Papers on Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

Scangate Document

P lu n g in g 5 into politics Should sports stars dive in? When you consider what makes a successful politician, three things stand out: to succeed, a politician must be reasonably popular, they should have a fairly high profile, and most important of all, they have to be credible. If that’s basically what it takes, there’s a select band of Australians boots. "Some translate their public standing into lucrative who have all the right qualifications in spades - Australia’s top sponsorship deals, or a career as a commentator," she says. sports people. Jackie Kelly says sitting politicians are lucky that more elite sports Most of our best sportsmen and women boast the sort of profile people don’t attempt to win seats in Parliament. “They’d do very and popularity a politician would kill for, and it seems everything a well,” she says, "at least initially. However, when they came to put sports star utters, no matter how banal, finds its way into the media. themselves up for a second term, they'd be assessed just like every other politician." It’s surprising then that so few of our top athletes have translated their public standing into a political career. The Member for the ACT seat of Fraser, Bob McMullan, has never represented his country in sport, but the Shadow Minister for There are some notable exceptions, among them cycling great Aboriginal Affairs is a self-confessed sports nut. He also knows what Sir Hubert Opperman who represented the seat of Corio in the political parties are looking for in their candidates, having served as House of Representatives between 1949 and 1967, and held an ALP State and National Secretary before entering Parliament. -

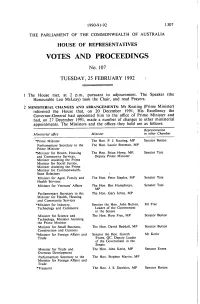

Votes and Proceedings

1990-91-92 1307 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 107 TUESDAY, 25 FEBRUARY 1992 1 The House met, at 2 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. The Speaker (the Honourable Leo McLeay) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Keating (Prime Minister) informed the House that, on 20 December 1991, His Excellency the Governor-General had appointed him to the office of Prime Minister and had, on 27 December 1991, made a number of changes to other ministerial appointments. The Ministers and the offices they hold are as follows: Representation Ministerial office Minister in other Chamber *Prime Minister The Hon. P. J. Keating, MP Senator Button Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Laurie Brereton, MP Prime Minister *Minister for Health, Housing The Hon. Brian Howe, MP, Senator Tate and Community Services, Deputy Prime Minister Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Social Justice, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Commonwealth- State Relations I Minister for Aged, Family and The Hon. Peter Staples, MP Senator Tate Health Services Minister for Veterans' Affairs The Hon. Ben Humphreys, Senator Tate MP Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Gary Johns, MP Minister for Health, Housing and Community Services *Minister for Industry, Senator the Hon. John Button, Mr Free Technology and Commerce Leader of the Government in the Senate Minister for Science and The Hon. Ross Free, MP Senator Button Technology, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister Minister for Small Business, The Hon. David Beddall, MP Senator Button Construction and Customs *Minister for Foreign Affairs and Senator the Hon. -

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution Or Black Hole?

Ministerial Staff Under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Author Tiernan, Anne-Maree Published 2005 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Department of Politics and Public Policy DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3587 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367746 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Ministerial Staff under the Howard Government: Problem, Solution or Black Hole? Anne-Maree Tiernan BA (Australian National University) BComm (Hons) (Griffith University) Department of Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2004 Abstract This thesis traces the development of the ministerial staffing system in Australian Commonwealth government from 1972 to the present. It explores four aspects of its contemporary operations that are potentially problematic. These are: the accountability of ministerial staff, their conduct and behaviour, the adequacy of current arrangements for managing and controlling the staff, and their fit within a Westminster-style political system. In the thirty years since its formal introduction by the Whitlam government, the ministerial staffing system has evolved to become a powerful new political institution within the Australian core executive. Its growing importance is reflected in the significant growth in ministerial staff numbers, in their increasing seniority and status, and in the progressive expansion of their role and influence. There is now broad acceptance that ministerial staff play necessary and legitimate roles, assisting overloaded ministers to cope with the unrelenting demands of their jobs. However, recent controversies involving ministerial staff indicate that concerns persist about their accountability, about their role and conduct, and about their impact on the system of advice and support to ministers and prime ministers. -

The Most Vitriolic Parliament

THE MOST VITRIOLIC PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE OF THE VITRIOLIC NATURE OF THE 43 RD PARLIAMENT AND POTENTIAL CAUSES Nicolas Adams, 321 382 For Master of Arts (Research), June 2016 The University of Melbourne, School of Social and Political Sciences Supervisors: Prof. John Murphy, Dr. Scott Brenton i Abstract It has been suggested that the period of the Gillard government was the most vitriolic in recent political history. This impression has been formed by many commentators and actors, however very little quantitative data exists which either confirms or disproves this theory. Utilising an analysis of standing orders within the House of Representatives it was found that a relatively fair case can be made that the 43rd parliament was more vitriolic than any in the preceding two decades. This period in the data, however, was trumped by the first year of the Abbott government. Along with this conclusion the data showed that the cause of the vitriol during this period could not be narrowed to one specific driver. It can be seen that issues such as the minority government, style of opposition, gender and even to a certain extent the speakership would have all contributed to any mutation of the tone of debate. ii Declaration I declare that this thesis contains only my original work towards my Masters of Arts (Research) except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text to other material used. Equally this thesis is fewer than the maximum word limit as approved by the Research Higher Degrees Committee. iii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge my two supervisors, Prof. -

Ambassade De France En Australie – Service De Presse Et Information Site : Tél

Online Press review 17 March 2015 The articles in purple are not available online. Please contact the Press and Information Department. FRONT PAGE University reforms: U-turn fails to win over Senate (AUS) Martin, Lewis A LAST-DITCH compromise aimed at winning support for university fee deregulation will be voted down by the Senate tomorrow, leaving the future of tertiary funding in doubt. Malcolm Turnbull wears media backlash (AUS) Crowe A FIGHT over media reform is threatening to spark a new round of leadership talk within the federal government as Malcolm Turnbull battles criticism of policy ideas that were leaked against him before they were hammered out by cabinet. Metadata shift to protect sources (AUS) Crowe SECURITY agencies will have to seek court approval before checking on a journalist’s phone and internet records under a major government concession to secure the passage of new data retention laws by the end of this week. Silence from the Islands: grave concern for outlying villages smashed by Pam (AUS) McKenna The fate of thousands of people in Vanuatu - including scores of Australians - was last night still unknown, with communications down and rescuers struggling to get to many of the archipelago's islands in the wake of cyclone Pam. Abbott government's uni fee law headed for defeat despite major backdown (CAN+SMH) Knott The Abbott government's last-ditch bid to win support for its higher education reforms by abandoning a threat to sack 1700 scientists has failed to convince the Senate crossbench to support the deregulation of university fees. DOMESTIC AFFAIRS POLITICS Peta Credlin ‘conflict’ brawl escalates as texts leaked (AUS) Crowe THE key figure in the Liberal Party dispute over financial secrecy has escalated his calls for - action on a “conflict of interest” at the top of the party amid damaging leaks of his private criticism of Tony Abbott’s chief of staff, Peta Credlin. -

The Howard Government Success but Not Succession

The Sydney Institute Quarterly Issue 33, August 2008 immediately knew that his days as Treasurer were numbered. Not only had the Opposition replaced THE HOWARD Hayden with the extremely popular Hawke. But Fraser had lost what benefit there might have been in GOVERNMENT surprising Labor by calling an early election - the normal time for going to the polls would have been SUCCESS around October 1983. And so it came to pass that Hawke Labor comprehensively defeated the Coalition at the March BUT NOT 1993 election. The ALP polled 53.2 per cent of the total vote after the distribution of preferences - a SUCCESSION Labor record. Howard was devastated by the result. However, both in public and private, he registered pride in his wife’s evident wisdom and political Gerard Henderson acumen - in that she had anticipated Labor’s winning leadership change strategy to overturn some seven years of Coalition government. t seems that wisdom - just like beauty - frequently I resides in the eye of the beholder. Even when it HOWARD’S FATAL MISCALCULATION comes to the Liberal Party leadership. What was wise Around a quarter of a century later, Howard led the in, say, 1983 can be forgotten a quarter of a century later. Liberal Party to a devastating defeat - with Labor In 1983 John Howard told journalist Paul Kelly about attaining 52.7 per cent of the total vote after the how he learnt that Bob Hawke had replaced Bill distribution of preferences. This was the ALP’s second Hayden as Labor leader on the eve of the March 1983 highest vote ever - only exceeded by Hawke’s victory Federal election. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

The Prime Ministers' Partners

The Prime Ministers' Partners "A view is held, and sometimes expressed…that wives of Prime Ministers are more highly regarded and widely loved than Prime Ministers themselves, both during and after their terms of office." - Gough Whitlam "Tim Mathieson is the first bloke of Australia. We know this because he has a jacket to prove it." – Malcolm Farr, 2012 No. Prime Minister’s spouse Previous Partner of Children1 name 1. Jane (Jeanie) BARTON Ross Edmund BARTON 4 sons, 2 daughters 2. Elizabeth (Pattie) DEAKIN Browne Alfred DEAKIN 3 daughters 3. Ada WATSON Low Chris WATSON None 4. Florence (Flora) REID Brumby George REID 2 sons, 1 daughter 5. Margaret FISHER Irvine Andrew FISHER 5 sons, 1 daughter 6. Mary COOK Turner Joseph COOK 6 sons, 3 daughters 7. Mary HUGHES Campbell Billy HUGHES 1 daughter 8. Ethel BRUCE Anderson Stanley BRUCE None 9. Sarah SCULLIN McNamara Jim SCULLIN None 10. Enid LYONS Burnell Joseph LYONS 6 sons, 6 daughters 11. Ethel PAGE Blunt Earle PAGE 4 sons, 1 daughter 12. Pattie MENZIES Leckie Robert MENZIES 2 sons, 1 daughter 13. Ilma FADDEN Thornber Arthur FADDEN 2 sons, 2 daughters 14. Elsie CURTIN Needham John CURTIN 1 son, 1 daughter 15. Veronica (Vera) FORDE O’Reilley Frank FORDE 3 daughters, 1 son 16. Elizabeth CHIFLEY McKenzie Ben CHIFLEY None 17. (Dame) Zara HOLT Dickens Harold HOLT 3 sons 18. Bettina GORTON Brown John GORTON 2 sons, 1 daughter 19. Sonia McMAHON Hopkins William McMAHON 2 daughters, 1 son 20. Margaret WHITLAM Dovey Gough WHITLAM 3 sons, 1 daughter 21. Tamara (Tamie) FRASER Beggs Malcolm FRASER 2 sons, 2 daughters 22. -

Reinventing Political Institutions

Women, Pre-selection and Merit: Who Decides? Women, Pre-selection and Merit: Who Decides? Senator the Hon. Margaret Reynolds Many Australian women would assume that the greatest barrier to women’s participation in parliament is attracting sufficient votes to be elected. However, such reasoning ignores the reality of party political systems and the degree to which pre-selection of candidates is carefully controlled by the party power brokers, usually men. Pre-selection methods vary between and within parties, but the situation for women as candidates is comparable, in that the first hurdle to political representation is actually within the Australian party structure, where a dominant male culture still prevails, regardless of the fundamental and political ideology. The hurdles for women to gain election to legislative positions in Australia are mainly those that take place within ‘the secret garden of politics’— within party selectorate hierarchies…[which] tolerate the continuing advantages of incumbency for men.1 In 1977, a Labor candidate in New South Wales, Ann Conlon, described the landscape of political parties as that of tribal territory. She said: ‘Inside it the ruling group resides and rules, occasionally permitting certain outsiders the pleasure.’2 1 I. McAllister, Political Behaviour: Citizens, Parties and Elites in Australia, Longman, Melbourne, 1992, p.225. 2 A. Conlon, ‘"Women in Politics", A Personal Viewpoint’, The Australian Quarterly, September, 1977, vol.49, no.3, p.14. 31 Reinventing Political Institutions Certainly, the present gender imbalance in Australia’s federal and state parliamentary representation—since Australia led the way in women’s electoral reform—would seem to reinforce this view of women as ‘outsiders’ with no major political party having an enviable record in endorsing women candidates. -

Hon Penny Sharpe

NSW Legislative Council Hansard Page 1 of 3 NSW Legislative Council Hansard Rice Marketing Amendment (Prevention of National Competition Policy Penalties) Bill Extract from NSW Legislative Council Hansard and Papers Wednesday 16 November 2005. The Hon. PENNY SHARPE [5.43 p.m.] (Inaugural speech): I support the Rice Marketing Authority (Prevention of National Competition Council Penalties) Amendment Bill. As this is my first speech in this place I wish to formally acknowledge that we hold our deliberations on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. I pay my respects to elders past and present and to the Aboriginal people present here today. I thank the members of the House for their courtesy and indulgence as I take this opportunity to talk about the path that has brought me to this place, the values I have gained on the way, and what I hope to achieve as a member of Parliament. I joined the Labor Party when I was 19 for the very simple reason that I wanted to change the world— immediately. It is taking a little longer than I expected. But although I know now that commitment to change must be matched with patience and perseverance, I still believe in the principles and values I held as a young woman at her first Labor Party branch meeting. Australia is a nation of abundant wealth—in our environment, in our people, in our diversity and in our spirit. We are able to care for all of our citizens. That we do not is a burning injustice. I could not and cannot accept that in a wealthy nation like Australia we tolerate the poverty, the violence and the plain unfairness that too many Australians experience day after day.