Vegetarian Diets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition and the Cancer Survivor

NUTRITION AND THE CANCER SURVIVOR CANCER SURVIVOR SERIES AICR Research Grants 2015 (partial list) CONTENTS Women’s interventional nutrition study (WINS) long- term survival analysis 1 Introduction . 2 Rowan Chlebowski, MD, PhD, Harbor-UCLA Medical Diet and Cancer . 3 Center Weight and Cancer . 4 . Gene-environment interactions among circulating vitamin D levels, vitamin D pathway gene Physical Activity and Cancer . 4 . polymorphisms, BMI and esophageal adenocarcinoma prognosis 2 Adopting a Healthy Lifestyle . 5 David Christiani, MD, PhD, Harvard University Tips for Healthy Eating . .5 . Targeted disruption of cancer cell metabolism and Handle Food Safely . 8 growth through modification of diet quality Barbara Gower, PhD, The University of Alabama at Watch Your Waist . .9 . Birmingham Be Physically Active . 12 A mail- and video-based weight loss trial in breast cancer survivors 3 Evaluating Nutrition Information . 13 Melinda L . Irwin, PhD, Yale University 4 Common Questions . 16 Effects of fish oil on lipid metabolites in breast cancer Greg Kucera, PhD, Wake Forest University Health Should I take supplements? . .16 . Sciences Will a vegetarian diet protect me? . 17 Impact of physical activity on tumor gene expression What about eating only organic foods? . 17 . in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer Jennifer Ligibel, MD, Dana Farber Cancer Institute Are macrobiotic diets advisable? . 18. Impact of resistance training and protein 5 Need More Help? . 19 supplementation on lean muscle mass among childhood cancer survivors About AICR . .22 . Kirsten Ness, PhD, St . Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital About The Continuous Update Project . 22 Pilot study of a metabolic nutritional therapy for the AICR Recommendations for Cancer management of primary brain tumors Prevention . -

The Food Pyramid and the Environmental Pyramid Andrea Poli Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition

Roma, 5 novembre 2010 The Food Pyramid and the Environmental Pyramid Andrea Poli Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition We are aware that correct nutrition is essential to health. Development and modernization have made available to an increasing number of people a varied and abundant supply of foods. Our genes, however, maintains the “efficient” attitude (thrifty genotype) selected by evolution. Without a proper cultural foundation or clear nutritional guidelines that can be applied and easily followed on a daily basis, individual, especially in the West, risk following unbalanced –if not actually incorrect- eating habits. 2 Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition The rapid increase of obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer are now the biggest problem for public health in our society, and it also has enormous socio-economic impact Health spending in the USA 5000 4.400 miliardi di Dollari The longer life 4000 expectancy 3000 increases the 2.500 miliardi possibility that risk 2000 di Dollari factors became pathologies 1000 0 1980 1990 2010 2018 3 Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition First: investment in prevention The health spending does not guarantee a healthy life expectancy (in the absence of chronic degenerative diseases) It is estimated that 1€ of investment in prevention could save 3€ for less expenditure on disease treatment (estimated forecast) 4 Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition NUTRITION and LIFESTYLE are the two factors that can have more influence not only on longevity, but also on quality of life. 5 Barilla Center -

Descargar Libro Completo

2013 2014 2015 2016 Barcelona, 2018 2017 ACTOS INTERNACIONALES EN BARCELONA Real Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Financieras DESAFÍOS DE LA NUEVA SOCIEDAD SOBRECOMPLEJA: HUMANISMO, TRANSHUMANISMO, DATAÍSMO Y OTROS ISMOS CHALLENGES OF THE NEW OVERCOMPLEX SOCIETY: HUMANISM, TRANSHUMANISM, DATAISM AND OTHER ISMS XIII ACTO INTERNACIONAL DE LA REAL ACADEMIA DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y FINANCIERAS Barcelona, 15 y 16 de noviembre de 2018 DESAFÍOS DE LA NUEVA SOCIEDAD SOBRECOMPLEJA: HUMANISMO, TRANSHUMANISMO, DATAÍSMO Y OTROS ISMOS XIII Acto Internacional de la Real Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Financieras La realización de esta publicación ha sido posible gracias a con la colaboración de con el patrocinio de 27 de mayo de 2014 DESAFÍOS DE LA NUEVA SOCIEDAD SOBRECOMPLEJA: HUMANISMO, TRANSHUMANISMO, DATAÍSMO Y OTROS ISMOS XIII Acto Internacional de la Real Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Financieras Publicaciones de la Real Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Financieras Real Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Financieras Desafíos de la nueva sociedad sobrecompleja: humanismo, transhumanismo, dataísmo y otros ismos. XIII Acto Internacional / Real Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Financieras. Bibliografía ISBN- 978-84-09-08674-0 I. I. Título II. Gil Aluja, Jaime III. Colección 1. Economía mundial. 2. Tecnología e innovación 3. Biología humana 4. Bigdata La Academia no se hace responsable de las opiniones científicas expuestas en sus propias publicaciones. (Art. 41 del Reglamento) Editora: © Real Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Financieras, Barcelona, 2019 Académico Coordinador: Dra. Anna Maria Gil-Lafuente ISBN- 978-84-09-08674-0 Depósito legal: B 4985-2019 Esta publicación no puede ser reproducida, ni total ni parcialmente, sin permiso previo, por escrito de la editora. -

The Healthful Soybean

FN-SSB.104 THE HEALTHFUL SOYBEAN Soy protein bars, soy milk, soy cookies, soy burgers .…. the list of soy products goes on. Soybeans are best known as a source of high quality protein. They are also rich in calcium, iron, zinc, vitamin E, several B-vitamins, and fiber. But in 1999, soy took the nation by storm. The Food and Drug Administration approved health claims that soy protein may lower the risk of heart disease if at least 25 grams of soy protein are consumed daily. This benefit may be because soybeans are low saturated fat, have an abundance of omega-3 fatty acids, and are rich in isoflavones. Research continues to explore health benefits linked to the healthful soybean. Beyond research, edamame, tempeh, tofu, and soy milk make the base for some truly delectable dishes. Exploring Soyfoods Fresh Green Soybeans Edamame (fresh green soybeans) have a sweet, buttery flavor and a tender-firm texture. Fresh soybeans still in the pod should be cooked and stored in the refrigerator. Handle frozen soybeans as you would any other frozen vegetable. The easiest way to cook washed, fresh soybeans in the pod is to simmer them in salted water for 5 minutes. Once the beans are drained and cooled, remove them from the pod. Eat as a snack or simmer an additional 10 to 15 minutes to use as a side dish. Substitute soybeans for lima beans, mix the beans into soups or casseroles in place of cooked dried beans, or toss the beans with pasta or rice salads. Dried Soybeans Dried mature soybeans are cooked like other dried beans. -

Sprout Lady Rita's Step-By-Step Guide To

SPROUT LADY RITA’S STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE TO SPROUTING HOW TO SPROUT IN A MASON JAR USING A STAINLESS- STEEL SCREEN OR PLASTIC SPROUTING LID 1. Follow safe food-handling procedures by washing the jar and screen or lid in warm sudsy water and then rinse in hot water; use clean water from a reliable source for soaking and sprouting. Wash your hands before touching the seeds or sprouts. 2. Measure your seeds/beans and put them in the jar. 3. Fill the jar with cool water. 4. Soak the seeds/beans in the jar overnight, about 8 to10 hours. 5. Screw the screen and rim or plastic lid onto the mason jar. Pour out the water so that you are left with only wet seeds/beans in the jar and no standing water. 6. Fill the jar with fresh water. Give the seeds/beans a minute or so and let them absorb the water and enjoy their bath. Pour out the water so that you are left with only wet seeds/beans in the jar and no standing water. 7. Place the jar upside down at an angle with the screen or lid on the bottom to allow the water to fully drain out. 8. Approximately every 12 hours, at least two times each day, rinse and drain the seeds/beans, making certain that there is no standing water left in the jar, only wet seeds/beans or sprouts. Be consistent in your rinsing and draining; the sprouts will grow very nicely if you remember to give them their baths. -

Using Fast Food Nutrition Facts to Make Healthier Menu Selections

Teaching Idea Using Fast Food Nutrition Facts to Make Healthier Menu Selections Jennifer Turley ABSTRACT Objectives: This teaching idea enables students to (1) access and analyze fast food nutrition facts information (Calorie, total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sugar, and sodium content); (2) decipher unhealthy and healthier food choices from fast food restaurant menus for better meal and diet planning to reduce obesity and minimize disease risk; and (3) discuss consumer tips, challenges, perceptions, and needs regarding fast foods. Target Audience: Junior high, high school, or college students, with appropriate levels of difficulty included in this paper. Turley J. Using fast food nutrition facts to make healthier menu selections. Am J Health Educ. 2009;40(6):355-363. INTRODUCTION overarching goals of the Dietary Guidelines Association recently advised families to Obesity is a national and worldwide for Americans 2005, which are also echoed limit the consumption of meals outside the concern.1,2 In the United States, childhood, in the MyPyramid food guidance system, home.5 Nearly all health experts, public and adolescent, and adult obesity has steadily along with the 2006 dietary recommenda- private, agree that overweight and obesity increased. In 2007, about two-thirds (67%) tions from the American Heart Association happens when a person is in positive energy of all Americans were either overweight or and the American Cancer Society.3, 6-9 balance from chronically and consistently obese.3 Further, more children are currently Most fast food restaurants publish the consuming more Calories than they expend. in higher overweight percentile rankings, nutrition facts information on their website. -

Plant-Based Milk Alternatives

Behind the hype: Plant-based milk alternatives Why is this an issue? Health concerns, sustainability and changing diets are some of the reasons people are choosing plant-based alternatives to cow’s milk. This rise in popularity has led to an increased range of milk alternatives becoming available. Generally, these alternatives contain less nutrients than cow’s milk. In particular, cow’s milk is an important source of calcium, which is essential for growth and development of strong bones and teeth. The nutritional content of plant-based milks is an important consideration when replacing cow’s milk in the diet, especially for young children under two-years-old, who have high nutrition needs. What are plant-based Table 1: Some Nutrients in milk alternatives? cow’s milk and plant-based Plant-based milk alternatives include legume milk alternatives (soy milk), nut (almond, cashew, coconut, macadamia) and cereal-based (rice, oat). Other ingredients can include vegetable oils, sugar, and thickening ingredients Milk type Energy Protein Calcium kJ/100ml g/100ml mg/100ml such as gums, emulsifiers and flavouring. Homogenised cow’s milk 263 3.3 120 How are plant-based milk Legume alternatives nutritionally Soy milk 235-270 3.0-3.5 120-160* different to cow’s milk? Nut Almond milk 65-160 0.4-0.7 75-120* Plant-based milk alternatives contain less protein and Cashew milk 70 0.4 120* energy. Unfortified versions also contain very little calcium, B vitamins (including B12) and vitamin D Coconut milk** 95-100 0.2 75-120* compared to cow’s milk. -

Diet Therapy and Phenylketonuria 395

61370_CH25_369_376.qxd 4/14/09 10:45 AM Page 376 376 PART IV DIET THERAPY AND CHILDHOOD DISEASES Mistkovitz, P., & Betancourt, M. (2005). The Doctor’s Seraphin, P. (2002). Mortality in patients with celiac dis- Guide to Gastrointestinal Health Preventing and ease. Nutrition Reviews, 60: 116–118. Treating Acid Reflux, Ulcers, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Shils, M. E., & Shike, M. (Eds.). (2006). Modern Nutrition Diverticulitis, Celiac Disease, Colon Cancer, Pancrea- in Health and Disease (10th ed.). Philadelphia: titis, Cirrhosis, Hernias and More. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. Nevin-Folino, N. L. (Ed.). (2003). Pediatric Manual of Clin- Stepniak, D. (2006). Enzymatic gluten detoxification: ical Dietetics. Chicago: American Dietetic Association. The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Trends in Niewinski, M. M. (2008). Advances in celiac disease and Biotechnology, 24: 433–434. gluten-free diet. Journal of American Dietetic Storsrud, S. (2003). Beneficial effects of oats in the Association, 108: 661–672. gluten-free diet of adults with special reference to nu- Paasche, C. L., Gorrill, L., & Stroon, B. (2004). Children trient status, symptoms and subjective experiences. with Special Needs in Early Childhood Settings: British Journal of Nutrition, 90: 101–107. Identification, Intervention, Inclusion. Clifton Park: Sverker, A. (2005). ‘Controlled by food’: Lived experiences NY: Thomson/Delmar. of celiac disease. Journal of Human Nutrition and Patrias, K., Willard, C. C., & Hamilton, F. A. (2004). Celiac Dietetics, 18: 171–180. Disease January 1986 to March 2004, 2382 citations. Sverker, A. (2007). Sharing life with a gluten-intolerant Bethesda, MD: United States National Library of person: The perspective of close relatives. -

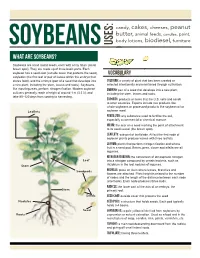

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Revista Española De Nutrición Humana Y Dietética Spanish Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics

Rev Esp Nutr Hum Diet. 2020; 24(1). doi: 10.14306/renhyd.24.1.953 [ahead of print] Freely available online - OPEN ACCESS Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética Spanish Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics INVESTIGACIÓN versión post-print Esta es la versión aceptada. El artículo puede recibir modificaciones de estilo y de formato. Vegetarian dietary guidelines: a comparative dietetic and communicational analysis of eleven international pictorial representations Guías alimentarias vegetarianas: análisis comparativo dietético y comunicacional de once representaciones gráficas internacionales Chiara Gai Costantinoa*, Luís Fernando Morales Moranteb. a CEU Escuela Internacional de Doctorado, Universitat Abat Oliba CEU. Barcelona, Spain. b Departamento de Publicidad, Relaciones Públicas y Comunicación Audiovisual, Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Cerdanyola del Vallès, Spain. * [email protected] Received: 14/10/2019; Accepted: 08/03/2020; Published: 30/03/2020 CITA: Gai Costantino C, Luís Fernando Morales Morante LF. Vegetarian dietary guidelines: a comparative dietetic and communicational analysis of eleven international pictorial representations. Rev Esp Nutr Hum Diet. 2020; 24(1). doi: 10.14306/renhyd.24.1.953 [ahead of print] La Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética se esfuerza por mantener a un sistema de publicación continua, de modo que los artículos se publican antes de su formato final (antes de que el número al que pertenecen se haya cerrado y/o publicado). De este modo, intentamos p oner los artículos a disposición de los lectores/usuarios lo antes posible. The Spanish Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics strives to maintain a continuous publication system, so that the articles are published before its final format (before the number to which they belong is closed and/or published). -

Sprout Production in California

PUBLICATION 8060 Sprout Production in California WAYNE L. SCHRADER, University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, San Diego County Sprouts have been used for food since before recorded history. Sprouts vary in texture and taste. Some are spicy (e.g., radish and onions), some are used in Asian foods (e.g., mung bean [Phaseolus aureus]), and others are delicate (e.g., alfalfa) and are UNIVERSITY OF used in salads and sandwiches to add texture. Vegetable sprouts grown for food are CALIFORNIA baby plants that are harvested just after germination. Various crop seeds may be Agriculture sprouted. The most common are adzuki, alfalfa, buckwheat, Brassica spp. (broccoli, and Natural Resources etc.), cabbage, clover, cress, garbanzo, green peas, lentils, mung bean, radish, rye, http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu sesame, wheat, and triticale. Production practices should provide appropriate ger- mination conditions, moisture, and temperatures that allow for the “harvesting” of the sprouts at their optimal eating quality. Production practices should also allow for efficient cleaning and packaging of sprouts. VARIETIES Mung bean seed are used to produce bean sprouts; some soybeans and adzuki beans are also used to produce bean sprouts. The preferred varieties are those that have smaller-sized seed. With small seed, the cotyledons and seed coats are less objec- tionable or are more easily removed from the finished product. The smallest-seeded varieties of mung bean are Oklahoma 12 and Oriental; larger-seeded types are Jumbo and Berken. Any small-seeded adzuki may be used for sprouts; a variety called Chinese Red Adzuki is sometimes substituted for adzuki bean even though it is not a true adzuki bean. -

Review of the China Study

FACT SHEET REVIEW OF THE CHINA STUDY By Team, General Conference Nutrition Council In 1905 Ellen White described the diet our Creator chose for us as a balanced plant-based diet including foods such as grains, fruit and vegetables, and nuts (1). Such a diet provides physical and mental vigor and endurance. She also recognized that such a diet may need to be adjusted according to the season, the climate, occupation, individual tolerance, and what foods are locally available (2). The General Conference Nutrition Council (GCNC) therefore recommends the consumption of a balanced vegetarian diet consisting of a rich variety of plant-based foods. Wherever possible those should be whole foods. Thousands of peer-reviewed research papers have been published over the last seven decades validating a balanced vegetarian eating plan. With so much support for our advocacy of vegetarian nutrition we have no need to fortify our well-founded position with popular anecdotal information or flawed science just because it agrees with what we believe. The methods used to arrive at a conclusion are very important as they determine the validity of the conclusion. We must demonstrate careful, transparent integrity at every turn in formulating a sound rationale to support our health message. It is with this in mind that we have carefully reviewed the book, The China Study (3). This book, published in 2004, was written by T. Colin Campbell, PhD, an emeritus professor of Nutritional Biochemistry at Cornell University and the author of over 300 research papers. In it Campbell describes his personal journey to a plants-only diet.