ANTON MAUVE (Zaandam 1838 - Arnhem 1888)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generaal Urquhartlaan 4 6861 GG Oosterbeek

Generaal Urquhartlaan 4 6861 GG Oosterbeek Postbus 9100 6860 HA Oosterbeek Telefoon (026) 33 48 111 Fax (026) 33 48 310 Aan de leden van de gemeenteraad van Renkum Internet www.renkum.nl IBAN NL02BNGH0285007076 KvK 09215649 Datum Onderwerp 2 maart 2021 Inventarisatie ontmoeting Beste leden van de raad, voorzitter, Aanleiding Tijdens de commissievergadering van 9 februari is door Gemeentebelangen gevraagd naar de uitkomsten van de inventarisatie wat de verbindingen zijn in de verschillende dorpen om zo de cohesie te verbeteren. Beleidsvisie In de Kadernota Sociaal Domein 2019 is opgenomen dat wij inzetten op meer nabij, preventief, dorpsgericht en integraal. Daarbij is het belangrijk dat we per dorp/kern een stevig netwerk creëren met onze partners, voldoende algemene voorzieningen organiseren voor dat wat binnen de dorpen speelt en een model ontwikkelen waarmee we ingezette zorg/hulp eenvoudig en snel op en af kunnen schalen. Deze werkwijze is de rode draad van de ondersteuning die wij onze inwoners willen geven die zij nodig hebben, tegen de kosten die we kunnen financieren. De sociale basis bestaat uit wat inwoners zelf kunnen en wat zij samen met en voor elkaar doen. Dit varieert van burenhulp tot allerlei vrijwilligersinitiatieven, zoals hulp bij het invullen van formulieren of kleine klussen in- en rondom het huis. Wanneer we spreken over de inwoner en zijn eigen netwerk, dan is dit in Renkum relatief kansrijk. Veel mensen in onze gemeente bereid zijn iets voor een ander te doen en dat schept kansen. Ook helpt een sterke sociale basis professionals om inwoners goed te verbinden aan netwerken, activiteiten en algemene voorzieningen in de buurt. -

Simonis & Buunk

2019 / 2020 Gekleurd Gekleurd Gekleurd grijs grijs SIMONIS & BUUNK SIMONIS & BUUNK EEN KEUR AAN KUNST cover Haagse School_2019_bs.indd 1 06-11-19 16:00 Gekleurd grijs Verkooptentoonstelling Haagse School zaterdag 30 november 2019 t/m zaterdag 4 januari 2020 Dinsdag t/m zaterdag van 11-17 uur en op afspraak open zondagen: 1, 15 en 29 december van 11-17 uur Een collectie schilderijen en aquarellen van de Haagse School. Voor prijzen en foto’s met lijst: simonisbuunk.nl SIMONIS & BUUNK EEN KEUR AAN KUNST 19e eeuw Notaris Fischerstraat 30 20e eeuw Notaris Fischerstraat 19 Fischerhuis Notaris Fischerstraat 27 Buiten exposities om geopend dinsdag t/m zaterdag 11-17 uur en op afspraak Notaris Fischerstraat 30, 6711 BD Ede +31 (0) 318 652888 [email protected] www.simonisbuunk.nl cover Haagse School_2019_bs.indd 2 06-11-19 16:00 Predicaat ‘meesterlijk’ Frank Buunk Als ik aan de Haagse School denk dan komt het jaar trouwe halfjaarlijkse bezoeken aan zijn goede vriend 1976 in mijn herinnering, toen ik voor het eerst over Scheen thuis kwam. de vloer kwam bij Rien Simonis als aanbidder van Kunsthandelaar Pieter Scheen, samensteller van de zijn oudste dochter Mariëtte. Al snel raakte ik ook ‘Rode Scheen’, was toen een begrip in kunstkringen. geboeid door de anekdotes uit de kunstwereld die In zijn kunsthandel aan de Zeestraat 50, recht mijn aanstaande schoonvader in geuren en kleuren tegenover het Panorama Mesdag, presenteerde hij kon vertellen. Pieter Scheen passeerde vaak de revue vanaf de jaren 50 schilderijen uit de Romantische in de sterke verhalen waarmee schoonvader na zijn School en de Haagse School. -

Vincent Van Gogh Le Fou De Peinture

VINCENT VAN GOGH Le fou de peinture Texte Pascal BONAFOUX lu par l’auteur et Julien ALLOUF translated by Marguerite STORM read by Stephanie MATARD LETTRES DE VAN GOGH lues par MICHAEL LONSDALE © Éditions Thélème, Paris, 2020 CONTENTS SOMMAIRE 6 6 Anton Mauve Anton Mauve The misunderstanding of a still life Le malentendu d’une nature morte Models, and a hope Des modèles et un espoir Portraits and appearance Portraits et apparition 22 22 A home Un chez soi Bedrooms Chambres The need to copy Nécessité de la copie The destiny of the doctors’ portraits Les destins de portraits de médecins Dialogue of painters Dialogue de peintres 56 56 Churches Églises Japanese prints Estampes japonaises Arles and money Arles et l’argent Nights Nuits 74 74 Sunflowers Tournesols Trees Arbres Roots Racines 94 ARTWORK INDEX 94 index des œuvres Anton Mauve 9 /34 Anton Mauve PAGE DE DROITE Nature morte avec chou et sabots 1881 Souvenir de Mauve 1888 Still Life with Cabbage and Clogs Reminiscence of Mauve 34 x 55 cm – Huile sur papier 73 x 60 cm – Huile sur toile Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Pays-Bas 6 7 Le malentendu d’une nature morte 10 /35 The misunderstanding of a still life Nature morte à la bible 1885 Still life with Bible 65,7 x 78,5 cm – Huile sur toile Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas 8 9 Souliers 1888 Shoes 45,7 x 55,2 cm – Huile sur toile The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA 10 11 Vue de la fenêtre de l’atelier de Vincent en hiver 1883 View from the window of Vincent’s studio in winter 20,7 x -

George Hendrik Breitner (1857-1923) Was Among the Most Successful Dutch Painters of the Nineteenth Century

George Hendrik Breitner (1857-1923) was among the most successful Dutch painters of the nineteenth century. Well known for his paintings of city scenes, a series of young women dressed in kimonos, cavalrymen and horses, Breitner also depicted cats in his sketches, paintings, and photo- graphs. Breitner was a cat lover: cats were always roaming around in his house and in his studio. This book contains a selection of his sketches and photographs of cats. George Hendrik Breitner Born in Rotterdam in 1857, George Hendrik Breitner began his studies at the Academy of Art, The Hague, in 1876. There he met painters of the Hague School who, influenced by the French Barbizon painters, preferred realism to romanticism. Soon known for his ability to paint horses, Breitner was hired by Hendrik Willem Mesdag in 1881 to paint the horses in his renowned panorama painting of Scheveningen, which can still be visited today in a specially built rotund gallery in The Hague. A year later Breitner befriended Vincent van Gogh, with whom he often went sketching in and around The Hague. Attracted by its vibrant artistic and cultural life spurred by a revival of economic growth, Breitner moved to Amsterdam in 1886. Here Breitner captured the city’s street life in many of his paintings. Horses remained an important subject for the artist, but he soon replaced his caval- ry horses with those pulling carts and trams. He often took his sketchbook on his walks through the town and, from around 1890, he would also take his Kodak camera out with him to capture scenes that would find their way into his paintings. -

Operation Market Garden WWII

Operation Market Garden WWII Operation Market Garden (17–25 September 1944) was an Allied military operation, fought in the Netherlands and Germany in the Second World War. It was the largest airborne operation up to that time. The operation plan's strategic context required the seizure of bridges across the Maas (Meuse River) and two arms of the Rhine (the Waal and the Lower Rhine) as well as several smaller canals and tributaries. Crossing the Lower Rhine would allow the Allies to outflank the Siegfried Line and encircle the Ruhr, Germany's industrial heartland. It made large-scale use of airborne forces, whose tactical objectives were to secure a series of bridges over the main rivers of the German- occupied Netherlands and allow a rapid advance by armored units into Northern Germany. Initially, the operation was marginally successful and several bridges between Eindhoven and Nijmegen were captured. However, Gen. Horrocks XXX Corps ground force's advance was delayed by the demolition of a bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal, as well as an extremely overstretched supply line, at Son, delaying the capture of the main road bridge over the Meuse until 20 September. At Arnhem, the British 1st Airborne Division encountered far stronger resistance than anticipated. In the ensuing battle, only a small force managed to hold one end of the Arnhem road bridge and after the ground forces failed to relieve them, they were overrun on 21 September. The rest of the division, trapped in a small pocket west of the bridge, had to be evacuated on 25 September. The Allies had failed to cross the Rhine in sufficient force and the river remained a barrier to their advance until the offensives at Remagen, Oppenheim, Rees and Wesel in March 1945. -

BARTHOLOMEUS JOHANNES VAN HOVE (The Hague 1790 – the Hague 1880)

BARTHOLOMEUS JOHANNES VAN HOVE (The Hague 1790 – The Hague 1880) De Grote Houtpoort, Haarlem signed on the boat in the lower right B. VAN HOVE oil on panel 1 19 /8 x 26 inches (48.6 x 66 cm.) PROVENANCE Lady V. Braithwaite Lady V. Braithwaite, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Paintings and Drawings, Sotheby’s, London, May 17, 1967, lot 90, where bought by M. Newman, Ltd., London Frost & Reed Ltd., London Vixseboxse Art Galleries, Inc., Cleveland Heights, Ohio Private Collection, Ohio, until 2015 LITERATURE The Connoisseur, volume 166, September 1967, p. XLIV, in an advertisement for M. Newman, Ltd., London, reproduced E. Bénézit, “Bartholomeus-Johannes van Hove” in Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs, volume 5, Libraire Gründ, Paris, 1976, p. 634 In a large panel, under radiant skies, the old fortifications of Haarlem abut the Spaarne River. The Grote Houtpoort rises majestically in the foreground, dominating the scene with its weathervane reaching to the composition’s edge. The Kalistoren Tower, used for the storage of gunpowder, is in the middle with the Kleine Houtpoort visible in the distance. Built in 1570, the Grote Houtpoort was at the end of the Grote Houtstraat, one of the main roads from the Grote Markt that led outside the city walls. Beyond the gate lay the wooded area, called the Haarlemmerwoud. The temperature is mild, over the arched bridge of the Grote Houtpoort, residents contentedly stroll, conversed or stop to admire the view. Below boatmen propel their craft across glass-like waters with shimmering reflections and floating swans. The sense of well-being pervades this orderly view of the city’s great landmarks that dominate its skyline. -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995. Waanders, Zwolle 1995 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012199501_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 6 Director's Foreword The Van Gogh Museum shortly after its opening in 1973 For those of us who experienced the foundation of the Van Gogh Museum at first hand, it may come as a shock to discover that over 20 years have passed since Her Majesty Queen Juliana officially opened the Museum on 2 June 1973. For a younger generation, it is perhaps surprising to discover that the institution is in fact so young. Indeed, it is remarkable that in such a short period of time the Museum has been able to create its own specific niche in both the Dutch and international art worlds. This first issue of the Van Gogh Museum Journal marks the passage of the Rijksmuseum (National Museum) Vincent van Gogh to its new status as Stichting Van Gogh Museum (Foundation Van Gogh Museum). The publication is designed to both report on the Museum's activities and, more particularly, to be a motor and repository for the scholarship on the work of Van Gogh and aspects of the permanent collection in broader context. Besides articles on individual works or groups of objects from both the Van Gogh Museum's collection and the collection of the Museum Mesdag, the Journal will publish the acquisitions of the previous year. Scholars not only from the Museum but from all over the world are and will be invited to submit their contributions. -

Vincent Van Gogh: How His Life Influenced His Orksw

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 1970 Vincent Van Gogh: How His Life Influenced His orksW Paula Herrin Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Herrin, Paula, "Vincent Van Gogh: How His Life Influenced His orks"W (1970). Honors Theses. 409. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/409 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vincent Van Gogh How His Life Influenced His Wor,.ks by Paula Herrin .. Honors Special Studies Presented to Miss Holiman Spring, 1970 Vincent Van Gogh--How His Life Influenced His Works Expressionism is a seeking of the artist to express elemental feelings that are inherent in a real world, The artist sees the con- flicts in nature and in the human being and tries to express this on canvas, Vincent Van Gogh, the forerunner of this movement, strove to paint what he felt and to feel what he painted, The Expressionists after him have branched out into all directions, but all of them expressed their feelings through their art,1 Vincent, the greatest and most revolutionary Dutch painter after Rembrandt, was born in Groot Zundert in the province of Noord Brabant on March 30, 1953, He was the first live child born to Anna Cornelia Carbentus Van Gogh and Theodorus Van Gogh, The second of the six child ren, Theo, was born four years later,2 The Van Gogh family history can be traced back to the sixteenth century, . -

Concept Omgevingsvisie Renkum PROJECT

Concept omgevingsvisie Renkum PROJECT Omgevingsvisie Renkum Projectnummer: SR200358 INITIATIEFNEMER Gemeente Renkum Generaal Urquhartlaan 4 6861 GG Oosterbeek OPSTELLER Gemeente Renkum, Buro SRO, Over Morgen Contactpersoon gemeente Renkum: Martijn Kok Contactpersoon Buro SRO: Krijn Lodewijks | John van de Zand Contactpersoon Over Morgen: Tjakko Dijk DATUM & STATUS CONCEPT | 31 mei 2021 2 Inhoud Hoofdstuk 1 | Inleiding 5 1.1 Wat doen we? 5 1.2 Waarom een omgevingsvisie? 5 1.3 Samenhang met andere overheden 7 1.4 Proces - in samenspraak 8 Hoofdstuk 2 | Renkum in 2021 9 2.1 Historische ontwikkeling 9 2.2 Regionale context & profilering 9 2.3 Kenmerken en kwaliteiten – gemeentebreed 9 2.4 Uitgelicht: Het landschap van Renkum 11 2.5 Uitgelicht: De dorpen van Renkum 12 Hoofdstuk 3 | Huidige ontwikkelingen 15 3.1 Renkum Samen 15 3.2 Renkum Gezond en Leefbaar 15 3.3 Renkum Toekomstbestendig 16 3.4 Renkum Dynamisch 17 Hoofdstuk 4 | Renkum in 2040 19 4.1 Regionale positionering 19 4.2 Renkum Samen 20 4.3 Renkum Gezond en Leefbaar 21 4.4 Renkum Toekomstbestendig 25 4.5 Renkum dynamisch 28 4.6 Uitgelicht: Het landschap van Renkum 29 4.7 Uitgelicht: De dorpen van Renkum 34 Hoofstuk 5 | De visie samen waarmaken 49 5.1 Inleiding 49 5.2 Beleidscyclus 49 5.3 Strategische uitvoeringsagenda - mogelijke programma’s voor uitvoering 50 5.4 Een flexibele en adaptieve omgevingsvisie 50 5.5 Participatie bij de uitvoering van de omgevingsvisie 51 5.6 Toetsingskader voor de initiatieven vanuit de samenleving 52 BIJLAGE 1 | Renkum anno 2021 56 3 4 Hoofdstuk 1 | Inleiding een visie voor de gemeente Renkum in 2040 1.1 Wat doen we? kijk nodig is. -

Los Genios Del Postimpresionismo II VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853 – 1890)

Los genios del Postimpresionismo II VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853 – 1890) La Familia Van Gogh Biografía • Vincent nace en Groot – Zundert (Brabante) • Familia burguesa, su padre Theodorus es pastor calvinista • ETAPA LONDINENSE. Hermanos marchantes de arte, primeros contactos para Vincent, trabajando para Los Goulpin. Inicia su gusto por la pintura y la literatura. Primeros desengaños amorosos, se vuelve taciturno y violento. Fuerte carácter que le llevará al despido y el desengaño de su familia. • ETAPA EN ÁMSTERDAM. Período de espiritualidad, se forma como pastor para cuidar y consolar a pobres y desgraciados. Fracasa al suspender exámenes del seminario. • ETAPA EN BORINAGE. Se instala en esta aldea sacrificándose por los pobres y viviendo de manera miserable. Acuden en su ayuda su hermano Théo y su tío Anton Mauve. LA HAYA (1882 – 1886) • 1882: decide dedicarse a la pintura y se traslada a La Haya, al taller de Anton Mauve. Etapa de formación y primeros dibujos y lienzos. • Por diferencias estilísticas romperá su relación con Mauve y malvivirá con lo que Théo envía desde París. • Vive en suburbios y conoce a Christine, prostituta que recogerá embarazada en la calle y mantendrá a cambio de que se convierta en su modelo. • Influencias: – Toma contacto con los paisajistas holandeses. – Se atrae por la pintura de Corot y Millet. • Busca pintar al ser humano desfavorecido, pobre, la miseria • ARTE COMO SALVACIÓN: lugar donde expresar los sentimientos religiosos y sociales Los comedores de patatas (1885) Museo Van Gogh, Ámsterdam PARÍS (1886 – 1888) • 1886: tras su formación en La Haya decide trasladarse al apartamento parisino de Théo, vivirá dos años en el. -

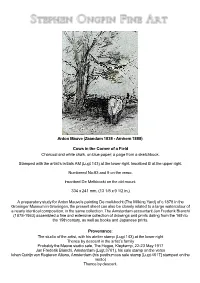

Cows in the Corner of a Field Charcoal and White Chalk, on Blue Paper; a Page from a Sketchbook

Anton Mauve (Zaandam 1838 - Arnhem 1888) Cows in the Corner of a Field Charcoal and white chalk, on blue paper; a page from a sketchbook. Stamped with the artist’s initials AM (Lugt 143) at the lower right. Inscribed B at the upper right. Numbered No:83 and 9 on the verso. Inscribed De Melkbockt on the old mount. 334 x 241 mm. (13 1/8 x 9 1/2 in.) A preparatory study for Anton Mauve's painting De melkbocht (The Milking Yard) of c.1878 in the Groninger Museum in Groningen, the present sheet can also be closely related to a large watercolour of a nearly identical composition, in the same collection. The Amsterdam accountant Jan Frederik Bianchi (1878-1963) assembled a fine and extensive collection of drawings and prints dating from the 16th to the 19th century, as well as books and Japanese prints. Provenance: The studio of the artist, with his atelier stamp (Lugt 143) at the lower right Thence by descent in the artist’s family Probably the Mauve studio sale, The Hague, Kleykamp, 22-23 May 1917 Jan Frederik Bianchi, Amsterdam (Lugt 3761), his sale stamp on the verso Iohan Quirijn van Regteren Altena, Amsterdam (his posthumous sale stamp [Lugt 4617] stamped on the verso) Thence by descent. Artist description: Anthonij (Anton) Mauve studied in Haarlem with the animal painters Wouter Verschuur and Pieter Frederik van Os, and in the summer of 1858 paid the first of several visits to the artist’s colony at Oosterbeek, in the province of Gelderland. In his early work Mauve concentrated on paintings of cows in a landscape, although he also painted horses and, later, sheep and shepherds, for which he became best known. -

Master Education in Arts

Course title Art 160: Dutch Art and Architecture (3 credits) Course description Introduction to the history of Dutch Art and Architecture, from the Middle Ages to the Present day. The program contains a lot of excursions to view the various artworks ’live’. The program will bring insight in how to look at art and how the Dutch identity is reflected in artworks and the importance of the works in culture and history. This will be achieved by presentations of classmates, lectures, reading and fieldtrips. Instructor: Ludie Gootjes-Klamer Artist and Master Education in Arts. Textbooks Reader: Introduction to Dutch Art and Architecture by Ludie Gootjes- Klamer Students learning Goals and Objectives Goals 1. Insight in Dutch Art and Architecture 2. Learning in small groups 3. Use the ‘Looking at art’ method. 4. Practise in giving an interesting, informing and appealing presentation to classmates. 5. Essay writing. 6. Reflect on artworks and fieldtrips Objectives - Dutch Old masters (such as Rembrandt, Frans Hals, and Vermeer.) - Building styles (Roman, Gothic, Nieuwe Bouwen, Berlage.) - Cobra movement (Appel, Corneille, Lucebert) - De Stijl ( Rietveld, Mondriaan) - Temporary Artists Methods 1. Lectures 2. Excursions 3. Reading 4. Presentations by the students for their classmates. 5. Essay writing Class Attendance an Participation Minimal 90% Attendance. Participation in excursions and presentation in small groups are mandatory. Written reflections on excursion and presentations are mandatory. Examination First and Final impression(A) 0,5 Essay (B) 0,5 Presentation (C) 0,5 Reflection on Fieldtrips (D) 0,5 Final Exam (E) 1 -------------------------------------- 3 ECTS Tentative Course Outline Week 4 20 jan. Lecture and excursion Zwolle Week 5 30 jan.