Simms As Biographer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

AMERICAN MANHOOD in the CIVIL WAR ERA a Dissertation Submitted

UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael E. DeGruccio _________________________________ Gail Bederman, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana July 2007 UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA Abstract by Michael E. DeGruccio This dissertation is ultimately a story about men trying to tell stories about themselves. The central character driving the narrative is a relatively obscure officer, George W. Cole, who gained modest fame in central New York for leading a regiment of black soldiers under the controversial General Benjamin Butler, and, later, for killing his attorney after returning home from the war. By weaving Cole into overlapping micro-narratives about violence between white officers and black troops, hidden war injuries, the personal struggles of fellow officers, the unbounded ambition of his highest commander, Benjamin Butler, and the melancholy life of his wife Mary Barto Cole, this dissertation fleshes out the essence of the emergent myth of self-made manhood and its relationship to the war era. It also provides connective tissue between the top-down war histories of generals and epic battles and the many social histories about the “common soldier” that have been written consciously to push the historiography away from military brass and Lincoln’s administration. Throughout this dissertation, mediating figures like Cole and those who surrounded him—all of lesser ranks like major, colonel, sergeant, or captain—hem together what has previously seemed like the disconnected experiences of the Union military leaders, and lowly privates in the field, especially African American troops. -

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION of PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School H

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School HONORS Date September 16, 2013 Course No. or level HNRS 270-279 Title HONORS SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES Semester hours 3 Clock hours: Lecture 3 Laboratory 0 Prerequisites Membership in FMU Honors, or permission of Honors Director Enrollment expectation 15 Indicate any course for which this course is a (an) Modification N/A Substitute N/A Alternate N/A Name of person preparing course description: Jon Tuttle Department Chairperson’s /Dean’s Signature _______________________________________ Date of Implementation Fall 2014 Date of School/Department approval: September 13, 2013 Catalog description: 270-279 SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES (3) (Prerequisite: membership in FMU Honors or permission of Honors Director.) Course topics may be interdisciplinary and cover innovative, non-traditional topics within the Behavioral Sciences. May be taken for General Education credit as an Area 4: Humanities/Social Sciences elective. May be applied as elective credit in applicable major with permission of chair or dean. Purpose: 1. For Whom (generally?): FMU Honors students, also others students with permission of instructor and Honors Director 2. What should the course do for the student? HNRS 270-279 will offer FMU Honors members enhanced learning options within the Behavioral Sciences beyond the common undergraduate curriculum and engage potential majors with unique, non-traditional topics. Teaching method/textbook and materials planned: Lecture, -

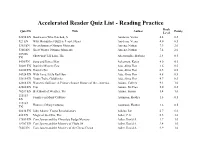

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

The Politics and Culture of Literacy in Georgia, 1800-1920

THE POLITICS AND CULTURE OF LITERACY IN GEORGIA, 1800-1920 Bruce Fort Atlanta, Georgia B. A., Georgetown University, 1985 M.A., University of Virginia, 1989 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia August 1999 © Copyright by Bruce Fort All Rights Reserved August 1999 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the uses and meanings of reading in the nineteenth century American South. In a region where social relations were largely defined by slavery and its aftermath, contests over education were tense, unpredictable, and frequently bloody. Literacy figured centrally in many of the region's major struggles: the relationship between slaveowners and slaves, the competing efforts to create and constrain black freedom following emancipation, and the disfranchisement of black voters at the turn of the century. Education signified piety and propriety, self-culture and self-control, all virtues carefully cultivated and highly prized in nineteenth-century America. Early advocates of public schooling argued that education and citizenship were indissociable, a sentiment that was refined and reshaped over the course of the nineteenth century. The effort to define this relationship, throughout the century a leitmotif of American public life, bubbled to the surface in the South at critical moments: during the early national period, as Americans sought to put the nation's founding principles into motion; during the 1830s, as insurrectionists and abolitionists sought to undermine slavery; during Reconstruction, with the institution of black male citizenship; and at last, during the disfranchisement movement of the 1890s and 1900s, with the imposition of literacy tests. -

The Concept of Statesmanship in John Marshall's Life of George

The Concept of Statesmanship in John Marshall’s Life of George Washington Clyde Ray Brevard College By any conventional measure, Chief Justice John Marshall’s Life of George Washington (1804) was a flop. Intended to be the authoritative bi- ography of the nation’s most celebrated general and president, the work was widely derided at the time of its overdue publication, and since then has been largely forgotten.1 Surely the sense of personal embarrassment Marshall experienced must have been keen, for he admired no public figure more than Washington. Amid his Supreme Court duties, he la- bored for years on the Life, digging deep into American military and po- litical history in hopes of etching in the minds of his fellow citizens the memory of the republic’s foremost founder. Yet in spite of his efforts, on no other occasion were Marshall’s failures more total and public. At one point, Marshall expressed the desire to publish the work anonymously, and one wonders if his wish was motivated less by self-effacement than a faint premonition of the biography’s failure.2 CLYDE RAY is Visiting Instructor of Political Science at Brevard College. 1 C.V. Ridgely’s verdict rings as true today as it did when he reviewed the Life in 1931: “Marshall’s fame as a judge is still growing, but, as a biographer, he has long since been forgotten.” See his “The Life of George Washington, by John Marshall,” Indiana Law Journal 6.4 (1931), 277-288: 287. 2 Marshall wished to remain anonymous from more or less the moment he began writing the Life. -

Poets of the South

Poets of the South F.V.N. Painter Poets of the South Table of Contents Poets of the South......................................................................................................................................................1 F.V.N. Painter................................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................2 CHAPTER I. MINOR POETS OF THE SOUTH.........................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. EDGAR ALLAN POE.........................................................................................................12 CHAPTER III. PAUL HAMILTON HAYNE.............................................................................................18 CHAPTER IV. HENRY TIMROD..............................................................................................................25 CHAPTER V. SIDNEY LANIER...............................................................................................................31 CHAPTER VI. ABRAM J. RYAN..............................................................................................................38 ILLUSTRATIVE SELECTIONS WITH NOTES.......................................................................................45 SELECTION FROM FRANCIS SCOTT KEY...........................................................................................45 -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME CXXXIV July 2010 NO. 3 THE POLITICS OF THE PAGE:BLACK DISFRANCHISEMENT AND THE IMAGE OF THE SAVAGE SLAVE Sarah N. Roth 209 PHILADELPHIA’S LADIES’LIBERIA SCHOOL ASSOCIATION AND THE RISE AND DECLINE OF NORTHERN FEMALE COLONIZATION SUPPORT Karen Fisher Younger 235 “WITH EVERY ACCOMPANIMENT OF RAVAGE AND AGONY”: PITTSBURGH AND THE INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC OF 1918–1919 James Higgins 263 BOOK REVIEWS 287 BOOK REVIEWS FUR, A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters among the Delaware Indians, by Jean R. Soderlund 287 MACMASTER, Scotch-Irish Merchants in Colonial America, by Diane Wenger 288 SPLITTER and WENGERT, eds., The Correspondence of Heinrich Melchior Mühlenberg, vol. 3, 1753–1756, by Marianne S. Wokeck 289 BUCKLEY, ed., The Journal of Elias Hicks, by Emma J. Lapsansky-Werner 291 WOOD, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815, by Peter S. Onuf 292 HALL, A Faithful Account of the Race: African American Historical Writing in Nineteenth-Century America, by Karen N. Salt 293 FLANNERY, The Glass House Boys of Pittsburgh: Law, Technology, and Child Labor, by Richard Oestreicher 295 UEKOETTER, The Age of Smoke: Environmental Policy in Germany and the United States, 1880–1970, by Aaron Cowan 296 TOGYER, For the Love of Murphy’s: The Behind-the-Counter Story of a Great American Retailer, by John H. Hepp IV 298 MADONNA, Pivotal Pennsylvania: Presidential Politics from FDR to the Twenty-First Century, by James W. Hilty 299 COVER ILLUSTRATION: View of Monrovia from a membership certificate for the Pennsylvania Colonization Society, engraved by P. -

Influence of Cavity Availability on Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Group Size

Wilson Bulletin, 110(l), 1998, pp. 93-99 INFLUENCE OF CAVITY AVAILABILITY ON RED-COCKADED WOODPECKER GROUP SIZE N. ROSS CARRIE,,*‘ KENNETH R. MOORE, ’ STEPHANIE A. STEPHENS, ’ AND ERIC L. KEITH ’ ABSTRACT-The availability of cavities can determine whether territories are occupied by Red-cockaded Woodpeckers (Picoides borealis). However, there is no information on whether the number of cavities can influence group size and population stability. We compared group size between 1993 and 1995 in 33 occupied cluster sites that were provisioned with artificial cavities. The number of groups with breeding pairs increased from 22 (67.7%) in 1993 to 28 (93.3%) in 1995. Most breeding males remained in the natural cavities that they had excavated and occupied prior to cavity provisioning in the cluster while breeding females and helpers used artificial cavities extensively. Active cluster sites provisioned with artificial cavities had larger social groups in 1995 (3 = 2.70, SD = 1.42) than in 1993 (3 = 2.00, SD = 0.94; Z = -2.97, P = 0.003). The number of suitable cavities per cluster was positively correlated with the number of birds per cluster (rJ = 0.42, P = 0.016). The number of inserts per cluster was positively correlated with the change in group size between 1993 and 1995 (r, = 0.49, P = 0.004). Our observations indicate that three or four suitable cavities should be maintained uer cluster to stabilize and/or increase Red-cockaded Woodpecker populations. Received 3 March 1997, accepted 57 Oct. 1997. The Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides numbers of old-growth trees for cavity exca- borealis) is an endangered species endemic to vation. -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

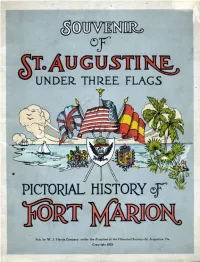

St. Augustine Under Three Flags

SOUVENIR ST.AUGUSTINE UNDER THREE FLAGS PICTORIAL HISTORY OF Pub. by W. J. Harris Company, under the Auspices of the Historical Society—St. Augustine, Fla. Copyright 1925 . PREFACE In this work we have attempted a brief summary of the important events connected with the history of St. Augus- tine and in so doing we must necessarily present the more important facts connected with the history of Fort Marion. The facts and dates contained herein are in accordance with the best authority obtainable. The Historical Society has a large collection of rare maps and books in its Library, one of the best in the State ; the Public Library has also many books on the history of Florida. The City and County records (in English) dating from 1821 contain valuable items of history, as at this date St. Johns County comprised the whole state of Florida east of the Suwannee River and south of Cow's Ford, now the City of Jacksonville. The Spanish records, with a few exceptions, are now in the city of Tallahassee, Department of Agriculture ; the Manuscript Department, Library of Congress, Washington. D. C. and among the "Papeles de Cuba" Seville, Spain. Copies of some very old letters of the Spanish Governors. with English translations, have been obtained by the Historical Society. The Cathedral Archives date from 1594 to the present day. To the late Dr. DeWitt Webb, founder, and until his death, President of the St. Augustine Institute of Science and Historical Society, is due credit for the large number of maps and rare books collected for the Society; the marking and preservation of many historical places ; and for data used in this book. -

One Hundred Nineteenth Commencement

ONE HUNDRED NINETEENTH COMMENCEMENT FRIDAY, MAY 8, 2015 LITTLEJOHN COLISEUM 9:30 A.M. 2:30 P.M. 6:30 P.M. ORDER OF CEREMONIES (Please remain standing for the processional, posting of colors, and invocation.) POSTING OF COLORS Pershing Rifles INVOCATION Sydney J M Nimmons, Student Representative (9:30 A.M. ceremony) Katy Beth Culp, Student Representative (2:30 P.M. ceremony) Corbin Hunter Jenkins, Student Representative (6:30 P.M. ceremony) INTRODUCTION OF TRUSTEES President James P Clements RECOGNITION OF THE DEANS OF THE COLLEGES Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost Robert H Jones CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREE President James P Clements CONFERRING OF DEGREES AND DELIVERY OF DIPLOMAS President James P Clements RECOGNITION AND PRESENTATION OF AWARDS Norris Medal Algernon Sydney Sullivan Awards Alumni Master Teacher Award Faculty Scholarship Award Haleigh Marcolini, Soloist Clemson University Brass Quintet, Instrumentation Dr. Mark A McKnew, University Marshal CEREMONIAL MUSIC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Haleigh Marcolini, Soloist David H Wilkins, Chair .............................Greenville, SC Clemson University Brass Quintet, Instrumentation John N McCarter, Jr., Vice Chair ...............Columbia, SC David E Dukes ............................................Columbia, SC Prelude Leon J Hendrix, Jr. ............................... Kiawah Island, SC Various Marches and Processionals Ronald D Lee .....................................................Aiken, SC Louis B Lynn ...............................................Columbia,