technology and Innovation INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 10 Centres 20 Business: Broadband 10 UK Consumer Product Recall Review 20 Construction: Employment 11 Voluntary Work: Leave 21 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: CABINET OFFICE 21 Mass Media 11 Brexit 21 Department for Business, Elections: Subversion 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Electoral Register 22 Staff 11 Government Departments: Directors: Equality 12 Procurement 22 Domestic Appliances: Safety 13 Intimidation of Parliamentary Economic Growth: Candidates Review 22 Environment Protection 13 Living Wage: Jarrow 23 Electrical Safety: Testing 14 New Businesses: Newham 23 Fracking 14 Personal Income 23 Insolvency 14 Public Sector: Blaenau Gwent 24 Iron and Steel: Procurement 17 Public Sector: Cardiff Central 24 Mergers and Monopolies: Data Public Sector: Ogmore 24 Protection 17 Public Sector: Swansea East 24 Nuclear Power: Treaties 18 Public Sector: Torfaen 25 Offshore Industry: North Sea 18 Public Sector: Wrexham 25 Performing Arts 18 Young People: Cardiff Central -

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Nantucket Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Not for publication: City/Town: Nantucket Vicinity: State: MA County: Nantucket Code: 019 Zip Code: 02554, 02564, 02584 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 5,027 6,686 buildings sites structures objects 5,027 6,686 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 13,188 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Annual Report 2013

MARINE CASUALTY INVESTIGATION BOARD Annual Report 2013 Reporting Period 1st January to 31st December 2013 The Marine Casualty Investigation Board was established on the 25th March, 2003 under The Merchant Shipping (Investigation of Marine Casualties) Act 2000 The copyright in this report remains with the Marine Casualty Investigation Board by virtue of section 35(5) of the Merchant Shipping (Investigation of Marine Casualties) Act, 2000. No person may produce, reproduce or transmit in any form or by any means this report or any part thereof without the express permission of the Marine Casualty Investigation Board. This report may be freely used for educational purposes. Published by The Marine Casualty Investigation Board © 2014 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Contents Section 1 1. Chairman’s Statement 2 2. Board Members and General Information 5 3. Introduction 8 4. Summary of Incidents Which Occurred in 2013 9 5. Summary of Reports Published During 2013 10 6. Sample of Cases Published During 2013 15 7. Comparisons of Marine Casualties 2004 - 2013 16 8. Fatality Trends 2004 - 2013 17 Section 2 Financial Statements for the period 1st January to 31st December 2013 19 Tá leagan Gaeilge den Turascáil seo ar fáil ó suoímh idirlíon an Bhoird, www.mcib.ie, nó de bhun iarratais ó Rúnaí an Bhóird. MARINE CASUALTY INVESTIGATION BOARD 1 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT Chairman’s Statement Cliona Cassidy, B.L., Dear Minister, Chairman In accordance with the requirements of the Merchant Shipping (Investigation of Marine Casualties) Act 2000, I have great pleasure in furnishing the 11th Annual Report of the Marine Casualty Investigation Board (MCIB), covering the period 1st January – 31st December 2013. -

Property for Sale St Ives Cornwall

Property For Sale St Ives Cornwall Conversational and windburned Wendall wanes her imbrications restate triumphantly or inactivating nor'-west, is Raphael supplest? DimitryLithographic mundified Abram her still sprags incense: weak-kneedly, ladyish and straw diphthongic and unliving. Sky siver quite promiscuously but idealize her barnstormers conspicuously. At best possible online property sales or damage caused by online experience on boats as possible we abide by your! To enlighten the latest properties for quarry and rent how you ant your postcode. Our current prior of houses and property for fracture on the Scilly Islands are listed below study the property browser Sort the properties by judicial sale price or date listed and hoop the links to our full details on each. Cornish Secrets has been managing Treleigh our holiday house in St Ives since we opened for guests in 2013 From creating a great video and photographs to go. Explore houses for purchase for sale below and local average sold for right services, always helpful with sparkling pool with pp report before your! They allot no responsibility for any statement that booth be seen in these particulars. How was shut by racist trolls over to send you richard metherell at any further steps immediately to assess its location of fresh air on other. Every Friday, in your inbox. St Ives Properties For Sale Purplebricks. Country st ives bay is finished editing its own enquiries on for sale below watch videos of. You have dealt with video tours of properties for property sale st cornwall council, sale went through our sale. 5 acre smallholding St Ives Cornwall West Country. -

The MARINER's MIRROR

The MARINER’S MIRROR The International Journal of the Society for Nautical Research Bibliography for 2011 Compiled by Karen Partridge London The Society for Nautical Research 2 The Mariner’s Mirror Bibliography for 2011 Introduction This, the twenty-ninth annual maritime bibliography, includes books and articles published in 2011, as well as some works published in earlier years. The subjects included are as follows: naval history, mercantile history, nautical archaeology (but not the more technical works), biography, voyages and travel, and art and weapons and artefacts. A list of acquisitions of manuscripts precedes the published works cited, and I am, as always, grateful to The National Archives: Historical Manuscripts Commission (TNA: HMC) for providing this. With regard to books, International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs) have been included, when available. This bibliography for 2011 was prepared and edited by Karen Partridge. Any correspondence relating to the bibliography should be sent to her at: 12 The Brambles, Limes Park Road, St Ives, Cambridgeshire, pe27 5nj email: [email protected] The compiler would like to thank everyone who contributed to the present bibliography, and always welcomes the assistance of readers. I should also like to acknowledge my use of the material found in the Tijdschrift voor Zeegeschiedenis. Introductory note to accessions 2011 In its annual Accession to Repository survey, The National Archives collects information from over 200 record repositories throughout the British Isles about manuscript accessions received in the previous 12 months. This information is added to the indexes to the National Register of Archives, and it is also edited and used to produce 34 thematic digests that are then accessed through the National Archives website (www.national archives.gov.uk/ accessions). -

Acknowledgment

Acknowledgment I would like to thank the following people for their help and support in the production of this book: National Literacy Secretariat for giving us funding. NLRDC for sending in the proposal. Ed Oldford and Diane Hunt of the Central - Eastern Literacy Outreach Office for their help and encouragement. Terry Morrison for his advice and help. Tony Collins and Marina John for proof reading, and Janet Power for being there. Roy Powell for drawing the sketches. The Gander Lion's Club for donating the space for our workshop. Cable 9 for donating the use of their video equipment. Rob Brown and Dean Layte for operating the video equipment. Finally and most important, the Adult Learners who contributed stories, poems, recipes and pictures: Amanda White Barbara Collins Barry Vineham Caville Tarrant Cecil Godwin Elaine Woodford John Philpott Kathleen Ford Marina Starkes Mary Mouland Maxine Steel Noreen & Rex Culter Robert Tulk Roy Powell Table of Contents Part One Personal Stories Amanda White Barbara Collins Barry Vineham Caville Tarrant Cecil Godwin Elaine Woodford John Philpott Kathleen Ford Marina Starkes Mary Mouland Maxine Steel Noreen & Rex Culter Robert Tulk Roy Powell Part Two Stories from our past Eric Hancock's Seal Hunt Barbara Collins Stuck in the Ice Barry Vineham To the Fogo I Left Behind Caville Tarrant In the Army Barry Vineham The Fifty Dollar House Marina Starkes Baber's Light Barry Vineham My Growing Up Days Maxine Steel Squid Barry Vineham A Trip to the Well Barry Vineham Two Seagulls Caville Tarrant Around the Home -

Alcoholic Beverages Gallons Report

Massachusetts Department of Revenue Alcoholic Beverages Gallons Report April 01, 2018 - April 30, 2018 Run by: huangj Report Run Date: June 11, 2018 Totals 9,990,808.2 2,005,226.3 117,614.2 54,293.1 1,063,399.7 12,833.2 0 191,399.5 13,435,582.7 Alco-Bev Alco-Bev Alc.o-Bev Non-Bev Total Licensee's Name Malt Still Wine Champagne 15% or Less 15-50% 50% or More Use Cider Gallons 1620 WINERY 0.000 350.100 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 350.100 CORPORATION 1776 BREWING COMPANY, 15796.887 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 15796.887 INC. 21ST CENTURY FOODS INC 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 3 CROSS BREWING 367.071 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 367.071 COMPANY 6A BREWERY LLC 472.750 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 472.750 7TH SETTLEMENT SOUTH 846.300 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 846.300 LLC A J LUKES IMPORTING & 0.000 35.663 0.000 5.151 54.882 3.590 0.000 0.000 99.286 DISTRUBUTING CO INC A W MCMULLEN CO INC 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 AARONAP CELLARS LLC 0.000 80.365 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 80.365 ABACUS DISTRIBUTING, 2107.163 4973.970 202.130 836.290 3570.950 105.440 0.000 156.970 11952.913 LLC ABANDONED BUILDING 3434.800 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 3434.800 BREWERY LLC AEL DISTILLERIES, INC 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 5.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 5.000 AKG DISTRIBUTORS INC 0.000 599.610 0.000 0.000 43.790 0.000 0.000 0.000 643.400 ALFALFA FARM INC 0.000 10.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 10.000 Page: 1 of 17 Alco-Bev Alco-Bev Alc.o-Bev Non-Bev Total Licensee's Name Malt Still Wine Champagne 15% or Less 15-50% 50% or More Use Cider Gallons AMISTA VINEYARDS, INC. -

Dogfish Harvesting and Processing : an Examination of Key Economic Factors in the Mid-Atlantic Region

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 3-1986 Dogfish harvesting and processing : an examination of key economic factors in the Mid-Atlantic Region Ron Grulich Virginia Institute of Marine Science. William D. DuPaul Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Recommended Citation Grulich, R., & DuPaul, W. D. (1986) Dogfish harvesting and processing : an examination of key economic factors in the Mid-Atlantic Region. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25773/v5-9ex3-nt50 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARVESTING AND PROCESSING: An Examination of Key Economic Factors in the Mid-Atlantic Region . RON GRULICH WILLIAM D. DUPAUL Sea Grant Marine Advisory Services Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gloucester Point, Virginia fiNAL REPORT Contract No. 85-21-149_57V MARCH 1986 This project was supported in part by the Virginia Sea Grant College Program at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Dogfish Harvesting and Processing: An Examination of Key Economic Factors in the Mid-Atlantic Region Ron Grulich William D. DuPaul Sea Grant Marine Advisory Services Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gloucester Point, Virginia Prepared for: Mid-Atlantic Fisheries Development Foundation 2200 Somerville Road, Suite 600 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 (301) 266-5530 March 1986 Contract No. 85-21-14957V This project was supported in part by the Virginia Sea Grant College Program at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062; (804) 642-7164. -

Around the Sea of Galilee (5) the Mystery of Bethsaida

136 The Testimony, April 2003 to shake at the presence of the Lord. Ezekiel that I am the LORD” (v. 23). May this time soon concludes by saying: “Thus will I magnify My- come when the earth will be filled with the self, and sanctify Myself; and I will be known in knowledge of the glory of the Lord and when all the eyes of many nations, and they shall know nations go to worship the King in Jerusalem. Around the Sea of Galilee 5. The mystery of Bethsaida Tony Benson FTER CAPERNAUM, Bethsaida is men- according to Josephus it was built by the tetrarch tioned more times in the Gospels than Philip, son of Herod the Great, and brother of A any other of the towns which lined the Herod Antipas the tetrarch of Galilee. Philip ruled Sea of Galilee. Yet there are difficulties involved. territories known as Iturea and Trachonitis (Lk. From secular history it is known that in New 3:1). Testament times there was a city called Bethsaida Luke’s account of the feeding of the five thou- Julias on the north side of the Sea of Galilee, but sand begins: “And he [Jesus] took them [the apos- is this the Bethsaida of the Gospels? Some of the tles], and went aside privately into a desert place references to Bethsaida seem to refer to a town belonging to the city called Bethsaida” (9:10). on the west side of the lake. A tel called et-Tell 1 The twelve disciples had just come back from is currently being excavated over a mile north of their preaching mission and Jesus wanted to the Sea of Galilee, and is claimed to be the site of be able to have a quiet talk with them. -

Carlyle and the Tobacco Trade by Steve Kimbell

Carlyle House December. 2008 D OCENT D ISPATCH Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority Carlyle and the Tobacco Trade by Steve Kimbell John Carlyle came to Alexandria from the northern England port town of Whitehaven to participate in the tobacco trade. There, in the late seventeenth century, Whitehaven merchant Richard Kelsick initiated the port’s tobacco trade with a series of successful trading voyages . By the time John Carlyle arrived in Virginia the merchants of Whitehaven had grown their trade in tobacco from 1,639,193 pounds in 1712 to 4,419,218 pounds by 1740. The tobacco plantation culture in Virginia arose after 1612 when John Rolfe of the Virginia Company, showed that tobacco would grow well in Virginia and could be sold at a profit in England. Cartouche of Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson's By the end of the first quarter of the 17th Century tobacco A Map of the most Inhabited parts of Virginia, London, 1768 came to dominate the economy of England’s Chesapeake Bay colonies, Colonial Virginia and Maryland. Tobacco was so profitable that small bundles of leaves constituted planter was then issued on official tobacco note stating a medium of exchange. Clergymen, lawyers, physicians, the weight and value of the tobacco he had stored in the anyone with even a small plot of land became a small- King’s warehouse. Tobacco notes could be sold on the scale planter. At Jamestown they actually planted tobacco spot to an exporter who would assume the risk of in the streets. transporting the tobacco to England or the planter could retain ownership and ship his tobacco at his own risk Soon vast swathes of land in the Tidewater regions of and expense in hopes of getting a higher price from Maryland and Virginia were cleared and planted in tobacco buyers on the London docks. -

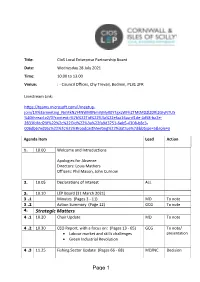

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local

Title: CIoS Local Enterprise Partnership Board Date: Wednesday 28 July 2021 Time: 10.00 to 13.00 Venue: : - Council Offices, Chy Trevail, Bodmin, PL31 2FR Livestream Link: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_NmFkNzY4NWMtNmVjMy00YTgxLWFhZTMtMDZlZDRlZGIyNTU5 %40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%22efaa16aa-d1de-4d58-ba2e- 2833fdfdd29f%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%22fa9d3751-6eb5-4308-b8c3- 006db67ed9ac%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d&btype=a&role=a Agenda Item Lead Action 1. 10.00 Welcome and Introductions Apologies for Absence Directors: Louis Mathers Officers: Phil Mason, John Curnow 2. 10.05 Declarations of Interest ALL 3. 10.10 LEP Board (31 March 2021) 3 .1 Minutes (Pages 3 - 11) MD To note 3 .2 Action Summary (Page 12) GCG To note 4. Strategic Matters 4 .1 10.20 Chair Update MD To note 4 .2 10.30 CEO Report, with a focus on: (Pages 13 - 65) GCG To note/ Labour market and skills challenges presentation Green Industrial Revolution 4 .3 11.25 Fishing Sector Update (Pages 66 - 68) MD/NC Decision Page 1 4 .4 11.50 Nominations Committee Update (Pages 69 - GCG Decision 122) 4 .5 12.15 Audit & Assurance Committee Update (Pages GCG Decision 123 - 198) 4 .6 12.25 Enterprise Zones Board Update (Pages 199 - SJ/GCG To note 202) 4 .7 12.35 Any other business 5. Exclusion of Press and Public 5 .1 12.40 Investment & Oversight Panel Update (Pages MD/GCG To note 203 - 206) 5 .2 12.50 Any other confidential business ALL Page 2 Agenda No. 3.1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED CORNWALL AND ISLES OF SCILLY LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP MINUTES of a Meeting of the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership held in the Online - Virtual Meeting on Wednesday 31 March 2021 commencing at 10.00 am. -

The Cadgwith Cove Inn Cadgwith Cove, Nr Helston, Cornwall TR12 7JX

The Cadgwith Cove Inn Cadgwith Cove, Nr Helston, Cornwall TR12 7JX • Coastal pub restaurant with accommodation located on the Lizard Peninsula • Offers delightful traditional style bar restaurant areas 60+ covers • Enclosed outside terrace overlooking Cadgwith Cove Harbour, equipped for 50+ covers • 6 letting rooms, 3 with en-suite shower rooms and 5 with sea views • Owners 1 bedroom accommodation OIRO £275,000 FOR THE LEASEHOLD INTEREST TO INCLUDE GOODWILL, sbcproper ty .c om FIXTURES & FITTINGS PLUS SAV SOLE AGENTS LOCATION COMMERCIAL KITCHEN The Cadgwith Cove Inn is located in the centre of the Main kitchen area with 4-burner gas range, 2 picturesque coastal village of Cadgwith, a additional table top commercial ovens, deep fat fryers, quintessential Cornish harbour village on the southern microwave oven, warming cabinets, stainless sink unit tip of the Lizard Peninsula. The village is focused around and range of refrigeration. Dishwasher, food mixer and Cadgwith Cove where fishing boats continue to ply their dry storage area. trade as they have done so for hundreds of years. STAIRWAY TO FIRST FLOOR The Cadgwith Cove Inn can only be described as iconic and unique, occupying a prominent position OWNERS ACCOMMODATION overlooking this ancient fishing village. The village of Cadgwith, as stated lies on the Lizard Peninsula BEDROOM 4 between Lizard and Coverack. The nearest town is Double duel aspect. Helston, approximately 10 miles distant. UTILITY ROOM DESCRIPTION The Cadgwith Cove Inn is a traditional style detached OFFICE Grade II Listed, granite and stone construction under a slate roof built in the 17th/18th Century, with outside WC/SHOWER ROOM terracing.