Competitor Analysis5 a Horse Never Runs So Fast As When He Has Other Horses to Catch up and Outpace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marc Brennan Thesis

Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia Marc Brennan, BA (Hons) Creative Industries Research and Applications Centre (CIRAC) Thesis Submitted for the Completion of Doctor of Philosophy (Creative Industries), 2005 Writing to Reach You Keywords Journalism, Performance, Readerships, Music, Consumers, Frameworks, Publishing, Dialogue, Genre, Branding Consumption, Production, Internet, Customisation, Personalisation, Fragmentation Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia The music press and music journalism are rarely subjected to substantial academic investigation. Analysis of journalism often focuses on the production of news across various platforms to understand the nature of politics and public debate in the contemporary era. But it is not possible, nor is it necessary, to analyse all emerging forms of journalism in the same way for they usually serve quite different purposes. Music journalism, for example, offers consumer guidance based on the creation and maintenance of a relationship between reader and writer. By focusing on the changing aspects of this relationship, an analysis of music journalism gives us an understanding of the changing nature of media production, media texts and media readerships. Music journalism is dialogue. It is a dialogue produced within particular critical frameworks that speak to different readers of the music press in different ways. These frameworks are continually evolving and reflect the broader social trajectory in which music journalism operates. Importantly, the evolving nature of music journalism reveals much about the changing consumption of popular music. Different types of consumers respond to different types of guidance that employ a variety of critical approaches. -

Felix Baumgartner & Red Bull Media

Issue No. 14 MediaTainmentFINANCEd Appreciate the Value to Business MIPCube fever is back For Decision-Makers and StrategistsmentMT; @JayKayMed Creativity Brings The second edition of the Who Value Creativity an Expendables producer in WWII drama future-of-TV event heats up www.mediatainmentfinance.com Head to Cannes Facebook: MediaTainment Finance; during MIPTV 8-11 April 2013 Twitter: @Mediatain or Tune into www.mipcube.com nvestors spin new Carmaggedon … 3-14 quin romances e-books NEWS Toast & Jam goes sweet on film ; film: Print mediaNitin Sawhneytune into TV;in direct-to-disc Goldman Sachs history sells 50% of CSI page 15 tv: UK tax relief delayed; I Qatar fund 3D printer escalates revolutionises stake in Tiffany’s home building music: Time Warner; Harle games: Stephen King’s novel digital campaign stuck right in the middle of fashion: dia collaborations architecture: India backs theme-park tourism books/prints:Europe’s Illegal richest to retransmit soccerPhotographer players live broadcastin censorship lawsuit country has spawned some of the world’s ads/marketing: sport: page 26 page 34 copyright: investors are lining up for Sports, a share brand … and me Europe’s biggest economy is live entertainment: r jumped from the edge of space and became photography/art: have denounced it as “the FEATURES & REPORTS Don’t turn your nose GERMANY: just text and be key to the never-ending fiscal euro crisis; but this of America’s most respected TV channels; biggest media empires, and foreign s its country of origin, Qatar, fit in? … MIPCube Feature: FELIX The USBAUMGARTNER Administration is said to &page 39 RED BULL MEDIA HOUSE flew to new heights when skydiver Baumgartne the first human to break the speed of sound in free fall; ngfind devices out how might Red hold Bull more and Red than Bull Media House used new technology to give him wings - literally .. -

Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

CHAPTER 9 Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning 9.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES When you have read this chapter you should be able to understand: (a) the nature and purpose of market segmentation; (b) the contribution of segmentation to effective marketing planning; (c) how markets can be segmented, and the criteria that need to be applied if segmentation is to prove cost-effective; (d) how product positioning follows from the segmentation process; (e) the bases by which products and brands can be positioned effectively. 9.2 INTRODUCTION In Chapters 5 –7 we focused on approaches to environmental, customer and competitor analysis, and the frameworks within which strategic mar- keting planning can best take place. Against this background we now turn to the question of market segmentation, and to the ways in which compa- nies need to position themselves in order to maximize their competitive advantage and serve their target markets in the most effective manner. It does need to be recognized, however, that for many organizations the stra- tegic issues of market segmentation, market targeting and positioning often take on only a minimal role. A variety of authors (see, for example, Saunders, 1987; Solomon et al., 2006) have all pointed to the way in which approaches to segmentation are often poorly thought out and then poorly implemented. Strategic Marketing Planning Copyright © 2009 Colin Gilligan and Richard M.S. Wilson. All rights reserved. 339 340 CHAPTER 9: Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning There are several possible reasons for views such as these, although, in the case of companies with a broadly reactive culture, it is often due largely to a degree of organizational inertia, which leads to the fi rm being content to stay in the same sector of the market for some considerable time. -

Competitive Analysis for a Growth Mindset

Competitive Analysis for a Growth Mindset Competitive Analysis for a Growth Mindset 1 Building a Growth Marketing Plan with Competitive Analysis: What Every Marketer Needs to Know Building and scaling marketing is hard work—from creating content to launching campaigns to analyzing and optimizing channels, there’s work to be done in every corner. While you’re trying to attract and engage your personas, it turns out, so are your competitors. Your competitors’ content, campaigns, and solutions are affecting how those target customers perceive you, and affect the impact of all of your marketing efforts. So how do you fuel your growth in light of all of the market changes around you? The key is understanding and analyzing your competitors’ moves and incorporating those lessons into your growth marketing plans. In this guide, we’ll dive into the how-to of completing a full competitive analysis, outline a methodology for incorporating competitive analysis into each area of your marketing plan, and dig into the details of turning competitive insights into marketing wins across product marketing, demand gen, content marketing, and branding and PR. Businesses report having an average of 25 competitors in their market, and 87% say that their market has become more competitive in the last three years. Crayon State of Competitive Intelligence 2019 Competitive Analysis for a Growth Mindset 2 What is Competitive Analysis? Competitive analysis is the process of studying your market landscape and each player in that market to uncover patterns and trends. In a business context, this means digging deep into the solutions, marketing, teams, and more of each of your rivals to understand their strengths, weaknesses, and strategies in order to determine your own plan of action to grow and win. -

Michael E. Porter

COMPETITIVE Books by Michael E. Porter The Competitive Advantage of Nations ( 1990) Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Pe$ormance (1985) Cases in Competitive Strategy (1982) Competition in the Open Economy (with R.E. Caves and A.M. Spence) (1 980) Interbrand Choice, Strategy and Bilateral Market Power (1976) COMPETITIVE STRATEGY Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors With a new Introduction Michael E. Porter THE FREE PRESS THE FREE PRESS A Division of Simon & Schuster Inc 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Copyright O 1980 by The Free Press New introduction copyright O 1998 by The Free Press All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. First Free Press Edition 1980 THE FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America 62 61 60 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, Michael E. Competitive strategy: techniques for analyzing industries and competitors: with a new introduction1 Michael E. Porter. p. cm. .. Originallypublished: New York: Free Press, c I980 Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Competition. 2. Industrial management. I. Title. HD4 1 .P67 1998 658dc21 98-9580 CIP ISBN 0-684-84148-7 Contents Introduction Preface xvii Introduction, 1980 xxi PART I General Analytical Techniques CHAPTER 1 THE STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF INDUSTRIES 3 Structural Determinants of the Intensity of Competition 5 Structural Analysis and Competitive Strategy 29 Structural Analysis -

For Everyone in the Business of Music

FOR EVERYONE IN THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC #5f>%J - .>V# f - 103S APPEARANCESOF COMPETITIONS DURING ACROSS OCTOBER ALL NETWORKS 1NCLUDING PLUS A PERFORMANCE ALL SAINTS WILL ON JO B INC THF 4?miuî?DriTcRVIEWS SCHEDULED TO AIR ON CAPITAL AND ILR NATIONAL OUTDOOR POSTER CAMPAIGN NATIONAL TV ADS MIDUNDS CHANNEL 4 & WNN^WEEK^MMFNr'MG 16TH CHANNEL 4 THROUGHOUT NOVEMBER ANn n^E TI0NALEMBER CHANNEL E PHASETHE THIRD OF THE SINGLE ALBUM 'ALL CAMPAIGN) HOOKED UP' in ,ÏSn.ANUARYil 20001 "-EAOING TH1S WILL TO U NATIONAL PRESS ADS ADS DWILL MAPPEARC INLUDING THE POPthe pdcccdaey .. ^ 5 ri ™ndMUCH more . ' So^sTHEATO S0 I■ NEWS:accelerating The theBl digital \ NEWS: A TV deal wilh NEWS: Sine is || âge under JENNY j Channelal Q 4AWARDS is giving itsthe | clubtargeting scene the in grassrootthe lead- | ■ launchVISKY.withthe of five channels |- Ij| event'shighest 11profile -year in history the up to FATBOV SLIM's I Marketing dotmusic breaks the 1m tyç barrierfor monthlyusers^ ri e a pand Music Week slster li m dotmusicmusic website has outsidebecome ofthe theTis Prst tomonthlyonthly offlciaTiy"break usetuse[ mark. thrôûitmreTïn electronlc,The figure, was auditedrecorded by across ABC July.1,254,679 dotmusic unique usersregistered and long-runningBrits TV will Brits initially organiser be staffed lisa by the16,762,198 period. pageUset impressionsnumbers have for ofAnderson, executive who producer, takes on theand positionformer DecemberIncreased by1999 70% figureslnce theof lunching Brits TV 740,964, and five-fold slnce May Awards brand could be tied to, the opportunitiescreated that in récognitionnew technolo- of lntr duci show'sIts launch links with effectively Initial TV, severs which hasthe thishave ail a yeardedicated round." i jazz-relatedalthough it isshows thought are that Wio dance- options and gyevolvingthe and new média brand," présent he says. -

The Importance and Level of Adaptation of STP Strategies for Growth in Foreign Markets: in the Case of Soft Drinks Company

Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting 19(2): 13-23, 2020; Article no.AJEBA.61566 ISSN: 2456-639X The Importance and Level of Adaptation of STP Strategies for Growth in Foreign Markets: In the Case of Soft Drinks Company Md. Mahathy Hasan Jewel1 and Kh Khaled Kalam2* 1Department of Marketing, Jagannath University, Bangladesh. 2Economics and Business School, Shandong Xiehe University, China. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJEBA/2020/v19i230299 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Fang Xiang, University of International and Business Economics, China. (2) Dr. Chan Sok Gee, University of Malaya, Malaysia. Reviewers: (1) Getie Andualem Imiru, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. (2) Najah Hassan Salamah, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. (3) Huseyin Altay, Inonu University, Turkey. (4) Ibajanaishisha M. Kharbudon, Fazl Ali College, India. (5) M. Beulah Viji Christiana, Anna University, India. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/61566 Received 10 August 2020 Accepted 15 October 2020 Case Study Published 12 November 2020 ABSTRACT STP denotes Segmentation, Targeting, and Positioning. This study's main purpose is to demonstrate the STP concept's understanding and its importance in the success or failure of a Soft Drinks company. Examines the competitive role of Soft Drinks in the global soft beverage industry. Since they operate in over 200 countries, they have a simple choice as to whether their products are standardized worldwide and whether they can benefit from economies of magnitude and adapt their products to a given market. -

Strategic Analysis Tools

Topic Gateway Series Strategic Analysis Tools Strategic Analysis Tools Topic Gateway Series No. 34 1 Prepared by Jim Downey and Technical Information Service October 2007 Topic Gateway Series Strategic Analysis Tools About Topic Gateways Topic Gateways are intended as a refresher or introduction to topics of interest to CIMA members. They include a basic definition, a brief overview and a fuller explanation of practical application. Finally they signpost some further resources for detailed understanding and research. Topic Gateways are available electronically to CIMA Members only in the CPD Centre on the CIMA website, along with a number of electronic resources. About the Technical Information Service CIMA supports its members and students with its Technical Information Service (TIS) for their work and CPD needs. Our information specialists and accounting specialists work closely together to identify or create authoritative resources to help members resolve their work related information needs. Additionally, our accounting specialists can help CIMA members and students with the interpretation of guidance on financial reporting, financial management and performance management, as defined in the CIMA Official Terminology 2005 edition. CIMA members and students should sign into My CIMA to access these services and resources. The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants 26 Chapter Street London SW1P 4NP United Kingdom T. +44 (0)20 7663 5441 F. +44 (0)20 7663 5442 E. [email protected] www.cimaglobal.com 2 Topic Gateway Series Strategic -

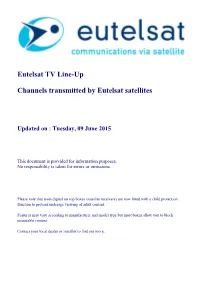

Linup Report

Eutelsat TV Line-Up Channels transmitted by Eutelsat satellites Updated on : Tuesday, 09 June 2015 This document is provided for information purposes. No responsibility is taken for errors or omissions. Please note that most digital set top boxes (satellite receivers) are now fitted with a child protection function to prevent underage viewing of adult content. Features may vary according to manufacturer and model type but most boxes allow you to block unsuitable content. Contact your local dealer or installer to find out more. Freq Beam Analo Diff Fec Symb Acces Lang g ol Rate EUTELSAT 117 WEST A 3.720 V C Edusat package DVB-S 3/4 27.000 C Telesecundaria TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV Docencia TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 13 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C UnAD TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 15 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Canal 22 Nacional TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Telebachillerato TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 18 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Tele México TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV Universidad TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Red de las Artes TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Aprende TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Canal del Congreso TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Especiales TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Transmisiones Especiales 27 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV UNAM TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish 3.744 V C INE TV TV DVB-S2 3/4 2.665 Spanish 3.748 V C Radio Centro radio DVB-S 7/8 2.100 Spanish 3.768 V C Inti Network TV DVB-S2 3/4 4.800 Spanish 3.772 V C Gama TV TV DVB-S 3/4 3.515 BISS Spanish 3.786 V -

Competitor Analysis Topic Gateway Series No.21

Topic Gateway Series Competitor Analysis Competitor Analysis Topic Gateway Series No.21 1 Prepared by Ray Perry, Michelle Ross and Technical Information Service Revised November 2008 Topic Gateway Series Competitor Analysis About Topic Gateways Topic Gateways are intended as a refresher or introduction to topics of interest to CIMA members. They include a basic definition, a brief overview and a fuller explanation of practical application. Finally they signpost some further resources for detailed understanding and research. Topic Gateways are available electronically to CIMA members only in the CPD Centre on the CIMA website, along with a number of electronic resources. About the Technical Information Service CIMA supports its members and students with its Technical Information Service (TIS) for their work and CPD needs. Our information and accounting specialists work closely together to identify or create authoritative resources to help members resolve their work related information needs. Additionally, our accounting specialists can help CIMA members and students with the interpretation of guidance on financial reporting, financial management and performance management, as defined in the CIMA Official Terminology 2005 edition. CIMA members and students should sign into My CIMA to access these services and resources. The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants 26 Chapter Street London SW1P 4NP United Kingdom T. +44 (0)20 7663 5441 F. +44 (0)20 7663 5442 E. [email protected] www.cimaglobal.com 2 Topic Gateway Series Competitor Analysis Competitor Analysis Definition Competitor analysis is defined as the: ‘Identification and quantification of the relative strengths and weaknesses (compared with competitors or potential competitors), which could be of significance in the development of a successful competitive strategy.’ CIMA Official Terminology Guide 2005 Competitor analysis involves understanding and analysing businesses which compete directly or indirectly with your business in at least one market, product category or service. -

Marketing Module 4: Competitor Analysis

June 2013 EB 2013-05 MARKETING MODULES SERIES Marketing Module 4: Competitor Analysis Sandra Cuellar-Healey, MFS MA Miguel Gomez, PhD Charles S. Dyson School of Applied Economics & Management College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Cornell University, Ithaca NY 14853-7801 Table of Contents Page Foreword……………………………………………………………………………………...4 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………....5 2. Competitor Analysis Defined…………………………………………………………...5 3. Identifying Current and Potential Competitors……………………………………….5 3.1 Industry-Based Analysis……………………………………………………………...6 3.2 Market-based Analysis……………………………………………………………….7 4. Competitor Profiling…………………………………………………………………….8 5. Assessing Market Attractiveness……………………………………………………….10 6. Designing Competitive Strategies ……………………………………………………..12 6.1 Market Leader………………………………………………………………………..12 6.1.1 Expanding total market………………………………………………………12 6.1.2 Defending market share……………………………………………………...13 6.1.3 Expanding market share……………………………………………………...13 6.2 Market Challenger…………………………………………………………………...13 6.3 Market Follower……………………………………………………………………...14 6.4 Market Nicher………………………………………………………………………..15 References…………………………………………………………………………………...16 Supplement No. 1 – Example of a SWOT Analysis for Whole Foods………………………..17 Supplement No. 2 - Example of a SWOT Analysis for Mc Donald’s………………………...18 Foreword A marketing strategy is something that every single food and agriculture-related business (farms, wholesalers, retailers, etc.), no matter how big or small, needs to have in place in order to succeed in the marketplace. Many business owners in the food and agriculture sector in New York State and elsewhere are hesitant to set up an actual marketing strategy because they simply do not know how to go about developing it. How to better market their products and services remains a primary concern among New York State food businesses as a result. In response to this need, we offer this Marketing Modules Series of eight modules which constitute a comprehensive training course in marketing management. -

Competitor Analysis and Accounting (Relevant to Paper II -- PBE Management Accounting and Finance) Dr Fong Chun Cheong, Steve S

Competitor analysis and accounting (Relevant to Paper II -- PBE Management Accounting and Finance) Dr Fong Chun Cheong, Steve School of Business, Macao Polytechnic Institute Every day we see competition in products and services in a modern business society. Competitor analysis and accounting is a central issue in strategic management accounting. These techniques help companies analyze and master the competitive situation. Competitor analysis and accounting is also called competitor-focused accounting or accounting for the competition. Key benefits of competitor analysis and accounting Competitor analysis and accounting is regarded as a central element in business planning and control. There are four key benefits of competitor analysis and accounting: 1. Industry benchmarking. Companies compare themselves with similar companies in the same industry to identify their strengths and weaknesses. For example, Bank of East Asia sets Hang Seng Bank as its benchmark for comparison, as both are local banks in Hong Kong. 2. Learning from competitors. Companies study their similar market experiments to those which they are planning. For example, mobile phone service companies compare plans of other mobile companies when planning a new promotion of phone services. 3. Positioning. Companies try to identify their competitors’ strengths when choosing competition methods, either by cutting the product price to exercise cost leadership or by launching a new product or service to achieve product specialization. 4. Identifying opportunities and threats. Competitor analysis and accounting links with the traditional strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis for handling both business opportunities and threats. Some query why competitor analysis is critical for identifying opportunities and threats. To answer this, think about what questions an organization should ask to identify these.