Probing the Unnatural*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orthographic Characterization of Rendaku and Lyman's

a journal of Kawahara, Shigeto. 2018. Phonology and orthography: The orthographic general linguistics Glossa characterization of rendaku and Lyman’s Law. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 3(1): 10. 1–24, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.368 RESEARCH Phonology and orthography: The orthographic characterization of rendaku and Lyman’s Law Shigeto Kawahara The Keio Institute of Cultural and Linguistic Studies, Keio University, 2-15-45 Minato-ku, Mita, Tokyo, JP [email protected] This paper argues that phonology and orthography go in tandem with each other to shape our phonological behavior. More concretely, phonological operations are non-trivially affected by orthography, and phonological constraints can refer to them. The specific case study comes from a morphophonological alternation in Japanese, rendaku. Rendaku is a process by which the first consonant of the second member of a compound becomes voiced (e.g., /oo/ + /tako/ → [oo+dako] ‘big octopus’). Lyman’s Law blocks rendaku when the second member already contains a voiced obstruent (/oo/ + /tokage/ → *[oo+dokage], [oo+tokage] ‘big lizard’). Lyman’s Law, as a constraint which prohibits a morpheme with two voiced obstruents, is also known to trigger devoicing of geminates in loanwords (e.g. /beddo/ → [betto] ‘bed’). Rendaku and Lyman’s Law have been extensively studied in the past phonological literature. Inspired by recent work that shows the interplay between orthographic factors and grammatical factors in shaping our phonological behaviors, this paper proposes that rendaku and Lyman’s Law actually operate on Japanese orthography. Rendaku is a process that assigns dakuten diacritics, and Lyman’s Law prohibits morphemes with two diacritics. -

Contrastive Feature Typologies of Arabic Consonant Reflexes

languages Article Contrastive Feature Typologies of Arabic Consonant Reflexes Islam Youssef Department of Languages and Literature Studies, University of South-Eastern Norway, 3833 Bø i Telemark, Norway; [email protected] Abstract: Attempts to classify spoken Arabic dialects based on distinct reflexes of consonant phonemes are known to employ a mixture of parameters, which often conflate linguistic and non- linguistic facts. This article advances an alternative, theory-informed perspective of segmental typology, one that takes phonological properties as the object of investigation. Under this approach, various classificatory systems are legitimate; and I utilize a typological scheme within the framework of feature geometry. A minimalist model designed to account for segment-internal representations produces neat typologies of the Arabic consonants that vary across dialects, namely qaf,¯ gˇ¯ım, kaf,¯ d. ad,¯ the interdentals, the rhotic, and the pharyngeals. Cognates for each of these are analyzed in a typology based on a few monovalent contrastive features. A key benefit of the proposed typologies is that the featural compositions of the various cognates give grounds for their behavior, in terms of contrasts and phonological activity, and potentially in diachronic processes as well. At a more general level, property-based typology is a promising line of research that helps us understand and categorize purely linguistic facts across languages or language varieties. Keywords: phonological typology; feature geometry; contrastivity; Arabic dialects; consonant reflexes Citation: Youssef, Islam. 2021. Contrastive Feature Typologies of 1. Introduction Arabic Consonant Reflexes. Languages Modern Arabic vernaculars have relatively large, but varying, consonant inventories. 6: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ Because of that, they have been typologized according to differences in the reflexes of their languages6030141 consonant phonemes—differences which suggest common origins or long-term contact (Watson 2011a, p. -

Rendaku As a Rhythmic Stabilizer in Eastern Old Japanese Poetry John

Rendaku as a rhythmic stabilizer in Eastern Old Japanese poetry John Kupchik Kyoto University / JSPS The Eastern Old Japanese dialects, spoken in the 8th century and attested in books 14 and 20 of the Man’yōshū poetry anthology, are a heterogeneous group of related language varieties that each display some of the earliest attested examples of rendaku. Morpheme-based rendaku, which manifests when a phonologically reduced, nasal-initial copula, case suffix, or final syllable of a nominal root fuses with a following voiceless onset, is the most commonly attested type. In fact, it may even occur twice in the same line. An example is given in (1) below. (1) M20:4368.1-2 (Pitati province) 久自我波々 / 佐氣久阿利麻弖 kunzi-ŋ-gapa pa / sake-ku ari-mat-e PN-GEN-river TOP / be.safe-AVINF ITER-wait-IMP ‘Be waiting for me safely, at Kunzi river!’ The underlying form in the first line of (1) is /kunzi-nə kapa pa/. Examples of process-based rendaku are also attested, in which case no segmentable morpheme can be derived from the resulting voiced onset. This type of rendaku is only attested a few times, and only in reduplicated forms. It has a function of pluralization, which is not found in morpheme-based rendaku. An example is shown in (2) below. (2) M20:4391.1-3 (Simotupusa province) 久尓具尓乃 / 夜之里乃加美尓 / 奴作麻都理 kuni- ŋguni-nə / yasiri-nə kami-ni / nusa matur-i province-REDUP-GEN / shrine-GEN deity-DAT / paper_offering offer-INF ‘I make paper offerings to the deities in the shrines of many provinces.’ This talk will focus on the use of morpheme-based rendaku to maintain rhythmic stability in poetic verse. -

Rendaku in Japanese Place Names, by Focusing on Morphemes of Which It Is Known That They Have a Tendency to Undergo Rendaku, but Not Always

Rendaku in Japanese place names Michelle Hermina van Bokhorst 1348884 MA East Asian Studies Leiden University MA thesis 1 July 2018 Dr. W. Uegaki 13113 words Content 1. Introduction 3 2. Division within Japanese dialects 3 3. Rendaku in common nouns 6 3.1 General overview 6 3.2 Dialectal variation 8 4. Rendaku in names 9 4.1 Accents and morphemes 9 4.2 Individual segments 11 4.3 Diachronic variation 12 4.4 Synchronic variation 13 5. Research questions and hypotheses 16 5.1 Rendaku according to a core periphery model 16 5.2 Morphemes and rendaku sensitivity 18 6. Method 19 7. Results 22 7.1 Influence of the region 22 7.2 Influence of morphemes 24 7.3 Names ending with kawa 26 7.4 Names ending with saki 27 7.5 names ending with sato 29 7.6 Names ending with sawa 29 7.7 Names ending with shima 30 7.7 Names ending with ta 31 8. Discussion 33 8.1 Regional influence 33 8.2 Influence of morphemes 34 8.3 Names with the same first morpheme 37 8.4 Comparison with previous research 38 8.5 Problems and further research 39 9. Conclusion 40 Bibliography 41 2 1. Introduction During a trip to Hiroshima, a Japanese friend and I took a train in the direction of 糸崎. When I asked my friend if it was pronounced as Itozaki or Itosaki, she had to think for a while, eventually telling me that it probably was Itosaki. However, when the conductor announced the final station of the train five minutes later, it turned out to be Itozaki station. -

1 Linguistics 288B 12

Features: the atoms of segment structure Each feature encodes one of the aspects of speech production Linguistics 288b The specification of features is either positive or negative; specification is therefore binary/bivalent. Phonology 3 Features are conventionally arranged in a column called a feature matrix. Linguistics 288b 2 Features Why do we need features? [p] natural classes: an economical way of +consonantal characterizing segments (e.g. /s z S Z tS dZ/ = -syllabic [+sibilant]; /p t k b d g f v s z T D S Z tS dZ h // = -sonorant obstruents ([-sonorant, +consonantal]) -voice +labial better understanding of allophonic variation (e.g. -round assimilation - e.g. liquid devoicing /pr/ → [pr8] -continuant -nasal -lateral Linguistics 288b 3 Linguistics 288b 4 Allophonic variation Liquid devoicing Allophonic variation is not simply the substitution /p r/ →[pr8] of one allophone for another, but an +consonantal +consonantal -syllabic -syllabic ø environmentally conditioned change of a feature -sonorant +sonorant -voice +voice or features +labial +coronal /pr/ [p ] ‘pray’ [p ], ‘prime’ [p ] -continuant +continuant → r8 r8ej r8ajm -nasal -nasal -lateral -lateral etc. etc. Linguistics 288b 5 Linguistics 288b 6 1 Natural classes Natural classes Reason: simplicity in scientific modeling Examples of natural classes in English: (Occam’s razor). / s z S Z tS dZ/ = [+sibilant] /p t k b d g f v s z T D s z S Z tS dZ h // = [-sonorant, A set of segments is said to constitute a natural +consonantal] (obstruents) class if fewer features are needed to specify the /l/ = [+lateral] set as a whole then to specify any one member of the set. -

Phonotactically-Driven Rendaku in Surnames: a Linguistic Study Using Social Media

Phonotactically-DrivenRendakuinSurnames: ALinguisticStudyUsingSocialMedia YuTanaka 1. Introduction Like regular compound words, Japanese surnames with a compound structure can undergo a voicing alternation known as rendaku. Rendaku application in surnames is somewhat different from that in regular compounds, however; the voicing alternation is governed by avoidance of consonant sequences that are similar in terms of voicing and place. Although the peculiarity of rendaku in surnames has been noted in the literature (see Sugito, 1965 among others), no study has provided a full description or explanation of the patterns. The first aim of this study is thus to better describe the data. A corpus of rendaku in surnames is created using social media, which enables us to assess comprehensively and quantitatively the validity of proposed generalizations. The second aim of the study is to explain why rendaku applies in a different manner in names and in normal words. I propose that compound names are treated as if they are single stems and that the peculiar rendaku patterns in surnames can be attributed to stem-internal phonotactics, such as dispreferences for the occurrence of multiple voiced obstruents or sequential homorganic voiceless obstruents within stems. 2. Data: Rendaku in surnames 2.1. Strong Lyman’s Law? Rendaku, or sequential voicing (Martin, 1952), is a morphophonological process in Japanese whereby the initial obstruent of the second element of a compound becomes voiced,1 as shown in (1).2 (1) a. maki + susi ! maki-zusi ‘rolled-sushi’ b. ori + kami ! ori-gami ‘folding-paper’ Application of rendaku is variable, being affected by a number of factors including lexical idiosyncrasy (see Vance, 2015 for a comprehensive overview). -

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is The

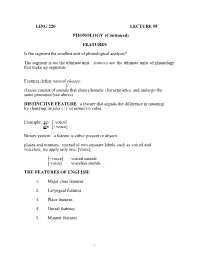

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? The segment is not the ultimate unit: features are the ultimate units of phonology that make up segments. Features define natural classes: ↓ classes consist of sounds that share phonetic characteristics, and undergo the same processes (see above). DISTINCTIVE FEATURE: a feature that signals the difference in meaning by changing its plus (+) or minus (-) value. Example: tip [-voice] dip [+voice] Binary system: a feature is either present or absent. pluses and minuses: instead of two separate labels, such as voiced and voiceless, we apply only one: [voice] [+voice] voiced sounds [-voice] voiceless sounds THE FEATURES OF ENGLISH: 1. Major class features 2. Laryngeal features 3. Place features 4. Dorsal features 5. Manner features 1 1. MAJOR CLASS FEATURES: they distinguish between consonants, glides, and vowels. obstruents, nasals and liquids (Obstruents: oral stops, fricatives and affricates) [consonantal]: sounds produced with a major obstruction in the oral tract obstruents, liquids and nasals are [+consonantal] [syllabic]:a feature that characterizes vowels and syllabic liquids and nasals [sonorant]: a feature that refers to the resonant quality of the sound. vowels, glides, liquids and nasals are [+sonorant] STUDY Table 3.30 on p. 89. 2. LARYNGEAL FEATURES: they represent the states of the glottis. [voice] voiced sounds: [+voice] voiceless sounds: [-voice] [spread glottis] ([SG]): this feature distinguishes between aspirated and unaspirated consonants. aspirated consonants: [+SG] unaspirated consonants: [-SG] [constricted glottis] ([CG]): sounds made with the glottis closed. glottal stop [÷]: [+CG] 2 3. PLACE FEATURES: they refer to the place of articulation. -

Table of Hiragana Letters Pdf

Table of hiragana letters pdf Continue Hiragana is one of three sets of characters used in Japanese. Each letter of Hiragana is a special syllable. The letter itself doesn't make sense. Hiragan is widely used to form a sentence. You can download/print the Hiragan chart (PDF) of all Hiragana's letters. The origin of Hiragan あ か た ま や the original 安 加 太 末 也 of Hiragan was developed in the 8th-10th century by simplifying the shape of specific kanji symbols. Compared to Katakana, Hiragana's letters have more curved lines. Number of letters In modern Japanese 46 basic letters of Hiragana. In addition to these 46 main letters, called gojon, there are modified forms to describe more time - 20 dakun, 5 handakuon, 36 y'on, 1 sokuon and 6 additional letters. Frequently asked questions: What are the letters with the bar on top ( Yap.) ? Gojaon 【五⼗⾳】 Goyon-【五⼗⾳図】 In Japanese, syllables are organized as a table (5 x 10). This table is called goj'on-zu (literally means a table of 50 sounds). The alphabets of Hiragan and Katakana are used to describe these sounds. Letters い, う and え appear more than once in the table. These 5 duplicates (grey) are usually missed or ignored. It includes ん syllable. It does not belong to any row or column. In total, 46 letters (45'1) are considered goj'on (50 sounds). You can learn the goj'on letters on the Hiragan course: Part 1-10. The structure of table First row - あ, い, う, え and お - five vowels of Japanese. -

Experimental Studies of Rendaku

8 Psycholinguistic Studies of Rendaku Shigeto Kawahara 8.1. Outline This chapter provides an overview of experimental studies of rendaku. The general spirit of these studies is to test whether rendaku and the factors that appear to affect its applicability are psychologically real. Experiments using nonce words and those that ask the participants to create new compounds address the question of whether patterns of rendaku are internalized in native speakers’ minds, i.e., grammaticalized. This spirit is clearly articulated in the first experimental study of rendaku (VANCE 1979). In §8.2, experiments that address the question of whether rendaku is a grammatical process or a lexicalized pattern are introduced. Next, §8.3 summarizes experiments on various specific aspects of rendaku, and then §8.4 discusses experimental approaches to Lyman’s Law (§3.2), as it relates to rendaku and beyond. Some remaining issues are taken up in §8.5. Experimental approaches are also central to research on the acquisition of rendaku, both by children learning Japanese natively and by students learning Japanese as a foreign language, but acquisition of rendaku is treated separately in Chapter 9. 8.2. Grammatical versus Lexical One of the most important questions about rendaku is whether it is a productive, phonological process or a lexicalized, analogical pattern (Kawahara 2015; Vance 2014). The first position assumes or asserts that rendaku is governed by the phonological component of grammar, and this is the position taken by most generative studies of rendaku (e.g. McCawley 1968:86–87; OTSU 1980; ITÔ and MESTER 1986, 1995: 819, 2003a:Chapter 4, 2003b; MESTER and ITÔ 1989: 277-279; KURODA 2002; Kurisu 2007, among others; see Chapter 7). -

Postnasal Voicing, Japanese Rendaku, and the Naturalness Condition

Vance, Timothy Postnasal Voicing, Japanese Rendaku, and the Naturalness Condition 1. Postnasal Voicing A nasal immediately followed by a voiceless obstruent is generally considered marked (i.e., dispreferred) for both articulatory reasons (Huffman 1993) and perceptual reasons (Ohala and Ohala 1993). The assimilatory pressure that repairs such sequences or prevents them from arising in the first place is commonly called postnasal voicing (PNV) and is attributed by OT enthusiasts to a (putatively universal) constraint such as *NC̥ (Kager 1999). 2. Rendaku In modern Tokyo Japanese (MTJ), many morphemes beginning with an obstruent have one allomorph in which the initial obstruent is voiceless and another in which it is voiced. An ex- ample is /tana/~/dana/ ‘shelf’, which begins with /t/ as a word on its own but with /d/ as the second element in the compound /iwa+dana/ ‘rock ledge’ (cf. /iwa/ ‘rock’). The initial voiced obstruent in /dana/ is an instance of rendaku ‘sequential voicing’. In /t/~/d/ the alternation in- volves only voicing ([t]~[d]), but in other cases a voiceless obstruent and its rendaku partner differ in more than just voicing (Vance 2015), as shown in (1). (1) a. /f/~/b/ ([ɸ]~[b]) d. /č/~/ǰ/ ([tɕ]~[dʑ]) g. /š/~/ǰ/ ([ɕ]~[dʑ]) b. /h/~/b/ ([h]/[ç]~[b]) e. /c/~/z/ ([ts]~[dz]/[z]) h. /k/~/g/ ([k]~[ɡ]/[ŋ]) c. /t/~/d/ ([t]~[d]) f. /s/~/z/ ([s]~[dz]/[z]) The moraic kana subsystems of the Japanese writing system (hiragana and katakana) rep- resent the rendaku alternations in (1) in a uniform way, using a diacritic called dakuten: 〈゙〉. -

Pdf (Accessed on 02 February 2007)

Features in Phonology1 Maria Gouskova Contents 1 What are features? 2 2 The main features 3 2.1 Manner features . 3 2.1.1 Consonantal . 3 2.1.2 Sonorant . 4 2.1.3 Nasal . 5 2.1.4 Continuant . 6 2.2 Laryngealfeatures...................................................... 7 2.2.1 Voice . 7 2.2.2 Spread glottis . 8 2.2.3 Constricted glottis . 8 2.3 Place features . 9 2.3.1 Labial ........................................................ 9 2.3.2 Coronal . 10 2.3.3 Dorsal . 11 3 Vocalic features 11 3.1 Round . 11 3.2 Back............................................................. 12 3.3 Height . 12 3.4 ATR ............................................................. 13 4 Minor features 14 4.1 Minor consonantal features . 14 4.1.1 Lateral........................................................ 14 4.1.2 Strident . 14 4.1.3 Anterior . 15 4.1.4 Secondary articulations on consonants . 15 5 Controversial distinctions 16 5.1 Consonantal distinctions . 17 5.1.1 Glides vs. vowels . 17 5.1.2 Approximants as a class . 18 5.1.3 Exoticdistinctionsamongcoronals . 19 5.1.4 Affricates ...................................................... 19 5.1.5 Labialsandtrills................................................... 20 5.1.6 Pharyngeals and glottals . 20 5.1.7 Laryngealcontroversies ............................................... 21 5.2 Vocalic distinctions . 22 5.2.1 DoesEnglishhaveanATRdistinction?. 22 5.2.2 The featural status of central vowels . 22 5.2.3 How to characterize length contrasts . 23 6 Are features privative, binary, or multivalued? 24 7 Same pattern, different sound? 25 8 Are features innate or learned? 25 9 How to write rules, SPE-style 26 10 Conclusion 27 1 Maria Gouskova Phonology I, NYU 1 What are features? When we talk about sounds in a phonetics or phonology class, we usually use phonetic terms to describe them: alveolar, palatal, interdental, trill. -

Distinctive Feature

24.901Page 1 Feature review; natural classes (1) Distinctive feature: an articulatory/acoustic property that classifies speech sounds (2) Some examples: Feature name Defining properties [+F] [-F] [nasal] Velum position Velum down Velum up m, n, N, a), e), o), j) ,r)... b, d, g, a, e, o, j, r… [voice] Vocal chord vibration Yes No b, d, g, v, z, Z, vowels, p, t, k, s, S, f, h nasals, l, r, glides [aspirated] Glottis held wide open Yes No ([spread glottis]) h, pÓ, tÓ, kÓ, voiceless All others fricatives [coronal] Tip or blade of tongue Tip/blade involved Tip/blade not involved in articulation involved t, s, S, T, l, n… p, k, h, a, w, j… [anterior] Constriction site relative At or in front of ridge Behind ridge to alveolar ridge p, f, t, s, T, d, l, m, n k, S, tS, j, N, :, λ [lateral] Sides of tongue position Lowered Not lowered l, :, L, λ All others, incl. r [consonantal] Contact between Yes No articulators or significant narrowing of vocal tract Stops, fricatives, Vowels, glides (j, w), affricates, nasals, l, h, / varieties of [r] [continuant] Airflow through mouth Yes No Fricatives, laterals, r, Stops, affricates, / glides, vowels, h [syllabic] Center or margin of Center Margin syllable Vowels, r`, m`, n`, l`, s` Glides, other C’s [sonorant] Continuity of spectrum Continuity Discontinuity amplitude in F1-F2 region Nasals, laterals, r, Stops, fricatives, glides, vowels affricates, glottal stop [back] Site of tongue body Back Front constriction u, o, ¨, A, :, w and i, e, y, œ, j uvulars (q, R) 1 24.901Page 2 Feature name Defining properties [+F] [-F] [round] Lip pursing Yes No o, O, u, U, y, w, kw All others [low] Jaw position Lowered Not lowered a, œ, A All others [high] Tongue body vertical Raised Not raised position i, u, y, ¨, j, w, velar C’s All others (3) Speech sounds are bundles of distinctive features.