Ontological Ambivalence in Jhumpa Lahiri's Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Super! Drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15Th

Super! drama TV December 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance from 1:00-7:00 on the 15th. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.11.30 2020.12.01 2020.12.02 2020.12.03 2020.12.04 2020.12.05 2020.12.06 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 MACGYVER Season 2 06:00 06:00 MACGYVER Season 3 06:00 BELOW THE SURFACE 06:00 #20 #21 #22 #23 #1 #8 [D] 「Skyscraper - Power」 「Wind + Water」 「UFO + Area 51」 「MacGyver + MacGyver」 「Improvise」 06:30 06:30 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #4 GENERATION Season 7 #7「The Grant Allocation Derivation」 #9 「The Citation Negation」 #11「The Paintball Scattering」 #13「The Confirmation Polarization」 「The Naked Time」 #15 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY 07:30 information [J] 07:30 「LOWER DECKS」 07:30 Season 12 Season 12 Season 12 #8「The Consummation Deviation」 #10「The VCR Illumination」 #12「The Propagation Proposition」 08:00 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 SUPERNATURAL Season 11 08:00 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #5 #6 #7 #8 Season 3 GENERATION Season 7 「Thin Lizzie」 「Our Little World」 「Plush」 「Just My Imagination」 #18「AVALANCHE」 #16 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO 「THINE OWN SELF」 08:30 -

Lord Jim Mythos of a Rock Icon Table of Contents

Lord Jim Mythos of a Rock Icon Table of Contents Prologue: So What? pp. 4-6 1) Lord Jim: Prelude pp. 7-8 2) Some Preliminary Definitions pp. 9-10 3) Lord Jim/The Beginning of the Morrison Myth pp. 11-16 4) Morrison as Media Manipulator/Mythmaker pp. 17-21 5) The Morrison Story pp. 18-24 6) The Morrison Mythos pp. 25-26 7) The Mythic Concert pp. 27-29 8) Jim Morrison’s Oedipal Complex pp. 30-36 9) The Rock Star as World Savior pp. 37-39 10) Morrison and Elvis: Rock ‘n’ Roll Mythology pp. 40-44 11) Trickster, Clown (Bozo), and Holy Fool pp. 45-50 12) The Lords of Rock and Euhemerism pp. 51-53 13) The Function of Myth in a Desacralized World: Eliade and Campbell pp. 54- 55 14) This is the End, Beautiful Friend pp. 56-60 15) Appendix A: The Gospel According to James D. Morrison pp. 61-64 15) Appendix B: Remember When We Were in Africa?/ pp. 65-71 The L.A. Woman Phenomenon 16) Appendix C: Paper Proposal pp. 72-73 Prologue: So What? Unfortunately, though I knew this would happen, it seems to me necessary to begin with a few words on why you should take the following seriously at all. An academic paper on rock and roll mythology? Aren’t rock stars all young delinquents, little more evolved than cavemen, who damage many an ear drum as they get paid buckets of money, dying after a few years of this from drug overdoses? What could a serious scholar ever possibly find useful or interesting here? Well, to some extent the stereotype holds true, just as most if not all stereotypes have a grain of truth to them; yet it is my studied belief that usually the rock artists who make the big time are sincere, intelligent, talented, and have a social conscience. -

Metaphors in Jhumpa Lahiri's Fiction

METAPHORS IN JHUMPA LAHIRI’S FICTION: A STUDY A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY MD SOHAIL AHMED Roll No. 06614105 DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY GUWAHATI GUWAHATI, INDIA August 2011 We have all come out of Gogol’s Overcoat Fyodor Dostoevsky TH-1053_06614105 Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Guwahati 781039 Assam, India DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “Metaphors in Jhumpa Lahiri’s Fiction: A Study” is the result of investigation carried out by me at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, under the supervision of Dr Liza Das and Prof Krishna Barua. The work has not been submitted either in whole or in part to any other university / institution for a research degree. Md Sohail Ahmed August 2011 IIT Guwahati TH-1053_06614105 Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Guwahati 781039 Assam, India CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Md Sohail Ahmed has prepared the thesis entitled “Metaphors in Jhumpa Lahiri’s Fiction: A Study” for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati. The work was carried out under our general supervision and in strict conformity with the rules laid down for the purpose. It is the result of his investigation and has not been submitted either in whole or in part to any other university / institution for a research degree. Liza Das Krishna Barua Supervisor Co-Supervisor August 2011 IIT Guwahati TH-1053_06614105 Preface and Acknowledgements The elegant, chiselled and to an extent tempered and understated prose through which Jhumpa Lahiri mostly paints varied shades of gray over her Bengali-American story worlds, has already earned her much popular and critical acclaim. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

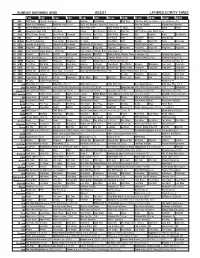

Sunday Morning Grid 8/22/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/22/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Graham Bull Riding PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf The Northern Trust, Final Round. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 AIG Women’s Open Final Round. (N) Race and Sports Mecum Auto Auctions 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Smile 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. 2021 Little League World Series 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse PiYo Accident? Home Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs AAA NeuroQ Grow Hair News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life MacKenzie-Childs Home MacKenzie-Childs Home Quantum Vacuum Å COVID Delta Safety: Isomers Skincare Å 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Great Scenic Railway Journeys: 150 Years Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Great Performances (TVG) Å 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Build a Better Memory Through Science (TVG) Country Pop Legends 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa MagBlue Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

Harpsichord and Its Discourses

Popular Music and Instrument Technology in an Electronic Age, 1960-1969 Farley Miller Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montréal April 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Ph.D. in Musicology © Farley Miller 2018 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... iv Résumé ..................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ vi Introduction | Popular Music and Instrument Technology in an Electronic Age ............................................................................................................................ 1 0.1: Project Overview .................................................................................................................. 1 0.1.1: Going Electric ................................................................................................................ 6 0.1.2: Encountering and Categorizing Technology .................................................................. 9 0.2: Literature Review and Theoretical Concerns ..................................................................... 16 0.2.1: Writing About Music and Technology ........................................................................ 16 0.2.2: The Theory of Affordances ......................................................................................... -

Strange Days: the American Media Debates the Doors, 1966-1971

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2015 Strange Days: The American Media Debates The Doors, 1966-1971 Maximillian F. Grascher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Grascher, Maximillian F., "Strange Days: The American Media Debates The Doors, 1966-1971" (2015). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 67. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/67 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Strange Days: The American Media Debates The Doors, 1966-1971 Maximillian F. Grascher 2 Introduction Throughout the course of American history, there have been several prominent social and political revolutions carried out by citizens dissatisfied with the existing American institutions run by the government and its civil servants. Of these revolutions, Vietnam War and civil rights protest among youth in the 1960s was of the most influential, shaping American society in the decades to come. With US involvement in Vietnam escalating and the call for African-American civil rights becoming more insistent by the year, thousands of America’s youth took to the streets to protest the country’s foreign and domestic policies and to challenge the US government, much to the anger of America’s older generations. Artists played a critical role in the unrest, including musicians who encouraged a reformation of American society’s established norms through revolution. -

CIRCUS February 1973

A 24520 IFEBRUARY 1973/ Z5', GREAT BRITAIN 30 PENCE 11 li Behind BLACK SABBATH'S U.S. Hatred La.,-/ Neil Young, America & FcompleteI if Joni Mitchell: 'Coast-To-Coast ■. 3 LPs From v? L CONCERT i California's L. Listings A r.. '''''''' ■” t A Hurricane ALICE r '/ji COOPER Hits Duane Allman: England The 26 LP's JAMES TAYLOR'S He Carly Courtship: Left ' What It Did For Behind One Man Dog' FREE COLOR ‘Flash In The Can' [MARC BOLAN And The Yes Dilemma I \Calendar Poster! Richard Thomas: The Waltons' 21-Year-Old Whiz Kid I i— ________ BUCKWHEAT - Buckwheat is Debbie Campbell, lead vocals and guitar; Bucky Smotherman, lead vocals and keyboards; Dub Campbell, lead guitar and electric violin; Mark Durham, bass and vocals; and Rick Gilbert, drums and percussion. Together they make some of the spunkiest, good-time rock'n’roll ” .) music around. You’ll hear a touch of blues, a little gospel, a trace of country, a bit of funk and a lot of fun in their music. Get Into the new Buckwheat LP “CHARADE” now and you’ll be into Buckwheat for a long time to come. DON’T MISS BUCKWHEAT LIVE AT CIN-A-ROCK V/ AT THE FOX THEATER IN ATLANTA, 'I NOVEMBER 29-DECEMBER 4. I AMPEX I 9TEAEO TAPtS J THE RECORD LOVERS GUIDE The mouth’s 24 most pungent LP’s . bite-sized reviews that sometimes bite back. THE PICK OF THE MONTH anas The one LP so powerful it should be played VOL. 7, No. 5 February, 1973 at a nuclear testing site. -

Musicians with Complex Racial Identifications in Mid-Twentieth Century American Society

“CASTLES MADE OF SAND”: MUSICIANS WITH COMPLEX RACIAL IDENTIFICATIONS IN MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN SOCIETY by Samuel F.H. Schaefer A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History Middle Tennessee State University December 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristine McCusker, Chair Dr. Brenden Martin To my grandparents and parents, for the values of love and empathy they passed on, the rich cultures and history to which they introduced me, for modeling the beauty of storytelling, and for the encouragement always to question. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For serving on my committee, encouraging me to follow my interests in the historical record, great patience, and for invaluable insights and guidance, I would like to thank Dr. Brenden Martin and especially Dr. Kristine McCusker, my advisor. I would also like to thank Dr. Thomas Bynum and Dr. Louis Woods for valuable feedback on early drafts of work that became part of this thesis and for facilitating wonderful classes with enlightening discussions. In addition, my sincere thanks are owed to Kelle Knight and Tracie Ingram for their assistance navigating the administrative requirements of graduate school and this thesis. For helpful feedback and encouragement of early ideas for this work, I thank Dr. Walter Johnson and Dr. Charles Shindo for their commentary at conferences put on by the Louisiana State University History Graduate Student Association, whom I also owe my gratitude for granting me a platform to exchange ideas with peers. In addition, I am grateful for the opportunities extended to me at the National Museum of African American Music, the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum, and the Center for Popular Music, which all greatly assisted in this work’s development. -

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal the Criterion: an International Journal in English ISSN: 0976-8165

About Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ Contact Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ Editorial Board: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal In English ISSN: 0976-8165 Bharati Mukherjee’s The Holder of the World: An Odyssey of Postcolonialism and Cultural Sensibility Anita Goswami Research Scholar, Dept. of English, H.N.B.Garhwal Central University, Srinagar Abstract: It is acknowledged that Bharati Mukherjee is an eminent diasporic writer of the third generation. She talks about the troubles of South Asian Women immigrants’ .In her novels female protagonists are the sufferer of identity crisis and they struggle on the ground of foreign land, east to west. In her novel The Holder of the World we see that Hannah Easton, female protagonist of the novel, she begins her journey from west to east but she not only searches her identity but also explores the various layers of multiculturalism. This novel is woven with threads of migration, immigration, historical evidence and transformation. The Holder of the World was published in 1993, deals with the story of a puritan woman named as Hannah Easton of seventeenth century. Later on she is known as ‘Salem Bibi’ an immigrant from America, who comes to India, absorbs herself in the Indian culture. Later on she becomes the mistress of Indian King Raja Singh Jadav. -

Dionysian Symbolism in the Music and Performance Practices of Jimi Hendrix

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2013 Dionysian Symbolism in the Music and Performance practices of Jimi Hendrix Christian Botta CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Dionysian Symbolism in the Music and Performance Practice of Jimi Hendrix Christian Botta Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Musicology At the City College of the City University of New York May 2013 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One – Hendrix at the Monterey Pop and Woodstock Festivals 12 Chapter Two – ‘The Hendrix Chord’ 26 Chapter Three – “Machine Gun” 51 Conclusion 77 Bibliography 81 i Dionysian Symbolism in the Music and Performance Practice of Jimi Hendrix Introduction Jimi Hendrix is considered by many to be the most innovative and influential electric guitarist in history. As a performer and musician, his resume is so complete that there is a tendency to sit back and marvel at it: virtuoso player, sonic innovator, hit songwriter, wild stage performer, outrageous dresser, sex symbol, and even sensitive guy. But there is also a tendency, possibly because of his overwhelming image, to fail to dig deeper into the music, as Rob Van der Bliek has pointed out.1 In this study, we will look at Hendrix’s music, his performance practice, and its relationship to the mythology that has grown up around him.