©2010 Nicole Bryan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simić Miroslav Tadić Simo Zarić

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No. IT-95-9-T Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 17 October 2003 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN TRIAL CHAMBER II Before: Judge Florence Ndepele Mwachande Mumba, Presiding Judge Sharon A. Williams Judge Per-Johan Lindholm Registrar: Mr. Hans Holthuis Judgement: 17 October 2003 PROSECUTOR v. BLAGOJE SIMIĆ MIROSLAV TADIĆ SIMO ZARIĆ JUDGEMENT The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Gramsci Di Fazio Mr. Philip Weiner Mr. David Re Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Igor Panteli} and Mr. Srdjan Vuković for Blagoje Simi} Mr. Novak Lukić and Mr. Dragan Krgović for Miroslav Tadić Mr. Borislav Pisarević and Mr. Aleksandar Lazarevi} for Simo Zarić PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/aa9b81/ I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................1 II. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING THE EVALUATION OF EVIDENCE ...........7 III. DEMOGRAPHICS EXPERTS REPORTS .................................................................................11 IV. RELEVANT LAW ON ARTICLE 5 OF THE STATUTE.........................................................13 A. LAW ON GENERAL REQUIREMENTS OF ARTICLE 5 ......................................................................13 B. LAW ON PERSECUTION................................................................................................................16 1. General requirements: chapeau -

Memorial of the Republic of Croatia

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING THE APPLICATION OF THE CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE CRIME OF GENOCIDE (CROATIA v. YUGOSLAVIA) MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA APPENDICES VOLUME 5 1 MARCH 2001 II III Contents Page Appendix 1 Chronology of Events, 1980-2000 1 Appendix 2 Video Tape Transcript 37 Appendix 3 Hate Speech: The Stimulation of Serbian Discontent and Eventual Incitement to Commit Genocide 45 Appendix 4 Testimonies of the Actors (Books and Memoirs) 73 4.1 Veljko Kadijević: “As I see the disintegration – An Army without a State” 4.2 Stipe Mesić: “How Yugoslavia was Brought Down” 4.3 Borisav Jović: “Last Days of the SFRY (Excerpts from a Diary)” Appendix 5a Serb Paramilitary Groups Active in Croatia (1991-95) 119 5b The “21st Volunteer Commando Task Force” of the “RSK Army” 129 Appendix 6 Prison Camps 141 Appendix 7 Damage to Cultural Monuments on Croatian Territory 163 Appendix 8 Personal Continuity, 1991-2001 363 IV APPENDIX 1 CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS1 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE CHRONOLOGY BH Bosnia and Herzegovina CSCE Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe CK SKJ Centralni komitet Saveza komunista Jugoslavije (Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia) EC European Community EU European Union FRY Federal Republic of Yugoslavia HDZ Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (Croatian Democratic Union) HV Hrvatska vojska (Croatian Army) IMF International Monetary Fund JNA Jugoslavenska narodna armija (Yugoslav People’s Army) NAM Non-Aligned Movement NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organisation -

Peace Youth Group Danube , Vukovar

3. Struggling for the Right to a Future: Peace Youth Group Danube , Vukovar The Post-war Landscape of Vukovar In 1991, Vukovar was under siege for full three months, completely destroyed and conquered by the Yugoslav Army and the Serbian paramilitary forces on November 18, 2001, which was accompanied by a massacre of civilian population, prisoners of war and even hospital patients. More than 22 000 non-Serb inhabitants were displaced and around 8000 ended up in prisons and concentration camps throughout Serbia. The town remained under the rule of local Serb self- proclaimed authorities until the signing of the Erdut Agreement in November 1995, followed by the establishment of UN Transitional Administration in the region of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium (UNTAES) and the region’s full reintegration into the Republic of Croatia on January 15, 1998. During the two years of UNTAES, deemed one of the most successful UN missions ever of its kind, demilitarization, local elections (1997) and peaceful reintegration into the Republic of Croatia were achieved without major incidents, resulting in a considerably higher percentage of remaining Serbs, in comparison to other parts of Croatia that were reintegrated by means of military operations. At the same time, the processes of confidence building, resolution of property issues and investments into social and economic revitalization have been much slower than needed, considering the severity of devastation and trauma inflicted by the war. Despite the fact that the town of Vukovar represents the most prominent symbol of war suffering and destruction in Croatia the quality of life of its post-war inhabitants, a half of whom are returnees, has remained the worst in Croatia, with unemployment rate of 37%, incomplete reconstruction of infrastructure, only recently started investments into economic recovery, lack of social life and education opportunities and severe division along ethnic lines marking every sphere of political and daily life in Vukovar. -

Global Information Society Watch 2009 Report

GLOBAL INFORMATION SOCIETY WATCH (GISWatch) 2009 is the third in a series of yearly reports critically covering the state of the information society 2009 2009 GLOBAL INFORMATION from the perspectives of civil society organisations across the world. GISWatch has three interrelated goals: SOCIETY WATCH 2009 • Surveying the state of the field of information and communications Y WATCH technology (ICT) policy at the local and global levels Y WATCH Focus on access to online information and knowledge ET ET – advancing human rights and democracy I • Encouraging critical debate I • Strengthening networking and advocacy for a just, inclusive information SOC society. SOC ON ON I I Each year the report focuses on a particular theme. GISWatch 2009 focuses on access to online information and knowledge – advancing human rights and democracy. It includes several thematic reports dealing with key issues in the field, as well as an institutional overview and a reflection on indicators that track access to information and knowledge. There is also an innovative section on visual mapping of global rights and political crises. In addition, 48 country reports analyse the status of access to online information and knowledge in countries as diverse as the Democratic Republic of Congo, GLOBAL INFORMAT Mexico, Switzerland and Kazakhstan, while six regional overviews offer a bird’s GLOBAL INFORMAT eye perspective on regional trends. GISWatch is a joint initiative of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and the Humanist Institute for Cooperation with -

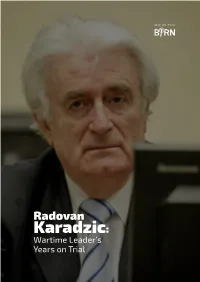

PUBLLISHED by Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’S Years on Trial

PUBLLISHED BY Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’s Years on Trial A collection of all the articles published by BIRN about Radovan Karadzic’s trial before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the UN’s International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. This e-book contains news stories, analysis pieces, interviews and other articles on the trial of the former Bosnian Serb leader for crimes including genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Produced by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Introduction Radovan Karadzic was the president of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Repub- lika Srpska during wartime, when some of the most horrific crimes were committed on European soil since World War II. On March 20, 2019, the 73-year-old Karadzic faces his final verdict after being initially convicted in the court’s first-instance judgment in March 2016, and then appealing. The first-instance verdict found him guilty of the Srebrenica genocide, the persecution and extermination of Croats and Bosniaks from 20 municipal- ities across Bosnia and Herzegovina, and being a part of a joint criminal enterprise to terrorise the civilian population of Sarajevo during the siege of the city. He was also found guilty of taking UN peacekeepers hostage. Karadzic was initially indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in 1995. He then spent 12 years on the run, and was finally arrested in Belgrade in 2008 and extradited to the UN tribunal. As the former president of the Republika Srpska and the supreme com- mander of the Bosnian Serb Army, he was one of the highest political fig- ures indicted by the Hague court. -

19 August 2008 in the NAME OF

SUD BOSNE I HERCEGOVINE СУД БОСНЕ И ХЕРЦЕГОВИНЕ Number: X-KRŽ-05/42 Sarajevo: 19 August 2008 IN THE NAME OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Section I for War Crimes, in the Panel of the Appellate Division composed of Judge Azra Miletić, as the President of the Panel, and Judges Doctor Miloš Babić and Robert Carolan, as the Panel members, with the participation of the Legal Officer Neira Kožo as the Record-taker, in the criminal case against the accused Nikola Andrun for the criminal offence of War Crimes against Civilians, in violation of Article 173(1)c) of the Criminal Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina (hereinafter: the CC BiH), in conjunction with Article 29 of the CC BiH, deciding on the Indictment of the Prosecutor’s Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina number: KT-RZ-28/05 dated 12 August 2008, following the trial in the presence of the Prosecutor of the Prosecutor’s Office of BiH, Vesna Budimir, the accused Nikola Andrun and his Defense Counsel, lawyer Hamdo Kulenović, rendered and on 19 August 2008 publically announced the following: VERDICT THE ACCUSED NIKOLA ANDRUN, son of Drago and mother Zora nee Nikolić, born on 22 November 1957 in the place of Domanovići, Municipality Čapljina, JMBG 2211957151130, permanent place of residence in Čapljina at St. Fra Didaka Buntića bb, of Croatian ethnicity, merchant by occupation, unemployed, married, a father of four, citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic of Croatia, prior conviction by the Verdict of the Basic Court in Stolac number: Kž-2/94 of 15 March 1994 to imprisonment for a term of 5 (five) months, 2 (two) years on probation and a ban on driving „B“ category motor vehicles for a period of 8 (eight) months for the criminal offence in violation of Article 185(1) and Article 181(1) of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, detained in the Correctional Establishment “Kula” since 30 November 2005, IS GUILTY Kraljice Jelene br. -

An Analysis of the European Union's Conflict Resolution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sabanci University Research Database AN ANALYSIS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION’S CONFLICT RESOLUTION INTERVENTION IN POST-CONFLICT CROATIA AND THE FORMER YUGOSLAV REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA By ATHINA GIANNAKI Submitted Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabanci University June 2007 ii AN ANALYSIS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION’S CONFLICT RESOLUTION INTERVENTION IN POST-CONFLICT CROATIA AND THE FORMER YUGOSLAV REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA By ATHINA GIANNAKI Submitted Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabanci University June 2007 iii To my family and Andreas iv © Athina G. Giannaki 2007 All Rights Reserved v ABSTRACT AN ANALYSIS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION’S CONFLICT RESOLUTION INTERVENTION IN POST-CONFLICT CROATIA AND THE FORMER YUGOSLAV REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Athina Giannaki M.A. in Conflict Analysis and Resolution Supervisor: Dr. Nimet Beriker Croatia and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) are two countries which have been established after the disintegration of Yugoslavia, in 1991. Shortly after its independence and till 1995 Croatia faced a bloody civil war, between the government and the Serbian minority of the country. FYROM avoided a full scaled war, but it faced a destructive crisis in 2001 between the government and the Albanian minority. The crisis, however, was managed quickly, especially with the help of the international community. This thesis examines the type of European Union’s (EU) intervention, as a third party, in the post-conflict environment of the two countries. -

The Left in the Post-Yugoslav Area There Is Probably No Other Region in Europe Where the Past and Present of the Left Are So

Boris Kanzleiter/Đorde Tomi ´c the leFt in the Post-yugoslav area There is probably no other region in Europe where the past and present of the left are so severely out of sync with one another as they are in former Yugoslavia. A look at the history of the area reveals a strong presence of the socialist and communist movement. Prior to the First World War, such socialists as Svetozar Marković were able to lay the foundations of a revolutionary movement. At the beginning of the 1920s, the newly founded Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) was able to achieve the breakthrough of becoming a mass party. After the German invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, the anti-fascist partisans were able not only to mobilize hundreds of thousands of fight- ers, but also, then, to overthrow the monarchy and establish a new socialist state. The break with Moscow in 1948 initiated the experiment of «workers’ self-management» and «the non-aligned movement», which attracted worldwide attention. State and party leader Josip Broz Tito and the ruling League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ) enjoyed enormous worldwide prestige during the 1960s and ’70s. Moreover, such left oriented opposition tendencies critical of Tito such as the Praxis Group, which called for a «humanistic Marxism», were noted worldwide. This rich history contrasts sharply with the situation of the left at present. At the beginning of the 21st century, the left in former Yugoslavia underwent an existential crisis. The point of departure for the decline was the severe structural, social and political crisis of the late phase of socialism in the 1980s. -

Conscientious Objectors in Croatia in the 1990S

WHO OWNS YOUR BODY: CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS IN CROATIA IN THE 1990S Oliwia Berdak * UDK: 355.212.7(497.5)”1990” 355.245(497.5)”1990” 172.1:355.2(497.5)”1990” Izvorni znanstveni rad Primljeno: 12.II.2013. Prihvaćeno: 26.II.2013. Summary The collapse of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s changed little in the relationship between male citizens and the state. In fact, ownership of men’s bodies became a token of statehood, as different republics assumed and legislated their right to draft men into their smaller armies. In Croatia, men could, at least nominally, exercise their new right to conscientious objection from 1990 onwards. This article traces the adoption and implementation of the Article 47 of the Croatian Constitution in 1990, which allowed conscientious objec- tors to complete civilian instead of military service. I draw upon letters to the Croatian Ministry of Defence, written in the 1990s by men who claimed their right to conscien- tious objection, to investigate the constraints and possibilities of voicing dissent by men at this time. How men narrated their reasons and motivations portrays the dilemmas of pacifism in the context of a defensive war. Even in these narrow frames, men have found enough space to evoke their own understandings of democratisation, individual rights and European political standards, narratives which were later used in calls to abandon military conscription altogether. Key words: Conscientious objection, conscription, military, citizenship, Croatia, masculinities This topic brings me to that worst outcrop of the herd nature, the military system, which I abhor. That a man can take pleasure in marching in formation to the strains of a band is enough to make me despise him. -

Time for Truth

TIME FOR TRUTH Review of the Work of the War Crimes Chamber of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2005-2010 Sarajevo, 2010. Publisher Balkanske istraživačke mreže (BIRN) BIH www.bim.ba Written by Aida Alić Editors Aida Alić and Anna McTaggart Proof Readers Nadira Korić and Anna McTaggart Translated by Nedžad Sladić Design Branko Vekić DTP Lorko Kalaš Print 500 Photography All photographs in this publication are provided by the Archive of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This guidebook is part of BIRN’s Transitional Justice Project. Its production was finan ced by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This publication is available on the website: www.bim.ba ------------------------------------------------- CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo 341.322.5:343.1]:355.012(497.6)”1992/1995” ALIĆ, Aida Time for truth : review of the work of the war crimes Chamber of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2005-2010 / [written by Aida Alić] ; [translated by Nedžad Sladić ; photography Archive of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina]. - Sarajevo : Balkanske istraživačke mreže BiH, BIRN, 2010. - 231 str. : ilustr. ; 25 cm ISBN 978-9958-9005-5-6 COBISS.BH-ID 18078214 ------------------------------------------------- SADRŽAJ 7 Introduction 9 Abbreviations 10 Glossary 12 From the Law 19 Plea Agreements 21 Bjelić Veiz (Vlasenica) 23 Četić Ljubiša (Korićanske stijene) 25 Đurić Gordan (Korićanske stijene) 27 Fuštar Dušan (logor “Keraterm”, Prijedor) 29 Ivanković Damir -

Pdacl155.Pdf

ccover.aiover.ai 77/18/07/18/07 22:38:52:38:52 PPMM “Our thanks to AED and USAID for the enthusiasm invested in the development of civil society in Croatia!” “Through work and cooperation with USAID/AED, I have personally established numerous contacts with NGOs all over Croatia and gained a lot of new knowledge and experiences C that I will certainly use to make my work in the future more successful and comprehen- sive. Thank you!” M Y “Everything was great! I'm sorry you're leaving. You have left an important mark on the development and structure of non-governmental organizations in Croatia.” CM MY “A flexible approach to the financial and professional support to NGOs; recognition of needs “as we go”, clear, unambiguous communication based on respect. Congratula- CY tions!” CMY “Who will organize conferences after AED leaves? Thank you for the support and K knowledge you have provided over the past years. Conferences and workshops were a great place for CSOs to socialize, exchange experiences, establish new contacts and cooperation. I wish luck to all AED staff in their future work, and hope that we will continue cooperating - personally or professionally. Thank you!” “Through its varied and well-adjusted grant programs, the CroNGO Program introduced new topics important for the development of civil society in Croatia, increased the capaci- ties of a large number of NGO activists and gave the chance even to small organizations. All in all, I think that the support provided by this program was among the most compre- hensive kinds of support to the development of civil society in Croatia. -

New Networks 1 If You Mention the Term New Media in The

New Media – New Networks 1 If you mention the term new media in the presence of one of the most prominent artists in the extremely popular virtual world Second Life Gazira Barbelli, you will automatically activate a programme script, which will literally blow your avatar away to a completely different, unwanted location. The script entitled Don't Say Tornado is the artwork Barbelli created to draw attention to an inappropriate use of new media theory, not only in the context of a completely artificial world such as Second Life, but in a contemporary culture as well. Although the Croatian new media art is far from being thoroughly virtual, the example of Second Life indicates the current process of redefining the new media culture in relation to the increase in the number of the Internet users, changes in the ways it is used, faster introduction of new media theory into traditional scientific fields etc. In a somewhat modified version of his early new media theory (The Language of New Media), Lev Manovich raises a question whether there is any sense in talking about new media in the culture that has already adopted digital production, processing and distribution of information. Therefore, he has developed eight theses for distinguishing new media from the old ones, claiming that the list itself is a work in progress 2. On the other hand, Geert Lovink points out that new media are at a critical juncture. According to him, new media are facing the mass adoption of new technologies, fast Internetisation of a non-Western world, the increase in capacity of the Internet and its new uses known as Web 2.0.