Shake It up Şekerim Turkey’S Eurovision Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies. Vol. 3. No. 1. 2002

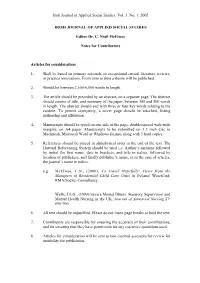

Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies. Vol. 3. No. 1. 2002 IRISH JOURNAL OF APPLIED SOCIAL STUDIES Editor Dr. C. Niall McElwee Notes for Contributors Articles for consideration: 1. Shall be based on primary research, or exceptional critical literature reviews, or practice innovations. From time to time a theme will be published. 2. Should be between 2,500-6,000 words in length. 3. The article should be preceded by an abstract, on a separate page. The abstract should consist of title, and summary of the paper, between 300 and 500 words in length. The abstract should end with three or four key words relating to the content. To permit anonymity, a cover page should be attached, listing authorship and affiliation. 4. Manuscripts should be typed on one side of the page, double-spaced with wide margins, on A4 paper. Manuscripts to be submitted on 3.5 inch disc in Macintosh, Microsoft Word or Windows format, along with 3 hard copies. 5. References should be placed in alphabetical order at the end of the text. The Harvard Referencing System should be used i.e. Author’s surname followed by initial for first name, date in brackets, and title in italics, followed by location of publishers, and finally publisher’s name; or in the case of articles, the journal’s name in italics. e.g. McElwee, C.N., (2000), To Travel Hopefully: Views from the Managers of Residential Child Care Units in Ireland. Waterford: RMA/SocSci Consultancy. Wells, J.S.G., (1998) Severe Mental Illness. Statutory Supervision and Mental Health Nursing in the UK, Journal of Advanced Nursing 27: 698-706. -

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

Acting the Nation

Acting the Nation Women on the Stage and in the Audience of Theatre in the Late Ottoman Empire and Early Turkish Republic Cora Skylstad TYR 4590 – Master’s thesis in Turkish Studies Area Studies of Asia, the Middle East and Africa Department of Cultural Studies and Oriental Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO October 2010 ii iii Abstract In the first decades of the 20th century, the public position of actresses underwent a radical transformation in Turkey. While the acting profession had long been commonly regarded as unsuitable for Muslim women and had been monopolized by women belonging to the non- Muslim minorities, in the 1920s the Muslim actress was not only legitimized but in fact embraced by the state as a model for Turkish women. In the works of Turkish and Ottoman theatre history, the emergence of Muslim actresses has been given some attention, but it has not been studied from a critical perspective inspired by theoretical questions. Moreover, the process of legitimization of Muslim women as theatre audience, which took place prior to the legitimization of the actresses, has been ignored. The present thesis seeks to develop a better understanding of these developments by approaching them as part of social and political history, while drawing inspiration from an interdisciplinary field of scholarship on gender and theatre. The time period studied begins with the late era of the Ottoman Empire and ends with the early years of the Turkish Republic, covering a time span of more than fifty years. In order to capture the complexities of the subject, a wide array of written sources, including memoirs, interviews, theatre reviews, books and a theatre play, are included in the analysis. -

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising Awards • AFI Awards • AICE & AICP (US) • Akil Koci Prize • American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Music • American Cinema Editors • Angers Premier Plans • Annie Awards • APAs Awards • Argentine Academy of Cinematography Arts and Sciences Awards • ARIA Music Awards (Australian Recording Industry Association) Ariel • Art Directors Guild Awards • Arthur C. Clarke Award • Artios Awards • ASCAP awards (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) • Asia Pacific Screen Awards • ASTRA Awards • Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTS) • Australian Production Design Guild • Awit Awards (Philippine Association of the Record Industry) • BAA British Arrow Awards (British Advertising Awards) • Berlin International Film Festival • BET Awards (Black Entertainment Television, United States) • BFI London Film Festival • Bodil Awards • Brit Awards • British Composer Awards – For excellence in classical and jazz music • Brooklyn International Film Festival • Busan International Film Festival • Cairo International Film Festival • Canadian Screen Awards • Cannes International Film Festival / Festival de Cannes • Cannes Lions Awards • Chicago International Film Festival • Ciclope Awards • Cinedays – Skopje International Film Festival (European First and Second Films) • Cinema Audio Society Awards Cinema Jove International Film Festival • CinemaCon’s International • Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards – An annual awards program bestowed by Classic Rock Clio -

The Eurovision Song Contest. Is Voting Political Or Cultural? ☆ ⁎ Victor Ginsburgh A, Abdul G

Author's personal copy Available online at www.sciencedirect.com European Journal of Political Economy 24 (2008) 41–52 www.elsevier.com/locate/ejpe The Eurovision Song Contest. Is voting political or cultural? ☆ ⁎ Victor Ginsburgh a, Abdul G. Noury b, a ECARES, Université Libre de Bruxelles and Center for Operations Research and Econometrics, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium b ECARES, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium Received 19 December 2005; received in revised form 18 May 2007; accepted 21 May 2007 Available online 2 June 2007 Abstract We analyze the voting behavior and ratings of judges in a popular song contest held every year in Europe since 1956. The dataset makes it possible to analyze the determinants of success, and gives a rare opportunity to run a direct test of vote trading. Though the votes cast may appear as resulting from such trading, we show that they are rather driven by quality of the participants as well as by linguistic and cultural proximities between singers and voting countries. Therefore, and contrary to what was recently suggested, there seems to be no reason to take the result of the Contest as mimicking the political conflicts (and friendships). © 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. JEL classification: D72; Z10 Keywords: Voter trading; Voting behavior; Popular music; Contests 1. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to analyze the determinants of success and voting behavior of judges in one of the most popular singing contest held since 1956 in Europe, the Eurovision Song Contest. The competition is interesting since each country (player) votes for singers (or groups of singers) of all other participating countries. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abdulhadi, Rabab. (2010). ‘Sexualities and the Social Order in Arab and Muslim Communities.’ Islam and Homosexuality. Ed. Samar Habib. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 463–487. Abercrombie, Nicholas, and Brian Longhurst. (1998). Audiences: A Sociological Theory of Performance and Imagination. London: Sage. Abu-Lughod, Lila. (2002). ’Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropolog- ical Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others.’ American Anthropologist 104.3: 783–790. Adams, William Lee. (2010). ‘Jane Fonda, Warrior Princess.’ Time, 25 May, accessed 15 August 2012. http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/ 0,28804,1990719_1990722_1990734,00.html. Addison, Paul. (2010). No Turning Back. The Peacetime Revolutions of Post-War Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Ahmed, Sara. (2004). The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Ahmed, Sara. (2010a). The Promise of Happiness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Ahmed, Sara. (2010b). ‘Killing Joy: Feminism and the History of Happiness.’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35.3: 571–594. Ahmed, Sara. (2011). ‘Problematic Proximities: Or Why Critiques of Gay Imperi- alism Matter.’ Feminist Legal Studies 19.2: 119–132. Alieva, Leila. (2006). ‘Azerbaijan’s Frustrating Elections.’ Journal of Democracy 17.2: 147–160. Alieva, Leila. (2009). ‘EU Policies and Sub-Regional Multilateralism in the Caspian Region.’ The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs 44.3: 43–58. Allatson, Paul. (2007). ‘ “Antes cursi que sencilla”: Eurovision Song Contests and the Kitsch-Drive to Euro-Unity.’ Culture, Theory & Critique 48: 1: 87–98. Alyosha. (2010). ‘Sweet People’, online video, accessed 15 April 2012. http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=NT9GFoRbnfc. -

= Mühim Bir Hadise

Şimdiye kadar memleket İspanyada grevin muvaffak haricine milyonlarca döviz ka olmadığı anlaşılıyor. Dün çır an bir şebeke efradı yakayı Madritte sadece iki gazete ele verdi. neşredildi. :Sahip ve Batmuharriri : Siirt Meb'uııu MAHMUT Tel. { P.1üdür: 24318. Yazı itleri müdürü: 24319. 9 uncu sene No. 2907 ÇARŞAMBA 14 MART 1934 • Jdare •• Matbaa : 24310. Silah yarışı • • • Bir hırMtan clnletfer aa ı ımda silalı Başvekil ilk e r mes,,.. esını çıkç a t "''·-me müzııkereleri devam ederken, ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~·-.-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- diğer tarak.on da sililılanma yanıı bat· la.iuı görünüyor. lngiltere, Fransa ve Amerika, 1934 aenesi zarfıoda "milli bıÜdafaa" namı a1tmda ordu, donanma ''Meseleyi cesaretle, hakikati olduğu gibi görerek \re hava kuvvetleri için ayırdııldarı tah•İ aatı Millet Mecliılerine tevdi etmişleT· dir. mütalea etmek ve memlekete bildirmek vazifemizdir,, Tllhıisıı.tlann her rııkamında bir lazlalık 6lduğu iddia edilebilir. Bilhuaa donan· ..... ve hava kuvvetleri için ayrılan tah· f"aatlardaki fazlalık nazarı dikkati cel· ı111111111111111111111111111uıııııııııııı11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111uıııııııııııııııııııııımııııuıııııııııııııııııııııııııı~ ı· Ik d . h kk d ı· loııdiyor. lngilterenin altı aeneden beri en yiİI<· •..ı. milli müdafaa bütçeoidir. Deniz, ka = T·· k. ·ı · d - te rısat a ın a smet ~· ve han kuvvetleri için 1934 aenesin ur ıye ı e unanıstan arasın a == p F k d b t Je aarfedilecek para, yüz yirmi mrlyon lngiliz Jiraıma yaklll§ıyor. Bunun aıağı - k .. ere mı· ? = aşanın ır a a eyana 'YUkan, yamı donanmaya ıarfedilecek. ~~ye kalan altmıı milyonun da üçte as e apı ıyor. .. İkisi orduya Ye Üçte biri havaya tahsiı edilecelııtir. Gerçi Waşington ve Londra Misakın Yunan meclisinde İnüna- Tetkikat yapmak uzere Fırkada bir d~niz 111üları mukaveleleri, lngiltere "!n 1936 -.i sonuna kadar daha ge - k k b - komisyon teşkiline "~f _ınikyaeta harp gemisi yapmasına ma ";'dir. -

29Th June 2003 Pigs May Fly Over TV Studios by Bob Quinn If Brian

29th June 2003 Pigs May Fly Over TV Studios By Bob Quinn If Brian Dobson, Irish Television’s chief male newsreader had been sacked for his recent breach of professional ethics, pigs would surely have taken to the air over Dublin. Dobson, was exposed as doing journalistic nixers i.e. privately helping to train Health Board managers in the art of responding to hard media questions – from such as Mr. Dobson. When his professional bilocation was revealed he came out with his hands up – live, by phone, on a popular RTE evening radio current affairs programme – said he was sorry, that he had made a wrong call. If long-standing Staff Guidelines had been invoked, he might well have been sacked. Immediately others confessed, among them Sean O’Rourke, presenter of the station’s flagship News At One. He too, had helped train public figures, presumably in the usual techniques of giving soft answers to hard questions. Last year O’Rourke, on the live news, rubbished the arguments of the Chairman of Primary School Managers against allowing advertisers’ direct access to schoolchildren. O’Rourke said the arguments were ‘po-faced’. It transpires that many prominent Irish public broadcasting figures are as happy with part-time market opportunities as Network 2’s rogue builder, Dustin the Turkey, or the average plumber in the nation’s black economy. National radio success (and TV failure) Gerry Ryan was in the ‘stable of stars’ run by Carol Associates and could command thousands for endorsing a product. Pop music and popcorn cinema expert Dave Fanning lucratively opened a cinema omniplex. -

Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018

The 100% Unofficial Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 O Guia Rápido 100% Não-Oficial do Eurovision Song Contest 2018 for Commentators Broadcasters Media & Fans Compiled by Lisa-Jayne Lewis & Samantha Ross Compilado por Lisa-Jayne Lewis e Samantha Ross with Eleanor Chalkley & Rachel Humphrey 2018 Host City: Lisbon Since the Neolithic period, people have been making their homes where the Tagus meets the Atlantic. The sheltered harbour conditions have made Lisbon a major port for two millennia, and as a result of the maritime exploits of the Age of Discoveries Lisbon became the centre of an imperial Portugal. Modern Lisbon is a diverse, exciting, creative city where the ancient and modern mix, and adventure hides around every corner. 2018 Venue: The Altice Arena Sitting like a beautiful UFO on the banks of the River Tagus, the Altice Arena has hosted events as diverse as technology forum Web Summit, the 2002 World Fencing Championships and Kylie Minogue’s Portuguese debut concert. With a maximum capacity of 20000 people and an innovative wooden internal structure intended to invoke the form of Portuguese carrack, the arena was constructed specially for Expo ‘98 and very well served by the Lisbon public transport system. 2018 Hosts: Sílvia Alberto, Filomena Cautela, Catarina Furtado, Daniela Ruah Sílvia Alberto is a graduate of both Lisbon Film and Theatre School and RTP’s Clube Disney. She has hosted Portugal’s edition of Dancing With The Stars and since 2008 has been the face of Festival da Cançao. Filomena Cautela is the funniest person on Portuguese TV. -

Ufukta Bizi Tehdid Eden Bir Hadise Yoktur!

CUMA TAN EVi Casetecilik, MatLaacılık, ICliıecilik Okuyucularımızı TELEFON ı Z4318, %4319, 24310. 29 TELGRAF ı T A N , l.taabal 1000 Liraya MAYIS lKlNCl YIL No. !9L 1936 5 KURUŞ Sigorta Ediyoruz GÜNDELiK GAZETE Ufukta bizi tehdid eden bir hadise yoktur! ismet lnönu muhim bir nutuk söyledi Askeri tatbikat Müdafaa vasıtalarımızı fennin en yeni Atatürk uçaklarımızıft gece hareketlerini icatlarına göre teçhiz etmekteyiz ! yakınd~n takip ettiler Umumi müvazene İstanbul, 28 (A.A.) - Harp akademisi tarafından Eğer ufkun arkasında görmediğimiz yapılan ve 2 8 mayıs sabahı başlayan tümen tatbikatı es Kanun Mecliste nasında bilhassa tayyarecilerin gece harekatını takip et tehlike varsa ondan da korkmuyoruz mek üzere Reisicümhur Atatürk 28 mayıs saat 24 te tat dün ittifakla bikat sahasını teşrif etmişler ve harekatı takibe başla mışlardır. Meclis itti/akla hükumete itimadını bildirdi kabul edildi hkara, 28 (A.A.) -Kamutay bu na getirdiğimiz eser, hakiki manasiy tun Abdülhalik Rendanm başkanh le tam ve mütevazin bir bütçedir. fında yaptığı toplantıda 1936 bütçe• - Arkadaşlar , bilhassa son sene ltalya, Türkiye ve Yunanistan •lnin müzakeresini bitirmiştir. Bu mü lerde biltün dünyanın geçirdiği iktı nasebetle söz alan Başbakan !smet sadi şartlar yüzünden meydana çı ile olan dostluk misakına lnönU aşağıdaki beyanatta bulun • kan ve bütçe muvazenesi kadar mü• !nuştur: him olan diğer bir amil, döviz muva hürmet etmek kararındadır Arkadaşlar, zenesi vardır. Biz, gerek bütçede ve Londra, 28 (A.A.) - Daily Teleg Devlet hizmetlerinin tatbik oluna gerek mali siyasetimizde döviz mu raf gazetesinin muhabiri ile bir ko takları sahayı gösteren bütçe müza• vazenesini ciddi bir surette temin et nuşma ynpan Mussolini ezcümle şun keresi sona ermiştir. Vekil arkadaş mek için çok kayıtlı bulunuyoruz. -

The Echo 7.Pdf

ISSUE 7 // OCTOBER 2013 THE ECHO OBBY AITKEN | GILL ALLEN | RACHEL ARCHIBALD | PAUL ARDITTI | CHRISTOPHER ASHWORTH | TOM ASPLEY | HELEN ATKINSON | KELSH B-D | DAN BAILEY | SIMON BAK DANIEL BALFOUR | HAMISH BAMFORD | ALEX BARANOWSKI | HARRY BARKER | CHRIS BARLOW | DAVID BARTHOLOMEUSZ | MIKE BEER | SIMON BEESLEY | RICHARD BE OB BETTLE | DOMINIC BILKEY | SIMON BIRCHALL | ZOE BLACKFORD | BRYONY BLACKLER | MARK BODEN | FRANK BRADLEY | AMY BRAMMA | DANNY BRIGHT | ALICE BROO TEVEN BROWN | NELA BROWN | RACHEL BROWN | ROSS BROWN | BORNEO BROWN | ANDREW BRUCE | CLIVE BRYAN | RICHARD BUGG | PAUL BULL | DAVID BURTON | HAR UTCHER | ALEX CAPLEN | RICHARD CARTER | SAM CHARLESTON | KERI DANIELLE CHESSER | KARL CHRISTMAS | GEORGE CHRISTOU | THOMAS CLACHERS | SHAUN CLARK | E LARKE | RICK CLARKE | GREGORY CLARKE | SAMUEL CLARKSON | ANDY COLLINS | JACK CONDELL | CRISPIAN COVELL | TOM COX | ANDREA J COX | MATT DANDO | BEN DAVI ONY DAVIES | SIMON DEACON | STUART DEAN | GEORGE DENNIS | IAN DICKINSON | ROBERT DONNELLY-JACKSON | CAROLYN DOWNING | OLIVER DRIVER | CHRIS DROHA RALPH DUNLOP | JEREMY DUNN | MARK DUNNE | ALEX DURRELL | CHANTELLE DYSON | STEPHEN EDWARDS | ED ELBOURNE | JEREMY ELLIS | PETER ELTRINGHAM ADISONTips ENGLISH and | GARETH tricks EVANS of| DAN the EVANS |trade AARON EVANS | CHRISTOPHER EVANS | ED FERGUSON | GREGG FISHER | ADAM FISHER | JAMIE FLOCKTON | AND ANKSFrom | SEBASTIAN Terry Jardine,Mic FROST | GARETH Pool, FRY Andrew| CHRIS FULL Bruce, | ADAM John FUNNELL Leonard, | PAUL Gareth GAVIN | Fry,JEREMY GEORGE | TUOMO GEORGE-TOLONEN | TOM -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR.