The Roots of Indian Foreign Policy Ammar Ali Qureshi January 27, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Servants Being Modi-Fied

CIVIL SERVANTS BEING ‘MODI-FIED’ New Delhi bureaucrats, accustomed to leisurely lunches, swimming & golf in the afternoon and long weekends, have been shaken out of their somnolence, say authors. Fear and suspicion hang heavy over the red-sands. Frequent visitors to Delhi Gymkhana Club, one of the oldest and most coveted clubs of India, cannot stop smiling these days. Once teeming with bureaucrats during, before and after lunch hour, the club is quiet in the afternoons now. "You don't see them throwing their weight around in the bar anymore," chuckles Mohan Guruswamy, the chairman of Delhi-based think-tank Centre for Policy Alternatives and one-time advisor to former finance minister Yashwant Sinha. 1 The scene at India International Centre, another favourite hangout of bureaucrats, is similar. "It's now easier to get a table at IIC during lunch," says Guruswamy, clearly enjoying the development And the driveways of the Delhi Golf Club are deserted during office hours. "People would leave early in the evening to swim or play golf without completing the day's work. All that has changed," says a secretary with a ministry. For the civil servants posted at the Centre, life has seen an upheaval in the three months since Narendra Modi took over as the prime minister. Leisure has shrunk; work production has increased. 2 Officially, central government officers are still on a five-day week schedule, but most of them -- along with their clerks, peons and drivers -- are working almost every Saturday. If they are not clearing files, they're preparing for the week ahead because there is no telling when the Prime Minister's Office will call asking for a file. -

Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal

Vol 5 Issue 12 September 2016 ISSN No : 2249-894X ORIGINAL ARTICLE Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal Review Of Research Journal Chief Editors Ashok Yakkaldevi Ecaterina Patrascu A R Burla College, India Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Kamani Perera Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Lanka Welcome to Review Of Research RNI MAHMUL/2011/38595 ISSN No.2249-894X Review Of Research Journal is a multidisciplinary research journal, published monthly in English, Hindi & Marathi Language. All research papers submitted to the journal will be double - blind peer reviewed referred by members of the editorial Board readers will include investigator in universities, research institutes government and industry with research interest in the general subjects. Regional Editor Manichander Thammishetty Ph.d Research Scholar, Faculty of Education IASE, Osmania University, Hyderabad. Advisory Board Kamani Perera Delia Serbescu Mabel Miao Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania Center for China and Globalization, China Lanka Xiaohua Yang Ruth Wolf Ecaterina Patrascu University of San Francisco, San Francisco University Walla, Israel Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Karina Xavier Jie Hao Fabricio Moraes de AlmeidaFederal Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Sydney, Australia University of Rondonia, Brazil USA Pei-Shan Kao Andrea Anna Maria Constantinovici May Hongmei Gao University of Essex, United Kingdom AL. I. Cuza University, Romania Kennesaw State University, USA Romona Mihaila Marc Fetscherin Loredana Bosca Spiru Haret University, Romania Rollins College, USA Spiru Haret University, Romania Liu Chen Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Ilie Pintea Spiru Haret University, Romania Mahdi Moharrampour Nimita Khanna Govind P. Shinde Islamic Azad University buinzahra Director, Isara Institute of Management, New Bharati Vidyapeeth School of Distance Branch, Qazvin, Iran Delhi Education Center, Navi Mumbai Titus Pop Salve R. -

GP-ORF India's Neighbourhood.Indd

(103'4FSJFT &EJUPST "SZBNBO#IBUOBHBS 3JUJLB1BTTJ NEIGHBOURHOOD FIRST Navigating Ties Under Modi Editors Aryaman Bhatnagar Ritika Passi NEIGHBOURHOOD FIRST Navigating Ties Under Modi Editors Aryaman Bhatnagar Ritika Passi © 2016 by Observer Research Foundation and Global Policy Journal Neighbourhood First: Navigating Ties Under Modi ISBN 978-81-86818-15-2 Inside design: Simi Jaison Designs Cover background image: Rajpath, New Delhi / Adaptor- Plug / Flickr Printed by: Vinset Advertising, Delhi Contents 1 India, India’s Neighbourhood and Modi: Setting the Stage ................................................ 3 2 India’s Neighbourhood Policy through the Decades ............................................................ 14 3 Dealing with Pakistan: India’s Policy Options ..................................................................... 24 4 India’s Afghanistan Policy: Going beyond the ‘Goodwill’ Factor? ...................................... 36 5 India’s Iran Policy in a Changed Dynamic ........................................................................... 46 6 Why Engage in a Neighbourhood Policy? The Theory behind the Act ................................ 56 7 India’s China Policy under Narendra Modi: Continuity and Change ................................... 66 8 Modi’s ‘Act East’ Begins in Myanmar ................................................................................. 76 9 China’s Role in South Asia: An Indian Perspective .............................................................. 86 10 India-Nepal Relations: On -

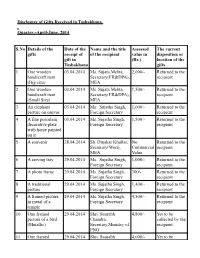

Quarter:-April-June, 2014

Disclosure of Gifts Received in Toshakhana Quarter:-April-June, 2014 S.No Details of the Date of the Name and the title Assessed The current gifts receipt of of the recipient value in disposition or gift in (Rs.) location of the Toshakhana gifts 1 One wooden 03.04.2014 Ms. Sujata Mehta, 2,000/- Returned to the handicraft item Secretary(ER&DPA), recipient (Big size) MEA 2 One wooden 03.04.2014 Ms. Sujata Mehta, 1,500/- Returned to the handicraft item Secretary(ER&DPA), recipient (Small Size) MEA 3 An elephant 03.04.2014 Ms. Sujatha Singh, 1,000/- Returned to the picture on canvas Foreign Secretary recipient 4 A fine porcelain 03.04.2014 Ms. Sujatha Singh, 1,500/- Returned to the decorative plate Foreign Secretary recipient with horse painted on it 5 A souvenir 28.04.2014 Sh. Dinakar Khullar, No Returned to the Secretary(West), Commercial recipient MEA Value 6 A serving tray 29.04.2014 Ms. Sujatha Singh, 1,000/- Returned to the Foreign Secretary recipient 7 A photo frame 29.04.2014 Ms. Sujatha Singh, 300/- Returned to the Foreign Secretary recipient 8 A traditional 29.04.2014 Ms. Sujatha Singh, 1,400/- Returned to the picture Foreign Secretary recipient 9 A framed picture 29.04.2014 Ms. Sujatha Singh, 4,500/- Returned to the in metal of a Foreign Secretary recipient temple 10 One framed 29.04.2014 Shri. Saurabh 4,800/- Yet to be picture of a bird Chandra, collected by the (Metallic) Secretary,Ministry of recipient. PNG 11 One framed 29.04.2014 Shri. -

Regulation 47 of SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015

BIL/SE/2021-22 2nd August, 2021 To, BSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Ltd Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers 5th Floor, Exchange Plaza Dalal Street Bandra Kurla Complex Mumbai – 400 001 Bandra (E), Mumbai 400 051 Scrip Code: 502355 Trading Symbol: BALKRISIND Dear Sir/Madam, Sub: Newspaper Advertisement - Regulation 47 of SEBI (listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 Pursuant to Regulation 47 of the SEBI (listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015, we are enclosing a copy of newspaper advertisement published in the Newspaper of Business Standard and Sakal on 31st July, 2021, towards intimation of fixation of record date i.e Saturday, 14th August, 2021 for the purpose of ascertaining the eligibility of the shareholders for payment of 1st Interim Dividend on equity shares for the financial year 2021-22 to be declared at the Board Meeting of the Company to be held on Friday, the 6th August, 2021, if any. The same has been made available on the Company's Website www.bkt-tires.com Thanking you, Yours faithfully, For Balkrishna Industries Limited Sd/- Vipul Shah Director & Company Secretary DIN: 05199526 Encl: a/a Balkrishna Industries Ltd. CIN No.: L99999MH1961PLC012185 Corporate Office : BKT House, C / 15, Trade World, Kamala Mills Compound, Senapati Bapat Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai - 400 013, India. Tel: +91 22 6666 3800 Fax: +91 22 6666 3898/99 www.bkt-tires.com Registered Office: B-66, Waluj MIDC, Waluj Industrial Area, Aurangabad – 431 136, Maharashtra, India 20 MUMBAI | 31 JULY 2021 . < > BOOK REVIEW N N N An economist’s selective notes Kaushik Basu offers an engaging account of concerns and politely tells him how Though Basu’s tenure at the World Indira Gandhi’s principal secretary, P N Bank was longer than the time he spent his days at North Block and World Bank but Haksar, had “summed it all up when he in the finance ministry, the diary entries wrote that in India, growth and reforms of his North Block days are more detailed steers clear of controversial issues have to be delivered ‘by stealth’”. -

To{'E{{Qrytrmll &.{T-"Rse Roll MINISTRY of FOREIGN AFFAIRS ROYAL Govnnnvtnnt of BHUTAN Gv,U,Vonc Tsnocxnnnc THIMPHU

To{'E{{qryTrmll &.{t-"rSE roll MINISTRY oF FOREIGN AFFAIRS ROYAL GovnnNvTnNT oF BHUTAN Gv,u,voNc TsnocxnnNc THIMPHU MFA/BDA -1t1o1t * lLl Press Release At the invitation of the Prime Minister of lndia Dr. Manmohan Singh, Lyonchhen Tshering Tobgay will be on an officiat visit to lnclia from 30th August to 4th September, 2013. Lyonchhen Tshering Tobgay will be accompanied by his spouse Aum Tashi Doma, Lyonpo Rinzin Dorji, Foreign Minister and other senior officials of the Royal Government. During the visit, Lyonchhen will call on the President of lndia H.E. Mr. Pranab Mukherjee, and the Vice President of lndia H.E. Mr. Mohammad Hamid Ansari. Lyonchhen will also meet the Prime Minister of !ndia H.E. Dr. Manmohan Singh, Foreign Minister H.E. Mr. Salman Khurshid, Finance Minister H.E. Mr. P. Chidambaram, National Security Adviser H.E. Mr. Shivshankar Menon, Foreign Secretary H.E. Mrs. Sujatha Singh and other senior officials of the Government of lndia. During the meetings with the lndian leaders, Lyonchhen wil! be discussing issues of mutual bilateral interests as well as Government of lndia's assistance to Bhutan's 11th Ptan. Lyonchhen will also travel to Hyderabad to visit lT Parks in Hitech City. While in Hyderabad Lyonchhen wi!! meet the Governor of Andhra Pradesh H.E. Mr. ESL Narasimhan. Regular exchange of high-level visits between Bhutan and lndia is a well- established tradition which plays a vital role in nurturing lndo-Bhutan relationS. Lyonchhen's visit will further strengthen the close ties of friendship and understanding between the two countries. -

402, India's Neighbourhood

Directorate of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU JAMMU STUDY MATERIAL M.A. POLITICAL SCIENCE SEMESTER IV COURSE NO. POL - 402 INDIA’S NEIGHBOURHOOD, EXTENDED NEIGHBOURHOOD AND NEAR ABROAD Prof. Baljit Singh Dr. Mamta Sharma Course Coordinator Teacher In-Charge HOD, Deptt. of Political Science, P.G. Political Science, University of Jammu. DDE, University of Jammu. All copyright privileges of the material are reserved by the Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, JAMMU-180 006 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, MA Political Science, Semester IV, India’s Neighbourhood 1 INDIA’S NEIGHBOURHOOD, EXTENDED NEIGHBOURHOOD AND NEAR ABROAD Course Editor : Course Contributors : Dr. V.V. Nagendra Rao Dr. Baljit Singh Dr. V.V. Nagendra Rao Dr. Rajnesh Saryal Dr. Suneel Kumar © Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, 2021 * All rights reserved. No Part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the DDE, University of Jammu. * The Script writer shall be responsible for the lesson / script submitted to the DDE and any plagiarism shall be his/her entire responsibility. Printed by : J&K Revolution Printers / 2021 / 700 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, MA Political Science, Semester IV, India’s Neighbourhood 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Writer Page UNIT INDIA, SOUTH ASIA AND CHINA I 1.1 India’s Neighbourhood Policy : Continuity and Change Baljit Singh 2 1.2 India’s Policy towards Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan Baljit Singh 19 1.3 India’s Policy towards, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bhutan Baljit Singh 53 1.4 China in South Asia and Its implications for India Baljit Singh 80 UNIT INDIA, SOUTH EAST ASIA AND FAR EAST II 2.1 India’s Policy towards South East Asia: V. -

GP-ORF India's Neighbourhood.Indd

(103'4FSJFT &EJUPST "SZBNBO#IBUOBHBS 3JUJLB1BTTJ NEIGHBOURHOOD FIRST Navigating Ties Under Modi Editors Aryaman Bhatnagar Ritika Passi NEIGHBOURHOOD FIRST Navigating Ties Under Modi Editors Aryaman Bhatnagar Ritika Passi © 2016 by Observer Research Foundation and Global Policy Journal Neighbourhood First: Navigating Ties Under Modi ISBN 978-81-86818-15-2 Inside design: Simi Jaison Designs Cover background image: Rajpath, New Delhi / Adaptor- Plug / Flickr Printed by: Vinset Advertising, Delhi Contents 1 India, India’s Neighbourhood and Modi: Setting the Stage ................................................ 3 2 India’s Neighbourhood Policy through the Decades ............................................................ 14 3 Dealing with Pakistan: India’s Policy Options ..................................................................... 24 4 India’s Afghanistan Policy: Going beyond the ‘Goodwill’ Factor? ...................................... 36 5 India’s Iran Policy in a Changed Dynamic ........................................................................... 46 6 Why Engage in a Neighbourhood Policy? The Theory behind the Act ................................ 56 7 India’s China Policy under Narendra Modi: Continuity and Change ................................... 66 8 Modi’s ‘Act East’ Begins in Myanmar ................................................................................. 76 9 China’s Role in South Asia: An Indian Perspective .............................................................. 86 10 India-Nepal Relations: On -

Diplomacy-At-The-Cutting-Edge.Pdf

By the Same Author Inside Diplomacy (2000 & 2002) Managing Corporate Culture: Leveraging Diversity to give India a Global Competitive Edge (co-author, 2000) Bilateral Diplomacy (2002) The 21st Century Ambassador: Plenipotentiary to Chief Executive (2004) Asian Diplomacy: The Foreign Ministries of China, India, Japan, Singapore and Thailand (2007) Foreign Ministries: Managing Diplomatic Networks and Delivering Value (co-editor, 2007) Diplomacy for the 21st Century: A Practitioner Guide (2011) Economic Diplomacy: India’s Experience (co-editor, 2011) India’s North-East States, the BCIM Forum and Regional Integration (co-author, 2012) The Contemporary Embassy: Paths to Diplomatic Excellence (2013) Kishan S. Rana, IFS (Retd) Former Indian Ambassador to Germany (Publishers, Distributors, Importers & Exporters) 4402/5-A, Ansari Road (Opp. HDFC Bank) Darya Ganj, New Delhi-110 002 (India) Off. 23260783, 23265523, Res. 23842660 Fax: 011-23272766 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Website: www.manaspublications.in © Kishan S. Rana, 2016 ISBN 978-81-7049-511-6 ` 595.00 All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior written consent, in any form of binding, soft cover or e-version, etc. except by the authorized companies and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser and without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electrical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher of the book. -

India-Germany Relations Germany Is India's

India-Germany Relations Germany is India’s largest trading partner in Europe and 2nd most importantpartnerintermsoftechnologicalcollaborations. Germany has been the 8th largest foreign direct investor in India since 1991. During April-July 2013, German FDI has been around US$ 518 mn, which made it the 4th largest foreign direct investor during the period. Political Relations India was one of the first countries to end the state of war with post-war Germany in 1951 and amongst the first countries to grant recognition to Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). The relationship, based on common values of democracy and rule of law has gained significantly in strength in the 1990s following India’s economic liberalization and the end of Cold War. Germany and India cooperate closely on the issue of UNSC expansion within the framework of G-4. India and Germany have a ‘strategic partnership’ since 2001, which has been further strengthened with the first Intergovernmental Consultations (IGC) held in New Delhi in May 2011. The two countries have several institutionalized arrangements to discuss bilateral and global issues of interest viz. Strategic Dialogue, Foreign Office Consultations, Joint Commission on Industrial and Economic Cooperation, Defence Committee Dialogue and Joint Working Group on Counter- Terrorism. The course of the future relationship was set by the two visits of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to Germany in 1956 and 1960. There are regular bilateral exchanges, including at the highest level. Prime Minister Shri Manmohan Singh has visited Germany four times in the last few years. He visited Hannover and Berlin in April, 2006. He again visited Berlin in June 2007 to participate in the G8 Summit with five outreach countries. -

The Democracy Support Deficit: Despite Progress, Major Countries Fall Short Daniel Calingaert, Arch Puddington, and Sarah Repucci

Supporting Democracy Abroad: An Assessment of Leading Powers minimal moderate moderate moderate limited limited minimal strong minimal very strong moderate Brazil | European Union | France | Germany | India | Indonesia | Japan | Poland | South Africa | Sweden | United States support for democracy and human rights The Democracy Support Deficit: Despite Progress, Major Countries Fall Short Daniel Calingaert, Arch Puddington, and Sarah Repucci EXECUTIVE SUMMARY and human rights through their trade poli- The world’s leading democracies are making cies and in their responses to coups. significant efforts to promote democracy In relations with China, immediate eco- and human rights, but their policies are nomic and strategic interests almost always inconsistent, and they often overlook au- override support for democracy and human thoritarian threats. As authoritarian states rights. Virtually none of the democracies collaborate to push back against political under review have been willing to confront and human rights around the globe, democ- Beijing directly or consistently, despite the racies must reassess their approach and regime’s pattern of abuses. adopt a bolder and more coherent strategy. The study also found that although About this project Among the 11 regional and global pow- support for democracy through regional This project analyzes ers examined in this study, the democracies or international bodies can aid legitimacy, support by 11 democratic in Latin America, Africa, and Asia were less these organizations are rarely effective powers for democracy and human rights likely to exert pressure on rights violators in without the leadership of a major country. during the period their regions and less inclined to condemn Indeed, democratic powers sometimes use June 2012–May 2014. -

October Title 2014.Cdr

VOL. XXVI No. 10 October 2014 Rs. 20.00 The Site of APEC China 2014 Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Le Yucheng met with Mr. Le Yucheng, Chinese Ambassador to India shook Indian Foreign Secretary Ms. Sujatha Singh in the hands with Mr. Vijay Kumar Singh, Minister of State for th Embassy on Oct. 13, 2014. External Affairs at the Reception of the 65 Anniversary of People's Republic of China on Sept. 24, 2014. Mr. Le Yucheng, Chinese Ambassador to India, met with On Sept. 29, 2014 Chinese Ambassador Mr. Le Yucheng Mr. Anil Wadhwa, Secretary (East) of Indian Ministry of attended the celebration hosted by the India-China External Affairs in New Delhi on Sept. 26, 2014. Both Society in New Delhi to mark the 65th anniversary of the sides exchanged views on how to strengthen bilateral founding of the People's Republic of China. More than a relations between China and India. hundred friendly personages from all walks of life attended the event. A monk from Shaolin Temple of China's Henan Province China National Tourist Office (CNTO)-New Delhi won the was teaching Indian children Kungfu at a special the Award of Best Marketing Destination at the event of CHINESE KUNGFU SHOW held by Chinese Embassy and 10th Hospitality India & Explore the World Annual the India China Economic and Cultural Council in New International Awards held on Oct.10, 2014 in New Delhi. Delhi on Sept.23, 2014 . 2014 APEC The 2014 APEC Economic Leaders’ Week Wang Yi and Commerce Minister Gao will coincide with the 25th anniversary of Hucheng, and including Foreign Affairs and APEC’s founding to boost trade and economic Trade Ministers from the other 20 APEC cooperation across the Pacific and bring economies, the meeting will decide the together the Leaders, Ministers and Senior contours of joint policy development and Officials of the 21 APEC member economies implementation moving forward.