BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

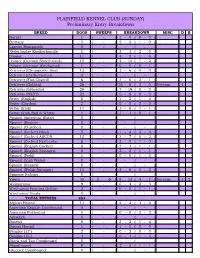

PLAINFIELD KENNEL CLUB (SUNDAY) Preliminary Entry Breakdown

PLAINFIELD KENNEL CLUB (SUNDAY) Preliminary Entry Breakdown BREED DOGS SWEEPS BREAKDOWN MISC D B Barbet 1 ( - ) 1 - 0 ( 0 - 0 ) Brittany 5 ( - ) 2 - 2 ( 1 - 0 ) Lagotto Romagnolo 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Nederlandse Kooikerhondje 5 ( - ) 2 - 1 ( 2 - 0 ) Pointer 11 ( - ) 4 - 2 ( 1 - 4 ) Pointer (German Shorthaired) 15 ( - ) 2 - 10 ( 1 - 2 ) Pointer (German Wirehaired) 1 ( - ) 0 - 0 ( 0 - 1 ) Retriever (Chesapeake Bay) 12 ( - ) 2 - 6 ( 4 - 0 ) Retriever (Curly-Coated) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Retriever (Flat-Coated) 6 ( - ) 3 - 0 ( 2 - 1 ) Retriever (Golden) 26 ( - ) 16 - 6 ( 3 - 0 ) Veteran 1 Retriever (Labrador) 28 ( - ) 7 - 19 ( 0 - 2 ) Retriever (NSDT) 23 ( - ) 5 - 9 ( 9 - 0 ) Setter (English) 8 ( - ) 1 - 2 ( 1 - 4 ) Setter (Gordon) 2 ( - ) 0 - 0 ( 2 - 0 ) Setter (Irish) 14 ( - ) 3 - 6 ( 4 - 1 ) Setter (Irish Red & White) 3 ( - ) 1 - 1 ( 0 - 1 ) Spaniel (American Water) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Boykin) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Clumber) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Cocker) Black 5 ( - ) 1 - 2 ( 2 - 0 ) Spaniel (Cocker) ASCOB 12 ( - ) 3 - 7 ( 0 - 2 ) Spaniel (Cocker) Parti-color 8 ( - ) 2 - 5 ( 1 - 0 ) Spaniel (English Cocker) 8 ( - ) 3 - 3 ( 1 - 1 ) Spaniel (English Springer) 6 ( - ) 2 - 2 ( 1 - 1 ) Spaniel (Field) 1 ( - ) 0 - 0 ( 1 - 0 ) Spaniel (Irish Water) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Sussex) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Welsh Springer) 15 ( - ) 2 - 6 ( 5 - 2 ) Spinone Italiano 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Vizsla 35 ( 5 - 6 ) 8 - 13 ( 4 - 7 ) Veteran 1 2 Weimaraner 9 ( - ) 0 - 4 ( 2 - 3 ) Wirehaired Pointing Griffon 2 ( - ) 0 - 0 ( 1 - 1 ) Wirehaired Vizsla 0 ( - ) - ( - -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Table & Ramp Breeds

Judging Operations Department PO Box 900062 Raleigh, NC 27675-9062 919-816-3570 [email protected] www.akc.org TABLE BREEDS SPORTING NON-SPORTING COCKER SPANIEL ALL AMERICAN ESKIMOS ENGLISH COCKER SPANIEL BICHON FRISE NEDERLANDSE KOOIKERHONDJE BOSTON TERRIER COTON DE TULEAR FRENCH BULLDOG HOUNDS LHASA APSO BASENJI LOWCHEN ALL BEAGLES MINIATURE POODLE PETIT BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN (or Ground) NORWEGIAN LUNDEHUND ALL DACHSHUNDS SCHIPPERKE PORTUGUSE PODENGO PEQUENO SHIBA INU WHIPPET (or Ground or Ramp) TIBETAN SPANIEL TIBETAN TERRIER XOLOITZCUINTLI (Toy and Miniatures) WORKING- NO WORKING BREEDS ON TABLE HERDING CARDIGAN WELSH CORGI TERRIERS MINIATURE AMERICAN SHEPHERD ALL TERRIERS on TABLE, EXCEPT those noted below PEMBROKE WELSH CORGI examined on the GROUND: PULI AIREDALE TERRIER PUMI AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE (or Ramp) PYRENEAN SHEPHERD BULL TERRIER SHETLAND SHEEPDOG IRISH TERRIERS (or Ramp) SWEDISH VALLHUND MINI BULL TERRIER (or Table or Ramp) KERRY BLUE TERRIER (or Ramp) FSS/MISCELLANEOUS BREEDS SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER (or Ramp) DANISH-SWEDISH FARMDOG STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER (or Ramp) LANCASHIRE HEELER MUDI (or Ramp) PERUVIAN INCA ORCHID (Small and Medium) TOY - ALL TOY BREEDS ON TABLE RUSSIAN TOY TEDDY ROOSEVELT TERRIER RAMP OPTIONAL BREEDS At the discretion of the judge through all levels of competition including group and Best in Show judging. AMERICAN WATER SPANIEL STANDARD SCHNAUZERS ENTLEBUCHER MOUNTAIN DOG BOYKIN SPANIEL AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE FINNISH LAPPHUND ENGLISH SPRINGER SPANIEL IRISH TERRIERS ICELANDIC SHEEPDOGS FIELD SPANIEL KERRY BLUE TERRIER NORWEGIAN BUHUND LAGOTTO ROMAGNOLO MINI BULL TERRIER (Ground/Table) POLISH LOWLAND SHEEPDOG NS DUCK TOLLING RETRIEVER SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER SPANISH WATER DOG WELSH SPRINGER SPANIEL STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER MUDI (Misc.) GRAND BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN FINNISH SPITZ NORRBOTTENSPETS (Misc.) WHIPPET (Ground/Table) BREEDS THAT MUST BE JUDGED ON RAMP Applies to all conformation competition associated with AKC conformation dog shows or at any event at which an AKC conformation title may be earned. -

Table & Ramp Breeds

Judging Operations Department PO Box 900062 Raleigh, NC 27675-9062 919-816-3593 [email protected] www.akc.org Table & Ramp Breeds TABLE BREEDS SPORTING TOYS BOYKIN SPANIEL (or Ground or Ramp) ALL TOY BREEDS COCKER SPANIEL ENGLISH COCKER SPANIEL NON-SPORTING ALL AMERICAN ESKIMOS HOUNDS BICHON FRISE BOSTON TERRIER BASENJI COTON DE TULEAR ALL BEAGLES FRENCH BULLDOG ALL DACHSHUNDS LHASA APSO PETIT BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN (or Ground) LOWCHEN PORTUGUSE PODENGO PEQUENO MINIATURE POODLE WHIPPET (or Ground or Ramp) NORWEGIAN LUNDEHUND SCHIPPERKE SHIBA INU WORKING- NO WORKING DOGS ON TABLE TIBETAN SPANIEL TIBETAN TERRIER XOLOITZCUINTLI (Toy and Miniatures) TERRIERS HERDING ALL TERRIERS on TABLE, EXCEPT those noted below: CARDIGAN WELSH CORGI (or Ramp) AIREDALE TERRIER MINIATURE AMERICAN SHEPHERD AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE PEMBROKE WELSH CORGI BULL TERRIER PULI IRISH TERRIERS PYRENEAN SHEPHERD MINI BULL TERRIER (Ground or Table) SHETLAND SHEEPDOG KERRY BLUE TERRIER SWEDISH VALLHUND SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER FSS/MISCELLANEOUS BREEDS AMERICAN HAIRLESS TERRIER PERUVIAN INCA ORCHID (Small and Medium) PUMI RAMP OPTIONAL BREEDS At the discretion of the judge through all levels of competition including group and Best in Show judging. BOYKIN SPANIEL (Ground/Table) CIRNECO DELL’ETNA (7/1/15) STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER CLUMBER SPANIEL WHIPPET (Ground/Table) KEESHONDEN ENGLISH SPRINGER SPANIEL IRISH TERRIERS CARDIGAN WELSH CORGI FIELD SPANIEL KERRY BLUE TERRIER NORWEGIAN BUHUND WELSH SPRINGER SPANIEL SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER POLISH LOWLAND SHEEPDOG NORRBOTTENSPETS (Misc.) BREEDS THAT MUST BE JUDGED ON RAMP Applies to all conformation competition associated with AKC conformation dog shows or at any event at which an AKC conformation title may be earned. -

ALL-BREED DOGSHOW 07.09.2019 Luige Baas, Harjumaa

ALL-BREED DOGSHOW 07.09.2019 Luige baas, Harjumaa ENTRIES: Using EKL online system: https://online.kennelliit.ee/foreign.php (payment by card at the time of entering only, do not make a separate bank payment transfer). To be sent by e-mail: [email protected]. Please send the filled entry form, copy of dogs pedigree and champion/working diplomas (pedigree and champion diploma not necessary for dogs in FI/FIN/ER-registry) and payment copy and. ONLY entries sent to [email protected] will be accepted! Please transfer the entry fees to: Receiver: Põhja-Eesti Koertekasvatajate Klubi, IBAN: EE341010052031990004, SWIFT/BIC: EEUHEE2X. Please write breed and studbook numbers as payment explanation. ENTRY FEES: until 22.07.19 until 19.08.19 from 20.08.19* Baby, puppy, 24 € 39 € veteran Other classes 33 € 43 € 56 € Breeder & 8 € 13 € Progeny Class Brace Competition 13 € 25 € Child & Dog, Junior 13 € 25 € Handler Discount for entries made through EKL Online at https://online.kennelliit.ee/foreign.php (payment by card at the time of entering only) -3€ from the prices mentioned above. Veterans over 10 years free of charge. * Entries during Special Week are only accepted with prior arrangement with club, until it is possible to add dogs to the catalogue. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: entries and inquiries regarding entries: [email protected] for merchants & sales place reservations: [email protected] by phone: +372 517 5958 JUDGES: Group 1. Group 5. All Breeds – Dina Korna, Estonia Alaskan Malamute, Yakutian Laika, Nenets Herding Group 2. Laika, Chukotka Sled Dog, Samoyed, Siberian -

Qualified for Crufts 2019

Qualified for Crufts 2019 at the Benelux Winner Show in Amsterdam 9th August 2018 Breed DogName ChipTattoo Gender Owner Australian Kelpie Yaparoos Arramagong Taz 528140000622424 NHSB 3013958 M Marielle Van Der Heeden Australian Kelpie Didaktic's Omg 978101081715689 FI 39682/17 F Marika Lehtonen Belgian Shepherd Dog, Groenendael Revloch Figo 956000008566119 IKC Z48074 M Jean Lawless Belgian Shepherd Dog, Groenendael Revloch Karma Of Woofhouse 941000017117451 IKC Z84192 F Pamela Mckenzie-Hewitt Belgian Shepherd Dog, Laekenois Ruby Rivers Tristan 968000005743426 VDH SE53174/2011 M Karl Strugalla Belgian Shepherd Dog, Malinois Alcosetha'S Jalco 528140000572448 SE 46836/2014 M Ylva Persson Belgian Shepherd Dog, Malinois Boholdt Gloria Gaynor 208250000102703 DKK 18423/2017 F Annelise Sindalsen Belgian Shepherd Dog, Tervueren Glimbi S El Ninõ V. Ginger 208210000413061 DKK DK07707/2013 M Erik Breukelman Belgian Shepherd Dog, Tervueren Ketunpolun Kiss Me Kate 978101081395539 LSVK BST0051/15 F Marciukaitiene Asta Schipperke Slavjan Al Capone 643094100436648 RKF 3977884 M Maria Spiridonova Schipperke BEACHVIEW'S TIL DEATH DO US PART 1653392 AKC NP33073101 F Lindsey @ Joanne Mclachlan Czechoslovakian Wolfdog My Kayden De La Legende Du Loup Noir 250268500976212 LOF 4004/0 M Regis Haydo Czechoslovakian Wolfdog Arimminum Yasmeen 380260010336510 ROI 15/155486 F Scaglia Laura German Shepherd Dog, double coat Omero Haus Dando 804098100057016 UKU 0182383 M Kholodna Ievgeniia German Shepherd Dog, double coat Adele Da Soc Port 620098100741122 LOP 507637 F -

Breed Categorisations

Breed Categorisations SMALL (UNDER 10KG) Affenpinscher American Hairless Terrier Australian Silky Terrier Australian Terrier Bedlington Terrier Bichon Frise Bolognese Border Terrier Boston Terrier Brussels Griffon (Griffon Bruxellois) Bulldog (Toy) Cairn Terrier Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Cesky Terrier Chihuahua (Long Haired) Chihuahua (Short Haired) Chinese Crested Coton De Tulear Dachshund (Miniature Long-Haired) Dachshund (Miniature Smooth/Short-Haired) Dachshund (Miniature Wire-Haired) Dandie Dinmont Terrier English Toy Terrier (Black & Tan) Fox Terrier (Smooth) Fox Terrier (Wire) French Bulldog Havanese Italian Greyhound Jack Russell Terrier Japanese Chin King Charles Spaniel Lakeland Terrier Lancashire Heeler Lhasa Apso Lowchen (Little Lion Dog) Maltese Manchester Terrier Mexican Hairless Miniature Pinscher Miniature Schnauzer Norfolk Terrier Norwegian Lundehund Norwich Terrier Papillon Parson Russell Terrier Patterdale Terrier Pekinese Pomeranian Poodle (Miniature) Poodle (Toy) Portuguese Podengo Pequeno (Smooth) Portuguese Podengo Pequeno (Wire) Pug Prague Ratter Ratonero Bodeguero Andaluz Schipperke Scottish Terrier Sealyham Terrier Shetland Sheepdog Shih Tzu Skye Terrier Sporting Lucas Terrier Tibetan Spaniel West Highland White Terrier Yorkshire Terrier MEDIUM (10 KG - 20 KG) Alaskan Klee Kai Alpine Dachsbracke American Cocker Spaniel American Water Spaniel Australian Cattle Dog Australian Kelpie Australian Shepherd Basenji Basset Bleu De Gascogne Basset Fauve De Bretagne Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand) Basset Griffon Vendeen -

New Proposed AKC Group from Realignment Committee- Group 10

AKC Group Realignment December, 2011 The American Kennel Club is proposing group realignment and expanding the number of conformation groups from the current 7 to 11. If you would like to read the list of groups and the dogs proposed to go into those groups you can find it at this link: http://www.cspca.com/Realignment/Suggested%20Breed%20List.pdf The Realignment Committee has placed the Chinese Shar-Pei in the Working Spitz group; however we can let AKC know if we had rather be in some other group. Dogs are placed in groups according to common features, traits, skills, natural instincts, ancestry etc. If the Group Realignment passes, then whichever group we end up in will be the group that we will stay in for a long time to come. It is very important that we choose wisely as to what is in the best interest of our breed. It would also be wise to consider what is to be gained by moving from our current group. What do we stand to lose by moving to a new group? We should only move to a new group in order to improve our breed and not for anyone’s personal gain. I have made a photo chart of the different groups that have been proposed by people for our breed. Please study the groups carefully before you vote on the group that you feel would best represent our breed New Proposed AKC Group from Realignment Committee- Group 10: Non-Sporting The breeds in the Non-Sporting Group are a varied collection in terms of size, coat, personality and overall appearance. -

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/As Of: Sept

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/as of: Sept. 2016 A AP Affenpinscher / Monkey Terrier AH Afghanischer Windhund / Afgan Hound AID Atlas Berghund / Atlas Mountain Dog (Aidi) AT Airedale Terrier AK Akita AM Alaskan Malamute DBR Alpenländische Dachsbracke / Alpine Basset Hound AA American Akita ACS American Cocker Spaniel / American Cocker Spaniel AFH Amerikanischer Fuchshund / American Foxhound AST American Staffordshire Terrier AWS Amerikanischer Wasserspaniel / American Water Spaniel AFPV Small French English Hound (Anglo-francais de petite venerie) APPS Appenzeller Sennenhund / Appenzell Mountain Dog ARIE Ariegeois / Arigie Hound ACD Australischer Treibhund / Australian Cattledog KELP Australian Kelpie ASH Australian Shepherd SILT Australian Silky Terrier STCD Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog AUST Australischer Terrier / Australian Terrier AZ Azawakh B BARB Franzosicher Wasserhund / French Water Dog (Barbet) BAR Barsoi / Russian Wolfhound (Borzoi) BAJI Basenji BAN Basst Artesien Normad / Norman Artesien Basset (Basset artesien normand) BBG Blauer Basset der Gascogne / Bue Cascony Basset (Basset bleu de Gascogne) BFB Tawny Brittany Basset (Basset fauve de Bretagne) BASH Basset Hound BGS Bayrischer Gebirgsschweisshund / Bavarian Mountain Hound BG Beagle BH Beagle Harrier BC Bearded Collie BET Bedlington Terrier BBS Weisser Schweizer Schäferhund / White Swiss Shepherd Dog (Berger Blanc Suisse) BBC Beauceron (Berger de Beauce) BBR Briard (Berger de Brie) BPIC Picardieschäferhund / Picardy Shepdog (Berger de Picardie (Berger Picard)) -

Dog Show 101

® ® DOG SHOW 101 ® ® ® ® ® ® “HE’S MY CHAMPION, MY PARTNER, MY HEART. THERE’S ONLY ONE FOOD I TRUST.” KENOBI 2020 Agility National Champion (IDC) 2019 European Open Finalist (Netherlands) 2-Time Team USA Member FUEL THE CHAMPION IN YOUR DOG MARIA BADAMO As a champion agility trainer and a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, Maria Badamo, DVM knows a thing or two about high-performance canine nutrition. And whether she’s preparing her dog, Kenobi, to bring home another title on the agility course or fueling his best in-between events, there’s only OPTIMIZES OXYGEN 30% PROTEIN AND OMEGA-6 one food she trusts — Purina® Pro Plan® Sport Performance 30/20. METABOLISM 20% FAT TO FUEL FATTY ACIDS AND (VO₂ MAX) FOR METABOLIC NEEDS AND VITAMIN A TO INCREASED ENDURANCE MAINTAIN LEAN MUSCLE NOURISH SKIN & COAT SEE WHY CHAMPIONS TRUST PRO PLAN AT PurinaProClub.com/Experts ProPlanSport.com EXCLUSIVELY AT PET SPECIALTY AND ONLINE RETAILERS Maria received coupons from Purina Pro Plan. DOG SHOW 101 BY THE NUMBERS THE WESTMINSTER KENNEL CLUB DOG SHOW COMPETITION STARTS WITH 2500 DOGS ACROSS 209 BREEDS ® ® ALL OF THE AKC-RECOGNIZED BREEDS FALL INTO ONE OF 7 GROUPS: THE WORLD’S GREATEST DOG SHOW For 145 years, dogs from around the world have ventured to New York City to compete for the coveted title of Best In Show at the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show, presented by Purina Pro Plan. For the first time in history, this year’s show will be held at the iconic Lyndhurst Mansion in Tarrytown, NY. Learn more about the dog show, the 209 breeds that will take the ring, and the advanced nutrition of Purina Pro Plan that fuels 95 of the top 100 AKC All Breed Champions.* *Dog News Magazine Top 100 Dogs based on AKC All-Breed Competition and RBIS through 12/31/20. -

Correlation Between Hair Whorls and Different Types Of

Abstract Dogs are very popular pets and it would be useful to find more tools to better understand their behavior. Reactivity can be seen as emotionality, and indicate a heightened state of arousal. So the aim of this study is to investigate the possible links between numbers and directions of hair whorls according to reactivity in dogs, with focus on the dogs’ chest, and upper part of the left and right leg (shoulders). A quantitative research method was used with a questionnaire (containing Negative scale, Positive scale and Questionnaire1 scale of reactivity trait) distributed in two countries; Nor- way and Hungary. To validate the questionnaire a direct observation test was conducted to correlate the owners’ view of the dogs’ behavior to an observers view. Comparing samples from the two countries there was a similar range of male and female dogs, the same range of age, and similar direction of the chest hair whorls, but hair whorls direction and numbers on the legs were different. There was also a difference between coun- tries in the Negative scale and Questionnaire1 scale score and in breed composition. The sev- eral differences between the Hungarian and Norwegian sample can indicate cultural differ- ences, but also that the variation of breeds could have an effect on the results. There was no effect of sex on behavior scale scores in the Norwegian sample or the Hungari- an sample. But there was a weak negative correlation between age and the Positive scale score in the Norwegian sample and a medium negative correlation between age and the scale scores in the Questionnaire1 and Positive scale in the Hungarian sample. -

PREMIUM LISTS SATURDAY May 24, 2016

This is the skeleton Premium for all shows. It has everything except the Show Name, Show Location & Judges. This information will be linked on the show you have selected. PREMIUM LISTS Hosted by, the American Rare Breed Association Example SATURDAY May 24, 2016 The American Rare Breed Association and its sister organization the Kennel Club USA staff do not enter dogs into our conformation dog show events. SHOW HOURS – 7: OO am to 6:00 pm Example Motel 6 840 S. Indian Hill Blvd. Claremont California 91711 NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS SPAYED & NEUTERED CLASSES This is an outdoor venue. You can bring along EZ-Up’s to provide shade for you and your dogs. This show is located on the grounds of the Motel 6, call Steven to make your reservations. He can be reached at 909-621- 4831. Be sure to mention that you are showing your dog with the American Rare Breed Association. This show will be co-hosted by Kennel Club-USA. Kennel Club USA offers conformation shows for both National and International championships. Please call them to register your dog. They can be reached at 301- 868-8284. American Rare Breed Association 9921 Frank Tippett Road Cheltenham, MD 20623 Telephone: 301-868-5718 – Fax: 301-868-6409 http://www.arba.org sales @ arba.org http://www.arba.org/rules_regulations.htm FEES AND AWARDS PRE-ENTRY ENTRY FEES: The following fees are for each dog for each show. Shows 1 thru 6 3 to 6 month dogs, if you are a member……………………………..…………………………….…$20.00 3 to 6 month dogs, Non-Member………………………………………………………………………….$23.00 6 months or older if you are a member…………………………………………………………………$23.00 6 months or older Non-Member………………………………,,………………………………………….$25.00 Your dog can be entered in all of the shows for the event; however the dog cannot be entered into less than 3 shows.