A LACK of GENDER DIVERSITY in the INDIAN JUDICIARY - Kairavi Raju*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

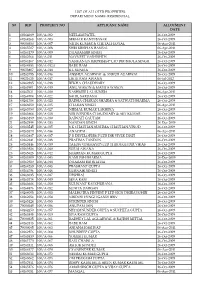

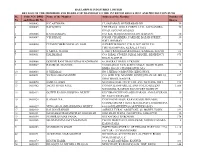

S# Rid Property No Applicant Name Allotment Date 1

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- RESIDENTIAL S# RID PROPERTY NO APPLICANT NAME ALLOTMENT DATE 1 60264689 100/A-002 NEELAM PATEL 26-Oct-2009 2 60264268 100/A-003 SEKHAR KANTI BASAK 26-Oct-2009 3 90000350 100/A-007 NITIN KUMAR & CHETALI GOYAL 06-Apr-2011 4 60265507 100/A-008 SHRI KRISHAN BANSAL 06-Apr-2011 5 60264179 100/A-009 DHARAMBIR SINGH 26-Oct-2009 6 60262564 100/A-011 NAVNEET VASHISHTH 26-Oct-2009 7 60264167 100/A-012 YASIKAN ENTERPRISES P LTD DIR BHOLA SINGH 26-Oct-2009 8 60264553 100/A-012A BABU RAM 26-Oct-2009 9 90023807 100/A-014 K L SUNEJA 26-Oct-2009 10 60265795 100/A-016 ANSHUL AGARWAL & ANKUR AGARWAL 26-Oct-2009 11 90021623 100/A-017 LIKHI RAM AWANA 06-Jul-2012 12 60262985 100/A-018 REKHA CHAUDHARY 26-Oct-2009 13 60263901 100/A-019 ANIL WASON & MAMTA WASON 26-Oct-2009 14 60267621 100/A-020 KASHMIRI LAL SUNEJA 06-Apr-2011 15 60264704 100/A-022 SAHIL SARDANA 26-Oct-2009 16 60261786 100/A-023 RADHA CHARAN SHARMA & SATWATI SHARMA 26-Oct-2009 17 60266050 100/A-025 CHARAN SINGH 06-Apr-2011 18 60263750 100/A-027 NIRMAL KUMAR LAKHINA 26-Oct-2009 19 60263868 100/A-028 VISHVENDRA CHAUDHARY & AJIT KUMAR 26-Oct-2009 20 60263189 100/A-030 RAJWATI GAUTAM 26-Oct-2009 21 60262994 100/A-033 NANDAN SINGH 26-Dec-2009 22 60263545 100/A-035 S K CHAUHAN,SUSHMA CHAUHAN,VINOD 26-Oct-2009 23 60265570 100/A-036 ANAGPAL 06-Apr-2011 24 60262887 100/A-037 P R DEVELOPERS P LTD DIR VIVEK DIXIT 26-Oct-2009 25 60262241 100/A-038 PRATIMA TANDON 26-Oct-2009 26 60263846 100/A-039 TALON VINIMAY(P) LTD THROUGH DIR.VIKAS 26-Oct-2009 27 60263926 100/A-040 -

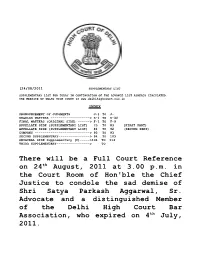

There Will Be a Full Court Reference on 24Th August, 2011 at 3.00 P.M. In

[24/08/2011 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS J-1 TO J- REGULAR MATTERS --------------------> R-1 TO R-30 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ------> F-1 TO F-9 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST) 75 TO 83 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST) 84 TO 92 (SECOND PART) COMPANY ----------------------------> 93 TO 93 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY----------------> 94 TO 103 ORIGINAL SIDE Supplementary (I)----->104 TO 114 THIRD SUPPLEMENTARY-----------------> TO There will be a Full Court Reference on 24th August, 2011 at 3.00 p.m. in the Court Room of Hon'ble the Chief Justice to condole the sad demise of Shri Satya Parkash Aggarwal, Sr. Advocate and a distinguished Member of the Delhi High Court Bar Association, who expired on 4th July, 2011. NOTES 1. MAC. Appeals of the year 2006 shall be listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice A.K. Sikri at 12.00 Noon on every Friday. 2. Hon'ble Mr. Justice Ajit Bharihoke will not be holding Court today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. 3. PC Act cases which were being listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice M.L. Mehta at 12.00 Noon on every Friday shall now be listed before Hon'ble Ms. Justice Mukta Gupta on every Friday. 4. MAC. Appeals of the year 2009 shall be listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice M.L.Mehta at 12.00 Noon on every Friday. CIRCULAR In continuation of Circular bearing F.No. -

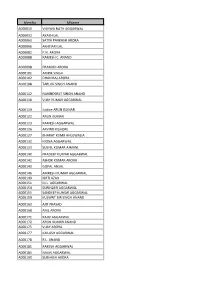

Memno Mname A000010 VISHWA NATH AGGARWAL A000032 AKASH LAL A000063 SATYA PARKASH ARORA A000066 AKHTIARI LAL A000082 P.N

MemNo MName A000010 VISHWA NATH AGGARWAL A000032 AKASH LAL A000063 SATYA PARKASH ARORA A000066 AKHTIARI LAL A000082 P.N. ARORA A000088 RAMESH C. ANAND A000098 PRAMOD ARORA A000101 AMRIK SINGH A000102 DHAN RAJ ARORA A000108 TARLOK SINGH ANAND A000112 NARINDERJIT SINGH ANAND A000118 VIJAY KUMAR AGGARWAL A000119 Justice ARUN KUMAR A000122 ARUN KUMAR A000123 RAMESH AGGARWAL A000126 ARVIND KISHORE A000127 BHARAT KUMR AHLUWALIA A000132 MONA AGGARWAL A000133 SUSHIL KUMAR AJMANI A000140 PRADEEP KUMAR AGGARWAL A000142 ASHOK KUMAR ARORA A000143 GOPAL ANSAL A000146 AMRESH KUMAR AGGARWAL A000149 KIRTI AZAD A000151 M.L. AGGARWAL A000154 SURINDER AGGARWAL A000155 SANDEEP KUMAR AGGARWAL A000159 KULWNT BIR SINGH ANAND A000163 AJIT PRASAD A000168 ANIL ARORA A000171 RAJIV AGGARWAL A000172 ARUN KUMAR ANAND A000175 VIJAY ARORA A000177 KAILASH AGGARWAL A000178 R.L. ANAND A000181 RAKESH AGGARWAL A000185 NALIN AGGARWAL A000190 SUBHASH ARORA A000192 A.K. DEV A000193 LALIT AHLUWALIA A000194 S.K. ARORA A000196 SUDHIR ARORA A000197 ASHOK KUMAR AHLUWALIA A000203 RAKESH ARORA A000204 SANTOSH AULUCK A000205 VINAY KUMAR ARORA A000207 AJIT SINGH A000211 ASHOK KUMAR A000212 L.M. AGGARWAL A000214 MADAN MOHAN AGGARWAL A000218 ASHOK ANAND A000223 JANAK RAJ ARORA A000226 DINESH AGNANI A000227 M.K. ARORA A000230 ASHOK KUMAR A000231 D.K. AGGARWAL A000236 RAM AVTAR AGGARWAL A000244 NAVEEN ANAND A000245 PARVEEN ANAND A000247 MADAN LAL ANAND A000250 JASPAl. S. ARORA A000251 ARVINDER SING ARORA A000253 MANJIT SINGH ARORA A000254 RAJPAL SINGH ARORA A000257 TRILOK NATH ANAND A000258 -

SUPPLEMENTARY LIST 1. Urgent Mentioning May

02.12.2014 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> J-1 TO 02 REGULAR MATTERS -----------------------> R-1 TO 55 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> F-1 TO 06 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 1 TO 79 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 80 TO 89 (FIRST PART) APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 90 TO 97 (SECOND PART) ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 98 TO 105 COMPANY ------------------------------> 106 TO 106 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> 107 TO NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 A.M. DELETIONS 1. C.M. 19630/2014in W.P.(C) 7284/2013 listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice Manmohan at item No.25 is deleted as the same is returned to Filing Counter. 2. W.P.(C) 6452/2014 listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice Suresh Kait at item No.12 is deleted as the same is a decided matter. 3. C.M.(M) 930/2012 listed before Hon'ble Mr. Justice Jayant Nath at item No.2 is deleted as the same is fixed for 02.02.2015. NOTICE The National Lok Adalat is to be held on 06th December, 2014(Saturday) in all the States of India. Accordingly, Delhi High Court Legal Services Committee is going to organize a National Lok Adalat with the approval of Hon'ble Mr. Justice Pradeep Nandrajog, Judge High Court of Delhi and Chairman, DHCLSC for the pending cases under following category:- 1. Misc. Appeals, Civil Appeals, 2nd Appeals, Original Suits, Writs,MACT Appeals. -

The Hazards of Smoking and the Benefits of Cessation: a Critical Summation of the Epidemiological Evidence in High-Income Countries Prabhat Jha*

REVIEW ARTICLE The hazards of smoking and the benefits of cessation: A critical summation of the epidemiological evidence in high-income countries Prabhat Jha* Centre for Global Health Research, Dalla Lana School of Public Health and Unity Health, Toronto, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada Abstract In high-income countries, the biggest cause of premature death, defined as death before 70 years, is smoking of manufactured cigarettes. Smoking-related disease was responsible for about 41 million deaths in the United States, United Kingdom and Canada, cumulatively, from 1960 to 2020. Every million cigarettes smoked leads to one death in the US and Canada, but slightly more than one death in the UK. The 21st century hazards reveal that smokers who start smoking early in adult life and do not quit lose a decade of life expectancy versus non-smokers. Cessation, particularly before age 40 years, yields large reductions in mortality risk. Up to two- thirds of deaths among smokers are avoidable at non-smoking death rates, and former smokers have about only a quarter of the excess risk of death compared to current smokers. The gap between scientific and popular understanding of smoking hazards is surprisingly large. Overview I summarize the causative role of smoking for the most common causes of death among adults in *For correspondence: high-income countries, drawing on data from Canada, the United States (US) and the United King- [email protected] dom (UK). The main objective of this analysis is to review the hazards of smoking and the benefits of cessation. I do so by examining the cause, nature and extent of tobacco-related diseases in high- Competing interest: See income countries between 1960 and 2020. -

C:\Users\A\Desktop\CPO Examinat

SI in CAPFs, ASI in CISF and SI in 9/12/2019 Delhi Police Examination-2019 (Paper-I) Shift 1 1. Which Commission was appointed by the central 8. Which of the following Indian cities is included government to examine issues related to Centre- in the list of 'UNESCO World Heritage Sites'? State relations? (a) Ahmedabad (b) Hyderabad (a) Mandal Commission (c) Murshidabad (d) Srinagar (b) Sarkaria Commission Ans-(a) (c) Nanavati Commission 9. Which mineral is popularly known as 'buried (d) Kothari Commission sunshine'? Ans-(b) (a) Iron (b) Bauxite 2. Which muscles in the skin contract to make the (c) Mica (d) Coal hairs on our skin stand up straight (goose bumps) Ans-(c) when we are cold or frightened ? 10. What is the primary function of the eccrine (a) Elastin (b) Epidermis glands? (c) Collagen (d) Arrector pili (a) To produce sweat Ans-(d) (b) To produce colour of the skin 3. In which year was the first-ever motion to (c) To produce body hair remove a Supreme Court Justice signed, by 108 (d) To produce growth hormones members of the Parliament? Ans-(a) (a) 1984 (b) 1991 11. Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker are two architects credited to have designed the city of: (c) 1978 (d) 1996 (a) Allahabad (Prayagraj) Ans-(b) (b) Chandigarh 4. Which of the following is the outer layer of the (c) Raipur Earth that is made of plates which fit together (d) New Delhi like a jigsaw puzzle? Ans-(d) (a) Lithosphere (b) Biosphere 12. The 'Hemis Tsechu' festival commemorates the (c) Mesosphere (d) Asthenosphere birth anniversary of: Ans-(a) (a) Dalai Lama 5. -

Paper-I) Roll Number

SI in CAPFs, ASI in CISF and SI in Delhi Police Examination-2019 (Paper-I) Roll Number Candidate Name Exam iON Digital Zone iDZ Trinity 1Shri Jairam Education Venue Society Kokta Bypass Road. Exam Date 12/12/2019 Exam Time 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM Subject SI CPO Examination 2019 SectionQ.1 : General Intelligence and Reasoning Ans 1. 2. 3. 4. Question ID : 864407917 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 1 Q.2 In a certain code language, ‘REQUEST’ is written as ‘22-21-7-23-19-7-20’. How will ‘SWITCH’ be written as in that language? Ans 1. 21-25-11-22-5-10 2. 19-23-11-22-5-8 3. 10-5-20-11-25-21 4. 10-5-22-11-25-21 Question ID : 864407892 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 2 Q.3 examscomp.com Ans 1. 2. 3. 4. Question ID : 864407913 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 3 Q.4 Ans 1. 2. examscomp.com 3. 4. Question ID : 864407918 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 2 Q.5 Ans 1. 2. 3. 4. Question ID : 864407922 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 1 Q.6 Select the option that will fill in the blank and complete the given series. 7, 16, 40, 84, _____, 252 Ans 1. 151 examscomp.com 2. 149 3. 150 4. 153 Question ID : 864407897 Status : Answered Chosen Option : 3 Q.7 Select the option that is related to the third term in the same way as the second term is related to the first term. HOSPITAL : JLWKOMIC :: MEDICINE : ? Ans 1. OBHDIBVW 2. PBIHIBWV 3. PCHDIBWV 4. -

SL No. Folio NO./ DPID and Client ID No. Name of the Member Address of the Member Number of Shares 1 0000002 H C ASTHANA 17

BALLARPUR INDUSTRIES LIMITED DETAILS OF THE MEMBERS AND SHARE FOR TRANSFER TO THE INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND SL Folio NO./ DPID Name of the Member Address of the Member Number of No. and Client ID No. Shares 1 0000002 H C ASTHANA 17, SAIFABAD, HYDERABAD-DN. 30 2 0000003 RAFIQ BEG THE PRAGA TOOLS CORPN. LTD., ALEXANDRA 30 ROAD, SECUNDARABAD. 3 0000006 K M HAMEEDA C/O. K.B. MAQSOOD HUSSAIN, BADAUN, 30 4 0000007 V K DHAGE PODAR CHAMBERS, PARESEE BAZAR STREET, 30 FORT, BOMBAY 5 0000020 PUTHENCHERI GOPALAN NAIR SUPERINTENDENT, P.W.D. M.P. RETD P.O. 75 TIRUVEGAPPURA, KERALA STATE 6 0000029 S ABDUL WAHIB 5, OLD TRANQUEBAR STREET, KARIKAL, SOUTH 63 7 0000051 HALIMABAI C/O. IQBAL STORES, IQBAL MANZIL, RESIDENCY 975 ROAD, NAGPUR. 8 0000066 GOBIND RAM THAKURDAS WADHWANI 48, HAZRAT GANJ LUCKNOW. 3 9 0000067 RAMBHAU BANGDE C/O BHARATI SAW & RICE MILLS, EKORI WARD, 72 BINBA ROAD, CHANDRAPUR, M.S. 10 0000083 S J KHARAS NO.5,JEERA COMPOUND, KINGSWAY, 9 11 0000091 VATSALABAI MANDPE C/O. SHRI D.W. MANDPE, HINDUSTHAN OIL MILLS, 657 GHAT ROAD, NAGPUR. 12 0000098 SAMUEL JOHN NETURIA COAL CO./P/ LTD., P.O. NETURIA, DIST. 192 13 0000102 JAGJIT SINGH PAUL C/O.M/S. BANWARILAL AND CO LTD QUEENS 1,566 MANSIONS, BASTION ROAD FORT BOMBAY 14 0000122 GOTETI RADHA KRISHNA MURTY KUCHMANCHIVANI AGRAHARAM, AMALAPURAM, 30 DT. EAST GODAVARI. 15 0000124 K ANASUYA C/O P PATHU RAJU KEAVEKALKURGUMME 3 GUDDE,CIRCAR THOTA MACHLIPATTAM,KRISHNA 16 0000127 VENGARA RADHAKRISHNA MURTY 4-61/10 DILSHUKHNAGAR HYDERABAD 78 17 0000129 BALWANT SINGH AGRICULTURAL ASSISTANT, 85, MODEL TOWN, 192 18 0000131 GANGABAI MAHADEORAO JOGLEKAR JOGLEKAR WADA, GANJIPURA, JABALPUR. -

Unpaid Dividend As on 29.02.2020 Sl

RACL GEARTECH LIMITED -UNPAID DIVIDEND AS ON 29.02.2020 SL. FOLIO NO./DP ID & WARRANT NO OF PAYEE NAME PAYMENT INSTRU AMOUNT NO. CLIENT ID NO. SHARES _ VALUE_ MENT HELD DATE NO. 1 :0002466 :0000407 200 SABITA MOHAPATRA C/O MAJ R C 2-Dec-19 448920 200 MOHAPATRA 151 BASE HOSPITAL C/O 99 APO 000000 2 :0002605 :0000440 100 B SANTHA KUMARI ADVOCATE 86 2-Dec-19 448921 100 ANAYDA PURAM ST KUNNATHUR 638103 ERUDE DT T N 3 :0002636 :0000449 100 S SANKARAN 20/2903 SIVAN KUIL ST 2-Dec-19 448922 100 KARAMANA THIRUVANATHAPURAM 4 :0004141 :0000690 100 VINOD PRAKASH SRIVASTAVA V P 2-Dec-19 448923 100 SRIVASTAVA, CO I SO 2 (PERS) HQ CE (P) CHETAK (GREF) C/O 56 APO 5 :0006084 :0000953 100 MOHD MAQDUM SPL MT 2-Dec-19 448924 100 (COMMON) NO 2208 SQN AF C/O 56 APO 6 :0006648 :0001031 300 SUMITRA AGARWAL C/O 2-Dec-19 448925 300 CHOWDHURY BROTHERS PO PHUNTSHOLING BHUTAN 000000 7 :0007616 :0001176 100 V M SWAMI OLD NO.7, NEW NO.13 2-Dec-19 448926 100 4TH CROSS STREET SASTRI NAGAR CHENNAI 20 8 :0009559 :0001439 100 RAJESHWAR RANA C/O.COL.R K 2-Dec-19 448927 100 RANA 16 RAJ RIF C/O 56 APO 9 :0009561 :0001440 100 RAMESH KUMAR RANA LT.COL.R K 2-Dec-19 448928 100 RANA HQ 3 INF DIV C/O 56 APO 10 :0010299 :0001542 300 BHOLA SINGH LT COL BHOLA SINGH 2-Dec-19 448929 300 HEAD QUARTERS 22 INFANTRY DIVISION C/O. -

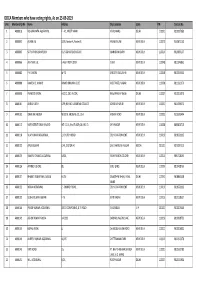

List of DDCA Members

DDCA Members who have voting rights, As on 25-09-2019 S.No. Membership No Name Address City/Location State PIN Contact No. 1 A000010 VISHWA NATH AGGARWAL F - 42 , PREET VIHAR VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 9810017950 2 A000032 AKASH LAL 1196, Sector-A, Pocket-B, VASANT KUNJ NEW DELHI 110070 9350872150 3 A000063 SATYA PARKASH ARORA 43, SIDDHARTA ENCLAVE MAHARANI BAGH NEW DELHI 110014 9810805137 4 A000066 AKHTIARI LAL S-435 FIRST FLOOR G K-II NEW DELHI 110048 9811046862 5 A000082 P.N. ARORA W-71 GREATER KAILASH-II NEW DELHI 110048 9810045651 6 A000088 RAMESH C. ANAND ANAND BHAWAN 5/20 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 9811031076 7 A000098 PRAMOD ARORA A-12/2, 2ND FLOOR, RANA PRATAP BAGH DELHI 110007 9810015876 8 A000101 AMRIK SINGH A-99, BEHIND LAXMI BAI COLLEGE ASHOK VIHAR-III NEW DELHI 110052 9811066073 9 A000102 DHAN RAJ ARORA M/S D.R. ARORA & C0, 19-A ANSARI ROAD NEW DELHI 110002 9313592494 10 A000112 NARINDERJIT SINGH ANAND WZ-111 A, IInd FLOOR,GALI NO. 5 SHIV NAGAR NEW DELHI 110058 9899829719 11 A000118 VIJAY KUMAR AGGARWAL 2, CHURCH ROAD DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 12 A000122 ARUN KUMAR C-49, SECTOR-41 GAUTAM BUDH NAGAR NOIDA 201301 9873097311 13 A000123 RAMESH CHAND AGGARWAL B-306, NEW FRIENDS COLONY NEW DELHI 110025 9891728293 14 A000126 ARVIND KISHORE 86, GOLF LINKS NEW DELHI 110003 9810418755 15 A000127 BHARAT KUMAR AHLUWALIA B-136 SWASTHYA VIHAR, VIKAS DELHI 110092 9818830138 MARG 16 A000132 MONA AGGARWAL 2 - CHURCH ROAD, DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 17 A000133 SUSHIL KUMAR AJMANI F-76 KIRTI NAGAR NEW DELHI 110015 9810128527 18 A000140 PRADIP KUMAR AGGARWAL DISCO COMPOUND, G.T. -

Indian Institute of Insurance Surveyors and Loss

INDIAN INSTITUTE OF INSURANCE SURVEYORS AND LOSS ASSESSORS (Promoted by IRDA, Govt. of India) Date: 21-06-2019 Dear Members, Update your email & mobile no: as the procedure decided for Central Council Election is through E- voting. Only one email & one mobile number will be entertained, if not updated only the first email & first mobile no available with iiisla database, which is uploaded along with this notice will be used for election purpose. If any changes in your email / mobile no: please write to [email protected] . Last date 28/06/2019 before 5:00PM. Issued by order of Election Officer Admin- IIISLA HO Regd. Office: 315,Paras Chambers,D.No.-3-5-890,HimayatNagar, Hyderabad-500029(T.S) e-mail : [email protected], [email protected], Web-site : www.iiisla.co.in., Telephone Numbers: 040- 66253666. S.No Name Membership No Mobile E-mail 1 Dinesh Chandra Agarwal F/W/00002 9414167183 [email protected] 2 Ravindra Bagga F/E/00003 9827161038 [email protected] 3 T.S.Shrinivaasan F/S/00005 9840022241 [email protected] 4 Rajendra Pershad Sharma F/W/00006 9821018703 [email protected] 5 Hari Mohan Walia F/N/00011 9717459555 [email protected] 6 P.Pandiyan F/S/00013 9841032566 [email protected] 7 Chinnakannu G F/S/00014 9443248231 [email protected] 8 T Panneerselvan F/S/00015 9443057484 [email protected] 9 Ashok Manohar Gawarikar F/W/00016 9820338650 [email protected] 10 Sandeep Bharti F/N/00020 9811093826 [email protected] 11 Gobind Ram Kejriwal F/N/00022 9811278129 [email protected] -

S No Name SLA License No. Memb No. Town / City Outstan Ding

SLA Outstan S No Name License Memb No. Town / City ding No. Balance 1 N Velayutham 72 F/S/00001 Chennai 0 2 Dinesh Chandra Agarwal 15798 F/W/00002 UDAIPUR 0 3 Ravindra Bagga 24906 F/E/00003 Durg -1500 4 T.S.Shrinivaasan 12645 F/S/00005 Chennai 0 5 Rajendra Pershad Sharma 739 F/W/00006 Mumbai 0 6 Koushik Roy 3445 F/E/00008 Kolkata 0 7 Hari Mohan Walia 1099 F/N/00011 Faridabad 0 8 P.Pandiyan 3385 F/S/00013 Chennai 0 9 Mehta K Ratilal 40071 A/W/00017 Vadodara 0 10 L G Ramachandran 1088 F/S/00019 Chennai 0 11 Sandeep Bharti 9169 F/N/00020 New Delhi 0 12 Gobind Ram Kejriwal 59743 F/N/00022 New Delhi 0 13 D Raghu Ram 17181 F/S/00023 Bangalore -2000 14 Sarjerao Y Patil 58396 F/W/00024 Kolhapur 0 15 Jasvinder Singh Josan 23385 F/N/00025 Chandigarh 0 16 Mohan Ramachandra Chabbi 15075 F/S/00028 Dharwad 0 17 Shatrughana Prasad Agrawal 14409 F/N/00029 Deoria 0 18 Binod Kumar Gupta 28395 F/E/00030 Chaibasa 0 19 A H Dave 34868 F/W/00033 Narayanpur 0 20 J.C.Gupta (M/S.J.C.Gupta & Co.Pvt Ltd) 8616 F/N/00036 New Delhi 0 21 Rakesh Trivedi 16997 F/W/00038 Shadolal -2000 22 K P Senthil Kumar 68308 A/S/00041 Chennai 0 23 Mohan S 26591 F/S/00042 Namakkal 0 24 V Ratnavel 6362 F/S/00046 COIMBATORE -2000 25 R Raja Rathina Kumar 16998 F/S/00047 CHENNAI 0 26 K Selvaraj 21309 F/S/00048 Erode 0 27 M Nirmal Kumar 28848 F/S/00049 Erode 0 28 M Gopalakrishnan 41996 A/S/00050 Erode 0 29 P Ravikumar 6087 F/S/00051 Erode 0 30 N Varadarajan 56968 A/W/00054 Nagaur 0 31 K Kothandaraman 54605 A/S/00057 Chennai 0 32 Sanjeev Soni 15006 F/N/00059 New Delhi 0 33 G P Penchala Reddy