Contractual Control in the Supply Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcome to the Carnegie Reporter

Volume 8 / Number 1 / Spring 2016 CARNEGIE REPORTER WELCOME TO THE Volume 8 / Number 1 / Spring 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS CARNEGIE REPORTER Chief Communications and Digital Strategies Officer Deanna Lee uclear annihilation. It’s a frightening, almost existential notion that many Director of Communications and Content Strategy of us—especially those born before or during the Cold War—have had Robert Nolan to consider at some point in our lives. Duck and cover drills and fallout Editor/Writer shelters, command and control procedures, the concept of mutually Kenneth C. Benson assured destruction—these once seemed to offer at least a veneer of Principal Designer Daniel Kitae Um security for Americans. But today’s nuclear threat has evolved and is somehow even more 06 14 N Researcher terrifying. As Carnegie Corporation President Vartan Gregorian writes in this issue of the Ronald Sexton Carnegie Reporter, “There is no longer a single proverbial ‘red phone’ in the event of a Production Assistant nuclear crisis.” Natalie Holt Carnegie Corporation of New York is a philanthropic foundation created by Nuclear security—and, more specifically, the threat of nuclear terrorism—was the Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to promote the subject of the fourth and final international Nuclear Security Summit organized by the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding among the people of White House in Washington, D.C., last March, and is a focus point in this issue of the United States. Subsequently, its charter the Corporation’s flagship publication. In addition to the president’s letter, we feature was amended to permit the use of funds for the same purposes in certain countries that a graphic novel-like retelling of the dramatic 2007 break-in at the Pelindaba Nuclear are or have been members of the British Overseas Commonwealth. -

Hillary Frileck Resume Updated

H HILLARY Phone 646-361-8682 F Email [email protected] LinkedIn linkedin.com/in/hillary-frileck FRILECK Website hillaryfrileck.com/ SENIOR ART & CONTENT PRODUCER PHOTOGRAPHY | ILLUSTRATION | INTEGRATED PRODUCTI ON | VIDEO PRODUCTION Innovative, creative art and content producer with over 20 years of experience in procuring quality content for client projects, including photography, illustration, and digital art. Subject Matter Expert Recognized for creative portfolio and an eye for talent. Highly respected and trusted for providing solutions to creative challenges, with ability to spot talent including those not initially considered. Keeps current on new trends and techniques in the art and production world. Captures and reflects the aesthetic concept in all design activities, working across all art mediums providing design, editorial, photographic, and video content, as well as developing and maintaining the visual identity of the Company. Client Management Builds, nurtures, and maintains exceptional relationships with art, photography, and illustration communities to realize the highest quality production. Able to effectively source artists for projects and negotiate production rates to create revenue opportunities. Solution-oriented with ability to anticipate and resolve issues, including last-minute changes due to location, talent, or weather issues by utilizing appropriate resources. Develops positive relationships with agents, artists, creative teams, and account teams. Leadership Resourceful, detailed-oriented, quick learner, and out-of-the-box thinker. Proven ability to work to strict deadlines in a fast- paced, rapidly changing environment. Effective communicator with exceptional presentation, negotiation, and influencing skills. Agile and adaptable leader able to operate in a fast-paced, rapidly changing, deadline-driven environment. Displays passion about the design vision for the company inspiring clients and other end users. -

ANTHONY GOICOLEA B

GOW LANGSFORD GALLERY ANTHONY GOICOLEA b. 1971, Cuba. Lives in New York, USA Although largely based in photography, Anthony Goicolea’s practice also includes drawing and video. Goi- colea gained international recognition in the late 1990s for his unsettling technique of arranging, within a single frame, photographic clones of himself in various poses. He has exhibited extensively in Europe and America, regularly in New Zealand since 2002, and in Asia. High- lights of his career include two recent solo exhibitions at La Galerie Particuliere in Paris (2013), the 2006 Cin- tas Fellowship, the 2005 BMW Photo Paris Award, as well as The Bronx Museum “Artist in the Market Place” program (1998), and the 1997 Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant. Goicolea’s art is held in numerous significant public collections, including MoMA; The Guggenheim Museum of Art, New York; The Brooklyn Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; and the Centro Galego De Arte Contemporanea, in Santiago De Compostela, Spain. Goicolea graduated from the Pratt Institute of Art with an MFA in sculpture and photography in 1996, and from The University of Georgia with a BFA in 1994 and BA in 1992, both with magna cum laude. Anthony Goicolea is a Cuban American artist based in New York. Gow Langsford Gallery has represented Goicolea since 2000. EDUCATION 1994-96 Pratt Institute of Art, MFA 1992-94 Sculpture; Minor, Photography 1989-92 The University of Georgia, BFA, Drawing and Painting, 1989 The University of Georgia, BA, Art History; Minor, Romance Languages SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Anonymous & Mohau Modisakeng // Passage, Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam 2015 HERE and ELSEWHERE: Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. -

ANTHONY GOICOLEA Education Born in Atlanta, GA, 1971 Lives and Works in New York

ANTHONY GOICOLEA Education Born in Atlanta, GA, 1971 Lives and works in New York. EDUCATION 1994–96 Pratt Institute of Art, MFA, Sculpture and Photography 1992–94 The University of Georgia, BFA, Drawing and Painting, Magna Cum Laude 1989–92 The University of Georgia, BA, Art History and Romance Languages, Magna Cum Laude 1989 La Universidad de Madrid SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013 Permanent marker, Ron Mandos Gallery, Amsterdam 2012 Alter Ego: A Decade of Work by Anthony Goicolea, 21c Museum, Louisville, KY (catalog) Anthony Goicolea, Galeria Senda, Barcelona, Spain 2011 Pathetic Fallacy, Postmasters Gallery, New York Alter Ego: A Decade of Work by Anthony Goicolea, NC Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC travelling to Telfair Museum, Savannah, GA (09/11-01/12) and 21c Museum, Louisville, KY (01/12 – 07/12) (catalog) Snowscape, Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA 2010 Related, Houston Center for Photography, Houston, TX DECEMBERMAY, ScheiblerMitte, Berlin Nailbiter, IKON Gallery, Birmingham UK Home, Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam 2009 Once Removed, Postmasters Gallery, New York MCA Denver, Photography Gallery, Denver, CO The Last Man Standing: Retrospective of Photography & Video works, Fireplace Project, East Hampton, NY 2008 Related III, Sandroni.Rey, Los Angeles Related II, Haunch of Venison, London Related I, Aurel Scheibler Gallery, Berlin Almost Safe, Monte Clark Gallery, Toronto 2007 The Septemberists, Sandroni Rey Gallery, Los Angeles Almost Safe Postmasters Gallery, New York The Septemberists, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, Korea (with Norbert Bisky and Martin Maloney) Haunch of Venison, Zürich, Schweiz (with Mat Collishaw) 2006 The Septemberists, Aurel Scheibler Gallery, Berlin Monte Clark Gallery, Toronto, Canada Monte Clark Gallery, Vancouver, Canada Drawings, Sandroni Rey Gallery, Los Angeles 2005 Louis Adelatando Gallery, Miami Estaciones, Galeria Luis Adelantado, Valencia, Spain. -

ANTHONY GOICOLEA Education Born in 1971

ANTHONY GOICOLEA Education Born in 1971. Lives and Works in New York. Education Pratt Institute of Art, MFA, Sculpture; Minor, Photography, 1994–96 The University of Georgia, BFA, Drawing and Painting, magna cum laude, 1992–94 The University of Georgia, BA, Art History; Minor, Romance Languages, magna cum laude, 1989– 92 La Universidad de Madrid, 1989 Solo Exhibitions 2007 ALMOST SAFE Postmasters Gallery, New York 2006 THE SEPTEMBERISTS Aurel Scheibler Gallery, Berlin Monte Clark Gallery, Toronto, Canada Monte Clark Gallery, Vancouver, Canada DRAWINGS Sandroni Rey Gallery, Los Angeles 2005 Louis Adelatando Gallery, Miami Estaciones, Galeria Luis Adelantado, Valencia, Spain. OUTSIDERS - Videos and Photographs by Anthony Goicolea, Cheekwood Museum of Art Museum, Nashville, TN SHELTERED LIFE, New Drawings, Photographs and Video Installation, Postmasters Gallery, New York Anthony Goicolea, Photographs, Drawings and Video: The Arizona State University Museum of Art, Tempe, AZ 2004 SHELTERED LIFE, New Drawings, Photographs and Video Installation, Galerie Aurel Scheibler Cologne, Germany KIDNAP, New Drawings, Photographs and Video Installation, Sandroni-Rey Gallery, Los Angeles, CA KIDNAP, New Drawings, Photographs and Video Installation, Torch Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands TEA PARTY, New Video Installation, Madison Avenue Calvin Klein Space, New York, NY Anthony Goicolea, New Videos, Spazio-(H), Milan, Italy Recent Works, New Photographs, Angstrom Gallery, Dallas, TX Boys Will Be Boys, The John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI, -

Ralph's Tougher Targets/2 Economy Pinches Legwear/10

RALPH’S TOUGHER TARGETS/2 ECONOMY PINCHES LEGWEAR/10 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’MONDAY Daily Newspaper • July 28, 2008 • $2.00 Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear Fashion’s First Aid Kit WHAT WORKS IN THE TOUGHEST TIMES — times like now? WWD interviewed more than 30 business experts, industry leaders, veterans and academics for their advice on how fashion companies can survive, strengthen and push toward a full recovery. Here, and on pages 16 to 24, the Fashion First Aid plan. 1 MANAGE COSTS 2 BE CONSERVATIVE WITH SALES 3 BE A LEADER 4 PROVIDE MORE VALUE 5 DELIVER CUSTOMER SERVICE 6 REALLOCATE SPACE 7 RETIME SHIPMENTS 8 EXPAND STRATEGICALLY 9 FOLLOW DEMOGRAPHICS 10 EXPLOIT TECHNOLOGY PHOTO BY VOLKER MOEHRKE/ZEFA/CORBIS PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, JULY 28, 2008 WWD.COM Chaiken to Leave New York By Julee Kaplan Francisco to work out of her headquarters at 116 WWDMONDAY haiken is done with New New Montgomery. She Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear CYork. will also look into joining Julie Chaiken, chief execu- a multi-line showroom FASHION tive offi cer, designer and owner in New York, in order Charming eyelets and classic gingham checks are among the novelties of the contemporary firm she to keep some sales pres- that give spring’s new lingerie a fresh girly appeal. founded in 1994, will close her ence there. She plans to 6 New York showroom next month show her collections in and move all operations to San New York during fashion GENERAL Francisco, where the company week, but will not have Business experts, industry leaders and academics offer advice on how is based. -

JOHNS HOPKINS MAGAZINE Have Your Cake

Sherlock Holmes, Hopkins Man p.14 The Butterfly’s Effects p.48 The 5/2 Diet p.21 The professor is already inspiring undergraduates in his acting and directing classes. JOHN ASTIN’S NEXT ACT But his true quest is to bring the theater major back to Johns Hopkins. p.28 VOLUME 64 NO. 2 SUMMER 2012 Once Quiet on the Western Front p.60 Idea The End Plan p.10 Der Blaue Jay p.73 JOHNS HOPKINS MAGAZINE Have your cake... Make a gift to Johns Hopkins now. Receive income for life. Live well and give back to Johns Hopkins with a Charitable Gift Annuity. Fund a Charitable Gift Annuity with a minimum gift of $10,000 (cash or appreciated securities) and enjoy the following benets: t Guaranteed, xed payments for life to you and/or a loved one t Partially tax-free income t Immediate charitable deduction for a portion of the gift t Favorable treatment of capital gains, if donated asset is appreciated securities t Satisfaction of knowing you are making a lasting contribution to the mission of JHU Charitable Gift Annuity Rates Calculate your benefits at as of January 1, 2012 giving.jhu.edu/giftplanning Age One-life rate To request a personalized illustration 90 9.0% or learn more, please contact: 85 7.8% 80 6.8% Johns Hopkins Oce of Gift Planning 75 5.8% 410-516-7954 or 800-548-1268 70 5.1% [email protected] 65 4.7% giving.jhu.edu/giftplanning Seek advice from a tax professional before entering into a gift annuity agreement. -

Annual Report08.Pdf

Creating Excellence 2007–08 ANNUAL REPORT 2 The Culinary Institute of America 2008 Message from the Chairman and the President 5 Changing Lives 6 Advancing Knowledge 12 Shaping the Industry 18 Financial Highlights 26 Board of Trustees 30 In Memoriam 33 The Society of Fellows 34 Investing in the Future 36 Our Benefactors 38 New Pledges 38 Honor Roll 38 Society of the Millennium 40 Corporations and Organizations 40 Parents and Friends 41 Alumni 45 Faculty and Staff 48 Gifts Made in Memory 48 Gifts Made in Honor 51 Donor Advised Funds 51 Named Facilities at the CIA 52 OUR MISSION The Culinary Institute of America is a private, not-for-profit college dedicated to providing the world’s best professional culinary education. Ex- cellence, leadership, professionalism, ethics, and respect for diversity are the core values that guide our efforts. We teach our students the general knowledge and specific skills necessary to live successful lives and to grow into positions of influence and leadership in their chosen profession. This annual report, covering Fiscal Year June 1, 2007 through May 31, 2008, was submitted at the Annual Meeting of the Corporation of The Culinary Institute of America on October 25, 2008. ©2008 The Culinary Institute of America Photography: Mary Koniz Arnold, Bill Denison, Faith Echtermeyer, Keith Ferris, Steve LaBadessa, Mark Langford, Terrence McCarthy, and Christian Witkin Back Cover Illustration: Beverley Colgan The Culinary Institute of America, 1946 Campus Drive, Hyde Park, NY 12538-1499 • 845-452-9600 • www.ciachef.edu The CIA at Greystone and the CIA, San Antonio are branches of the CIA, Hyde Park, NY. -

Lowbrow Art : the Unlikely Defender of Art History's Tradition Joseph R

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2013 Lowbrow art : the unlikely defender of art history's tradition Joseph R. Givens Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Givens, Joseph R., "Lowbrow art : the unlikely defender of art history's tradition" (2013). LSU Master's Theses. 654. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/654 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOWBROW ART: THE UNLIKELY DEFENDER OF ART HISTORY’S TRADITION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Joseph R. Givens M.S., Arkansas State University, 2005 May 2013 I dedicate this work to my late twin brother Joshua Givens. Our shared love of comics, creative endeavors, and mischievous hijinks certainly influenced my love of Lowbrow Art. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professor Darius Spieth. Without his open mind and intellectual guidance, a thesis on this marginalized movement would not have been possible. I want to express my gratitude to Robert and Suzanne Williams who have patiently answered all of my inquiries without hesitation. -

Resumé / CV . Gwendolyn Witkin . [email protected] Phone: +31 (0) 6 11 520 350

Resumé / CV . Gwendolyn Witkin . [email protected] Phone: +31 (0) 6 11 520 350 . http://www.gwendolynwitkin.com Art direction / Set styling for Photography All categories for photography are listed in alphabetical order Photographer Print Client Editorial Alique Bacardi Aarp Bullitin Andric Bank of America Blackbook Magazine Ben Baker Bijenkorf Fortune Magazine Arthur Belebeau Campbell Elle Korea Paul Bellaart Centocor Glamour Magazine Augusta Butera Elizabeth and James Gourmet Magazine Marlena Belinska Lens Crafters Inspiration Magazine Juliette Bongers Levi's Linda Jouke Bos L'Oréal L'Official (Brazil) Levi Brown Mc Donalds Maxim Magazine Wendelien Daan Nuts Men's Health Marc de Groot Nokia Ocean Drive Carly Hermes Philips Oprah Magazine Frans Jansen Ray Ban Prevention Magazine Naomi Kaltman Reclas Time Magazine Caroline Knopf Reebok Vanity Fair (Italy) Sergio Kurhajec Ruinart Vegas Magazine Micheal Lewis Samson Vibe Magazine Michelle Pedone Samsung Vivre Magazine Kate Powers Target Vogue NL Yani Van Gils Vogue US Yossi Michaelli Winston Tiago Molinos Krista van der Niet Sophie van der Perre Philip Riches Thomas Rush Hyungwo Ryoo Gian Andrea di Stefano Mark Stetler Mario Testino Oof Verschuren Valentina Vos Christian Witkin David Yellen Harry de Zitter Production Design for Commercials Horizontal order Director Commercial Production Company Yousef Eldin Absolut Vodka UK Fat Fred Jeroen Mol Basic Fit Fat Fred Silivan Hooglander Cozy & Trendy Shut Up & Shoot Films Hiba Vink FBTO State31 Bram van Alphen Pickwick Caviar Mike van Diem Gall & Gall 25 fps Reynald Gessel Johnson & Johnson Caviar Paul Ruigrok ABN AMRO Caviar Bram van Alphen Ikea, 4 commercials Caviar Todd Broder Kraft Broderville Pictures, NYC, US Mark Richardson Operation Fuel, 3 spots. -

They Don’T Care...’ SPORTS 23 Philanthropy Vote Fails Again with MSG NEWS 4

College could have off Martin Luther King, Jr. Day in 2008-09 NEWS 7 Dr. Seuss-based show opens Jan. 25 and runs until Jan. 27 in the PAC A&E 16 One sheep, two sheep, three sheep, four...Tips on how to catch up on sleep FEATURES 15 Hepfi nger is certainly not an ‘Average Joe.’ Read all about the ’Hurst icon SPORTS 26 Also inside OPINION 19 COMIC 20 ‘They don’t care...’ SPORTS 23 Philanthropy vote fails again with MSG NEWS 4 Available online: merciad.mercyhurst.edu Plumbing issues force change in senior gift 2 PAGE 2 NEWS Jan. 23, 2008 Change of plans for senior gift By Casey Greene Managing editor The Mercyhurst College Senior Gift Steering Committee has had to decide on a new location for the senior class gift. The original idea for the gift has remained, but the location has been changed. “The concept of a 24-hour lounge has not changed,” said Director of the Senior Gift, Cathy Anderson. “Instead of being on the main fl oor of the library, the lounge will now be located on the lower level.” Steering Committee member senior Jeff Allen said the new location will face the north lawn, which overlooks East 38th Street. The location change was nec- essary due to issues with the location of sanitary pipes, said Anderson. Shortly after deciding upon the original location of the lounge, Mercyhurst College administra- tors found that the sanitary pipes needed to create a restroom were located on the east side of the building, not the west side, as proposed in the original plan. -

Issue-17.Pdf

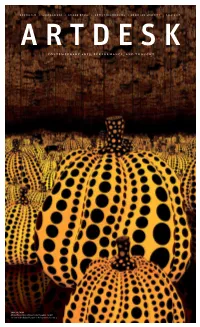

BRUTALISM / GUADALAJARA / EILEEN MYLES / ARTIST RESIDENCIES / AMERICAN GRAFFITI FALL 2017 CONTEMPORARY ARTS, PERFORMANCE, AND THOUGHT YAYOI KUSAMA All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins (2016) On view at the Dallas Museum of Art beginning October 1. WHITE RUSSIAN Pour vodka and coffee liqueur (two to one) over plentiful ice. Add a splash of butterscotch schnapps (trust us), top with heavy cream. Take 'er easy, Dude. FALL 2017 Brute Force FEW ARCHITECTURAL STYLES have been as misunderstood and even despised as Brutalism. Often incorporating concrete in bold monolithic designs, the style came into vogue during the turbulent 1960s and 1970s—a physical manifestation of institutional strength and order amid the chaos of the era. Indeed, many Brutalist buildings were constructed as governmental housing, libraries, offices, and schools, which may be why several of them were used as locations for films with dystopic, futuristic themes. By the 1980s, the stark edginess of Brutalism seemed out of place amid the glitz and glitter of the “greed is good” decade. Over-the-top, ornamental postmodernism became the architectural darling of the day, and many Brutalist relics were maligned as ugly, imposing, and austere. Recently, the style has started to be re-evaluated by scholars, architects, and the public, just as many of the finest examples of Brutalism have been threatened with demolition. Other Brutalist icons have been restored and are appreciated anew for their sculptural elegance. BY LYNNE ROSTOCHIL PYRAMID SCHEME In the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination, Dallas mayor Erik Jonsson sought to combat the “City of Hate” moniker the city had acquired.