Down So Long

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

TRACKLIST and SONG THEMES 1. Father

TRACKLIST and SONG THEMES 1. Father (Mindful Anthem) 2. Mindful on that Beat (Mindful Dancing) 3. MindfOuuuuul (Mindful Listening) 4. Offa Me (Respond Vs. React) 5. Estoy Presente (JG Lyrics) (Mindful Anthem) 6. (Breathe) In-n-Out (Mindful Breathing) 7. Love4Me (Heartfulness to Self) 8. Mindful Thinker (Mindful Thinking) 9. Hold (Anchor Spot) 10. Don't (Hold It In) (Mindful Emotions) 11. Gave Me Life (Gratitude & Heartfulness) 12. PFC (Brain Science) 13. Emotions Show Up (Jason Lyrics) (Mindful Emotions) 14. Thankful (Mindful Gratitude) 15. Mind Controlla (Non-Judgement) LYRICS: FATHER (Mindful Sits) Aneesa Strings HOOK: (You're the only power) Beautiful Morning, started out with my Mindful Sit Gotta keep it going, all day long and Beautiful Morning, started out with my Mindful Sit Gotta keep it going... I just wanna feel liberated I… I just wanna feel liberated I… If I ever instigated I am sorry Tell me who else here can relate? VERSE 1: If I say something heartful Trying to fill up her bucket and she replies with a put-down She's gon' empty my bucket I try to stay respectful Mindful breaths are so helpful She'll get under your skin if you let her But these mindful skills might help her She might not wanna talk about She might just wanna walk about it She might not even wanna say nothing But she know her body feel something Keep on moving till you feel nothing Remind her what she was angry for These yoga poses help for sure She know just what she want, she wanna wake up… HOOK MINDFUL ON THAT BEAT Coco Peila + Hazel Rose INTRO: Oh my God… Ms. -

CHAPTER 3 Frege 1 Chapter 3 LOT Meets Frege's Problem (Among

CHAPTER 3 Frege Chapter 3 LOT Meets Frege’s Problem (Among Others). Introduction Here are two closely related issues that a theory of intentional mental states and processes might reasonably be expected to address: Frege’s Problem and the Problem of Publicity1. In this chapter, I’d like to convince you of what I sometimes almost believe myself: that an LOT version of RTM has the resources to cope with both of them. I’d like to; but since I’m sure I won’t, I’ll settle for a survey of the relevant geography as viewed from an RTM/LOT perspective. Frege’s Problem If reference is all there is to meaning, then the substitution of coreferring expressions in a linguistic formula should preserve truth. Of course it should: if `Fa’ is true, and if `a’ and `b’ refer to the same, how could `Fb’ not be true too? But it’s notorious that there are cases (what I’ll call `Frege cases’) where the substitution of coreferring expressions doesn’t, preserve truth; it’s old news that John can reasonably wonder whether Cicero is Tully but not whether Tully is; and so forth. It would seem to follow that reference can’t be all there is to meaning. Worse still, it’s common ground (more or less) that synonymous expressions do substitute salve veritate, even in prepositional attitude (PA) contexts.2. So, it seems, that substitution requires something less than synonymy but something more than coreference. Since senses are, practically by 1 A concept is `public’ iff (I) more than one mind can have it and (ii) if one time-slice of a given mind can have it, others can too. -

2 Column Indented

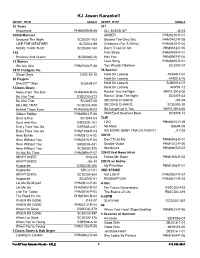

KJ Jason Karaoke!! ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years 311 Wasteland PHM0509-R-09 ALL MIXED UP J5-13 10000 Maniacs AMBER PHM0210-R-01 Because The Night SCDG01-163 Beyond The Grey Sky PHM0402-R-05 LIKE THE WEATHER SCDG03-89 Creatures (For A While) PHM0310-R-04 MORE THAN THIS SCDG03-144 Don't Tread On Me PHM0512-P-05 112 First Straw PHM0409-R-01 Peaches And Cream SGB0065-18 Hey You PHM0907-P-04 12 Stones Love Song PHM0405-R-01 We Are One PHM1008-P-08 You Wouldn't Believe SC3267-07 1910 Fruitgum Co. 38 Special Simon Says DKG-34-15 Hold On Loosely ASK69-1-01 20 Fingers Hold On Loosely AH8015-16 Short D*** Man SC8169-07 Hold On Loosely SGB0016-07 3 Doors Down Hold On Loosely AHP01-12 Away From The Sun PHM0404-R-05 Rockin' Into the Night MKP2 2916-05 Be Like That E3SCDG-373 Rockin' Onto The Night SC8479-03 Be Like That SC3267-08 SECOND CHANCE J91-08 BE LIKE THAT SCDG03-456 SECOND CHANCE SCDG02-30 Behind Those Eyes PHM0506-R-03 So Caught up in You MKP2 2916-06 Citizen Soldier PHM0903-P-08 Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC8479-14 Duck & Run SC3244-03 3LW Duck and Run E4SCDG-161 I DO PHM0210-P-09 Every Time You Go ESP509-4-01 No More G8604-05 Every Time You Go PHM1108-P-03 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) J17-08 Here By Me PHM0512-A-02 3OH!3 Here Without You PHM0310-P-04 Don't Trust Me PHM0903-P-01 Here Without You E6SCDG-431 Double Vision PHM1012-P-05 Here Without You SCDG00-375 StarStrukk PHM0907-P-07 It's Not My Time PHM0806-P-07 3OH!3 feat Neon Hitch KRYPTONITE J108-03 Follow Me Down PHM1006-P-08 KRYPTONITE J36-14 3OH!3 w/ Ke$ha Kryptonite -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

BOB THEIL: Good Morning Everyone. We'll Call the Meeting to Order

The following printout was generated by realtime captioning, an accommodation for the deaf and hard of hearing. This unedited printout is not certified and cannot be used in any legal proceedings as an official transcript. DATE: January 3, 2018 EVENT: Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Meeting >> BOB THEIL: Good morning everyone. We'll call the meeting to order. First we will take attendance. We'll run down the list here. Arsen Ustayev? Barbara Polzer, Blair. Brenda Dare. Denise Curry, Drew Nagele. >> Here. >> Estella Hyde. Fred Hess we have a new member, Heshie Zinman, are you on the phone? Jack Kane? >> MALE SPEAKER: Here. >> BOB THEIL: James Fetzner. >> MALE SPEAKER: Here. >> BOB THEIL: Juanita Gray. Pam is not here. My name is Bob Thiel, I work with her. >> RALPH TRAINER: Hello. >> FRED HESS: That's where we were getting feedback. >> BOB THEIL: Ray Prushnok, Richard Kovalesky. Steven Touzell. Tanya Teglo is on the phone. Terry Brennan. Theo Brady. >> THEO BRADDY: Here. >> BOB THEIL: Veronica Comfort, William White. Okay. Thank you. We'll now review the housekeeping rules. Committee rules as always, please, use professional language, professionalism, point of order, redirect comments through the chairman, wait until called, keep comments to two minutes, we had a lot of problems last meeting we had people didn't get a chance to talk and we want to make sure we kind of keep that tight schedule as possible so we have time at the end for everyone's comments. Meeting minutes the transcripts and the meeting documents are posted on the Listserv at [email protected]. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. Bobby Charles was born Robert Charles Guidry on 21st February 1938 in Abbeville, Louisiana. A native Cajun himself, he recalled that his life “changed for ever” when he re-tuned his parents’ radio set from a local Cajun station to one playing records by Fats Domino. Most successful as a songwriter, he is regarded as one of the founding fathers of swamp pop. His own vocal style was laidback and drawling. His biggest successes were songs other artists covered, such as ‘See You Later Alligator’ by Bill Haley & His Comets; ‘Walking To New Orleans’ by Fats Domino – with whom he recorded a duet of the same song in the 1990s – and ‘(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do’ by Clarence “Frogman” Henry. It allowed him to live off the songwriting royalties for the rest of his life! Two other well-known compositions are ‘The Jealous Kind’, recorded by Joe Cocker, and ‘Tennessee Blues’ which Kris Kristofferson committed to record. Disenchanted with the music business, Bobby disappeared from the music scene in the mid-1960s but returned in 1972 with a self-titled album on the Bearsville label on which he was accompanied by Rick Danko and several other members of the Band and Dr John. Bobby later made a rare live appearance as a guest singer on stage at The Last Waltz, the 1976 farewell concert of the Band, although his contribution was cut from Martin Scorsese’s film of the event. Bobby Charles returned to the studio in later years, recording a European-only album called Clean Water in 1987. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M.