2021-07-04 Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 6-1-2006 SFRA ewN sletter 276 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 276 " (2006). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 91. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #~T. April/llay/June J006 • Editor: Christine Mains Hanaging Editor: Janice M. Boastad Nonfiction Reriews: Ed McKniaht Science Fiction Research Fiction Reriews: Association Philip Snyder SFRA Re~;e", The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068-395X) is published four times a year by the Science Fiction ResearchAs I .. "-HIS ISSUE: sodation (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale; however, starting with issue SFRA Business #256, all issues will be published to SFRA's website no less than 10 weeks Editor's Message 2 after paper publication. For information President's Message 2 about the SFRA and its benefits, see the Executive Meeting Minutes 3 description at the back of this issue. For a membership application, contact SFRA Business Meeting Minutes 4 Treasurer Donald M. Hassler or get one Treasurer's Report 7 from the SFRA website: <www.sfra.org>. -

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 93 (June 2020)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 93, June 2020 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial Announcement for 2021 Editorial: June 2020 FICTION We, the Folk G.V. Anderson Girls Without Their Faces On Laird Barron Dégustation Ashley Deng That Tiny Flutter of the Heart I Used to Call Love Robert Shearman NONFICTION The H Word: Formative Frights Ian McDowell Book Reviews: June 2020 Terence Taylor AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS G.V. Anderson Ashley Deng MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks Support Us on Patreon, or How to Become a Dragonrider or Space Wizard About the Nightmare Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2020 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Grandfailure / Fotolia www.nightmare-magazine.com Editorial Announcement for 2021 John Joseph Adams and Wendy N. Wagner | 976 words We here at Nightmare are very much looking forward to celebrating our 100th issue in January 2021, and we hope you are too; it’s hard to imagine we’ve been publishing the magazine for that long! While that big milestone looms large, that’s got your humble editor thinking about the future. and change—and thinking about how maybe it’s time for some. Don’t worry—Nightmare’s not going anywhere. You’ll still be able to get your weekly and/or monthly scares on the same schedule you’ve come to expect. It’s just that soon yours truly will be passing the editorial torch. Neither is that a reason for worry, because although she will be newly minted in title, the editor has a name and face you already know: Our long-time managing/senior editor, Wendy N. -

ENC 1145 3309 Chalifour

ENC 1145: Writing About Weird Fiction Section: 3309 Time: MWF Period 8 (3:00-3:50 pm) Room: Turlington 2349 Instructor: Spencer Chalifour Email: [email protected] Office: Turlington 4315 Office Hours: W Period 7 and by appointment Course Description: In his essay “Supernatural Horror in Fiction,” H.P. Lovecraft defines the weird tale as having to incorporate “a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.” This course will focus on “weird fiction,” a genre originating in the late 19th century and containing elements of horror, fantasy, science fiction, and the macabre. In our examination of weird authors spanning its history, we will attempt to discover what differentiates weird fiction from similar genres and will use several theoretical and historical lenses to examine questions regarding what constitutes “The Weird.” What was the cultural and historical context for the inception of weird fiction? Why did British weird authors receive greater literary recognition than their American counterparts? Why since the 1980s are we experiencing a resurgence of weird fiction through the New Weird movement, and how do these authors continue the themes of their predecessors into the 21st century? Readings for this class will span from early authors who had a strong influence over later weird writers (like E.T.A. Hoffman and Robert Chambers) to the weird writers of the early 20th century (like Lovecraft, Robert Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Lord Dunsany, and Algernon Blackwood) to New Weird authors (including China Miéville, Thomas Ligotti, and Laird Barron). -

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 77 (February 2019)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 77, February 2019 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial: February 2019 FICTION Quiet the Dead Micah Dean Hicks We Are All Monsters Here Kelley Armstrong 58 Rules to Ensure Your Husband Loves You Forever Rafeeat Aliyu The Glottal Stop Nick Mamatas BOOK EXCERPTS Collision: Stories J.S. Breukelaar NONFICTION The H Word: How The Witch and Get Out Helped Usher in the New Wave of Elevated Horror Richard Thomas Roundtable Interview with Women in Horror Lisa Morton AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Micah Dean Hicks Rafeeat Aliyu MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks Support Us on Patreon or Drip, or How to Become a Dragonrider or Space Wizard About the Nightmare Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2019 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Grandfailure / Fotolia www.nightmare-magazine.com Editorial: February 2019 John Joseph Adams | 153 words Welcome to issue seventy-seven of Nightmare! We’re opening this month with an original short from Micah Dean Hicks, “Quiet the Dead,” the story of a haunted family in a town whose biggest industry is the pig slaughterhouse. Rafeeat Aliyu’s new short story “58 Rules To Ensure Your Husband Loves You Forever” is full of good relationship advice . if you don’t mind feeding your husband human flesh. We’re also sharing reprints by Kelley Armstrong (“We Are All Monsters Here”) and Nick Mamatas (“The Glottal Stop”). Our nonfiction team has put together their usual array of author spotlights, and in the latest installment of “The H Word,” Richard Thomas talks about exciting new trends in horror films. Since it’s Women in Horror Month, Lisa Morton has put together a terrific panel interview with Linda Addison, Joanna Parypinski, Becky Spratford, and Kaaron Warren—a great group of female writers and scholars. -

Edition80720.Pdf

PRAISE FOR JOHN MANTOOTH “John Mantooth writes with enviable grace, vigour, ease. These stories pulsate with the inevitable pain of familial love, and loss, and the horrors of the human condition while remaining peopled with unforgettable characters who move through their lives toward moments of personal realization and doom that can only come from the Southern experience. Mantooth has here collected a group of stories that exceeds the sum of its parts. You won’t regret picking up this collection and will think on these amazing and heartfelt stories long after you’ve closed the covers. Absolutely brilliant.” —John Hornor Jacobs, author of Southern Gods, This Dark Earth, and The Twelve Fingered Boy “The stories in John Mantooth’s powerful debut collection turn a blazing spotlight on those living at—and beyond—society’s margins. In sinuous, elegant prose, Mantooth maps the journeys that have led his characters to dead-ends and disappointments. Mantooth spares his characters nothing, including sufficient self- awareness to understand their roles in their personal catastrophes. These characters grieve their griefs on universal bones, and when they stumble onto hope, it is a small, tough thing that promises no miracles, only the possibility that life tomorrow will be a little better than it was today. This is impressive, assured work, not to be missed.” —John Langan, author of Technicolor and Other Revelations “John Mantooth’s short stories crackle with intelligence and vio- lence. He writes about desperate and simple lives gone not-so-sim- ple, and those lives beat with a savvy and familiar broken heart. -

July 2019 Table of Contents

July 2019 Table of Contents A Not-So-Final Note from the Editor ........................................................................................................... 1 From the Trenches ......................................................................................................................................... 3 HWA Mentor Program Update ..................................................................................................................... 4 The Seers Table! ............................................................................................................................................ 5 HWA Events – Current for 2019 ................................................................................................................. 10 Utah Chapter Update .................................................................................................................................. 11 Pennsylvania Chapter Update ................................................................................................................... 13 San Diego Chapter Update ......................................................................................................................... 16 Wisconsin Chapter Update ......................................................................................................................... 17 LA Chapter Update ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Ohio Chapter Update -

April 2017 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle April 2017 The Next NASFA Meeting Will be the More- or-Less Annual NASFA Cookout/Picnic on 15 April 2017 at Sam & Judy’s House; 2P Concom Meeting 3P at Sue’s House, 22 April 2017 nic/Cookout. It will be at Sue Thorn’s house See the map on d Oyez, Oyez d page 11 for directions. ! In general, future Con†Stellation XXXV Concom Meetings The next NASFA Meeting will be 15 March 2017, but defi- will be at 3P on the same day as the club meeting, at least until nitely NOT at the regular meeting time or location. The NAS- we need to go to two meetings a month. Exceptions for the FA Meeting (and Program and ATMM) will be superseded by concom meeting date/time/place may be made if (for instance) the More-or-Less-Annual NASFA Picnic/Cookout on that date the club does a “field trip” program like we did for the at Judy and Sam Smith’s house. The gathering will start at 2P Huntsville Art Museum in 2016. and last until they kick us out. Bring food and drink to share. FUTURE PROGRAMS Please see the map on page 2 for direction to the Smith’s house. • October: Con†Stellation XXXV Post-Mortem. PLEASE NOTE that beginning in May the regular meeting • December: NASFA Christmas Party. Stay tuned for more location is changing to the new location of the Madison cam- info on the location as we get closer. pus of Willowbrook Baptist Church. See more info, below. JudySue would love to hear from you with ideas for future APRIL PROGRAM AND ATMM programs—even more so if you can lead one yourself! As noted above, all the usual meeting-day events (except the FUTURE ATMMs Concom Meeting) will be subsumed by the More-or-Less-An- We need volunteers to host After-the-Meeting Meetings for nual NASFA Cookout/Picnic. -

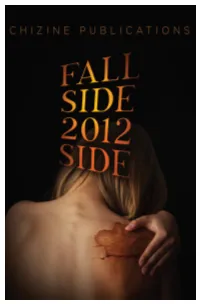

Fall2012catalogue.Pdf

WHAT WHAT ChiZine Publications is willing to take Right now, we’re seeing strong and original risks. We’re looking for the unusual, the genre ideas, but too often they rely on interesting, the thought-provoking. We standard plots, the same settings, and look for writers who are also willing to take two-dimensional characters that serve the risks, who want to take dark genre fiction plot instead of having inner motivation. to a new place, who want to show readers These are “safe” stories—not particularly something they haven’t seen before. CZP challenging, and effortless to consume and W wants to startle, to astound, to share the digest. bliss of good writing with our readership. Because we’re a smaller outfit, we can take E PUBLISH AND What’s Dark Genre Fiction? some risks—find authors and manuscripts that are trying to move the genre forward. We say “dark genre fiction” because too much time is spent fighting over SF vs. Come With Us! horror vs. fantasy. If there’re dragons, it’s fantasy . CZP wants fiction that takes that next step forward. Horror that isn’t just gross or Unless they’re bio-engineered dragons, then going for a cheap scare, but fundamentally it’s SF . disturbing, instilling a sense of true dread. Fantasy that doesn’t necessarily need spells But a dragon apocalypse might be horror . or wizards to create a world far removed from ours, but that imbues the story with We want stories using speculative ele- an otherworldly sense by knocking tropes ments—magic, technology, insanity, gods, on their heads. -

America's Favorite Humorist: David Sedaris a Few of TKE's Favorite

THE 1511 South 1500 East Salt Lake City, UT 84105 InkslingerSummer Issue 2 019 801-484-9100 America’s Favorite Humorist: A Few of TKE’s Favorite Writers’ and David Sedaris Booksellers’ Summer Reads: by Anne Holman Given the taste for summer and the beach that Sedaris’s book gave us, David Sedaris is funny. But more than we asked some other writers who have visited us recently, along with that, he taps into all the stuff every fam- some of our booksellers, what they were looking forward to read- ily has and somehow makes us laugh at ing this summer. Here are their responses—the first from one of our it. In Calypso, his tenth book, Sedaris all-time favorite authors who’s coming to visit us on August 16 to talk tackles two tough topics: his sister Tif- about his new book, Chances Are... which we loved! (see page 22) fany’s suicide and his father’s aging. One response to these issues was to buy a Richard Russo, novelist: I stop what- beach house on the Carolina coast and ever I’m doing when a new Kate Atkin- name it, what else? The Sea Section son novel comes out, but a new Jackson (much to his father’s dismay). In this Brodie novel? After all these years? I series of 21 essays, Sedaris examines his can’t wait. (See Big Sky, page 14) life before (and mostly after) his sister’s Sue Fleming, bookseller: Books I am death, and also life in America from his looking forward to reading include: The and from his father’s viewpoints. -

Penguin Classics

PENGUIN CLASSICS A Complete Annotated Listing www.penguinclassics.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world, providing readers with a library of the best works from around the world, throughout history, and across genres and disciplines. We focus on bringing together the best of the past and the future, using cutting-edge design and production as well as embracing the digital age to create unforgettable editions of treasured literature. Penguin Classics is timeless and trend-setting. Whether you love our signature black- spine series, our Penguin Classics Deluxe Editions, or our eBooks, we bring the writer to the reader in every format available. With this catalog—which provides complete, annotated descriptions of all books currently in our Classics series, as well as those in the Pelican Shakespeare series—we celebrate our entire list and the illustrious history behind it and continue to uphold our established standards of excellence with exciting new releases. From acclaimed new translations of Herodotus and the I Ching to the existential horrors of contemporary master Thomas Ligotti, from a trove of rediscovered fairytales translated for the first time in The Turnip Princess to the ethically ambiguous military exploits of Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions, there are classics here to educate, provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers of all interests and inclinations. We hope this catalog will inspire you to pick up that book you’ve always been meaning to read, or one you may not have heard of before. To receive more information about Penguin Classics or to sign up for a newsletter, please visit our Classics Web site at www.penguinclassics.com. -

Juan Sanmiguel, Tom Reed Members: Deb Canaday

Volume 29 Number 12 Issue 353 May 2017 A WORD FROM THE EDITOR Recon 2017 The Florida Film Festival opened after Easter. There May 4-7 International Palms and Resort were a fair sample of SFF films. Colossal was about an 6515 International Drive alcoholic who has a strange connection to a monster attacking Orlando, FL 32819 Seoul. Birdboy: The Forgotten Children (Psiconautas) was a $15 pre-reg, $25 at the door (HMGS members) Spanish animated film about children looking for a new life in a post apocalyptic world. My Entire High School Sinking Into $25 pre-reg, $35 at the door (non HMGS members) The Sea does a surreal take on high school life using a trippy http://www.hmgs-south.com/ animation style. Albion: The Enchanted Stallion tells the story Gator Con of a young girl who is taken by a mysterious horse to another May 13 world to save a kingdom. This is actress Castile Landon’s first Hilton Airport film and it was a good portal fantasy. 150 Australian Avenue This month is OASIS so we a re get ready for that. West Palm Beach, FL The Nebulas will also be announced during the $7 pre-reg, $10 at the door convention. Some of the short fiction is online. Guests: Chris Doohan (Scotty, Star Trek Continues) Alison McInnis (Pink Ranger, Poer Rangers) Till next time. Mark Sparacio (comic artist) Jose Delbo (comic artist) OASFiS Meeting 4/9/2017 www.gatorcon.net Megacon May 25-28 Officers: Juan Sanmiguel, Tom Reed Members: Deb Canaday, Steve Orange County Convention Center 4-Day-$99 pre-registration , $110 at the door Cole, Arthur Dykeman, Ken Konkol, Dave Ratti, 1-Day (pre)-Thu $20, Fri $35, Sat $45, Sun $35 Patty Russell 1-Day (at the door)-Thu $25, Fri $40, Sat $50, Sun $40 Guests: Stan Morrison (OASIS artist) Guests: Bill Hatfield (OASIS panelist) Stan Lee (comic pioneer) Club Business Gail Simone (comic writer) Juan wanted to thank everyone at the Kevin Smith (film writer-director) picnic, especially griller David Plesic and food Tim Curry (Frank-n-Furter, Rocky Horror) Barry Bostwick (Brad, Rocky Horror) buyer Peggy Stubblefield. -

Crime & Mystery, Horror & Suspense, Sci-Fi & Fantasy

FLAME TREE PUBLISHING NEW TITLES & BACKLIST 2020 FLAME TREE PRESS • Page 3 The Brand New Thriller from FLAME TREE PRESS the Master of FICTION WITHOUT Horror & Suspense FRONTIERS Crime & Mystery, Horror & Suspense, Sci-fi & Fantasy Ramsey Campbell THE WISE FRIEND ‘With influences ranging from the macabre to the First Reviews of The Wise Friend ‘An absolute master of modern horror. And a damn fine writer modern, the novels sprouting forth from this press are at that.’ Guillermo del Toro ‘With razor-sharp prose, Campbell layers his satisfying narrative with intricate, unsettling details to create the feeling of glimpsing something Patrick Torrington’s aunt Thelma was a successful artist whose late work strange out of the corner of one’s eye. Fans of cerebral, slow-burning sure to delight those who love to be thrilled.’ turned towards the occult. While staying with her in his teens he found horror will enjoy this twisty treat.’ evidence that she used to visit magical sites. As an adult he discovers her Publishers Weekly (Starred Review) GEEKS OF DOOM journal of her explorations, and his teenage son Roy becomes fascinated too. His experiences at the sites scare Patrick away from them, but ‘Another towering achievement from one of the genre’s living legends.’ Roy carries on the search, together with his new girlfriend. Can Patrick Booklist (Starred Review) convince his son that his increasingly terrible suspicions are real, or will what they’ve helped to rouse take a new hold on the world? ‘The Wise Friend suggests more than shows. It is a slow-burning horror novel that hints at demonic activity without giving everything away until Ramsey Campbell has been given more awards than any other writer the very end.’ in the field, including theGrand Master Award of the World Horror NY Journal of Books Convention, the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Horror Writers Association, the Living Legend Award of the International Horror Guild About Ramsey Campbell and the World Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award.