Moving Targets: Rethinking Anarchist Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue 2021 Welcome to the FREEDOM CATALOGUE

anarchist publishing Est. 1886 Catalogue 2021 wELCOME TO THE FREEDOM CATALOGUE Anarchism is almost certainly the most interesting political movement to have slipped under the radar of public discourse. It is rarely pulled up in today’s media as anything other than a curio or a threat. But over the course of 175 years since Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s declaration “I am an anarchist” this philosophy of direct action and free thought has repeatedly changed the world. From Nestor Makhno’s legendary war on both Whites and Reds in 1920s Ukraine, to the Spanish Civil War, to transformative ideals in the 1960s and street-fought antifascism in the 1980s, anarchism remains a vital part of any rounded understanding of humanity’s journey from past to present, let alone the possibilities for its future. For most of that time there has been Freedom Featuring books from Peter Kropotkin, Marie Press. Founded in 1886, brilliant thinkers past and Louise Berneri, William Blake, Errico Malatesta, Colin present have published through Freedom, allowing Ward and many more, this catalogue offers much us to present today a kaleidoscope of classic works of what you might need to understand a fascinating from across the modern age. creed. shop orders trade orders You can order online, by email, phone Trade orders come from Central Books, who or post (details below). Our business offer 33% stock discounts as standard. Postage hours are 10am-6pm, Monday to is free within the UK, with £2.50 extra for orders Saturday. from abroad — per order not per item. You can pay via Paypal on our website. -

Rebel Alliances

Rebel Alliances The means and ends 01 contemporary British anarchisms Benjamin Franks AK Pressand Dark Star 2006 Rebel Alliances The means and ends of contemporary British anarchisms Rebel Alliances ISBN: 1904859402 ISBN13: 9781904859406 The means amiemls 01 contemllOranr British anarchisms First published 2006 by: Benjamin Franks AK Press AK Press PO Box 12766 674-A 23rd Street Edinburgh Oakland Scotland CA 94612-1163 EH8 9YE www.akuk.com www.akpress.org [email protected] [email protected] Catalogue records for this book are available from the British Library and from the Library of Congress Design and layout by Euan Sutherland Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow To my parents, Susan and David Franks, with much love. Contents 2. Lenini8t Model of Class 165 3. Gorz and the Non-Class 172 4. The Processed World 175 Acknowledgements 8 5. Extension of Class: The social factory 177 6. Ethnicity, Gender and.sexuality 182 Introduction 10 7. Antagonisms and Solidarity 192 Chapter One: Histories of British Anarchism Chapter Four: Organisation Foreword 25 Introduction 196 1. Problems in Writing Anarchist Histories 26 1. Anti-Organisation 200 2. Origins 29 2. Formal Structures: Leninist organisation 212 3. The Heroic Period: A history of British anarchism up to 1914 30 3. Contemporary Anarchist Structures 219 4. Anarchism During the First World War, 1914 - 1918 45 4. Workplace Organisation 234 5. The Decline of Anarchism and the Rise of the 5. Community Organisation 247 Leninist Model, 1918 1936 46 6. Summation 258 6. Decay of Working Class Organisations: The Spani8h Civil War to the Hungarian Revolution, 1936 - 1956 49 Chapter Five: Anarchist Tactics Spring and Fall of the New Left, 7. -

Read Book Demanding the Impossible: a History of Anarchism

DEMANDING THE IMPOSSIBLE: A HISTORY OF ANARCHISM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Marshall | 818 pages | 01 Feb 2010 | PM Press | 9781604860641 | English | Oakland, United States Demanding the Impossible | The Anarchist Library Click here for one-page information sheet on this product. Cart Contents. Recent Posts. Price: 0. Add To Wishlist. Overview Tell a Friend. Send Message. Anarchism Books Combo Pack. A fantastic combo pack of anarchist philosophies, conversations, history and reference not to be missed! Peter Marshall Navigating the broad "river of anarchy," from Taoism to Situationism, from anarcho-syndicalists to anarcha-feminists, this volume is an authoritative and lively study of a widely misunderstood subject. What Is Anarchism? Donald Rooum This book is an introduction to the development of anarchist thought, useful not only to propagandists and proselytizers of anarchism but also to teachers and students, and to all who want to uncover the basic core of anarchism. Editors: Raymond Craib and Barry Maxwell A collection of essays on the questions of geographical and political peripheries in anarchist theory. Voices of the Paris Commune. Presenting a balanced and critical survey, the detailed document covers not only classic anarchist thinkers--such as Godwin, Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Reclus, and Emma Goldman--but also other libertarian figures, such as Nietzsche, Camus, Gandhi, Foucault, and Chomsky. Essential reading for anyone wishing to understand what anarchists stand for and what they have achieved, this fascinating account also includes an epilogue that examines the most recent developments, including postanarchism and anarcho-primitivism as well as the anarchist contributions to the peace, green, and global justice movements of the 21st century. -

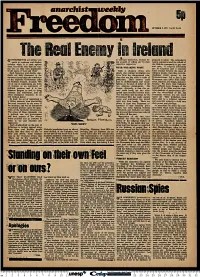

Standing on Their Own Feet Or on Ours?

anarchistmmweehly Vol 32 No 31 riOVERNMENTS are always very to extricate themselves, without be- prepared to admit. The campaign is quick to condemn and deplore ing accused of 'selling out' by their mainly centred around the refusal of ' violence when it is used against respective supporters. the Catholic community to pay rent them, but all the time they are wag- *2? and rates. If religious differences ing war on their own populations NEAR BREAKING POINT can be forgotten and a common in the name of 'Law and Order'. Such a situation shows \pry bond created between the mass of Such hypocrisy and double stan- clearly that nothing worthwhile can ordinary people, then this civil dis- dards are fully illustrated in the come from the compromised solu- obedience could spread to the statement issued after the conclusion tions that are the stock in trade of Protestant areas. Let us face it, the of the tripartite Government talks politicians. Their answers could Protestants also suffer from indig- on Northern Ireland. It reads: 'We lead to disillusionment and resent- nities, injustice, low wages, and poor are at one in condemning any form *SpV '■"■ t •■■■•.-•>a*-v.tv13fc:V-J~. ■ '. ¥r \£-\. ■':'<*.^^!.^/'Ui/^jKjp,-ki,f-^AJi^ fulness on the part of either of the . housing. We know that Catholics of violence as an instrument of il'*;(»»'>,i,^'lk"'f-l<*. -»fr''^ . Vt'/i'li'/-- 1 '' '*■ ■''■**4fflv- ■ ' V'^&f«Ufl*?tivr r two religious communities. The have suffered more because of the political pressure and it is our danger, obviously, is that this en- inability of the State and the capi- common purpose to seek to bring mity could break out into wide- talist methods of production to pro- violence and internment, and all spread open hostility between them. -

Everywhere from Britain’S Rebel Music Revival to Anti-Colonial Conflict in Papua, It’S Not All Paralysis and Defeat Around Here

XXXX 1 vol 79:2 winter 2019/20 anarchist journal by donation KICKING OFF EVERYWHERE FROM BRITain’S REBEL MUSIC REVIVAL TO ANTI-COLONIAL CONFLICT IN PAPUa, it’S NOT All PARALYSIS AND DEFEAT AROUND HERE Pic by Anzi Matta | pateron.com/anzimatta PLUS: M THE HOUSING CRISIS n RISE OF DOMESTIC MURDER aberdeen’S RADICAL SPACE @ BISEXUAL ACTIVISM IN LONDON 2 editorial It all just needs a spark. From Chile to and token giveaways, somehow manages some common denominator with us. Start Hong Kong, through Catalonia to France to contain it? Will it be the far-right with building structures based on the principle — it has been kicking off everywhere. their populist policies? Or will these of mutual aid: show how this can work in What these events have in common is that upheavals lead to long-lasting, positive practice. Share our knowledge of what they were all sparked by a government and revolutionary changes to the world the State is, and what its main principles decision, of lesser or greater significance, we all live in, the sort of changes we will are. Join in with local struggles. Show but in all cases the States which did so be happy to support? that anarchism, while it maintains a solid thought they could get away with it, as In the UK one may, perhaps reputation of utopianism, can be and is they have done for decades until now. optimistically, assume that with almost the answer to the world-wide problems These decisions have been inflicted on a decade of the Tory rule behind us that we are all facing. -

Changing Anarchism.Pdf

Changing anarchism Changing anarchism Anarchist theory and practice in a global age edited by Jonathan Purkis and James Bowen Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6694 8 hardback First published 2004 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset in Sabon with Gill Sans display by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by CPI, Bath Dedicated to the memory of John Moore, who died suddenly while this book was in production. His lively, innovative and pioneering contributions to anarchist theory and practice will be greatly missed. -

Akboekencatalogus.Pdf

1. An anarchist FAQ (vol1) -Lian Mckay (20 euro) 2. The voltairine De Cleyre reader—AJ. Brigati (15 euro) 3. Obsolete communism. The left wing alternative—Daniel Cohn, Gabriel Bendit (19,50 euro) 4. The struggle against the state and other essays—Nestor Makhno (12 euro) 5. The friends of Durruti group 1937-1939—Augustin Guillamon (12 euro) 6. Radical priorities —Noam Chomsky (13 euro) 7. The Russian anarchists—Paul Avrich (14,50 euro) 8. Unfinished business —the politics of Class War (6 euro) 9. Abolition now, ten years of strategy and struggle against the prison complex—CR10 Collective (12euro) 10. What is anarchism? - Alexander Berkman (15 euro) 11. The Spanish anarchists, the heroic years 1868-1936—Murray Bookchin (21 euro) 12. Italian anarchism 1864-1892—Munzig Pernicone (20 euro) 13. Workers councils—Anton Pannekoek (12 euro) 14. Vision on Fire—Emma Goldman on the Spanish revolution (19,50 euro) 15. Facing the enemy—A. Skirda (18 euro) 16. Nowtopia—Chris Carlsson (15 euro) 17. Partisans, Women in the armed resistance to fascism and German occupation 1936– 1945—Ingrid Strobl (13 euro) 18. Critical Mass, bicycling’s defiant celebration—Chris Carisson (18 euro) 19. Nestor Makhno, anarchy’s cossack—Alexander Skirda (19 euro) 20. Dreams of freedom, a Ricardo Flores Magon reader— Chaz Bufe and Mitchell Cowen Verter (15 euro) 21. Pacifism as pathology, reflections on the role of armed struggle in North America—Ward Churchill, Mike Ryan (9;60 euro) 22. For workers power, the selected writings of Maurice Brinton—David Goodway (18euro) 23. Social ecology and communalism—Murray Bookchin (10,50 euro) 24. -

Anarchism As a Culture?

Anarchism as a Culture? Kljajić, Ivana Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Rijeci, Filozofski fakultet u Rijeci Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:186:222392 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-03 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - FHSSRI Repository Sveučilište u Rijeci Filozofski fakultet u Rijeci Odsjek za kulturalne studije Ivana Kljajić Anarchism as a Culture? Rijeka, 23. rujna 2016. Ivana Kljajić: Anarchism as a Culture? Sveučilište u Rijeci Filozofski fakultet u Rijeci Odsjek za kulturalne studije Ivana Kljajić Anarchism as a Culture? Mentorica: dr.sc. Sarah Czerny Rijeka, 23. rujna 2016. 1 Ivana Kljajić: Anarchism as a Culture? Table of Contents: ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………… INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………….. 1. ANARCHISM…………………………………………………………………………… 1.1.What Is Anarchism?...................................................................................................... 1.2.The Enlightenment and Liberalism as Great Influences on the Emergence of the Anarchist Movement…………………………………………………… 1.3.Origins of the Anarchist Movement…………………………………………............... 1.4.Anarchism and the Concepts of Freedom and Equality………………………………. 1.5.Anarchism and Democracy……………………………………………………………. 1.6.Anarchism and Its Relationship with -

Catalogue 2018

anarchist publishing Est. 1886 Catalogue 2018 INTRO/INDEX wELCOME TO THE FREEDOM CATALOGUE Anarchism is almost certainly the most interesting political movement to have slipped under the radar of public discourse. It is rarely pulled up in today’s media as anything other than a curio or a threat. But over the course of 175 years since Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s declaration “I am an anarchist” this philosophy of direct action and free thought has repeatedly changed the world. From Nestor Makhno’s legendary war on both Whites and Reds in 1920s Ukraine, to the Spanish Civil War, to transformative ideals in the 1960s and street-fought antifascism in the 1980s, anarchism remains a vital part of any rounded understanding of humanity’s journey from past to present, let alone the possibilities for its future. For most of that time there has been Freedom Press. Founded in 1886, brilliant thinkers past and present have published through Freedom, allowing us to present today a kaleidoscope of classic works from across the modern age. Featuring books from Peter Kropotkin, Nicolas Walter, William Blake, Errico Malatesta, Colin Ward and many more, this catalogue offers much of what you might need to understand a fascinating creed. ordering direct trade You can order online, by email, phone Trade orders come from Central Books, or post (details below). Our business who offer 33% stock discounts as hours are 10am-6pm, Monday to standard. Saturday. Postage is free within the UK, with You can pay via Paypal on our £2.50 extra for orders from abroad — website. -

Ria Us a T Q .Com Mn

buchantiquariat Internet: http://comenius-antiquariat.com 2448 • Albrecht/ Lock/ Wulf. Arbeitsplätze durch Rüstung. Warnung vor falschen Hoffnungen. rororo Datenbank: http://buch.ac 4266, 1978. 237 S. CHF 10 / EUR 6.60 A Q Wochenlisten: http://buchantiquariat.com/woche/ Kataloge: http://antiquariatskatalog.com 102541 • Allen, Durward L. u.a., Natur erleben, Natur verstehen. Stuttgart u.a.: Das Beste, 1979. 335 A RI AGB: http://comenius-antiquariat.com/AGB.php Seiten mit Register. Halbkunstleder. 4to. CHF 35 / EUR 23.10 • Originaltitel: Joy of nature; deutsch von .COM M N US ! com Karl Wilhelm Harde. T 78063 • Alley, Rewi, Quer durch China. Reisen in die Kulturrevolution 1966 - 1971. Stuttgart: Verlag Neuer Weg 1977. 502 S. mit Abbildungen. kart. CHF 22 / EUR 14.52 11923 • Almanach Socialiste 1925. Quatrième année. La Chaux-de-Fonds: Imprimerie coopérative 1925. 96 S. brosch. CHF 21 / EUR 13.86 Katalog Soziale Bewegungen 104803 • Alt, Franz, Frieden ist möglich. Die Politik der Bergpredigt. 23. Auflage, 840. - 870. Tausend. München, Zürich: Piper, 1986. 119 Seiten mit Literaturverzeichnis. Kartoniert. CHF 10 / EUR 6.60 • COMENIUS-ANTIQUARIAT • Staatsstrasse 31 • CH-3652 Hilterfingen Serie Piper; 284: Aktuell. Fax 033 243 01 68 • E-Mail: [email protected] 112301 • Altermatt, Urs und Hanspeter Kriesi [Hrsg.], Rechtsextremismus in der Schweiz. Einzeltitel im Internet abrufen: http://buch.ac/?Titel=[Best.Nr.] Stand: 14/03/2010 • 2692 Titel Organisationen und Radikalisierung in den 1980er und 1990er Jahren. Zürich: Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 1995. 264 Seiten mit Literaturverzeichnis. Kartoniert. CHF 25 / EUR 16.50 • Vorwort von Arnold Koller. - Rücken ben leicht bestossen. 78830 • Abendroth, Wolfgang, Sozialgeschichte der europäischen Arbeiterbewegung. -

Black Flag Supplement

-I U The oodcock - Sansom School of Fals|f|cat|o (Under review: the new revised edition of Geo. Woodcock’s no mnnection with this George Spanish). The book wrote the Anarchists off ‘Anarchism’, published by Penguin books; the Centenary Edition Woodcock! Wrote all essay 111 3 trade altogether. The movement was dead. of ‘Freedom’, published by Freedom Press.) ‘figiggmfii“,:§°:i;mfit‘3’§ar’§‘,ia’m,‘§f“;L3;S, He was its ‘obituarist’. Now he has fulsome praise of his ‘customary issued a revised version of the book brilliance (he had only written one brought up ‘to date’. He wasn’t HEALTH WARNING; Responses to preparing for a three volume history °i3iiei' Pieee) and ’iiiei5iVe insight’ " it wrong, he says, it did die — but his (‘I find the influence of Stirner on was a Pavlovian response from his book brought it back to life again! Freedom Press clique have been namesake’s coterie. It explains what It adds a history’ of the British described by our friends as ‘terminally British anarchism very interesting. .’) The Amsterdam Institute for Social this George Woodcock set out movement for his self-glorification, boring’ but can we let everything History, funded by the Dutch govem- steadily to build up. actually referring to the British pass? We suggest using this as a ment, now utilises the CNT archives He came on the anarchist scene delegate to the Carrara conference supplement to either ‘Anarchism’ or to establish itself (to quote Rudolf de during the war, profiteering on the denouncing those who pretended to ‘Freedom Centennial’, especially when Jong) as ‘paterfamilias’ between the boom in anarchism to get into the be anarchists but were so in name you feel tired of living. -

Ethical Record the Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol

Ethical Record The Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol. 113 No. 4 £1.50 April 2008 S. Root', Donald Rooum's Wildcat (see page 8) BLASPHEMY REPEAL — IS THIS THE END? David Nash 3 UN VOTE MARKS THE END OF UNIVERSAL HUMAN RIGHTS 7 VIEWPOINT - HOW HITLER FAVOURED CHRISTIANITY Doncdd Roount 8 DONALD ROOUM,CARTOONS SINCE 1980 8 PERSUED BY DEMONS - A RATIONAL APPROACH TO THE DRINK PROBLEM Terry Liddle MENTAL ROUGHAGE FOR CONSIDERATION Albert Adler 13 THE FREE WILL DEBATE CONTINUES A Reply to Chris Broacher Tom Rubens 14 ON BEING JEWISH Isaac Ascher 19 ETHICAL SOCIETY EVENTS 24 SOUTH PLACE ETHICAL SOCIETY Conway Hall Humanist Centre 25 Red Lion Square, London WC I R 4RL. Tel: 020 7242 8034 Fax: 020 7242 8036 Websne: www.ethicalsoc.org.uk email: [email protected] Chairman: Giles Enders Hon. Rep.: Don Liversedge Vice-chairman: Terry Mullins Treasurer: John Edwards Registrar: Donald Rooum Editor: Norman Bacrac SPES Staff Executive Officer: Emma J. Stanford Tel: 020 7242 8034 Finance Officer: Linda Alia Tel: 020 7242 8034 Lettings Officer: Carina Dvorak Tel: 020 7242 8032 librarian/Programme Coordinator: Jennifer leynes M.Sc. Tel: 020 7242 8037 Lettings Assistant: Marie Aubrechtova Caretakers: Eva Aubrechtova (i/c); Tel: 020 7242 8033 together with: Shaip Bullaku, Angelo Edrozo, Nikola Ivanovski, Alfredo Olivio, Rogerio Retuerna. David Wright Maintenance Operative: Zia Hameed New Member We welcome to the Society Mike Ward of Farnham Humanists Obituary AL (Lawrence) Payne (1911-2008) Member A .L. Payne has died. His widow Nan tells us that Lawrence was always interested in ethical issues.