Inquiry Into Water Use Efficiency in Australian Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embracing Change Murray Irrigation Annual Report 2014

Embracing change Murray Irrigation Annual Report 2014 Murray Irrigation Contents At a glance 2 Chairman’s report 4 Chief Executive Officer’s report 6 Year in review 8 Company profile and management team 10 Chapters 01 Customers 12 02 Water availability, usage and efficiency 18 03 Infrastructure 22 04 Financial performance 28 05 Ancillary activities 32 06 People and governance 36 Directors’ report and financial statements 2013/14 44 Directors’ report 46 Financial statements 54 Directors’ declaration 80 Auditor’s independence declaration 81 Independent audit report 82 2014 Murray Irrigation Limited Annual Report The 2014 Murray Irrigation Limited Annual Report is a summary of operations and performance of the company from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. Operations and performance for this period have been measured against the company’s key reporting areas as detailed in the Murray Irrigation Limited 2014 Strategic Plan in addition to meeting our statutory financial reporting responsibilities. The 2014 Murray Irrigation Limited Annual Report provides a concise and comprehensive summary. The objective of this report is to provide information to our shareholders to demonstrate our transparency, accountability and performance. The 2014 Murray Irrigation Limited Annual Report is distributed on request to all shareholders and is available electronically via our website, as per the requirements of our Constitution. Additional copies of the 2014 Murray Irrigation Limited Annual Report can be obtained via: • The Murray Irrigation Limited website www.murrayirrigation.com.au • Visiting the Murray Irrigation offices at Deniliquin and Finley. • Writing to Murray Irrigation Limited, PO Box 528, Deniliquin NSW 2710. Murray Irrigation is on a progressive change journey. -

Water Recovery in the Murray Irrigation Area of Nsw

Disclaimer This report has been generated as part of the Living Murray initiative. Its contents do not represent the position of the Murray-Darling Basin Commission. It is presented as a document which informed discussion for improved management of the Basin’s natural resources in November 2003. Preparation of the social impact assessment scoping and profiling studies preceded the Living Murray First Step decision and the signing on 25 June 2004 at the Council of Australian Governments meeting of the Intergovernmental Agreement on Addressing Water Overallocation and Achieving Environmental Objectives in the Murray- Darling Basin. The communiqué from this COAG meeting is provided at www.coag.gov.au. These decisions provide the framework under which $500m will be invested by governments over 5 years to begin addressing water overallocation in the Murray-Darling Basin and achieve specific environmental outcomes in the Murray-Darling Basin. The first priority for this investment will be water recovery for six significant ecological assets first identified by the Murray-Darling Basin Ministerial Council in November 2003: the Barmah-Millewa Forest, Gunbower and Koondrook-Perricoota Forests, Hattah Lakes, Chowilla floodplain, the Lindsay-Wallpolla system, the Murray Mouth, Coorong and Lower Lakes, and the River Murray Channel. The water will come from a matrix of options with a priority for on-farm initiatives, efficiency gains, infrastructure improvements and rationalisation, and market based approaches, and purchase of water from willing sellers, rather than by way of compulsory acquisition. Consequently, the assumptions that were made to enable the social impact assessment scoping and profiling studies to be undertaken in mid 2003, while reasonable at the time, have been overtaken by these decisions and the consequential benefits that will flow from them. -

Myth & the Murray

Myth & the Murray Measuring the real state of the river environment by Jennifer Marohasy We have all heard about the declining health of the Murray River, including poor water quality, dying red gums and threats to the continued survival of the Murray cod—this is the popular view in urban Australia. Along the river, communities believe that the end of commercial fishing, a substantial restocking effort, improvements in on-farm practices and the construction of salt-interception schemes have resulted in a healthier river. The available evidence supports the local view and suggests that, with the possible exception of native fish stocks, the river environment is healthy. Many of the scientific reports that have led to the perception that the Murray River is in poor health make their comparisons with a natural river, which is one without dams and locks, one that gushes and then runs dry. Such comparisons are misplaced. If the ultimate objective of the conservation movement is a natural river, then we must reject the cultural heritage and economic wealth created by the engineering works, including the Snowy Mountains Scheme. In its natural state, the Murray River could not provide for Adelaide’s water needs and it could not support the irrigation industries that have made the region the food bowl of Australia. Backgrounder December 2003, Vol. 15/5, rrp $22.00 Myth & the Murray: Measuring the real state of the river environment 2. INTRODUCTION buy the total amount of water proposed (1,500 gigalitres). ‘Myths embody popular ideas on natural and While spending money on the environment may social phenomena.’ seem like a worthy cause in itself, what would actually Oxford English Dictionary be achieved if this quantity of water were released? The Murray River environment is highly modified as In Australian cities, a popular idea about the Murray a consequence of the many dams and locks constructed River has emerged. -

2016 National Plant Biosecurity Status Report

The National Plant Biosecurity Status Report 2016 © Plant Health Australia 2017 Disclaimer: This publication is published by Plant Health Australia for information purposes only. Information in the document is drawn from a variety of sources outside This work is copyright. Apart from any use as Plant Health Australia. Although reasonable care was taken in its preparation, Plant Health permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part Australia does not warrant the accuracy, reliability, completeness or currency of the may be reproduced by any process without prior information, or its usefulness in achieving any purpose. permission from Plant Health Australia. Given that there are continuous changes in trade patterns, pest distributions, control Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction measures and agricultural practices, this report can only provide a snapshot in time. and rights should be addressed to: Therefore, all information contained in this report has been collected for the 12 month period from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2016, and should be validated and Communications Manager confirmed with the relevant organisations/authorities before being used. A list of Plant Health Australia contact details (including websites) is provided in the Appendices. 1/1 Phipps Close DEAKIN ACT 2600 To the fullest extent permitted by law, Plant Health Australia will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred in or arising by reason of any person relying on the ISSN 1838-8116 information in this publication. Readers should make and rely on their own assessment An electronic version of this report is available for and enquiries to verify the accuracy of the information provided. -

Murray-Darling Basin Authority 2012A)

Murray–Darling Basin 7. Murray–Darling Basin ................................................. 2 7.5.4 Flooding ............................................... 31 7.1 Introduction ........................................................ 2 7.5.5 Storage systems ................................... 33 7.2 Key information .................................................. 3 7.5.6 Wetlands .............................................. 35 7.3 Description of the region .................................... 4 7.5.7 Hydrogeology ....................................... 41 7.3.1 Physiographic characteristics.................. 6 7.5.8 Watertable salinity ................................. 41 7.3.2 Elevation ................................................. 7 7.5.9 Groundwater management units ........... 44 7.3.3 Slopes .................................................... 8 7.5.10 Status of selected aquifers .................... 48 7.3.4 Soil types ................................................ 9 7.6 Water for cities and towns ................................ 62 7.3.5 Land use .............................................. 11 7.6.1 Urban centres ....................................... 62 7.3.6 Population distribution .......................... 13 7.6.2 Sources of water supply ....................... 64 7.3.7 Rainfall zones ....................................... 14 7.6.3 Canberra and Queanbeyan ................... 64 7.3.8 Rainfall deficit ....................................... 15 7.7 Water for agriculture ........................................ -

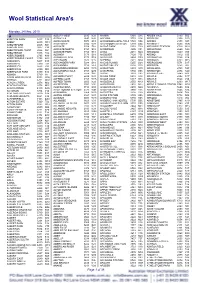

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

Water Resources and Waste Water Disposal

INDUSTRY COMMISSION WATER RESOURCES AND WASTE WATER DISPOSAL REPORT NO. 26 17 JULY 1992 Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 1992 ISBN 0 644 25500 5 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries Concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Commonwealth Information Services, Australian Government Publishing Service, GPO BOX 84, Canberra ACT 2601. Printed in Australia by P . J . GRILLS, Commonwealth Government Printer, Canberra INDUSTRY COMMISSION 17 April 1992 The Honourable J Dawkins, M P Treasurer Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Treasurer In accordance with Section 7 of the Industry Commission Act 1989, we have pleasure in submitting to you the Commission’s final report on Water Resources and Waste Water Disposal. Yours sincerely M L Parker Presiding Commissioner T J Hundloe D R Chapman Commissioner Associate Commissioner COMMISSIONER Benjamin Offices, Chan Street, Belconnen ACT Australia PO BOX, Belconnen ACT 2616 Telephone: 06 264 1144 Facsimile: 06 253 1662 Acknowledgment The commission wishes to thank those staff members who contributed to this report. IV WATER RESOURCES & WASTE WATER DISPOSAL CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS ix PART I : MAIN REPORT TERMS OF REFERENCE xix OVERVIEW AND RECOMMENDATIONS 1 1. THE INQUIRY 21 1.1 Scope of the inquiry 21 1.2 The water sector 22 1.3 The Commission’s approach 27 2. PRICING PRACTICES AND PERFORMANCE 31 2.1 Pricing of urban WSD services 31 2.2 Pricing of irrigation water 40 2.3 Participants’ views on shortcomings in current pricing 43 2.4 Institutional arrangements affect pricing policies 46 3. -

River Red Gums and Woodland Forests Riverina Bioregion Regional Forest Assessment: River Red Gum and Other Woodland Forests

DECEMBER 2009 FINAL ASSESSMENT REPORT RIVerina BIOREGION REGIOnal FOREST ASSESSMENT RIVER RED GUMS AND WOOdland FORESTS Riverina Bioregion Regional Forest Assessment: River red gum and other woodland forests Enquiries Further information regarding this report can be found at www.nrc.nsw.gov.au Enquiries can be directed to: Bryce Wilde Ph: 02 8227 4318 Email: [email protected] Daniel Hoenig (media enquiries) Ph: 02 8227 4303 Email: [email protected] By mail: Forests Assessment Natural Resources Commission GPO Box 4206 Sydney NSW 2001 By fax: 02 8227 4399 This work is copyright. The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study, research, news reporting, criticism and review. Selected passages, table or diagrams may be reproduced for such purposes provided acknowledgement of the source is included. Printed on ENVI Coated paper, which is made from elemental chlorine-free pulp derived from sustainably-managed forests and non-controversial sources. It is Australian made and certified carbon neutral from an ISO 14001 accredited mill which utilises renewable energy sources. All photographs are by the Natural Resources Commission unless otherwise acknowledged. Document No. D09/4554 ISBN: 978 1 921050 54 1 Print management by e2e (www.e2em.com.au) GIS services by Ecological Australia Commissioner’s foreword The Riverina bioregion is a treasured part of Australia, with its winding rivers and floodplain forests, its rich agricultural land, and its cultural significance to Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The region’s floodplains, and the river red gum forests they have supported for thousands of years, are an integral part of the natural landscape and the social fabric of the region. -

Regional Freight Transport Plan November 2019 Regional Freight Transport Plan

REGIONAL FREIGHT TRANSPORT PLAN NOVEMBER 2019 REGIONAL FREIGHT TRANSPORT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................................................3 Our Goals and Strategies.............................................................................................................................................................6 PART ONE: INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................................................7 Major Grain Freight Routes and Modals.....................................................................................................................10 Major Livestock Freight Routes and Modals............................................................................................................11 Major Timber/Pulp and Paper Freight Routes and Modals.........................................................................12 HML Routes.............................................................................................................................................................................................13 PART TWO: ABOUT THIS PLAN.......................................................................................................................................................................15 ASSESSMENT OF ROUTE CONSTRAINTS.....................................................................................................................16 -

1 1. Title of the Measure Improved Flow Management Works at The

Amendment date: 30 August 2017 1. Title of the measure Improved flow management works at the Murrumbidgee Rivers – Yanco Creek off-take 2. Proponent undertaking the measure NSW 3. Type of measure Supply 4. Requirements for notification a) The measure will be in operation by 30 June Yes 2024 b) The measure is not an ‘anticipated measure’ Yes ‘Anticipated measure’ is defined in section 7.02 of the It is a new measure (not already included in the Basin Plan to mean ‘a measure that is part of the benchmark conditions). benchmark conditions of development’. c) NSW agrees with the notification Yes 5. Surface water SDL resource units affected by the measure This measure identifies all surface water resource units in the Southern Basin region as affected units for the purposes of notifying supply measures. The identification of affected units does not constitute an agreement between jurisdictions on apportioning the supply contribution, which will be required in coming months. 6. Details of relevant constraint measures The Murrumbidgee constraints management strategy (see separate supply measure notification) will improve the ability to release water from storages to create higher flows along the Murrumbidgee River. The improved flow management works set out in the Improved flow management works at the Murrumbidgee Rivers – Yanco Creek off-take measure, will further improve the environmental outcomes for the mid- Murrumbidgee wetlands. 7. Date on which the measure will enter into operation The date by which the measure will enter into operation is 30 June 2024. 8. Details of the measure a) Description of the works or measures that The proposed works include: constitute this measure a) Yanco Creek Regulator and Fishway – a new regulator to be installed in Yanco Creek to allow regulation of flows between the Murrumbidgee River and Yanco Creek. -

The Canberra Fisherman

The Canberra Fisherman Bryan Pratt This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. The Canberra Fisherman The Canberra Fisherman Bryan Pratt Australian National University Press, Canberra, Australia, London, England and Norwalk, Conn., USA 1979 First published in Australia 1979 Printed in Australia for the Australian National University Press, Canberra © Bryan Pratt 1979 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Pratt, Bryan Harry. The Canberra fisherman. ISBN 0 7081 0579 3 1. Fishing — Canberra district. I. Title. 799.11’0994’7 [ 1 ] Library of Congress No. 79-54065 United Kingdom, Europe, Middle East, and Africa: books Australia, 3 Henrietta St, London WC2E 8LU, England North America: books Australia, Norwalk, Conn., USA southeast Asia: angus & Robertson (S.E. Asia) Pty Ltd, Singapore Japan: united Publishers Services Ltd, Tokyo Text set in 10 point Times and printed on 85 gm2semi-matt by Southwood Press Pty Limited, Marrickville, Australia. Designed by Kirsty Morrison. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix The Fish 1 Streams 41 Lakes and Reservoirs 61 Angling Techniques 82 Angling Regulationsand Illegal Fishing 96 Tackle 102 Index 117 Maps drawn by Hans Gunther, Cartographic Office, Department of Human Geography, Australian National University Acknowledgments I owe a considerable debt to the many people who have contributed to the writing of this book. -

Riverina Murray Region – Agricultural Profile

Introduction to IAL Mapping The Department of Primary Industries, The NSW Department of Primary Industries is Agriculture has developed a consistent method undertaking Important Agricultural Land (IAL) for mapping important agricultural lands to Mapping across nine regions in NSW. The Riverina support strategic planning by local and state Murray in southern NSW, as shown in Figure 1, is governments and industry. The booklet “A one of these regions. The IAL Mapping program guideline to identifying important contributes to the NSW Department of Planning agricultural lands in NSW” describes the and Environment’s regional planning actions that method for mapping important agricultural identify the need to map important agricultural lands. lands in NSW. IAL Mapping utilises biophysical, economic and Knowing where important agricultural land is social factors to identify focus industries, define situated and understanding its requirements, industry criteria, and identify production and land use planning considerations. value and contribution will assist state and local government, organisations and industries with making decisions about current and future agricultural land uses. $1.4 billion - the Riverina Murray makes the largest regional contribution to agricultural production in NSW (DPE 2017a). Agricultural output from the Riverina Murray Figure 1: Location of the Riverina Murray IAL Mapping accounts for 12.7% of all agricultural output in region in southern NSW. NSW and continues to be the most important sector for employment within the Riverina (DPE The Riverina Murray region covers approximately 2017a). Agriculture is a vital part of the economy 115,000 square kilometres, or 14% of NSW (DPI and the ongoing growth of the region.