Publishing Camp: Queering Dissemination Gallery Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Show Notes At

CHVRCHES FAN PODCAST - #027 SHOW NOTES Official site: www.chvrch.es Shop: www.chvrchesshop.com , chvrchesus.shopfirebrand.com (US), chvrches.firebrandstores.com (UK) Contact the podcast : @chvrchespodcast, TWITTER : @chvrches, @Iain_A_Cook, @doksan, @laurenevemay, www.chvrchespodcast.com , [email protected] Record Label : @goodbye_records; goodbyerecords.com 619-631-4433 More info: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chvrches Fans : @chvrchesfans, @LaurenMayberryF, @ChvrchesIsLife, @CHVRCHESSQVAD, www.reddit.com/r/chvrches/ , ANNOUNCEMENT BAND INTRO + #27 for November 11, 2017 INTRODUCTION SONG - CHVRCHES - “Keep Me On Your Side” ● https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Every_Open_Eye ● https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jzGJWq-owH4 ● https://genius.com/Chvrches-keep-you-on-my-side-lyrics Welcome to the 27th CHVRCHES Fan Podcast recorded on November 11, 2017. My name is Steve Holden and I am recording this podcast in Southern California near San Diego. Nov. 11 is Veterans Day in the United States. If you served then thank you for your service. That intro song sample was Keep Me On Your Side from CHVRCHES 2nd Album Every Open Eye. It is the 3rd song on that album and I really liked the [Verse 3] ● Everyone comes, but only I stay ● Nowhere to look, nowhere to turn to fall away ● What if I should call it off? ● Hold up my demands with my heart uncrossed The standard version of the album Every Open Eye had 11 songs with 5 official singles Leave A Trace, Never Ending Circles, Clearest Blue, Empty Threat, and Bury It and one could argue that now “Down Side Of Me” should be consider a single with the recently released live version. -

Woman As a Category / New Woman Hybridity

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 1 (2018) The Affective Aesthetics of Transnational Feminism Silvia Schultermandl, Katharina Gerund, and Anja Mrak ABSTRACT: This review essay offers a consideration of affect and aesthetics in transnational feminism writing. We first discuss the general marginalization of aesthetics in selected canonical texts of transnational feminist theory, seen mostly as the exclusion of texts that do not adhere to the established tenets of academic writing, as well as the lack of interest in the closer examination of the features of transnational feminist aesthetic and its political dimensions. In proposing a more comprehensive alternative, we draw on the current “re-turn towards aesthetics” and especially on Rita Felski’s work in this context. This approach works against a “hermeneutics of suspicion” in literary analyses and re-directs scholarly attention from the hidden messages and political contexts of a literary work to its aesthetic qualities and distinctly literary properties. While proponents of these movements are not necessarily interested in the political potential of their theories, scholars in transnational feminism like Samantha Pinto have shown the congruency of aesthetic and political interests in the study of literary texts. Extending Felski’s and Pinto’s respective projects into an approach to literary aesthetics more oriented toward transnational feminism on the one hand and less exclusively interested in formalist experimentation on the other, we propose the concept of affective aesthetics. It productively complicates recent theories of literary aesthetics and makes them applicable to a diverse range of texts. We exemplarily consider the affective dimensions of aesthetic strategies in works by Christina Sharpe, Sara Ahmed, bell hooks, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who promote the idea of feminism as an everyday practice through aesthetically rendered texts that foster a personal and intimate link between the writer, text, and the reader. -

Phenomenology+Of+Whiteness.Pdf

Feminist Theory http://fty.sagepub.com/ A phenomenology of whiteness Sara Ahmed Feminist Theory 2007 8: 149 DOI: 10.1177/1464700107078139 The online version of this article can be found at: http://fty.sagepub.com/content/8/2/149 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Feminist Theory can be found at: Email Alerts: http://fty.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://fty.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://fty.sagepub.com/content/8/2/149.refs.html Downloaded from fty.sagepub.com at Royal Institute of Technology on September 19, 2011 149 A phenomenology of whiteness FT Feminist Theory Copyright © 2007 SAGE Publications (London, Los Angeles, New Delhi, and Singapore) vol. 8(2): 149–168. 1464–7001 DOI: 10.1177/1464700107078139 Sara Ahmed Goldsmiths College, University of London http://fty.sagepub.com Abstract The paper suggests that we can usefully approach whiteness through the lens of phenomenology. Whiteness could be described as an ongoing and unfinished history, which orientates bodies in specific directions, affecting how they ‘take up’ space, and what they ‘can do’. The paper considers how whiteness functions as a habit, even a bad habit, which becomes a background to social action. The paper draws on experiences of inhabiting a white world as a non-white body, and explores how whiteness becomes worldly through the noticeability of the arrival of some bodies more than others. A phenomenology of whiteness helps us to notice institutional habits; it brings what is behind to the surface in a certain way. -

Home and Away, Sara Ahmed

A Never Ending Journey: The Impossibilities of Home in Sirena Selena vestida de pena and Flores de otro mundo. Irune del Rio Gabiola Butler University What is home? The place I was born? Where I grew up? Where my parents live? Where I live and work as an adult? Is home a geographical space, a historical space, and emotional, sensory space? Feminism Without Borders, Chandra Mohanty Reconsiderations of home have been crucially examined in Caribbean cultural productions. As Jamil Khader argues in her article on “Subaltern Cosmopolitanism: Community and Transnational Mobility in Caribbean Postcolonial Feminist Writings,” Caribbean feminists are faced with the task of challenging a conventional idea of home that has historically located women and other marginal subjects under conditions of oppression and exploitation. In focusing on the narratives by Aurora Levins Morales, Rosario Morales and Esmeralda Santiago, she points out the infinite sense of homelessness that invades, in particular, these Puerto Rican individuals who need to find more productive manners to articulate “home” while establishing a crucial critique of its traditional significance. Despite the postcolonial approach unfolded by Khader and by those Caribbean feminist scholars, the contemporary works I analyze in this article show a complex dialogue and juxtaposition between a desire for traditional home and the above mentioned sense of homelessness inherent to Caribbean marginal subjects. Exploring the ambitious itineraries of Sirena in Sirena Selena vestida de pena (200) and Milady in the film Flores de otro mundo (1999), I emphasize the permanent dichotomy that exists when social outcasts face home, migration and forced displacement. The resolution to a sense of homelessness does not always entail the path of providing “subaltern cosmopolitanisms” stressing “international linkages and hemispheric connections” (Khader 73), but they are rather determined to eternal uncomfortable itineraries at the time that they long for a nostalgic prelapsarian idea of home. -

Reading List 1: Feminist Theories/ Interdisciplinary Methods Chair: Liz Montegary I Am Interested in the Ways in Which Political

Reading List 1: Feminist theories/ Interdisciplinary methods Chair: Liz Montegary I am interested in the ways in which political and social categories get constructed through, and onto, the body. And in turn, the way bodies themselves are not fixed or given, but are constantly shaped and altered through material and political means. Biopower is central to this inquiry, as is feminist theories of gender, sex, race, and dis/ability. To me, this is both material and discursive, and I honestly question the distinction between the two. For this list, I am thinking through ways in which bodies get inscribed with meaning, measured, and surveyed, as well as the ways in which they are literally shaped by these same institutions which discipline, order, and attempt to optimize them. The idea of what is to be desired or “optimized” in a body is particularly important in thinking about sports - by that I mean that the ways in which disciplining the body is also about trying to enhance it. Biopower and Bodies Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality Volume I, 1978 Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeus Viscus, 2014 Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, 1990 Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex,’ 1993 Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism, 1994 Dean Spade, Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics and the Limits of Law, 2011 Dorothy Roberts, Fatal Invention **Jasbir Puar, Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability, 2017 Jasbir Puar, Terrorist Assemblages, 2007 Eugenics History Jennifer Terry, An American Obsession Julian Carter, The Heart of Whiteness Stein, Melissa N. Measuring Manhood: Race and the Science of Masculinity, 1830–1934, 2015 Snorton, C. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Name: Sara Ahmed Appointments

Curriculum Vitae Name: Sara Ahmed Appointments: 2005-2016 Professor of Race and Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London 2004-2005 Reader in Race and Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London 2002 -2004 Reader in Women's Studies, Lancaster University 2001-2002 Senior Lecturer in Women’s Studies, Lancaster University 1994-2001 Lecturer in Women's Studies, Lancaster University. Qualifications: 1991- 1994 PhD, Centre for Critical and Cultural Theory, Cardiff University (awarded 1995) 1989-1990 B.A.(hons) in English, University of Adelaide. (First Class) 1987-1989 BA. University of Adelaide (English, Philosophy and History) Senior positions: 2013-2016 Director of the Centre for Feminist Research, Goldsmiths, University of London 2002-2003 Director of Women's Studies, Lancaster University 2000-2002 Co-Director of Women’s Studies, Lancaster University 1998-1999 Acting Director of Women's Studies, Lancaster University Visiting Appointments: Diane Middlebrook and Carl Djerassi Visiting Professor in Gender Research, Cambridge University, Spring term 2013 Laurie New Jersey Chair in Women’s Studies, Rutgers University, Spring Semester 2009. 1 Visiting Research Fellow, Department of Gender Studies, University of Sydney (November 2003- August 2004) Visiting Research Fellow, Department of Social Inquiry, University of Adelaide (August -December 1999) Prizes: Feminist and Women’s Studies Network (FWSA) Book Prize 2012, The Promise of Happiness for ‘ingenuity and scholarship in the fields of feminism, gender or women’s studies.’ Phenomenology Roundtable Award 2010 for ‘outstanding contribution to the field of phenomenological research.’ Publications: Single-Authored Books (2017). Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press. Translated into Swedish 2017. (2014) The Cultural Politics of Emotion. -

Living a Feminist Lifesara Ahmed

“Everyone should read this book.” —bell hooks Living a Feminist Life Sara ahmed SARA AHMED Living a Feminist Life Duke University Press / Durham and London / 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Ahmed, Sara, [date] author. Title: Living a feminist life / Sara Ahmed. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016032264 (print) lccn 2016033775 (ebook) isbn 9780822363040 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822363194 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373377 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: Feminist theory. | Feminism. Classification: lcc hq1190.a36 2017 (print) | lcc hq1190 (ebook) | ddc 305.4201—dc23 lc record available at https: // lccn .loc .gov / 2016032264 Cover Art: Carrie Moyer, Chromafesto (Sister Resister 1.2), 2003, acrylic, glitter on canvas, 36 × 24 inches. © Carrie Moyer. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York. To the many feminist killjoys out there doing your thing: THIS ONE IS FOR YOU. CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction Bringing Feminist Theory Home 19 PART I BECOMING FEMINIST 21 1. Feminism Is Sensational 43 2. On Being Directed 65 3. Willfulness and Feminist Subjectivity 89 PART II DIVERSITY WORK 93 4. Trying to Transform 115 5. Being in Question 135 6. Brick Walls 161 PART III LIVING THE CONSEQUENCES 163 7. Fragile Connections 187 8. Feminist Snap 213 9. Lesbian Feminism 235 Conclusion 1 A Killjoy Survival Kit 251 Conclusion 2 A Killjoy Manifesto 269 Notes 281 References 291 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is the first time I have written a book alongside a blog. -

The Life and Work of Gloria Anzaldúa: an Intellectual Biography

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2012 THE LIFE AND WORK OF GLORIA ANZALDÚA: AN INTELLECTUAL BIOGRAPHY Elizabeth Anne Dahms University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dahms, Elizabeth Anne, "THE LIFE AND WORK OF GLORIA ANZALDÚA: AN INTELLECTUAL BIOGRAPHY" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 6. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/6 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

Performing Citizenship Bodies, Agencies, Limitations

PERFORMING CITIZENSHIP BODIES, AGENCIES, LIMITATIONS EDITED BY Paula Hildebrandt, Kerstin Evert, Sibylle Peters, Mirjam Schaub, Kathrin Wildner AND Gesa Ziemer Performance Philosophy Series Editors Laura Cull Ó Maoilearca University of Surrey Guildford, UK Alice Lagaay Hamburg University of Applied Sciences Hamburg, Germany Will Daddario Independent Scholar Asheville, NC, USA Performance Philosophy is an interdisciplinary and international field of thought, creative practice and scholarship. The Performance Philosophy book series comprises monographs and essay collections addressing the relationship between performance and philosophy within a broad range of philosophical traditions and performance practices, including drama, the- atre, performance arts, dance, art and music. It also includes studies of the performative aspects of life and, indeed, philosophy itself. As such, the series addresses the philosophy of performance as well as performance-as- philosophy and philosophy-as-performance. Series Advisory Board: Emmanuel Alloa, Assistant Professor in Philosophy, University of St. Gallen, Switzerland Lydia Goehr, Professor of Philosophy, Columbia University, USA James R. Hamilton, Professor of Philosophy, Kansas State University, USA Bojana Kunst, Professor of Choreography and Performance, Institute for Applied Theatre Studies, Justus-Liebig University Giessen, Germany Nikolaus Müller-Schöll, Professor of Theatre Studies, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Martin Puchner, Professor of Drama and of English and Comparative -

Student Activities Fee Reconsidered New Act for Univ. Theatre Department

IInside: Looking '~ntothe· Future\ Today's weather:' A five star All-American NON PROFIT ORG Mostly sunny neW8paper . US POSTAGE high in the 40s' PAID I Newark Del Permll No 26 Vol. 114 No. 13 Student Center, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware 19716 Friday, March 4, 1988 Student activities fee reconsidered by Kean Burenga see editorial, p.8 Administrative News Editor who should be charged. President Russel C. Jones "We have to find an ap and Staurt Sharkey, vice propriate mechanism for im president for student affairs, plementing the fee and mak are designing a proposal for a ing it work," he commented. comprehensive student act Jones and Sharkey will sub vities fee at the university, the mit the final proposal to the president said. Student Mfairs Committee of Although details are still be the board of trustees later this ing worked out, Sharkey ex spring. plained, funds generated from If the committee approves the proposed fee would pro the proposition it will then go vide more money for clubs and before the full board for ap organizations and allow enter proval at their semi-annual tainment programming to be meeting in May. This will represent the third student organizations received expanded. time in eight years that an ac Jones ~dded that another $172,830 from the university in area where the fee might be tivities fee has been proposed the current academic year. used is in expanding in to the university's administra The student organizations -tramural sports at the tion. The fee was rejected the originally requested university. -

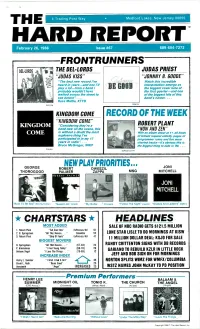

Frontrunners Headlines

THE 4 Trading Post Way Medford Lakes. New Jersey 08055 HARD REPORT February 26, 1988 Issue #67 609-654-7272 alb FRONTRUNNERS THE DEL -LORDS JUDAS PRIEST "JUDAS KISS" "JOHNNY B. GOODE" "The best new record I've Watch this incredible heard in years-and one interpretation emerge as play a lot-from a band / the biggest cover tune of probably wouldn't have the first quarter-and one walked across the street to of the biggest hits of this see before".. band's career. ... Russ Mottla, KTYD Atlantic Enigma KINGDOM COME RECORD OF THE WEEK "KINGDOM COME" ROBERT PLANT KINGDOM "Considering they're a band new on the scene, this "NOW AND ZEN" COME is without a doubt the most With an a/bum debut at 1*, all kinds explosive thing I've of instant request activity, pages of participated in in my 17 programmer raves and five more years in radio". ... ofiej4v.charted tracks-it's obvious this is Bruce McGregor, WRIF the biggest thing to date in '88.... Polydor E s Pa r a nz a / At I NEW PLAY PRIORITIES... JONI GEORGE ROBERT DWEEZIL THOROGOOD PALMER ZAPPA MSG MITCHELL ERT PALMER MOOG JONI MITCHELL "Born To Be Bad" (EMI/Manhattan) "Sweet Lies" (Island) ' My Guitar (Chrysalis) 'Follow The Night" (capitol)"Snakes And Ladders" (Geffen) CHARTSTARS HEADLINES MOST ADDED SALE OF NBC RADIO GETS $121.5 MILLION 1. Robert Plant "Tall Cool One" EsParanza/Atl 91 LONE STAR LISLE TO DO MORNINGS AT KISW 2. B. Springsteen "All That Heaven . ." Columbia 52 3. Robert Plant "Ship Of Fools" EsParanza/Atl 47 11 MILLION DOLLAR DEAL: KSJO FOR SALE BIGGEST MOVERS RANDY CRITTENTON SIGNS WITH DB RECORDS B. -

REAL ARAOKE® Designed & Built in Melbourne, Australia

® REAL ARAOKE® Designed & Built In Melbourne, Australia Song Book December 2017 By ARTIST ® Track List By ARTIST REAL ARAOKE CONTENTS 2x Speakers / 1x Mixer 2x Microphones 1x Display / 1x Karaoke Box 1x iPad 2x Speaker Stands 2x Song Books 2x Speaker Leads 1x Music Lead 2x Microphone Leads 1x Power Lead 1x Power Board 1x Power Extension Lead SETUP INSTRUCTIONS IMPORTANT After powering on the system, wait for the WiFi symbol to appear on the top left of the iPad: In the REAL KARAOKE app touch the AirPlay button and select REAL KARAOKE: Page 2/167 Connect With Us On ® REAL ARAOKE Track List By ARTIST CONTENTS 1 112 PEACHES & CREAM 2 911 MORE THAN A WOMAN 3 1927 IF I COULD 4 1927 THATS WHEN I THINK OF YOU 5 10000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 6 10000 MANIACS LIKE THE WEATHER 7 10000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS 8 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2x Speakers / 1x Mixer 2x Microphones 1x Display / 1x Karaoke Box 1x iPad 2x Speaker Stands 2x Song Books 9 10CC IM NOT IN LOVE 10 10CC RUBBER BULLETS 11 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 12 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT 13 3 DOORS DOWN HERE BY ME 14 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 15 3 DOORS DOWN ITS NOT MY TIME 16 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 2x Speaker Leads 1x Music Lead 2x Microphone Leads 1x Power Lead 1x Power Board 1x Power Extension Lead 17 30 SECONDS TO MARS CLOSER TO THE EDGE 18 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 19 3OH3 DONT TRUST ME SETUP INSTRUCTIONS 20 3OH3 YOURE GONNA LOVE THIS 21 3OH3 FEATURING KATY PERRY STARSTRUKK 22 3OH3 FEATURING KESHA MY FIRST KISS 23 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 24 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 25 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER