Vol. 45, No. 1: Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuremberg Revisited in Burma? an Assessment of the Potential Liability of Transnational Corporations and Their Officials in Burma Under International Criminal Law

NUREMBERG REVISITED IN BURMA? AN ASSESSMENT OF THE POTENTIAL LIABILITY OF TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATIONS AND THEIR OFFICIALS IN BURMA UNDER INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW By Mary Ann Johnson Navis A dissertation submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Victoria University of Wellington 2010 1 ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the role played by officials of transnational corporations and transnational corporations themselves in the situation in Burma. The main aim of this dissertation is to assess the liability of officials of transnational corporations in Burma and transnational corporations in Burma for crimes against humanity such as slave labour and for war crimes such as plunder under International Criminal Law. However at present transnational corporations cannot be prosecuted under International Criminal Law as the International Criminal Court only has jurisdiction to try natural persons and not legal persons. In doing this analysis the theory of complicity, actus reus of aiding and abetting and the mens rea of aiding and abetting in relation to officials of transnational corporations will be explored and analysed to assess the liability of these officials in Burma. In doing this analysis the jurisprudence of inter alia the Nuremberg cases, the cases decided by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) will be used. This dissertation also examines the problems associated with suing or prosecuting transnational corporations due to the legal personality of transnational corporations and the structure of transnational corporations. At the end of the dissertation some recommendations are made so as to enable transnational corporations to be more transparent and accountable under the law. -

Karl Heinz Roth Die Geschichte Der IG Farbenindustrie AG Von Der Gründung Bis Zum Ende

www.wollheim-memorial.de Karl Heinz Roth Die Geschichte der I.G. Farbenindustrie AG von der Gründung bis zum Ende der Weimarer Republik Einleitung . 1 Vom „Dreibund“ und „Dreierverband“ zur Interessengemeinschaft: Entwicklungslinien bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs . 1 Der Weg zurück zum Weltkonzern: Die Interessengemeinschaft in der Weimarer Republik . 9 Kehrtwende in der Weltwirtschaftskrise (1929/30–1932/33) . 16 Norbert Wollheim Memorial J.W. Goethe-Universität / Fritz Bauer Institut Frankfurt am Main 2009 www.wollheim-memorial.de Karl Heinz Roth: I.G. Farben bis zum Ende der Weimarer Republik, S. 1 Einleitung Zusammen mit seinen Vorläufern hat der I.G. Farben-Konzern die Geschichte der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts in exponierter Stellung mitgeprägt. Er be- herrschte die Chemieindustrie Mitteleuropas und kontrollierte große Teile des Weltmarkts für Farben, Arzneimittel und Zwischenprodukte. Mit seinen technolo- gischen Innovationen gehörte er zu den Begründern des Chemiezeitalters, das die gesamte Wirtschaftsstruktur veränderte. Auch die wirtschaftspolitischen Rahmenbedingungen gerieten zunehmend unter den Einfluss seiner leitenden Manager. Im Ersten Weltkrieg wurden sie zu Mitgestaltern einer aggressiven „Staatskonjunktur“, hinter der sich die Abgründe des Chemiewaffeneinsatzes, der Kriegsausweitung durch synthetische Sprengstoffe, der Ausnutzung der Annexi- onspolitik und der Ausbeutung von Zwangsarbeitern auftaten. Nach dem Kriegs- ende behinderten die dabei entstandenen Überkapazitäten die Rückkehr zur Frie- denswirtschaft -

I.G. Farben's Petro-Chemical Plant and Concentration Camp at Auschwitz Robert Simon Yavner Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Summer 1984 I.G. Farben's Petro-Chemical Plant and Concentration Camp at Auschwitz Robert Simon Yavner Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the Economic History Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Yavner, Robert S.. "I.G. Farben's Petro-Chemical Plant and Concentration Camp at Auschwitz" (1984). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, History, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/7cqx-5d23 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds/27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1.6. FARBEN'S PETRO-CHEMICAL PLANT AND CONCENTRATION CAMP AT AUSCHWITZ by Robert Simon Yavner B.A. May 1976, Gardner-Webb College A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 1984 Approved by: )arw±n Bostick (Director) Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Copyright by Robert Simon Yavner 1984 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT I.G. FARBEN’S PETRO-CHEMICAL PLANT AND CONCENTRATION CAMP AT AUSCHWITZ Robert Simon Yavner Old Dominion University, 1984 Director: Dr. Darwin Bostick This study examines the history of the petro chemical plant and concentration camp run by I.G. -

The Persistence of Elites and the Legacy of I.G. Farben, A.G

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-7-1997 The Persistence of Elites and the Legacy of I.G. Farben, A.G. Robert Arthur Reinert Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Reinert, Robert Arthur, "The Persistence of Elites and the Legacy of I.G. Farben, A.G." (1997). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5302. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Robert Arthur Reinert for the Master of Arts in History were presented May 7, 1997, and accepted by the thesis committee and department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Sean Dobson, Chair ~IReard~n Louis Elteto Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: [)fl Dodds Department of History * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY by on ct</ ~~ /997 ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Robert Arthur Reinert for the Master of Arts in History presented May 7, 1997. Title: The Persistence of Elites and the Legacy of LG. Farben, A.G .. On a massive scale, German business elites linked their professional ambitions to the affairs of the Nazi State. By 1937, the chemical giant, l.G. Farben, became completely "Nazified" and provided Hitler with materials which were essential to conduct war. -

Prominent Nazi Lawyer – and Key Architect of the 'Brussels

Master Plan of the Nazi/Cartel Coalition – Blueprint for the ‘Brussels EU’ Chapter 2 WALTER HALLSTEIN: Prominent Nazi Lawyer – And Key Architect of the ‘Brussels EU’ Chapter 2 Walter Hallstein (1901-1982) Walter Hallstein was a prominent lawyer involved in the legal and ad- ministrative planning for a post-WWII Europe under the control of the Nazis and their corporate allies, the Oil and Drug Cartel IG Far- ben. Hallstein represented the new breed of members of the Nazi/Cartel Coalition. He was trained by legal teachers whose primary goal was to sabotage the ‘Versailles Treaty’ defining the reparation payments imposed on Germany after it lost WWI. Early on in his career Hall- stein received a special training at the ‘Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin.’ This private institute was largely financed by the IG•Farben Cartel to raise its scientific and legal cadres for the Cartel’s next at- tempts at the conquest and control of Europe and the world. While the rule of the Nazis ended in 1945, the rule of their accom- plices, the IG Farben Cartel and its successors BAYER, BASF, and HOECHST had just begun. As a strategic part of their plan to launch the third attempt at the conquest of Europe, they placed – a mere decade after their previous attempt had failed – one of their own at the helm of the new cartel ‘politburo’ in Brussels: Walter Hallstein. This chapter documents that the fundamentally undemocratic con- struct of today’s ‘Brussels EU’ is no coincidence. Hallstein, a promi- nent Nazi lawyer – and expert on the IG•Farben concern – was chosen by these corporate interests to become the first EU Commission pres- ident with a specific assignment: to model the ‘Brussels EU’ after the original plans of the Nazi/IG Farben coalition to rule Europe through a ‘Central Cartel Office’. -

Military Tribunal, Indictments

MILITARY TRIBUNALS CASE No.6 THE UNITED STATES OK AMERICA -against- CARL KRAUCH, HERMANN SCHMITZ, GEORG VON SCHNITZLER, FRITZ GAJEWSKI, HEINRICH HOERLEIN, AUGUST VON KNIERIEM, FRITZ.a'ER MEER, CHRISTIAN SCHNEIDER, OTTO AMBROS, MAX BRUEGGEMANN, ERNST BUERGIN, HEINRICH BUETEFISCH, PAUL HAEFLIGER, MAX ILGNER, FRIEDRICH JAEHNE,. HANS KUEHNE, CARL LAUTENSCHLAEGER, WILHELM MANN, HEINRICH OSTER, KARL WURSTER, WALTER DUERR FELD, HEINRICH GATTINEAU, ERICH VON DER HEYDE, and HANS KUGLER, officialS of I. G. F ARBENINDUSTRIE AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT Defendants OFFICE OF MILITARY GOVERNMENT FOR GERMANY (US) NURNBERG 1947 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/1e951a/ 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/1e951a/ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY 5 COUNT ONE-PLANNING, PREPARATION, INITIATION AND WAGING OF WARS OF AGGRESSION AND INVASIONS OF OTHER COUNTRIES 9 STATEMENT OF THE OFFENSE 9 PARTICULARS OF DEFENDANTS' PARTICIPATION 9 A. The Alliance of FARBEN with Hitlet· and the Nazi Party 9 B. F ARBEN synchronized all of its activities with the military planning of the German High Command 13 C. FARBEN participated in preparing the Four Year Plan and in directing the economic mobilization of Germany for war 15 D. F ARBEN participated in creating and equipping the Nazi military machine for aggressive war. 20 E. F ARB EN procured and stockpiled critical war materials . for the Nazi offensive / 22 F. FARBEN participated in weakening Germany's potential enemies 23 G. FARBEN carried on propaganda, intelligence, and espionage activ:ities 25 H. With the approach of war and with each new act of aggression, F ARBEN intensified its preparation for, and participation in, the planning and execution of such aggressions and the reaping of spoils therefrom 27 I. -

BULETINUL SOCIETĂŢII DE CHIMIE DIN ROMÂNIA FONDATĂ ÎN 1919 Nr

BULETINUL SOCIETĂŢII DE CHIMIE DIN ROMÂNIA FONDATĂ ÎN 1919 Nr. XX (serie nouă) 3/ 2013 2 1 3 5 4 6 In memoriam Prof.dr.doc. Eugen Segal Instituții de învățământ superior cu profil de chimie din România– Facultatea de Inginerie alimentară, turism și protecția mediului - Universitatea “Aurel Vlaicu“ din Arad Centenarul sintezei industriale a amoniacului The 18th Romanian International Conference on Chemistry and Chemical Engineering-RICCCE18, Sinaia 2013 Un regal al Științei în România: Frontiers in Macromolecular and Supramolecular Science – Simpozionul Cristofor I. Simionescu Societatea de Chimie din România Romanian Chemical Society Universitatea POLITEHNICA din Bucureşti, Departamentul de Chimie organică Costin NENIȚESCU Splaiul Independenței 313, tel/fax +40 1 3124573 Bucureşti, România BULETINUL Societății de Chimie din România 3/2013 COLEGIUL EDITORIAL: Coordonator: Eleonora-Mihaela UNGUREANU Membri: Marius ANDRUH, Petru FILIP, Lucian GAVRILĂ, Horia IOVU, Ana Maria JOŞCEANU, Mircea MRACEC, Aurelia BALLO, Ana-Maria ALBU 2 Buletinul S. Ch. R. Nr. XX, 3/2013 Copyright 2013, Societatea de Chimie din România. Toate drepturile asupra acestei ediții sunt rezervate Societății de Chimie din România Adresa redacției: Universitatea POLITEHNICA din Bucureşti, Facultatea de Chimie Aplicată şi Ştiința Materialelor, Str. Gh. Polizu 1-7, corp E, etaj 2, Cod 011061; Tel: 4021 402 39 77; e-mail: [email protected] Coperta 1 1. Prof. Dr. Doc. Eugen Segal- In memoriam 2. Universitatea “AUREL VLAICU“ din Arad (UAV) 3. Laboratorul de evaluarea şi controlul calităţii mediului din UAV 4. Imagini din timpul conferinţei internaţionale de chimie şi inginerie chimică RICCCE XVIII, 2013 5. Profesorul Cristofor I. Simionescu 6. Afişul Simpozionului internațional Cristofor I. -

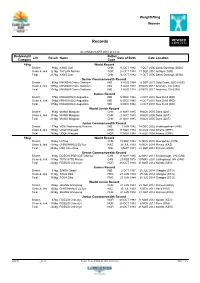

Records 9 APR 23:12

Weightlifting Women REVISED Records 9 APR 23:12 As of MON 9 APR 2018 at 23:12 Bodyweight Nation Lift Result Name Date of Birth Date Location Category Code 48kg World Record Snatch 98kg YANG Lian CHN 16 OCT 1982 1 OCT 2006 Santo Domingo (DOM) Clean & Jerk 121kg TAYLAN Nurcan TUR 29 OCT 1983 17 SEP 2010 Antalya (TUR) Total 217kg YANG Lian CHN 16 OCT 1982 1 OCT 2006 Santo Domingo (DOM) Senior Commonwealth Record Snatch 85kg MIRABAI Chanu Saikhom IND 8 AUG 1994 5 SEP 2017 Gold Coast, QLD (AUS) Clean & Jerk 109kg MIRABAI Chanu Saikhom IND 8 AUG 1994 29 NOV 2017 Anaheim, CA (USA) Total 194kg MIRABAI Chanu Saikhom IND 8 AUG 1994 29 NOV 2017 Anaheim, CA (USA) Games Record Snatch 77kg NWAOKOLO Augustina IND 12 DEC 1982 4 OCT 2010 New Dehli (IND) Clean & Jerk 98kg NWAOKOLO Augustina IND 12 DEC 1982 4 OCT 2010 New Dehli (IND) Total 175kg NWAOKOLO Augustina IND 12 DEC 1982 4 OCT 2010 New Dehli (IND) World Junior Record Snatch 95kg WANG Mingjuan CHN 21 MAY 1985 9 NOV 2005 Doha (QAT) Clean & Jerk 118kg WANG Mingjuan CHN 21 MAY 1985 9 NOV 2005 Doha (QAT) Total 213kg WANG Mingjuan CHN 21 MAY 1985 9 NOV 2005 Doha (QAT) Junior Commonwealth Record Snatch 77kg VENI Neelamsetty Krishna IND 1 JAN 1982 14 DEC 2002 Visakhapatnam (IND) Clean & Jerk 105kg UDOH Blessed NGR 17 NOV 1984 14 AUG 2004 Athens (GRE) Total 180kg UDOH Blessed NGR 17 NOV 1984 14 AUG 2004 Athens (GRE) 53kg World Record Snatch 103kg LI Ping CHN 15 SEP 1988 14 NOV 2010 Guangzhou (CHN) Clean & Jerk 134kg CHINSHANLO Zulfiya KAZ 25 JUL 1993 10 NOV 2014 Almaty (KAZ) Total 233kg HSU Shu-ching TPE -

PDF Printing 600

I.G.FARBEN" INDUSTRIE AKTIEN GESELLSCHAFT FRANKFURT (J\\AIN) 1 9 4 0 I. G. Farbenindustrie Aktiengesellschaft Frankfurt am Main Bericht des Vorstands und des Aufsichtsrats und Jahresabschluß für das Geschäftsjahr 1940. In Ehrfurcht und Dankbarkeit gedenken wir unserer Kameraden, die ihr Leben im Kampf um die Verteidigung unseres Vaterlandes hingegeben haben. 16. ordentliche Hauptversammlung Freitag, den 8. August 1941, vormittags 11 Uhr, in unseremVerwaltungsgebäude Frankfurt am Main, Grüneburgplatz. Tagesordnung: 1. Vorlage des Jahresabschlusses und des Geschäftsberichts für 1940 mit dem Prüfungs• bericht des Aufsichtsrats und Beschlußfassung über die Gewinnverteilung. 2. Entlastung von Vorstand und Aufsichtsrat. 3. Ermächtigung des Vorstands bis zum 1. August 1946 zur Erhöhung des Grund kapitals um bis RM 100000000.- durch Ausgabe neuer Stammaktien gegen Geld oder Sacheinlagen (genehmigtes Kapital). Änderung des § 6 der Satzung. 4. Wahlen zum Aufsichtsrat. 5. Wahl des Abschlußprüfers für das Geschäftsjahr 1941. VORSTAND. Geheimer Kommerzienrat Dr. HER M AN N SC H M IT Z, Ludwigshafen a. Rh./Heidelberg, Vorsitzer, Dr. FRITZ GAJEWSKI, Leipzig, Professor Dr. HEINRICH HÖRLEIN, Wuppertal-Elberfeld, Dr. AUGUST v. KNIERIEM, Mannheim, Zentralausschuß Dr. FRITZ TER MEER, Kronberg (Taunus), Dr. CHRISTIAN SCHNEIDER, Leuna, Dr. GEORG von SCHNITZLER, Frankfurt am Main, Dr. OTTO AMBROS, Ludwigshafen a. Rh., Dr. MAX BRÜGGEMANN, Käln-Marienburg, Dr. ERNST BÜRGIN, Bitterfeld, Dr. HEINRICH BÜTEFISCH, Leuna, PAUL HAEFLIGER, Frankfurt am Main, Dr. MAX JLGNER, Berlin-Steglitz, Dr. CONSTANTIN JACOBI, Frankfurt am Main, Dip!. Ing. FRIEDRICH JÄHNE, Frankfurt am Main, Dr. HANS KÜHNE, Leverkusen-LG. Werk, Professor Dr. CARL LUDWIG LAUTENSCHLÄGER, Frankfurt am Main, Generalkonsul WILHELM RUDOLF MANN, Berlin-Grunewald, Dr. HEINRICH OSTER, Berlin-Charlottenburg, Kommerzialrat WILHELM OTTO, Berlin-Zehlendorf-West, Dr. -

![[Pdf] Florian Schmaltz the Bunamonowitz Concentration Camp](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6305/pdf-florian-schmaltz-the-bunamonowitz-concentration-camp-2286305.webp)

[Pdf] Florian Schmaltz the Bunamonowitz Concentration Camp

www.wollheim-memorial.de Florian Schmaltz The Buna/Monowitz Concentration Camp The Decision of I.G. Farbenindustrie to Locate a Plant in Auschwitz . 1 The Buna ―Aussenkommando‖ (April 1941 to July 1942) . 10 The Opening of the Buna/Monowitz Camp – Demographics of the Prisoner Population . 15 Composition of the Prisoner Groups in Monowitz . 18 The Commandant of Buna/Monowitz . 19 The Administrative Structure of the Camp . 21 Guard Forces . 24 The Work Deployment of the Prisoners . 25 Casualty Figures . 28 The Camp Elders . 35 Escape and Resistance . 36 Air Attacks on Auschwitz . 38 The Evacuation of the Camp . 42 Norbert Wollheim Memorial J.W. Goethe-Universität / Fritz Bauer Institut Frankfurt am Main, 2010 www.wollheim-memorial.de Florian Schmaltz: The Buna/Monowitz Concentration Camp, p. 1 The Decision of I.G. Farbenindustrie to Locate a Plant in Auschwitz The Buna/Monowitz concentration camp, which was erected by the SS in October 1942, was the first German concentration camp that was located on the plant grounds of a major private corporation.1 Its most important function was the fur- nishing of concentration camp prisoners as slave laborers for building the I.G. Auschwitz plant, I.G. Farben‘s largest construction site. Instead of estab- lishing an industrial production location on the grounds of an existing concentra- tion camp, a company-owned branch camp of a concentration camp was put up here, for the first time, on a site belonging to an arms manufacturer. This new procedure for construction of the I.G. Auschwitz plant served as a model and in- fluenced the subsequent collaboration between the arms industry and the SS in the process of expanding the concentration camp system in Nazi territory throughout Europe, particularly toward the end of the war, when numerous sub- camps were established in the course of shifting industrial war production to un- derground sites.2 The Buna/Monowitz concentration camp was located in East Upper Silesia within the western provinces of Poland, which had been annexed by the German Reich. -

Weightlifting ウエイトリフティング Haltérophilie

Start List Package スタートリストパッケージ Set de listes de départ Weightlifting ウエイトリフティング Haltérophilie Tokyo International Forum 東京国際フォーラム Tokyo International Forum WLF-------------------------------_B51_20210722 V1 Report Created THU 22 JUL 2021 15:31 Tokyo International Forum Weightlifting ウエイトリフティング / Haltérophilie Timetable As of THU 22 JUL 2021 G r o u p s o f O f f i c i a l s Start Gender Cat. Group Date Athletes Chief Tech. Time TD Jury Referee Marshal Timekeeper Contrl. Doctor Secr. 1 Women 49 B SAT 24 JUL 09:50 6 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 Women 49 A SAT 24 JUL 13:50 8 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 Men 61 B SUN 25 JUL 11:50 5 1 2 3 2 2 3 2 2 4 Men 67 B SUN 25 JUL 11:50 4 1 2 3 2 2 3 2 2 5 Men 61 A SUN 25 JUL 15:50 9 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 Men 67 A SUN 25 JUL 19:50 10 1 1 2 1 2 2 1 1 7 Women 55 B MON 26 JUL 13:50 5 1 1 3 1 2 3 1 1 8 Women 55 A MON 26 JUL 19:50 9 1 2 1 2 1 1 2 2 9 Women 59 B TUE 27 JUL 11:50 5 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 10 Women 64 B TUE 27 JUL 11:50 4 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 11 Women 59 A TUE 27 JUL 15:50 9 1 1 3 1 2 3 1 1 12 Women 64 A TUE 27 JUL 19:50 10 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 13 Men 73 B WED 28 JUL 13:50 5 1 1 2 1 2 2 1 1 14 Men 73 A WED 28 JUL 19:50 9 1 2 3 2 2 3 2 2 REST DAY THU 29 JUL REST DAY FRI 30 JUL 15 Men 81 B SAT 31 JUL 11:50 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 16 Men 96 B SAT 31 JUL 11:50 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 17 Men 81 A SAT 31 JUL 15:50 10 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 18 Men 96 A SAT 31 JUL 19:50 10 1 2 3 2 2 3 2 2 19 Women 76 B SUN 1 AUG 13:50 6 1 2 1 2 1 1 2 2 20 Women 76 A SUN 1 AUG 19:50 8 1 1 2 1 2 2 1 1 21 Women 87 B MON 2 AUG 11:50 5 1 1 3 1 2 3 1 1 22 Women +87 B MON 2 AUG 11:50 4 1 1 3 1 2 3 1 1 23 Women 87 A MON 2 AUG 15:50 9 1 2 1 2 1 1 2 2 24 Women +87 A MON 2 AUG 19:50 10 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 25 Men 109 B TUE 3 AUG 13:50 5 1 2 3 2 2 3 2 2 26 Men 109 A TUE 3 AUG 19:50 9 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 27 Men +109 B WED 4 AUG 13:50 6 1 1 2 1 2 2 1 1 28 Men +109 A WED 4 AUG 19:50 8 1 2 3 2 2 3 2 2 Note: Typical duration of a competition with 10 athletes is usually 2 hours including the Victory Ceremony. -

Historical Review of Developments Relating to Aggression

Historical Review of Developments relating to Aggression United Nations New York, 2003 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.03.V10 ISBN 92-1-133538-8 Copyright 0 United Nations, 2003 All rights reserved Contents Paragraphs Page Preface xvii Introduction 1. The Nuremberg Tribunal 1-117 A. Establishment 1 B. Jurisdiction 2 C. The indictment 3-14 1. The defendants 4 2. Count one: The common plan or conspiracy to commit crimes against peace 5-8 3 3. Count two: Planning, preparing, initiating and waging war as crimes against peace 9-10 4. The specific charges against the defendants 11-14 (a) Count one 12 (b) Counts one and two 13 (c) Count two 14 D. The judgement 15-117 1. The charges contained in counts one and two 15-16 2. The factual background of the aggressive war 17-21 3. Measures of rearmament 22-23 4. Preparing and planning for aggression 24-26 5. Acts of aggression and aggressive wars 27-53 (a) The seizure of Austria 28-31 (b) The seizure of Czechoslovakia 32-33 (c) The invasion of Poland 34-35 (d) The invasion of Denmark and Norway 36-43 Paragraphs Page (e) The invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg 44-45 (f) The invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece 46-48 (g) The invasion of the Soviet Union 49-51 (h) The declaration of war against the United States 52-53 28 6. Wars in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances 54 7. The Law of the Charter 55-57 The crime of aggressive war 56-57 8.