Birthing Washington: Objects, Memory, and the Creation of a National Monument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popes Creek Trail Concept Presented

Popes Creek Trail concept presented Posted by TBN_Charles On 06/22/2017 La Plata, MD - The Pope’s Creek Rail Trail is moving forward. Eileen Minnick, Charles County director of recreation, told the Charles County Commissioners Tuesday, June 20 that barring any hiccups along the way, construction on the new trail could begin as early as next summer. In January 2014, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources was awarded a $1 million federal grant to preserve 220 acres of the Popes Creek watershed. The thought was to establish a new rail trail along the abandoned Popes Creek rail bed, a distance of some two miles. “One of the goals of the county recreation and parks and tourism is water access,” said Parks Director Jon Snow. “It’s a real challenge to get waterfront access.” Snow said the county is adding boat ramps and kayak launches at Port Tobacco River Park and Chapel Point. “Everyone in Charles County wants it, but not everyone is a boater,” Snow said. “But they still want water access. These projects will do a really good job of providing that. “Popes Creek is one of our best opportunities for waterfront access,” he added. “We’ve got a really good opportunity to create a water access venue on and off the water. Steve Engle of Vista Design Inc. outlined a conceptual plan for the trail, which includes an elevated observation platform over the Potomac River and a possible museum at the site of the old Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative power plant at Popes Creek, built in 1938. -

Key Facts About Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis Families

Key Facts about Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis families. The George Washington Foundation The Foundation owns and operates Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore. The Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. The Foundation (then known as the Kenmore Association) was formed in 1922 in order to purchase Kenmore. The Foundation purchased Ferry Farm in 1996. Historic Kenmore Kenmore was built by Fielding Lewis and his wife, Betty Washington Lewis (George Washington’s sister). Fielding Lewis was a wealthy merchant, planter, and prominent member of the gentry in Fredericksburg. Construction of Kenmore started in 1769 and the family moved into their new home in the fall of 1775. Fielding Lewis' Fredericksburg plantation was once 1,270 acres in size. Today, the house sits on just one city block (approximately 3 acres). Kenmore is noted for its eighteenth-century, decorative plasterwork ceilings, created by a craftsman identified only as "The Stucco Man." In Fielding Lewis' time, the major crops on the plantation were corn and wheat. Fielding was not a major tobacco producer. When Fielding died in 1781, the property was willed to Fielding's first-born son, John. Betty remained on the plantation for another 14 years. The name "Kenmore" was first used by Samuel Gordon, who purchased the house and 200 acres in 1819. Kenmore was directly in the line of fire between opposing forces in the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862 during the Civil War and took at least seven cannonball hits. Kenmore was used as a field hospital for approximately three weeks during the Civil War Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. -

Museum of M()Dern Art , Su M Mer

'MUSEUM OF M()DERN ART . ~ , SU M MER E X H I~B"I·T;'I-O·N .. «' - ....,.- '"' ~'''", . .,~.~ ". , -, ,~ _ '\ c - --7'-"-....;:;.:..,:· ........ ~~., - ", -,'" ,""" MoMAExh_0007_MasterChecklist , , . ,. • •• ' ,A· . -" . .t, ' ." . , , ,.R'ET-ROSPECTIVE .. , . .... ~,~, , ....., , .' ~ ,,"• ~, ~.. • • JUNE 1930 SEPTEMBER 730 FIFTH AVENUE · NEW YORK J ( - del SCULPTURE : , Rudolf Bdling I MAX SCHMELING (Bronze) Born, 1886 Berlin. Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Alfred Flechtheim, Berlin CItarl~s D~spiau 2. HEADOFMARIALANI(Bro11ze) Born 1874. .. Collection Museum of Modern Art, New Yark Mont de Marsan, France. Gift of Miss L. P. Bliss WilIt~lm L~Itmf:,ruck >0. 0S~FIGUREOFWO¥AN(Stollt) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Born 1881. Germany. Private Collection, New York Died 1919. 4 STANDING WOMAN (Bro11ze) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York MoMAExh_0007_MasterChecklist Gifr of Stephen C. Clark Aristid~ MaiUo! 5 DESIRE (Plaster relief) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Born 1861 in southern France. Collection Museum of Modern Arr, New York Gift of the Sculptor. 6 SPRING (Plaster) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York Gifr of the Sculptor. 7 SUMMER (Plaster) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of the Sculptor. 8 TORSO OF A YOUNG WOMAN (Bro11ze) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of A. Conger Goodyear PAINTING P~t~rBlum~ ~ 0 , ~.:s-o 9 PARADE PREVIOUSLY EXHIDITED Born 1906, Russia. Private Collection, New York G~org~s Braqu~ /:5 0 • b0 '3 10 LE COMPOTIER ET LA SERVIETTE Born 1881. Argenteuil. " Collection Frank Crowninshield, New York 0 , " 0 '" II STIlL LIFE I'?> J Collection Frank Crowninshield, New York ~ 0 bUb 12. PEARS, PIPE AND PITCHER ~ I Collection Phillips Memorial Gallery, Washington 3 I L 13D,iQa,13 FALLEN TREE PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Born 1893, Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio. -

Carlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’S Elusive Spinet - the Washington Connection by Richard Klingenmaier

The Friends of Carlyle House Newsletter Spring 2017 “It’s a fine beginning.” CarlyleCarlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s Elusive Spinet - The Washington Connection By Richard Klingenmaier “My Sally is just beginning her Spinnet” & Co… for Miss Patsy”, dated October 12, 1761, George John Carlyle, 1766 (1) Washington requested: “1 Very good Spinit (sic) to be made by Mr. Plinius, Harpsichord Maker in South Audley Of the furnishings known or believed to have been in John Street Grosvenor Square.” (2) Although surviving accounts Carlyle’s house in Alexandria, Virginia, none is more do not indicate when that spinet actually arrived at Mount fascinating than Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s elusive spinet. Vernon, it would have been there by 1765 when Research confirms that, indeed, Sarah owned a spinet, that Washington hired John Stadler, a German born “Musick it was present in the Carlyle House both before and after Professor” to provide Mrs. Washington and her two her marriage to William Herbert and probably, that it children singing and music lessons. Patsy was to learn to remained there throughout her long life. play the spinet, and her brother Jacky “the fiddle.” Entries in Washington’s diary show that Stadler regularly visited The story of Mount Vernon for the next six years, clear testimony of Sarah Carlyle the respect shown for his services by the Washington Herbert’s family. (3) As tutor Philip Vickers Fithian of Nomini Hall spinet actually would later write of Stadler, “…his entire good-Nature, begins at Cheerfulness, Simplicity & Skill in Music have fixed him Mount Vernon firm in my esteem.” (4) shortly after George Beginning in 1766, Sarah (“Sally”) Carlyle, eldest daughter Washington of wealthy Alexandria merchant John Carlyle and married childhood friend of Patsy Custis, joined the two Custis Martha children for singing and music lessons at the invitation of Dandridge George Washington. -

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’S Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’s Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David W. Young Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Steven Conn, Advisor Saul Cornell David Steigerwald Copyright by David W. Young 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines how public history and historic preservation have changed during the twentieth century by examining the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1683, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, with resonant landmarks related to the nation’s political, military, industrial, and cultural history. Efforts to preserve the historic sites of the neighborhood have resulted in the presence of fourteen historic sites and house museums, including sites owned by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the City of Philadelphia. Germantown is also a neighborhood where many of the ills that came to beset many American cities in the twentieth century are easy to spot. The 2000 census showed that one quarter of its citizens live at or below the poverty line. Germantown High School recently made national headlines when students there attacked a popular teacher, causing severe injuries. Many businesses and landmark buildings now stand shuttered in community that no longer can draw on the manufacturing or retail economy it once did. Germantown’s twentieth century has seen remarkably creative approaches to contemporary problems using historic preservation at their core. -

The George Washington University

The George Washington University Degree Programmme Does your University accept the Yes. HKCEE grades are considered direct equivalents to GCSE HKCEE and HKALE for exams. The HKALE grades are equivalent to GCE A-level. admission to your University? What are the entry requirements HKALE grades A-C. for a student with HKCEE and HKCEE in a broad range of subjects – the majority should be grade HKALE qualifications entering A-B. your University? Do students with HKCEE and Students must take the SAT or ACT and have an official score report HKALE qualifications have to sit sent from the College Board to the George Washington University. an entrance examination to enter your University? Is there a language proficiency Students must submit an official TOEFL score (Test of English as a test that students with HKCEE Foreign Language) unless the student scores a 550 or higher on the and HKALE qualifications critical reading section of the SAT. wishing to enter your University must take? Is there a standard on an For TOEFL minimum requirements visit: international English scale that http://gwired.gwu.edu/adm/apply/international.html students with HKCEE and HKALE qualifications wishing to enter your University must reach? Are there any other tests that No. students with HKCEE and HKALE qualifications wishing to enter your University must take? When must they be taken? Is there an entry quota that No. applies to students with HKCEE and HKALE qualifications wishing to enter your University? Where can information be Up-to-date information can be found -

US Presidents

US Presidents Welcome, students! George Washington “The Father of the Country” 1st President of the US. April 30,1789- March 3, 1797 Born: February 22, 1732 Died: December 14, 1799 Father: Augustine Washington Mother: Mary Ball Washington Married: Martha Dandridge Custis Children: John Parke Custis (adopted) & Martha Custis (adopted) Occupation: Planter, Soldier George Washington Interesting Facts Washington was the first President to appear on a postage stamp. Washington was one of two Presidents that signed the U.S. Constitution. Washington's inauguration speech was 183 words long and took 90 seconds to read. This was because of his false teeth. Thomas Jefferson “The Man of the People” 3rd president of the US. March 4, 1801 to March 3, 1809 Born: April 13, 1743 Died: July 4, 1826 Married: Martha Wayles Skelton Children: Martha (1772-1836); Jane (1774-75); Mary (1778-1804); Lucy (1780-81); Lucy (1782-85) Education: Graduated from College of William and Mary Occupation: Lawyer, planter Thomas Jefferson Interesting Facts Jefferson was the first President to shake hands instead of bow to people. Thomas Jefferson was the first President to have a grandchild born in the White House. Jefferson's library of approximately 6,000 books became the basis of the Library of Congress. His books were purchased from him for $23,950. Jefferson was the first president to be inaugurated in Washington, D.C. Abraham Lincoln “Honest Abe” 16th President of the US. March 4, 1861 to April 15, 1865 Born: February 12, 1809 Died: April 15, 1865, Married: Mary Todd (1818-1882) Children: Robert Todd Lincoln (1843-1926); Edward Baker Lincoln (1846-50); William Wallace Lincoln (1850-62); Thomas "Tad" Lincoln (1853-71) Occupation: Lawyer Abraham Lincoln Interesting Facts Lincoln was seeing the play "Our American Cousin" when he was shot. -

Bill Bolling Contemporary Virginia Politics

6/29/21 A DISCUSSION OF CONTEM PORARY VIRGINIA POLITICS —FROM BLUE TO RED AND BACK AGAIN” - THE RISE AND FALL OF THE GOP IN VIRGINIA 1 For the first 200 years of Virginia's existence, state politics was dominated by the Democratic Party ◦ From 1791-1970 there were: Decades Of ◦ 50 Democrats who served as Governor (including Democratic-Republicans) Democratic ◦ 9 Republicans who served as Governor Dominance (including Federalists and Whigs) ◦ During this same period: ◦ 35 Democrats represented Virginia in the United States Senate ◦ 3 Republicans represented Virginia in the United States Senate 2 1 6/29/21 ◦ Likewise, this first Republican majority in the Virginia General Democratic Assembly did not occur until Dominance – 1998. General ◦ Democrats had controlled the Assembly General Assembly every year before that time. 3 ◦ These were not your “modern” Democrats ◦ They were a very conservative group of Democrats in the southern tradition What Was A ◦ A great deal of their focus was on fiscal Democrat? conservativism – Pay As You Go ◦ They were also the ones who advocated for Jim Crow and Massive resistance up until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of in 1965 4 2 6/29/21 Byrd Democrats ◦ These were the followers of Senator Harry F. Byrd, a former Virginia Governor and U.S. Senator ◦ Senator Byrd’s “Byrd Machine” dominated and controlled Virginia politics for this entire period 5 ◦ Virginia didn‘t really become a competitive two-party state until Ơͥ ͣ ǝ, and the first real From Blue To competition emerged at the statewide level Red œ -

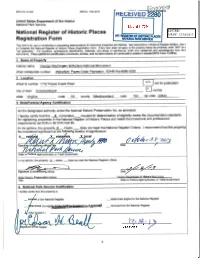

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV 0 ·~ 2013 National Register of Historic Places NAT. Re018TiR OF HISTORIC PlACES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name George Washington Birthplace National Monument other names/site number Wakefield. Popes Creek Plantation , VDHR File #096-0026 2. Location 1732 Popes Creek Road not for publication street & number L-----' city or town Colonial Beach ~ vicinity state Vir inia code VA county Westmoreland code _ _;_:19'--=-3- zip code -"'2=2:....;.4"""43.;;...._ ___ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _!__nomination_ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property .K._ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: x_ b state ' Ide "x n J.VIA.rVI In my opinion, the property .x..._ meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

In 193X, Constance Rourke's Book American Humor Was Reviewed In

OUR LIVELY ARTS: AMERICAN CULTURE AS THEATRICAL CULTURE, 1922-1931 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Schlueter, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Thomas Postlewait, Adviser Professor Lesley Ferris Adviser Associate Professor Alan Woods Graduate Program in Theatre Copyright by Jennifer Schlueter c. 2007 ABSTRACT In the first decades of the twentieth century, critics like H.L. Mencken and Van Wyck Brooks vociferously expounded a deep and profound disenchantment with American art and culture. At a time when American popular entertainments were expanding exponentially, and at a time when European high modernism was in full flower, American culture appeared to these critics to be at best a quagmire of philistinism and at worst an oxymoron. Today there is still general agreement that American arts “came of age” or “arrived” in the 1920s, thanks in part to this flogging criticism, but also because of the powerful influence of European modernism. Yet, this assessment was not, at the time, unanimous, and its conclusions should not, I argue, be taken as foregone. In this dissertation, I present crucial case studies of Constance Rourke (1885-1941) and Gilbert Seldes (1893-1970), two astute but understudied cultural critics who saw the same popular culture denigrated by Brooks or Mencken as vibrant evidence of exactly the modern American culture they were seeking. In their writings of the 1920s and 1930s, Rourke and Seldes argued that our “lively arts” (Seldes’ formulation) of performance—vaudeville, minstrelsy, burlesque, jazz, radio, and film—contained both the roots of our own unique culture as well as the seeds of a burgeoning modernism. -

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fred A

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-SIX This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archcological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents. GEORGE WASHINGTON BIRTHPLACE National Monument Virginia by J. Paul Hudson NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 26 Washington, D. C, 1956 The National Park System, of which George Washington Birthplace National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Qontents Page JOHN WASHINGTON 5 LAWRENCE WASHINGTON 6 AUGUSTINE WASHINGTON 10 Early Life 10 First Marriage 10 Purchase of Popes Creek Farm 12 Building the Birthplace Home 12 The Birthplace 12 Second Marriage 14 Virginia in 1732 14 GEORGE WASHINGTON 16 THE DISASTROUS FIRE 22 A CENTURY OF NEGLECT 23 THE SAVING OF WASHINGTON'S BIRTHPLACE 27 GUIDE TO THE AREA 33 HOW TO REACH THE MONUMENT 43 ABOUT YOUR VISIT 43 RELATED AREAS 44 ADMINISTRATION 44 SUGGESTED READINGS 44 George Washington, colonel of the Virginia militia at the age of 40. From a painting by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy, Washington and Lee University. IV GEORGE WASHINGTON "... His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives . -

2013 CNU Football Media Gui

2 2013 CHRISTOPHER NEWPORT UNIVERSITY FOOTBALL CNUSPORTS.COM NCAA playoffs 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012 table of contents Location .............................................................Newport News, Va. Department Phone ....................................................757-594-7025 Founded ................................................................................... 1961 Department Fax .........................................................757-594-7839 Enrollment .............................................................................. 5,000 Website........................................................... www.CNUsports.com Nickname ...........................................................................Captains Sr. Dir. Athletic Communications Colors .............................................................Royal Blue and Silver Francis Tommasino .....................................................757-594-7884 Conference .....................................................................USA South Director of Sports Information Stadium ..............................................................POMOCO Stadium Rob Silsbee .................................................................757-594-7382 President .......................................................Sen. Paul S. Trible, Jr. Asst. Director of Sports Information Director of Athletics .................................................... Todd Brooks Kenny Kline ................................................................757-594-7886