Toward a Hip-Hop Theory of Punishment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vision BLACK ARTS + WELLNESS JOURNAL

$FREE .99 tHe VIsiON BLACK ARTS + WELLNESS JOURNAL THE GOLDEN ISSUE T h E G O l D e n I S s u E “She diDn'T reAD boOKs so sHe diDn'T kNow tHat sHe waS tHe woRlD anD tHe heAVenS boILed doWn to a dRop.” - Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God T h E G O l D e n I S s u E leTtER fRom The EdiTOr To be Black is to be divine. To be Black is to be exceptional simply by existing. To breathe while Black is to thrive. To move, and wake up, and allow ourselves the glorious, Godly space to be Black, without fear of retribution or limiting the infinite space we are blessedly entitled to -- is a revolution. There is nothing I love more than seeing us flourish, seeing us beam and shine and glow like the beloved moonlight on water. Yes, we too can be soft. We too create. In fact, the wombs, heartbreak, song, seeds sown by our foremothers birthed this entire nation. While their mouths suckled from our breasts, their whips cracked our back. While we used braiding to design escape routes, they call it KKK boxer braids. They hold vigils for Charleston, and metanoias against White Supremacy, only to have a White woman tell us to praise the police who pushed, shoved, lied, belittled and protected a eugenicist. A Latinx man was expelled for his artistic expression of his resistance to a Klan-run administration that served as an affirmation for those of us who aren't of the caucaus mountains. -

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

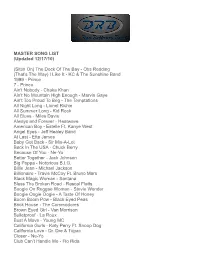

DRB Master Song List

MASTER SONG LIST (Updated 12/17/10) (Sittin On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding (That’s The Way) I Like It - KC & The Sunshine Band 1999 - Prince 7 - Prince Ain't Nobody - Chaka Khan Ain’t No Mountain High Enough - Marvin Gaye Ain’t Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations All Night Long - Lionel Richie All Summer Long - Kid Rock All Blues - Miles Davis Always and Forever - Heatwave American Boy - Estelle Ft. Kanye West Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band At Last - Etta James Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-A-Lot Back In The USA - Chuck Berry Because Of You - Ne-Yo Better Together - Jack Johnson Big Poppa - Notorious B.I.G. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Billionaire - Travie McCoy Ft. Bruno Mars Black Magic Woman - Santana Bless The Broken Road - Rascal Flatts Boogie On Reggae Woman - Stevie Wonder Boogie Oogie Oogie - A Taste Of Honey Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Brick House - The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Bulletproof - La Roux Bust A Move - Young MC California Gurls - Katy Perry Ft. Snoop Dog California Love - Dr. Dre & Tupac Closer - Ne-Yo Club Can’t Handle Me - Flo Rida Cowboy - Kid Rock Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Crazy In Love - Beyonce ft. Jay Z Dancing In The Streets - Martha and The Vendellas Disco Inferno - The Trammps DJ Got Us Falling In Love - Usher Don’t Stop Believing - Journey Don’t Stop The Music - Rihanna Drift Away - Uncle Kracker Dynamite - Taio Cruz Evacuate The Dance Floor - Cascada Everything - Michael Bublé Faithfully - Journey Feelin Alright - Joe Cocker Fight For Your Right - Beastie Boys Fly Away - Lenny Kravitz Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Free Fallin’ - Tom Petty Funkytown - Lipps, Inc. -

Excerpt from Back in the World, a Dramatic Full-Length Produced Play in One Act

1 EXCERPT FROM BACK IN THE WORLD, A DRAMATIC FULL-LENGTH PRODUCED PLAY IN ONE ACT. The play, a series of interconnected monologues delivered by four black veterans of the Vietnam War recall, reflect on and relive some of their searing experiences before, during and after their service in Vietnam. A fifth character—The Man—is a homeless Vietnam Veteran who lives day-to-day in Detroit and fights to maintain his sanity against the backdrop of urban gunfire and the sounds of police helicopters patrolling the skies and sounding (at least to him) like the Huey helicopters he became familiar with in Vietnam. The Man has something in common with the other characters; they may not remember his name but at one point or another, this nameless man has touched the lives of the other characters. Theatrically, he serves as something of a ghost providing “memory dialogue” with the other characters. Anthony “Jam” Brazil is from Indianapolis. He is a veteran of the Fourth Infantry Division: “Duc Pho, May ’69. Saigon, October ’71, December ’71.” He has seen a lot of action and the persistent memory of it hurts. As he states early on in his monologue he has killed about as many people as are in the theater listening to him—some Viet Cong, some Chinese. But it is the innocent casualties he remembers most. Brazil: I killed a seven-year old boy once. Seven or eight. Easiest thing I’ve ever done. Killin’ that boy. Didn’t look back, don’t regret it. I mean, that’s what bein’ a soldier’s all about, right? No frets, no regrets. -

Tom Jennings

12 | VARIANT 30 | WINTER 2007 Rebel Poets Reloaded Tom Jennings On April 4th this year, nationally-syndicated Notes US radio shock-jock Don Imus had a good laugh 1. Despite the plague of reactionary cockroaches crawling trading misogynist racial slurs about the Rutgers from the woodwork in his support – see the detailed University women’s basketball team – par for the account of the affair given by Ishmael Reed, ‘Imus Said Publicly What Many Media Elites Say Privately: How course, perhaps, for such malicious specimens paid Imus’ Media Collaborators Almost Rescued Their Chief’, to foster ratings through prejudicial hatred at the CounterPunch, 24 April, 2007. expense of the powerless and anyone to the left of 2. Not quite explicitly ‘by any means necessary’, though Genghis Khan. This time, though, a massive outcry censorship was obviously a subtext; whereas dealing spearheaded by the lofty liberal guardians of with the material conditions of dispossessed groups public taste left him fired a week later by CBS.1 So whose cultures include such forms of expression was not – as in the regular UK correlations between youth far, so Jade Goody – except that Imus’ whinge that music and crime in misguided but ominous anti-sociality he only parroted the language and attitudes of bandwagons. Adisa Banjoko succinctly highlights the commercial rap music was taken up and validated perspectival chasm between the US civil rights and by all sides of the argument. In a twinkle of the hip-hop generations, dismissing the focus on the use of language in ‘NAACP: Is That All You Got?’ (www.daveyd. -

Angie Stone Mahogany Soul Mp3, Flac, Wma

Angie Stone Mahogany Soul mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Funk / Soul Album: Mahogany Soul Country: US Released: 2001 Style: RnB/Swing, Neo Soul MP3 version RAR size: 1942 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1828 mb WMA version RAR size: 1598 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 604 Other Formats: DMF AIFF VOX RA XM MP3 APE Tracklist Hide Credits Soul Insurance 1 5:01 Written-By – Angie Stone, Eran Tabib Brotha 2 Written-By – Angie Stone, Robert C. Ozuna*, Glenn Standridge, Harold Lilly, Raphael 4:28 Saadiq Pissed Off 3 4:42 Written-By – Angie Stone, Eran Tabib, Rufus Moore, Stephanie Bolton More Than A Woman [Duet W/ Calvin] 4 Featuring – Calvin*Written-By – Balewa Muhammad, Calvin Richardson, Clifton Lighty, 4:54 Eddie Ferrell*, Darren Lighty Snowflakes 5 3:50 Written-By – D. Fekaris*, Jason Hariston, N. Zesses*, Rufus Moore Wish I Didn't Miss You 6 4:31 Written-By – Andrea Martin, Ivan Matias, L. Huff*, G. McFadden, J. Whitehead* Easier Said Than Done 7 3:56 Written-By – Angie Stone, Harold Lilly, John Smith*, Warryn Campbell Bottles & Cans 8 3:54 Written-By – Gerald Isaac The Ingredients Of Love [Duet W/ Musiq Soulchild] 9 Featuring – Musiq Soulchild*Written-By – Angie Stone, C. Haggins*, F. Hubbard*, I. 3:56 Barias*, T. Johnson* What U Dyin' For 10 5:26 Written-By – Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Angie Stone Makings Of You [Interlude] 11 2:30 Written-By – Curtis Mayfield Mad Issues 12 4:49 Written-By – Angie Stone, Eran Tabib, Rufus Moore If It Wasn't 13 4:22 Written-By – Aaron Burns-Lyles*, Angie Stone 20 Dollars 14 4:43 Written-By – Al Green, Gerald Isaac Life Goes On 15 3:57 Written-By – Angie Stone, Eran Tabib, Petey Pablo The Heat [Outro] 16 1:54 Written-By – Angie Stone, Eran Tabib Brotha Part II [Feat. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Black Youth in Urban America Marcyliena Morgan Harvard

“Assert Myself To Eliminate The Hurt”: Black Youth In Urban America Marcyliena Morgan Harvard University (Draft – Please Do Not Quote) Marcyliena Morgan [email protected] Graduate School of Education Human Development & Psychology 404 Larsen Hall 14 Appian Way Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Office:617-496-1809 (617)-264-9307 (FAX) 1 Marcyliena Morgan Harvard University “Assert Myself To Eliminate The Hurt”: Black Youth In Urban America Insert the power cord so my energy will work Pure energy spurts, sporadic, automatic mathematic, melodramatic -- acrobatic Diplomatic, charismatic Even my static, Asiatic Microphone fanatic 'Alone Blown in, in the whirlwind Eye of the storm, make the energy transform and convert, introvert turn extrovert Assert myself to eliminate the hurt If one takes more than a cursory glance at rap music, it is clear that the lyrics from some of hip hop’s most talented writers and performers are much more than the visceral cries of betrayed and discarded youth. The words and rhymes of hip hop identify what has arguably become the one cultural institution that urban youth rely on for honesty (keeping it real) and leadership. In 1996, there were 19 million young people aged 10-14 years old and 18.4 million aged 15-19 years old living in the US (1996 U.S. Census Bureau). According to a national Gallup poll of adolescents aged 13-17 (Bezilla 1993) since 1992, rap music has become the preferred music of youth (26%), followed closely by rock (25%). Though hip hop artists often rap about the range of adolescent confusion, desire and angst, at hip hop’s core is the commitment and vision of youth who are agitated, motivated and willing to confront complex and powerful institutions and practices to improve their 2 world. -

BLOCKHEAD Funeral Balloons

BLOCKHEAD Funeral Balloons KEY SELLING POINTS • Blockhead has released albums with Ninja Tune and produced for artists such as Aesop Rock, Open Mike Eagle and Billy Woods over the course of his nearly two decade long career • Blockhead’s evolution as a producer is on full display, exploring different avenues and sounds with every new release and continuing to forge his own lane between the worlds of hip-hop and electronic music DESCRIPTION ARTIST: Blockhead Funeral Balloons is the new album from acclaimed producer & NYC TITLE: Funeral Balloons fixture Blockhead [real name; Tony Simon]. Funeral Balloons is as bold CATALOG: l-BWZ747 / cd-BWZ747 and irreverent as the title suggests; from the uplifting and energetic mood LABEL: Backwoodz Studioz of “Bad Case of the Sundays” to the spaced out airy grooves found on GENRE: Hip-Hop/Instrumental BARCODE: 616822028315 / 616892517146 “UFMOG” all the way to the 1970s car chase anthem like “Escape from FORMAT: 2XLP / CD NY”, the songs never stop in one place. HOME MARKET: New York RELEASE: 9/8/2017 While, at its core, Funeral Balloons doesn’t stray far from the kind of LIST PRICE: $25.98 / FA / $13.98 / AM music Blockhead has been making since his debut Music by Cavelight, his evolution as a producer is on full display, exploring different avenues TRACKLISTING (Click Tracks In Blue To Preview Audio) and sounds with every new release and continuing to forge his own lane 1. The Chuckles between the worlds of hip-hop and electronic music. 2. Bad case of the Sundays 3. UFOMG 4. Zip It 5. -

Hood, My Street: Ghetto Spaces in American Hip-Hop Music

Pobrane z czasopisma New Horizons in English Studies http://newhorizons.umcs.pl Data: 22/08/2019 20:22:20 New Horizons in English Studies 2/2017 CULTURE & MEDIA • Lidia Kniaź Maria Curie-SkłodowSka univerSity (uMCS) in LubLin [email protected] My City, My ‘Hood, My Street: Ghetto Spaces in American Hip-Hop Music Abstract: As a subculture created by black and Latino men and women in the late 1970s in the United States, hip-hop from the very beginning was closely related to urban environment. Undoubtedly, space has various functions in hip-hop music, among which its potential to express the group identity seems to be of the utmost importance. The goal of this paper is to examine selected rap lyrics which are rooted in the urban landscape: “N.Y. State of Mind” by Nas, “H.O.O.D” by Masta Ace, and “Street Struck,” in order to elaborate on the significance of space in hip-hop music. Interestingly, spaces such as the city as a whole, a neighborhood, and a particular street or even block which are referred to in the rap lyrics mentioned above express oneUMCS and the same broader category of urban environment, thus, words con- nected to urban spaces are often employed interchangeably. Keywords: hip-hop, space, urbanscape. Music has always been deeply rooted in everyday life of African American commu- nities, and from the very beginning it has been connected with certain spaces. If one takes into account slave songs chanted in the fields (often considered the first examples of rapping), or Jazz Era during which most blacks no longer worked on the plantations but in big cities, it seems that music and place were not only inseparable but also nat- urally harmonized. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Sonic Jihadâ•Flmuslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration

FIU Law Review Volume 11 Number 1 Article 15 Fall 2015 Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/lawreview Part of the Other Law Commons Online ISSN: 2643-7759 Recommended Citation SpearIt, Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration, 11 FIU L. Rev. 201 (2015). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.25148/lawrev.11.1.15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Law Review by an authorized editor of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 37792-fiu_11-1 Sheet No. 104 Side A 04/28/2016 10:11:02 12 - SPEARIT_FINAL_4.25.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 4/25/16 9:00 PM Sonic Jihad—Muslim Hip Hop in the Age of Mass Incarceration SpearIt* I. PROLOGUE Sidelines of chairs neatly divide the center field and a large stage stands erect. At its center, there is a stately podium flanked by disciplined men wearing the militaristic suits of the Fruit of Islam, a visible security squad. This is Ford Field, usually known for housing the Detroit Lions football team, but on this occasion it plays host to a different gathering and sentiment. The seats are mostly full, both on the floor and in the stands, but if you look closely, you’ll find that this audience isn’t the standard sporting fare: the men are in smart suits, the women dress equally so, in long white dresses, gloves, and headscarves.