Year of the Snake News No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania the First Question Most People Ask When They See a Snake Is “Is That Snake Poisonous?” Technically, No Snake Is Poisonous

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania The first question most people ask when they see a snake is “Is that snake poisonous?” Technically, no snake is poisonous. A plant or animal that is poisonous is toxic when eaten or absorbed through the skin. A snake’s venom is injected, so snakes are classified as venomous or nonvenomous. In Pennsylvania, we have only three species of venomous snakes. They all belong to the pit viper Nostril family. A snake that is a pit viper has a deep pit on each side of its head that it uses to detect the warmth of nearby prey. This helps the snake locate food, especially when hunting in the darkness of night. These Pit pits can be seen between the eyes and nostrils. In Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Snakes all of our venomous Checklist snakes have slit-like A complete list of Pennsylvania’s pupils that are 21 species of snakes. similar to a cat’s eye. Venomous Nonvenomous Copperhead (venomous) Nonvenomous snakes Eastern Garter Snake have round pupils, like a human eye. Eastern Hognose Snake Eastern Massasauga (venomous) Venomous If you find a shedded snake Eastern Milk Snake skin, look at the scales on the Eastern Rat Snake underside. If they are in a single Eastern Ribbon Snake Eastern Smooth Earth Snake row all the way to the tip of its Eastern Worm Snake tail, it came from a venomous snake. Kirtland’s Snake If the scales split into a double row Mountain Earth Snake at the tail, the shedded skin is from a Northern Black Racer Nonvenomous nonvenomous snake. -

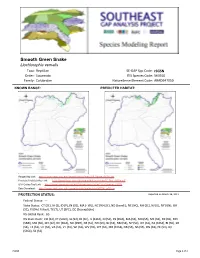

Smooth Green Snake

Smooth Green Snake Liochlorophis vernalis Taxa: Reptilian SE-GAP Spp Code: rSGSN Order: Squamata ITIS Species Code: 563910 Family: Colubridae NatureServe Element Code: ARADB47010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_rSGSN.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_rSGSN.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=rSGSN Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/rSGSN_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: CT (SC), IA (S), ID (P), IN (SE), MA (- WL), NC (W4,SC), ND (Level I), NE (NC), NH (SC), NJ (U), NY (GN), OH (SC), RI (Not Listed), TX (T), UT (SPC), QC (Susceptible) NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: CO (S4), CT (S3S4), IA (S3), ID (SH), IL (S3S4), IN (S2), KS (SNA), MA (S5), MD (S5), ME (S5), MI (S5), MN (SNR), MO (SX), MT (S2), NC (SNA), ND (SNR), NE (S1), NH (S3), NJ (S3), NM (S4), NY (S4), OH (S4), PA (S3S4), RI (S5), SD (S4), TX (S1), UT (S2), VA (S3), VT (S3), WI (S4), WV (S5), WY (S2), MB (S3S4), NB (S5), NS (S5), ON (S4), PE (S3), QC (S3S4), SK (S3) rSGSN Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 17.6 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 1,117.9 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 6,972.8 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 8,108.3 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 US Dept. -

Amphibians & Reptiles

AmphibiansAmphibians && ReptilesReptiles onon thethe NiagaraNiagara EscarpmentEscarpment By Fiona Wagner For anyone fortunate enough to be hiking the Bruce Trail in the early spring, it can be an overwhelming and humbling experience. That’s when the hills awaken to the resounding sound of frogs - the Wood frogs come first, followed by the Spring Peepers and Spiny Softshell Turtle Chrous frogs. By summer, seven more species will have joined this wondrous and sometimes deafening cacophony and like instruments in 15 an orchestra, each one has their unique call. Photo: Don Scallen Bruce Trail Magazine Spring 2010 Photo: Gary Hall Like an oasis in a desert of urban Toronto Zoo. “It’s this sheer diversi- of some of these creatures can be an development, the Niagara ty and the density of some of these astonishing experience, says Don Escarpment is home to more than experiences. I’m hooked for that Scallen, a teacher and vice president 30 reptiles and amphibians, includ- reason. You’ll never know what of Halton North Peel Naturalist ing several at risk species such as the you’re going to find.” Club. Don hits the Trail in early Dusky Salamander and Spotted spring to watch the rare and local Turtle (both endangered) as well as When and where to go Jefferson salamanders and their the threatened Jefferson Salamander. While it’s possible to see amphib- more common relative, the Yellow It is the diversity of the escarpment’s ians and reptiles from March to Spotted salamander. varied habitats, including wetlands, October, you’ll have more success if “A good night for salamander rocky outcrops and towering old you think seasonally, says Johnson. -

Wildlife in Your Young Forest.Pdf

WILDLIFE IN YOUR Young Forest 1 More Wildlife in Your Woods CREATE YOUNG FOREST AND ENJOY THE WILDLIFE IT ATTRACTS WHEN TO EXPECT DIFFERENT ANIMALS his guide presents some of the wildlife you may used to describe this dense, food-rich habitat are thickets, T see using your young forest as it grows following a shrublands, and early successional habitat. timber harvest or other management practice. As development has covered many acres, and as young The following lists focus on areas inhabited by the woodlands have matured to become older forest, the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), a rare amount of young forest available to wildlife has dwindled. native rabbit that lives in parts of New York east of the Having diverse wildlife requires having diverse habitats on Hudson River, and in parts of Connecticut, Rhode Island, the land, including some young forest. Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine. In this region, conservationists and landowners In nature, young forest is created by floods, wildfires, storms, are carrying out projects to create the young forest and and beavers’ dam-building and feeding. To protect lives and shrubland that New England cottontails need to survive. property, we suppress floods, fires, and beaver activities. Such projects also help many other kinds of wildlife that Fortunately, we can use habitat management practices, use the same habitat. such as timber harvests, to mimic natural disturbance events and grow young forest in places where it will do the most Young forest provides abundant food and cover for insects, good. These habitat projects boost the amount of food reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. -

Plymouth Produced in 2012

BioMap2 CONSERVING THE BIODIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS IN A CHANGING WORLD Plymouth Produced in 2012 This report and associated map provide information about important sites for biodiversity conservation in your area. This information is intended for conservation planning, and is not intended for use in state regulations. BioMap2 Conserving the Biodiversity of Massachusetts in a Changing World Table of Contents Introduction What is BioMap2 Ȯ Purpose and applications One plan, two components Understanding Core Habitat and its components Understanding Critical Natural Landscape and its components Understanding Core Habitat and Critical Natural Landscape Summaries Sources of Additional Information Plymouth Overview Core Habitat and Critical Natural Landscape Summaries Elements of BioMap2 Cores Core Habitat Summaries Elements of BioMap2 Critical Natural Landscapes Critical Natural Landscape Summaries Natural Heritage Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, MA 01581 & Endangered phone: 508-389-6360 fax: 508-389-7890 Species Program For more information on rare species and natural communities, please see our fact sheets online at www.mass.gov/nhesp. BioMap2 Conserving the Biodiversity of Massachusetts in a Changing World Introduction The Massachusetts Department of Fish & Game, ɳɧɱɮɴɦɧ ɳɧɤ Dɨɵɨɲɨɮɭ ɮɥ Fɨɲɧɤɱɨɤɲ ɠɭɣ Wɨɫɣɫɨɥɤ˘ɲ Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), and The Nature Cɮɭɲɤɱɵɠɭɢɸ˘ɲ Mɠɲɲɠɢɧɴɲɤɳɳɲ Pɱɮɦɱɠɬ developed BioMap2 ɳɮ ɯɱɮɳɤɢɳ ɳɧɤ ɲɳɠɳɤ˘ɲ biodiversity in the context of climate change. BioMap2 ɢɮɬɡɨɭɤɲ NHESP˘ɲ ȯȬ ɸɤɠɱɲ ɮɥ rigorously documented rare species and natural community data with spatial data identifying wildlife species and habitats that were the focus ɮɥ ɳɧɤ Dɨɵɨɲɨɮɭ ɮɥ Fɨɲɧɤɱɨɤɲ ɠɭɣ Wɨɫɣɫɨɥɤ˘ɲ ȮȬȬȱ State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP). -

CFC Helping Fund Restoration of Smooth Green Snake to Greenway

CFC Citizens for Conservation Saving Living Space for Living Things NEWVol. 36, No. 1, SpringS 2017 CFC helping fund restoration of smooth green snake to Greenway corridor habitat by Tom Vanderpoel The best way to increase biodiversity for all these native species and many more that didn’t make the list is to expand their habitats. Citizens for Conservation (CFC)’s new Barrington Greenway This is what the Barrington Greenway Initiative will do. Join us in Initiative is moving forward on several fronts. our efforts. This will take several generations to accomplish. All along the way meaningful volunteer opportunities will appear. As envisioned, the corridor will wind northward through the In the end, the Barrington area will reap the benefits of weaving Barrington area, from Poplar Creek Forest Preserve south of nature deep into the fabric of our society. I-90 into southeast McHenry County. There are almost 18,000 protected acres in the coalition area. CFC is negotiating a new land purchase we hope to announce shortly which will add to the total. A coalition called the Fox River Hill and Fen Partnership has been created to begin native habitat restoration on a larger scale throughout the Greenway corridor, with a specific focus on wildlife reintroduction, a developing science. Accordingly, the partnership will concentrate on 12 priority species of wildlife identified by Chicago Wilderness as native to our region’s ecosystems. The species include Blanding’s turtle, blue spotted salamander, bobolink, little brown bat, monarch butterfly and red-headed woodpecker. CFC’s support for this project entails monitoring, habitat restoration and actual reintroduction. -

2003 495 Snakes of the United States and Canada

BookReviews117(3).qxd 6/11/04 7:58 PM Page 495 2003 BOOK REVIEWS 495 Snakes of the United States and Canada By Carl H. Ernst and Evelyn M. Ernst. 2003. Smithsonian The maps have surprisingly good detail despite their Books, Washington. xi+668 pages. US$70, CAN$105.00 size which ruled out plotting individual records. The ISBN 1-58834-019-8 subdivisions of ranges into subspecies is not mapped It is over four-and-a-half decades since the publi- but given only in the text. Distributions for the 25 cation of the comprehensive two-volume Handbook of species (three families) which range into Canada are Snakes of United States and Canada by Albert Hazen generally accurate. Exceptions may be the central and Anna Allen Wright (reviewed in The Canadian Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia portions Field-Naturalist 71(4): 201-202 by J. S. Bleakney, for the Western Terrestrial Gartersnake Thamnophis 1957). Those volumes emphasized the need for life elegans (page 385) and the central Alberta and British Thamnophis sirtalis history data and presented the first distribution maps Columbia portions for (page 429) where, following some other recent authors, a disjunct for all species covered (this was a year before the first patchwork is shown. These likely reflect just a lack field guide to amphibians and reptiles in the Peterson of sufficient observations in these areas rather than series appeared). The intervening period has seen not actual range gaps. There is a northernmost disjunct only a proliferation of ecological and behavioural stud- shown for the Northwestern Garter Snake, Thamnophis ies but the compilations of extensive data-bases on dis- ordinoides (page 403), apparently in the vicinity of tribution for virtually every region of North America. -

Newsletter V29-N1

A Note from the Editor…. Happy Spring! If you’re anything like me, the recent warmer temperatures have been very welcome, and a harbinger of herps to come. On a weekend hike recently I was treated to only a toad (probably Fowler’s but couldn’t catch it to be sure) and we saw the tail of some kind of water snake as it fled into the rip rap at the shores of the Potomac River. It was only about 60 F that day, so seeing any snake at all was exciting! Of course, with the warmer weather and herps emerging, our VHS email box for snake identification starts getting busier. It is clear that most people do NOT have any clue about the herpetofauna in their own areas! If you can, do your part to educate your area. Post links to our VHS website on places like NextDoor, Craigslist, and your social media accounts. Remind people to be kind to our scaly friends, and offer to help out neighbors when they have a critter in their yard that they would rather not be there. (If you are able to do that, of course.) The more we educate the public, the less fear they will have. It’s really that simple. I’ve been a professional science educator since 1993, and it’s always my goal to help anyone and everyone learn just a LITTLE BIT MORE than what they already knew. Just one encounter with a knowledgeable person can really open the door for folks to become interested and informed. -

Appendix a Species of Conservation Concern

Appendix A Thomas Barnes/USFWS Bald eagle Species and Habitats of Concern Known, or Potentially Occurring, on Great Bay Refuge and Karner Blue Butterfly Conservation Easement Species & Habitats of Concern Known, or Potentially Occurring, on Great Bay Refuge and Karner Blue Butterfly Conservation Easement Table A.1. Species and Habitats of Concern Known, or Potentially Occurring, on Great Bay Refuge. 9 12 6 8 & 2 3 & 7 1 4 5 10 11 Endangered Species Species Seasons on Refuge Federal Threatened Endangered Species NH State Threatened BCR 30 PIF 9 USFWS Birds of Conservation Concern Fish Federal Trust Data Species Trend Species of Regional Conservation Concern Northern Atlantic Regional Shorebird Plan North American Waterbird Plan North American Waterfowl Plan NH Wildlife Action Plan WATERBIRDS American bittern MMXXHX Great blue heron B, M X King rail MM H Least bittern B, M SC M XHX Pied-billed grebe B, M T X H X Snowy egret MMXH WATERFOWL American black duck B, M,W HH 2C D X Atlantic Population Canada goose B, M HH I Bufflehead MH I Common eider MH D Common goldeneye MM NT Greater scaup MH NT Hooded merganser B, M M I Lesser scaup MH D Mallard BH NT Red-breasted merganser MM I Wood duck B. M M I SHOREBIRDS American woodcock B, M HH 1A 5 X Common snipe MM 3 Common tern B,M T M LX Dunlin MH 3 Greater yellowlegs MH 4 Killdeer B, M M 2 Least sandpiper MM 3 Appendix A. Species and Habitats of Concern Known, or Potentially Occurring, on Great Bay Refuge and A-1 Karner Blue Butterfly Conservation Easement Species & Habitats of Concern Known, or -

Rough Green Snake (Opheodrys Aestivus)

Rough Green Snake (Opheodrys aestivus) Pennsylvania Endangered Reptile State Rank: S1 (critically imperiled) Global Rank: G5 (secure) Identification This is one of two green snakes found in Pennsylvania. Unlike the more widely-distributed smooth green snake, this species has keeled upper body scales and reaches a maximum size of almost 46 inches (26 inches for the smooth green snake). The tail is quite long and tapered relative to the rest of the body. Biology-Natural History Mating takes place in spring, but there are published observations of increased male activity and one mating in September. Females deposit clutches of two to 14 Photo Credit: Robert T. Zappalorti, Nature's Images (usually four to six) elongate soft-shelled eggs, which cling together, during June and July. They are deposited in rotten logs or stumps or natural tree cavities some distance above ground, or cavities beneath moss or flat rocks. More than one female may sometimes deposit eggs in the same place. There is one report that some Florida females may hold eggs over winter and deposit them the following spring. Eggs hatch during late August and September; the 7-inch hatchings are a lighter green than the adults. Caterpillars, grasshoppers, crickets and spiders are primary food items, and are mostly taken from vegetation above ground. When threatened, this snake may react by opening its mouth revealing the dark lining, but very rarely will one bite. North American State/Province Conservation Status Map by NatureServe (August 2007) Habitat State/Province This snake prefers moist habitats such as wet meadows Status Ranks and the borders of lakes, marshes and woodland streams. -

Snakes of New Jersey Brochure

Introduction Throughout history, no other group of animals has undergone and sur- Snakes: Descriptions, Pictures and 4. Corn snake (Elaphe guttata guttata): vived such mass disdain. Today, in spite of the overwhelming common 24”-72”L. The corn snake is a ➣ Wash the bite with soap and water. Snakes have been around for over 100,000,000 years and despite the Range Maps state endangered species found odds, historically, 23 species of snakes existed in New Jersey. However, sense and the biological facts that attest to the snake’s value to our 1. Northern water snake (Nerodia sipedon sipedon): ➣ Immobilize the bitten area and keep it lower than your environment, a good portion of the general public still looks on the in the Pine Barrens of NJ. It heart. most herpetologists believe the non-venomous queen snake is now 22”-53”L. This is one of the most inhabits sandy, forested areas SNAKES OF extirpated (locally extinct) in New Jersey. 22 species of snakes can still snake as something to be feared, destroyed, or at best relegated to common snakes in NJ, inhabit- preferring pine-oak forest with be found in the most densely populated state in the country. Two of our glassed-in cages at zoos. ing freshwater streams, ponds, an understory of low brush. It ➣ lakes, swamps, marshes, and What not to do if bitten by a snake species are venomous, the timber rattlesnake and the northern All snakes can swim, but only the northern water snake and may also be found in hollow queen snake rely heavily on waterbodies. -

SQUAMATA: COLUBRIDAE Opheodrys Aestivus (Linnaeus)

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: COLUBRIDAE Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Walley, H.D. and M.V. Plummer. 2000. Opheodrys aestivus. Opheodrys aestivus (Linnaeus) Rough Green Snake Coluber aestivus Linnaeus 1766:387. Type locality, "Carolina," based on a specimen sent to Linnaeus by Alexander Garden. Holotype unknown. Type locality restricted to Charleston, South Carolina by Smith and Taylor (1950). See Remarks. Leptophis aestivus: Bell 1826:329. Herpetodryas aestivus: Schlegel1837: 15 1. Herpetodryas aesti- vus is a composite name that included not only Herpetodryas Opheodrys aestivus from (Opheodtys) aestivus, but also Philodryas aestivus Dumkril, White County, Arkansas (photograph by M.V.-- Plummer). Bibron, and DumCril 1854, of southern South America. DumCril et al. (1854) separated the two species and, confus. ingly, used the same eipthet to name the South American spe. cies (Kraig Adler, pers. comm.). Leptophis majalis Baird and Girard 1853a: 107. Type locality, "Indianola and New Braunfels, Texas, and Red River." Ho- lotype, National Museum of Natural History (USNM) 1436, female, collected by J.D. Graham, date of collection unknown (not examined by authors). Grobman (1984) restricted the type locality to New Braunfels, Comal County, Texas. See Remarks. Opheodrys aestivus: Cope 1860:560. First use of combination. Cyclophis aestivus: Cope 1875:38. Phyllophilophis aestivus: Garman 1892:283. Phillophilophis aestivus: Hurter 1893:256. Contia aestivus: Boulenger 1894:258. FIGURE 2. Adult 0pheodry.s aestivus from White County, Arkansas Opheodrys aestivas: Gates 1929:555. (photograph by M.V. Plummer). Opheodrys aestivus aestivus: Grobman 1984: 160. Type local- ity, "one mile west of Parkville, McCormick County, South Carolina." Neotype, United States National Museum (USNM) ally I + 2.