Perspectives on Jim Morrison from the Los

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Doors”—The Doors (1967) Added to the National Registry: 2014 Essay by Richie Unterberger (Guest Post)*

“The Doors”—The Doors (1967) Added to the National Registry: 2014 Essay by Richie Unterberger (guest post)* Original album cover Original label The Doors One of the most explosive debut albums in history, “The Doors” boasted an unprecedented fusion of rock with blues, jazz, and classical music. With their hypnotic blend of Ray Manzarek’s eerie organ, Robby Krieger’s flamenco-flecked guitar runs, and John Densmore’s cool jazz-driven drumming, the band were among the foremost pioneers of California psychedelia. Jim Morrison’s brooding, haunting vocals injected a new strand of literate poetry into rock music, exploring both the majestic highs and the darkest corners of the human experience. The Byrds, Bob Dylan, and other folk-rockers were already bringing more sophisticated lyrics into rock when the Doors formed in Los Angeles in the summer of 1965. Unlike those slightly earlier innovators, however, the Doors were not electrified folkies. Indeed, their backgrounds were so diverse, it’s a miracle they came together in the first place. Chicago native Manzarek, already in his late 20s, was schooled in jazz and blues. Native Angelenos Krieger and Densmore, barely in their 20s, when the band started to generate a local following, had more open ears to jazz and blues than most fledgling rock musicians. The charismatic Morrison, who’d met Manzarek when the pair were studying film at the University of California at Los Angeles, had no professional musical experience. He had a frighteningly resonant voice, however, and his voracious reading of beat literature informed the poetry he’d soon put to music. -

Course Outline and Syllabus the Fab Four and the Stones: How America Surrendered to the Advance Guard of the British Invasion

Course Outline and Syllabus The Fab Four and the Stones: How America surrendered to the advance guard of the British Invasion. This six-week course takes a closer look at the music that inspired these bands, their roots-based influences, and their output of inspired work that was created in the 1960’s. Topics include: The early days, 1960-62: London, Liverpool and Hamburg: Importing rhythm and blues and rockabilly from the States…real rock and roll bands—what a concept! Watch out, world! The heady days of 1963: Don’t look now, but these guys just might be more than great cover bands…and they are becoming very popular…Beatlemania takes off. We can write songs; 1964: the rock and roll band as a creative force. John and Paul, their yin and yang-like personal and musical differences fueling their creative tension, discover that two heads are better than one. The Stones, meanwhile, keep cranking out covers, and plot their conquest of America, one riff at a time. The middle periods, 1965-66: For the boys from Liverpool, waves of brilliant albums that will last forever—every cut a memorable, sing-along winner. While for the Londoners, an artistic breakthrough with their first all--original record. Mick and Keith’s tempestuous relationship pushes away band founder Brian Jones; the Stones are established as a force in the music world. Prisoners of their own success, 1967-68: How their popularity drove them to great heights—and lowered them to awful depths. It’s a long way from three chords and a cloud of dust. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Voices in the Hall: Sam Bush (Part 1) Episode Transcript

VOICES IN THE HALL: SAM BUSH (PART 1) EPISODE TRANSCRIPT PETER COOPER Welcome to Voices in the Hall, presented by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. I’m Peter Cooper. Today’s guest is a pioneer of New-grass music, Sam Bush. SAM BUSH When I first started playing, my dad had these fiddle albums. And I loved to listen to them. And then realized that one of the things I liked about them was the sound of the fiddle and the mandolin playing in unison together. And that’s when it occurred to me that I was trying on the mandolin to note it like a fiddle player notes. Then I discovered Bluegrass and the great players like Bill Monroe of course. You can specifically trace Bluegrass music to the origins. That it was started by Bill Monroe after he and his brother had a duet of mandolin and guitar for so many years, the Monroe Brothers. And then when he started his band, we're just fortunate that he was from the state of Kentucky, the Bluegrass State. And that's why they called them The Bluegrass Boys. And lo and behold we got Bluegrass music out of it. PETER COOPER It’s Voices in the Hall, with Sam Bush. “Callin’ Baton Rouge” – New Grass Revival (Best Of / Capitol) PETER COOPER “Callin’ Baton Rouge," by the New Grass Revival. That song was a prime influence on Garth Brooks, who later recorded it. Now, New Grass Revival’s founding member, Sam Bush, is a mandolin revolutionary whose virtuosity and broad- minded approach to music has changed a bunch of things for the better. -

1. Sitting on Top of the World 9. Miss Kelly Sings the Blues 2. Sunset

1. Sitting on Top of the World 9. Miss Kelly Sings the Blues - Traditional - By Burns/Head 2. Sunset Blues 10. Kind Hearted Woman - By Seaman Dan - By Robert Johnson 3. Your Feets too Big 11. Thieves in the Temple - By Benson/Fisher/Inkspots - By Prince 4. Stormy Weather 12. Midnight Train to Georgia - By Arlen/Koeler - By J Weatherly 5. I can`t Dance (Ive got Ants in my Pants) 13. One O`Clock Jump - By Galnes -Williams - By Count Bassie 6. Singing in the Bathtub 14. Kissing Angels - Composer Unknown - By Geoff Achison 7. Little Red Rooster 15. Mystery Train - By Willie Dixon - By Parker/Phillips 8. Key to the Highway 16. The Sky is Crying - By Big Bill Broonzy - By Elmore James 17. Walking Blues 25. Write me a Few Lines Mississipi - By Robert Johnson - Fred Mc Dowell 18. Bright Lights Big City 26. Moon Going Down - By Jimmy Reed - By Charlie Patton 19. The House of the Rising Sun 27. I`m Going Down - Traditional - By Junior Wells 20. Boom Boom 28. Black Betty - By John Lee Hooker - By Chester Burnett (Howlin` Wolf) 21. Roadrunner 29. Smokestack Lightning - By E. Mc Daniel - By Chester Burnett (Howlin` Wolf) 22. King Bee 30. Whole Lotta Shakin` Goin On - By James Moore ( Slim Harpo) - By Big Joe Williams 23. Sing Sing Sing 31. Hound Dog - By Prima - By J.Leiber and M. Stoller 24. Walking on the Cracks 32. I Can't Stand the Rain - By Dom Turner - By Bryant/Peebles/Miller 33. Aint Nobody here but us Chickens 41. -

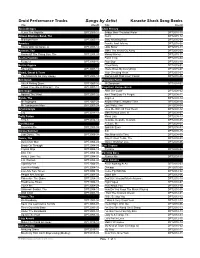

Druid Performance Tracks Karaoke

Druid Performance Tracks Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID Alicia Bridges Elvis Presley I Love The Nightlife DPT2009-14 Bridge Over Troubled Water DPT2015-15 Allman Brothers Band, The Don't DPT2015-12 Midnight Rider DPT2005-11 Early Morning Rain DPT2015-09 America Frankie And Johnny DPT2015-05 Horse With No Name, A DPT2005-12 Little Sister DPT2015-13 Animals, The Make The World Go Away DPT2015-02 House Of The Rising Sun, The DPT2005-05 Money Honey DPT2015-11 Aretha Franklin Patch It Up DPT2015-04 Respect DPT2009-10 Poor Boy DPT2015-10 Bertie Higgins Proud Mary DPT2015-01 Key Largo DPT2007-12 There Goes My Everything DPT2015-07 Blood, Sweat & Tears Your Cheating Heart DPT2015-03 You Made Me So Very Happy DPT2005-13 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' DPT2015-06 Bob Dylan Emmylou Harris Like A Rolling Stone DPT2007-10 Mr Sandman DPT2014-01 Times They Are A-Changin', The DPT2007-11 Engelbert Humperdinck Bob Seger After The Lovin' DPT2008-02 Against The Wind DPT2007-02 Am I That Easy To Forget DPT2008-11 Byrds, The Angeles DPT2008-14 Mr Bojangles DPT2007-09 Another Place, Another Time DPT2008-10 Mr Tambourine Man DPT2007-08 Last Waltz, The DPT2008-04 Crystal Gayle Love Me With All Your Heart DPT2008-12 Cry DPT2014-11 Man Without Love, A DPT2008-07 Dolly Parton Mona Lisa DPT2008-13 9 To 5 DPT2014-13 Quando, Quando, Quando DPT2008-05 Don McLean Release Me DPT2008-01 American Pie DPT2007-05 Spanish Eyes DPT2008-03 Donna Summer Still DPT2008-15 Last Dance, The DPT2009-04 This Moment In Time DPT2008-09 Doors, The Way It Used To Be, The DPT2008-08 Back Door Man DPT2004-02 Winter World Of Love DPT2008-06 Break On Through DPT2004-05 Eric Clapton Crystal Ship DPT2004-12 Cocaine DPT2005-02 End, The DPT2004-06 Fontella Bass Hello, I Love You DPT2004-07 Rescue Me DPT2009-15 L.A. -

Número 112 – Septiembre 2020 CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Página | 1

Número 112 – septiembre 2020 CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Página | 1 Contenido PORTADA Kim Simmonds. Foto (Imagen de su CD: Ain’t Done Directorio Yet) (1) ……………………………………………………………………………………….…. 1 CONTENIDO - DIRECTORIO …..………………………..………..….… 2 Cultura Blues. La Revista Electrónica EDITORIAL ¡Siempre hay otra opción! (2) …………….…………….….. 3 www.culturablues.com PLANETA BLUES Kim Simmonds: Rockin' The Blues (3) ….……. 4 Número 112 – septiembre de 2020 DELMARK RECORDS PRESENTA Par de reyes (2) ……….. 11 LADO B Bob Koester, Delmark Records y el Blues 2 (4) ……………. 14 © Derechos Reservados BLUES A LA CARTA Álbumes en el Salón de la Fama del Director general y editor: Blues (2) ………………………………………………………………………………….….. 19 José Luis García Fernández + COVERS Love in vain (2) ……………..…………………………………….... 27 Subdirector general: José Luis García Vázquez EN VIDEO Come and See About Me (2) ……………………….….….….. 29 Diseño: DE COLECCIÓN Sentir el Blues II (2) ......................................... 30 Aida Castillo Arroyo ESPECIAL DE MEDIANOCHE El disco más raro del Consejo Editorial: mundo – cuento (5) ………………………………………………………………….…. 32 María Luisa Méndez Mario Martínez Valdez CULTURA BLUES DE VISITA Más artistas en Chicago (2) . 35 Octavio Espinosa Cabrera HUELLA AZUL Steelwood Guitars, en el camino de los guitarristas (6) ……………………………………………………………………….….… 40 Colaboradores en este número: DIVÁN EL TERRIBLE Una entrevista sin preguntas. Daniel 1. José Luis García Vázquez Reséndiz. Parte 1 (7) …………………………………………………………………... 43 2. José Luis García Fernández BLA BLE BLI BLO BLUES Let it Blues: Blues Beatles (7) ..... 48 3. Michael Limnios 4. Juan Carlos Oblea The Smoke Wagon 5. Luis Eduardo Alcántara DE FRANK ROSZAK PROMOTIONS Blues Band (2) ………………………………………………….…………………….…… 52 6. María Luisa Méndez 7. Octavio Espinosa DE BLIND RACCOON Wily Bo Walker & Danny Flam (2) …... 53 8. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

Lord Jim Mythos of a Rock Icon Table of Contents

Lord Jim Mythos of a Rock Icon Table of Contents Prologue: So What? pp. 4-6 1) Lord Jim: Prelude pp. 7-8 2) Some Preliminary Definitions pp. 9-10 3) Lord Jim/The Beginning of the Morrison Myth pp. 11-16 4) Morrison as Media Manipulator/Mythmaker pp. 17-21 5) The Morrison Story pp. 18-24 6) The Morrison Mythos pp. 25-26 7) The Mythic Concert pp. 27-29 8) Jim Morrison’s Oedipal Complex pp. 30-36 9) The Rock Star as World Savior pp. 37-39 10) Morrison and Elvis: Rock ‘n’ Roll Mythology pp. 40-44 11) Trickster, Clown (Bozo), and Holy Fool pp. 45-50 12) The Lords of Rock and Euhemerism pp. 51-53 13) The Function of Myth in a Desacralized World: Eliade and Campbell pp. 54- 55 14) This is the End, Beautiful Friend pp. 56-60 15) Appendix A: The Gospel According to James D. Morrison pp. 61-64 15) Appendix B: Remember When We Were in Africa?/ pp. 65-71 The L.A. Woman Phenomenon 16) Appendix C: Paper Proposal pp. 72-73 Prologue: So What? Unfortunately, though I knew this would happen, it seems to me necessary to begin with a few words on why you should take the following seriously at all. An academic paper on rock and roll mythology? Aren’t rock stars all young delinquents, little more evolved than cavemen, who damage many an ear drum as they get paid buckets of money, dying after a few years of this from drug overdoses? What could a serious scholar ever possibly find useful or interesting here? Well, to some extent the stereotype holds true, just as most if not all stereotypes have a grain of truth to them; yet it is my studied belief that usually the rock artists who make the big time are sincere, intelligent, talented, and have a social conscience. -

2017 CATALOGUE for Over Forty Years Omnibus Press Has Been Publishing the Stories That Matter from the Music World

2017 CATALOGUE For over forty years Omnibus Press has been publishing the stories that matter from the music world. Omnibus Press is the World’s/Europe’s largest specialist publisher devoted to music writing, with around thirty new titles a year, with a backlist of over two hundred and seventy titles currently in print and many more as digital downloads. Omnibus Press covers pop, rock, classical, metal, country, psyche, prog, electronic, dance, rap, jazz and many more genres, in a variety of formats. With books that tell stories through graphic art and photography, memoirs and biographies, Omnibus has constantly evolved its list to challenge what a music book can be and this year we are releasing our first talking books. Among Omnibus Press’ earliest acquisitions was Rock Family Trees, by acclaimed music archivist Pete Frame, three editions of which remain in print to this day and have been the basis of two BBC TV series. Over the following decades Omnibus published many best-selling, definitive biographies on some of rock’s greatest superstars. These include Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance by Johnny Rogan, Dear Boy: The Life Of Keith Moon by Tony Fletcher, Uptight: The Velvet Underground Story by Victor Bockris, Catch A Fire: The Life of Bob Marley by Timothy White, Stevie Nicks - Visions, Dreams & Rumours by Zoë Howe, Without Frontiers The Life And Music Of Peter Gabriel by Daryl Easlea and Under The Ivy: The Life & Music of Kate Bush and George Harrison: Behind The Locked Door, both by Graeme Thomson, all of which are regularly cited by magazines and critics as being amongst the finest rock biographies ever published.