Exclaves Honoré M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 1

Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 1 Condominiums And Shared Sovereignty Abstract As the United Kingdom (UK) voted to leave the European Union (EU), the future of Gibraltar, appears to be in peril. Like Northern Ireland, Gibraltar borders with EU territory and strongly relies on its ties with Spain for its economic stability, transports and energy supplies. Although the Gibraltarian government is struggling to preserve both its autonomy with British sovereignty and accession to the European Union, the Spanish government states that only a form of joint- sovereignty would save Gibraltar from the same destiny as the rest of UK in case of complete withdrawal from the EU, without any accession to the European Economic Area (Hard Brexit). The purpose of this paper is to present the concept of Condominium as a federal political system based on joint-sovereignty and, by presenting the existing case of Condominiums (i.e. Andorra). The paper will assess if there are margins for applying a Condominium solution to Gibraltar. Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 2 Condominium in History and Political Theory The Latin word condominium comes from the union of the Latin prefix con (from cum, with) and the word dominium (rule). Watts (2008: 11) mentioned condominiums among one of the forms of federal political systems. As the word suggests, it is a form of shared sovereignty involving two or more external parts exercising a joint form of sovereignty over the same area, sometimes in the form of direct control, and sometimes while conceding or maintaining forms of self-government on the subject area, occasionally in a relationship of suzerainty (Shepheard, 1899). -

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: the Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: The Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises A report by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Village Capital With the support of: Ross Baird Lily Bowles Saurabh Lall The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) is a global network of organizations that propel entrepreneurship in emerging markets. ANDE members provide critical financial, educational, and busi- ness support services to small and growing businesses (SGBs) based on the conviction that SGBs will create jobs, stimulate long-term economic growth, and produce environmental and social benefits. Ultimately, we believe that SGBS can help lift countries out of poverty. ANDE is part of the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies organization. For more information please visit www.aspeninstitute.org/ande. Village Capital Village Capital sources, trains, and invests in impactful seed-stage enter- prises worldwide. Inspired by the “village bank” model in microfinance, Village Capital programs leverage the power of peer support to provide opportunity to entrepreneurs that change the world. Our investment pro- cess democratizes entrepreneurship by putting funding decisions into the hands of entrepreneurs themselves. Since 2009, Village Capital has served over 300 ventures on five continents building disruptive innovations in agriculture, education, energy, environmental sustainability, financial services, and health. For more information, please visit www.vilcap.com. Report released June 2013 Cover photo by TechnoServe Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Background a. Incubators and Accelerators in Traditional Business Sectors b. Incubators and Accelerators in the Impact Investing Sector III. Data and Methodology IV. -

(I.) Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and The

(I.) MEČISLAV BORÁK (Czech Republic) The main features of occupation policy in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the rest of Protectorate of the Czech Lands Bohemia and When Nazi German troops occupied the interior of the Czech Lands in March 1939, the invasion marked the beginning of over six years of occupation which would last until the final days of the Second World War in Europe. On Moravia and the basis of a decree issued by Hitler, the occupying authorities established an entity named the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; however, despite its proclaimed autonomy, the Protectorate was in fact entirely controlled by the post-war the German Reich, and the Reich’s actions proved decisive for the fate of the Czech nation. When researching this period, however, we should not neglect the fact that there were other parts of the Czech Lands which lay outside development of the the Protectorate throughout the war, as the Nazis had seized them from Czechoslovakia in the autumn of 1938, before the invasion of what remained of the country. This seizure was a consequence of the Munich Agreement, State – historical which enabled Nazi Germany to annex the border areas in the historical provinces of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia; the Agreement was forced upon the Czechoslovak Republic, and ultimately led to the state’s disintegration overview and demise. In September 1939 the Polish-occupied part of Těšín (Teschen/ Cieszyn) Silesia were taken by Germany; from this point on, the entire territory of the Czech Lands (both the border regions and the interior) came under the direct control of the Third Reich. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

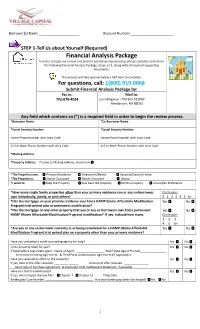

Financial Analysis Package in Order to Begin Our Review and Prevent Any Delays in Processing, Please Complete and Return

Borrower(s) Name Account Number STEP 1-Tell Us about Yourself (Required) Financial Analysis Package In order to begin our review and prevent any delays in processing, please complete and return the following Financial Analysis Package, Steps 1-11, along with all required supporting documents. This process will take approximately a half hour to complete. For questions, call: 1(800) 919-0068 Submit Financial Analysis Package by: Fax to: Mail to: 702-670-4024 Loss Mitigation – PO Box 531667 Henderson, NV 89053 Any field which contains an (*) is a required field in order to begin the review process. *Borrower Name *Co-Borrower Name *Social Security Number *Social Security Number Home Phone Number with Area Code Home Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code *Mailing Address *Property Address If same as Mailing Address, check here *The Property is my: Primary Residence Investment/Rental Seasonal/Second Home *The Property is: Owner Occupied Renter Occupied Vacant *I want to: Keep the Property Give back the property Sell the property Unsure/No Preference *How many single family properties other than your primary residence you or any co-borrowers Circle one: own individually, jointly, or with others? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6+ *Has the mortgage on your primary residence ever had a HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Yes No Program) trial period plan or permanent modification? *Has the mortgage on any other property that you or any co-borrowers own had a permanent Yes No HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Program) modification? If yes, indicate how many. -

Town Charter

TABLE OF CONTENTS (The Table of Contents is not part of the official Charter. Editorially provided as a convenience) PREAMBLE 1 ARTICLE ONE - POWERS OF THE TOWN 1 Section 1 Incorporation 1 Section 2 Form of government and title 1 Section 3 Scope and interpretation of town powers 1 Section 4 Intergovernmental cooperations 1 ARTICLE TWO - THE TOWN COUNCIL 2 Section 1 Composition and membership 2 Section 2 Eligibility 2 Section 3 Chairman, Vice Chairman and Clerk 2 Section 4 General powers and duties 3 Section 5 Procedures 3 Section 6 Town bylaws 4 Section 7 Action requiring a bylaw 4 Section 8 Vacancy 5 ARTICLE THREE - ELECTED TOWN BOARDS AND OFFICERS 5 Section 1 General provisions 5 Section 2 Special Provisions 5 Section 3 Vacancies 6 ARTICLE FOUR - THE TOWN ADMINISTRATOR 6 Section 1 Appointment and qualifications 6 Section 2 Powers and duties 7 Section 3 Removal of the Town Administrator 8 Section 4 Acting Town Administrator 8 ARTICLE FIVE - TOWN ELECTIONS 9 Section 1 Biennial Town Election 9 Section 2 Initiative 9 Section 3 Referendum 10 Section 4 Recall of elective officers 11 ARTICLE SIX - FINANCIAL PROVISIONS AND PROCEDURES 12 Section 1 Applicability of general law 12 Section 2 Finance Committee 12 Section 3 Submission of budget and budget message 12 Section 4 Budget message 13 Section 5 Budget Proposal 13 Section 6 Action on the proposed budget 13 Section 7 Capital improvements program 14 Section 8 Emergency appropriations 14 ARTICLE SEVEN - GENERAL PROVISIONS 14 Section 1 Charter amendment 14 Section 2 Specific provisions to prevail 14 Section 3 Severability of Charter 15 page \* romani Section 4 Town boards, commissions and committees 15 Section 5 Counting of days 15 Section 6 Phasing of terms 15 Editor's Note: Former Section 7, Suspensions and removals, which immediately followed and was comprised of Sections 7-7-1 through 7-7-5, was repealed by Ch. -

Conflicts-In-Federal-Systems-Mintz

PUBLICATIONS SPP Research Paper Volume 12:14 April 2019 TWO DIFFERENT CONFLICTS IN FEDERAL SYSTEMS: AN APPLICATION TO CANADA*† Jack M. Mintz SUMMARY Canadians are used to taking seriously the threat of separation when it comes to Quebec, but a more serious, less manageable form of conflict may eventually emerge in the federation between Western Canada and the rest of Canada. Where the Canadian government has been successful so far in managing the “conflict of taste” that has led to Quebec’s historic discomfort in the Canadian federation, because the federal government possesses the tools to address that challenge, it does not have the same tools to manage the “conflict of claim” that is creating increased dissatisfaction with Confederation in the West. The result is that Canada is a less stable federation than many observers realize. Interestingly, the future of its unity depends largely on whether the West is able to establish a lasting political alliance with Ontario even though that would mean Quebec no longer being critical for national coalitions. Conflicts of taste revolve around differences in political preferences between regions within a federation. While Quebec is animated by its different culture, history and language than the rest of Canada, which has created a conflict of taste, mechanisms have been put in place to help mitigate the friction, including: Provincial powers over key cultural institutions such as education and health, special fiscal and immigration arrangements for Quebec, guaranteed bilingualism in federal institutions and tax-collection powers unique to Quebec. Quebec’s ability to wield federal power through a Central Canadian alliance with Ontario has also helped partially alleviate the province’s discomfort within Confederation. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Wharton Borough Figure 1: Preservation Area

Borough of Wharton Highlands Environmental Resource Inventory Figure 1: Preservation Area Rockaway Township Jefferson Township Roxbury Township Wharton Borough Dover Town Mine Hill Township Preservation Area Wharton Borough Municipal Boundaries 1 inch = 0.239 miles $ September 2011 Borough of Wharton Highlands Environmental Resource Inventory Figure 2: Land Use Capability Map Zones Rockaway Township Jefferson Township Roxbury Township Wharton Borough Dover Town Mine Hill Township Regional Master Plan Overlay Zone Designation Zone Wharton Borough Protection Lakes Greater Than 10 acres Conservation Preservation Area Existing Community Municipal Boundaries 1 inch = 0.239 miles Sub-Zone Existing Community Environmentally Constrained Conservation Environmentally Constrained Lake Community $ Wildlife Management September 2011 Borough of Wharton Highlands Environmental Resource Inventory Figure 3: HUC 14 Boundaries Rockaway Township 02030103030040 Rockaway R Jefferson Township 02030103030060 Green Pond Brook Roxbury Township Wharton Borough 02030103030070 Rockaway R Dover Town Mine Hill Township HUC 14 Subwatersheds Wharton Borough Stream Centerlines 1 inch = 0.239 miles Preservation Area Municipal Boundaries $ September 2011 Borough of Wharton Highlands Environmental Resource Inventory Figure 4: Forest Resource Area Rockaway Township Jefferson Township Roxbury Township Wharton Borough Dover Town Mine Hill Township Forest Resource Area Wharton Borough Preservation Area Municipal Boundaries 1 inch = 0.239 miles $ September 2011 Borough of Wharton -

Municipal Monitor Program

MUNICIPAL MONITOR PROGRAM GREATER BOSTON ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS® About the Municipal Monitor Program The goal of the Municipal Monitor Program is to increase member involvement in association government affairs programs, build relationships between members and local municipal leaders, and develop an early tracking system to identify and address issues of concern. The program positions REALTORS® to have a direct impact on local decisions affecting real estate and private property rights and places the REALTOR® Association in the forefront as a defender of private property rights. Who are Municipal Monitors? Municipal Monitors are the key players that connect Local REALTOR® Associations to the municipalities and communities they serve. A Municipal Monitor is expected to keep track of those issues related to real estate and private property rights affecting his or her community that are consistent with the Association’s public policy statement. Examples of the duties of a Municipal Monitor a: Identify and monitor real estate related issues in his or her town or city of residence or business by engaging in the following activities: Maintain contact with local officials and committees; Attend any relevant public meetings for local committees such as Zoning Board of Appeals, Planning Board, or Annual Town Meeting; Monitor local media outlets for news and updates on issues; and Report to their local Government Affairs Committee or Local Association with any updates. Advocate on behalf of all REALTORS®; Attend local REALTOR® Association legislative events and REALTOR® Day on Beacon Hill; Sign and return this pledge. Municipal monitors are not expected to develop talking points or present testimony at a municipal committee meeting, but may do so if willing. -

52 - the Enclaves and Counter-Enclaves of Baarle (B/NL) by Frank Jacobs December 12, 2006, 1:04 PM

52 - The Enclaves and Counter-enclaves of Baarle (B/NL) by Frank Jacobs December 12, 2006, 1:04 PM One of the unlikeliest complexes of enclaves and exclaves in the world is to be found on the Belgian-Dutch border, and is centred on Baarle. This town, while surrounded entirely by Dutch territory, consists of two separate administrative units, one of which is the Dutch commune of Baarle-Nassau, the other being the Belgian commune of Baarle-Hertog.For an exhaustive history, please visit this page of the Buffalo Ontology Site. That same story, more succinctly: here… The Belgian-Dutch border was established in the Maastricht Treaty of 1843, which mostly confirmed boundaries which were a few centuries old (as the separation of Belgium and the Netherlands has its origin in the religious wars of the 16th century). In the area around Baarle, it proved impossible to reach a definitive agreement. Instead, both governments opted to allocate nationality separately to each of the 5.732 parcels of land in the 50 km between border posts 214 and 215. These parcels ‘coagulated’ into a veritable archipelago of 20-odd Belgian exclaves in and around Baarle. In turn, some of these Belgian exclaves completely surround pieces of Dutch territory. Deliciously complicating this picture is a small enclave of Baarle-Nassau situated entirely within Belgium proper – and there’s even a Belgian parcel within a Dutch parcel within a Belgian enclave, which in turn is surrounded entirely by Dutch territory… Numerous attempts have been made throughout the centuries to (literally) rectify the situation, but they have obviously all failed – leaving the double entity of Baarle-Nassau/Baarle-Hertog with some absurd folklore. -

Town Charter

Taken from: Province of New Hampshire—Records of Council 1716 ( pages 690 & 691 ) Province of New Hampshire At a Council held at the Council chambers in Portsmouth March 14, 17151715----16161616 PRESENT: The Honorable George Vaughan, Esq., Lt. Governor; Richard Waldron, Samuel Penhallow, John Plaisted, Mark Hunking, John Wentworth, Esquires. Mr. Smith appeared at this Board on behalf of sundry inhabitants of Swampscott and presented a petition (against making Swampscott a town) as on file, bearing date, January 14, 1715-6*. Notwithstanding which petition and sundry other objections which have been made since ye first motions about making said Swampscott a town, it is In Council Ordered, that Swampscott Patent land be a township by the name of Stratham, and have full power to choose officers as other towns within this Province, and that the bounds of said town be according to the limits specified in a petition proffered to this board by Mr. Andrew Wiggin, the 13 th day of January last, except some families lying near to Greenland (viz.) John Hill, Thomas Leatherby, Enoch Barker, and Michael Hicks, which said some families shall belong to the Parish of Greenland: And that a meeting house be built on the King’s great road leading from Greenland to Exeter, within half a mile of the midway between ye bounds yet are next Exeter and the bounds that are next Greenland, as the road goes; and that they be obliged to have a learned orthodox minister to preach in said meeting house within one year from the date hereof. R. Waldron, Cleric Con.