From Sufism to Ahmadiyya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musleh Maud: the Promised Reformer

PROPHECY OF MUSLEH MAUD: THE PROMISED REFORMER REF: FRIDAY SERMON (20.2.15) Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad as (1835-1908) The Promised Messiah and Imam Mahdi 1) Hadhrat Al-Haaj Maulana Hakeem Nooruddin Khalifatul Masih I (ra) 2) Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmood Ahmad First Successor to the Promised Messiah (as) “Musleh Maud“(ra) Period of Khilafat: 1908-1914 Khalifatul Masih II Second Successor to the Promised Messiah. (as) Period of Khilafat: 1914 –1965 3) Hadhrat Mirza Nasir Ahmad Khalifatul Masih III (rh) 4) Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad Third Successor to the Promised Messiah (as) Khalifatul Masih IV(rh) Period of Khilafat: 1965-1982 Fourth Successor to the Promised Messiah (as) Period of Khilafat: 1982 - 2003 5) Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad Khalifatul Masih V (aba) Fifth Successor to the Promised Messiah (as) Period of Khilafat: 2003- present day . KHALIFATUL MASIH II Name: Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmood Ahmad Musleh Maud Khalifatul Masih II Second Successor to the Promised Messiah (ra) Date of Birth: January 12th 1889 Period of Khilafat: 1914 –1965 He was 25 years of age when he became Khalifa Passed Away: On November 8, 1965 Musleh Maud: 28th Jan 1944 – claimed to be the Promised Son ‘Musleh Maud’ (The Promised Reformer) Photographs of Khalifatul Masih II (ra) PROPHECY OF MUSLEH MAUD Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmood Ahmad (ra) was the second successor of the Promised Messiah (as). He was a distinguished (great) Khalifa because his birth was foretold by a number of previous Prophets and Saints. The Promised Messiah (as) received a Divine sign for the truth of Islam as a result of his forty days of prayer at Hoshiarpur (India). -

Surah Al-Anfal Tafsir – Nouman Ali Khan Lecture Notes

بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم Surah Al-Anfal Tafsir – Nouman Ali Khan Lecture Notes Introduction and Verse 1 The introduction of this Surah is quite long but it is significant and very important to set the stage for what is about to follow. This is part of a series of surahs – Surah Anfal and Surah Taubah. This surah is related to the previous surah (Surah A’raf) in that they both talk about the ‘Sunnah of Allah’ (Sunnatillah). It talks about how Allah deals with similar Nations in the same way. It is mentioned in the Qur’an: [This is] the established way of Allah with those who passed on before; and you will not find in the way of Allah any change. [33:62] In the second half of Surah A’raf, Allah talks about the worldly destruction of nations and people that came before, specially the people of Musa and the destruction and drowning of Fir’awn and in Surah Anfal Allah will talk about the destruction of the people of Makkah (NOT the entire Arabian Peninsula). The Makkans here will be destroyed and defeated by the very swords of the believers – the army behind Rasulallah (s). It is not going to be fire from the skies, not a flood or an earthquake but the companions themselves. Part of the Sunnah of Allah is that punishments usually come down in two different forms: 1. Smaller punishments are sent as warnings before it is too late for example the nine signs of Musa(as) 2. Eventually the greater and major punishment is sent down for example the drowning of Fir’awn. -

Race, Rebellion, and Arab Muslim Slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Race, rebellion, and Arab Muslim slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E. Nicholas C. McLeod University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, History of Religion Commons, Islamic Studies Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation McLeod, Nicholas C., "Race, rebellion, and Arab Muslim slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2381. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2381 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, REBELLION, AND ARAB MUSLIM SLAVERY: THE ZANJ REBELLION IN IRAQ, 869 - 883 C.E. By Nicholas C. McLeod B.A., Bucknell University, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In Pan-African Studies Department of Pan-African Studies University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Nicholas C. -

Al-Nahl Volume 13 Number 3

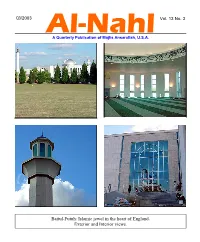

Q3/2003 Vol. 13 No. 3 Al-Nahl A Quarterly Publication of Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. Baitul-Futuh: Islamic jewel in the heart of England. Exterior and Interior views. Special Issue of the Al-Nahl on the Life of Hadrat Dr. Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, radiyallahu ‘anhu. 60 pages, $2. Special Issue on Dr. Abdus Salam. 220 pages, 42 color and B&W pictures, $3. Ansar Ansar (Ansarullah News) is published monthly by Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. and is sent free of charge to all Ansar in the U.S. Ordering Information: Send a check or money order in the indicated amount along with your order to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905. Price includes shipping and handling within the continental U.S. Conditions of Bai‘at, Pocket-Size Edition Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. has published the ten conditions of initiation into the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in pocket size brochure. Contact your local officials for a free copy or write to Ansar Publications, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring MD 20905. Razzaq and Farida A story for children written by Dr. Yusef A. Lateef. Children and new Muslims, all can read and enjoy this story. It makes a great gift for the children of Ahmadi, Non-Ahmadi and Non- Muslim relatives, friends and acquaintances. The book contains colorful drawings. Please send $1.50 per copy to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905 with your mailing address and phone number. Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. will pay the postage and handling within the continental U.S. -

The Review of Religions, May 1988

THE REVIEW of RELIGIONS VOL LXXXIII NO. 5 MAY 1988 IN THIS ISSUE EDITORIAL GUIDE POSTS • SOURCES OF SIRAT • PRESS RELEASE • PERSECUTION IN PAKISTAN • ISLAM AND RUSSIA • BLISS OF KHILAFAT > EIGHTY YEARS AGO MASJID AL-AQSA THE AHMADIYYA MOVEMENT The Ahmadiyya Movement was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the expected world reformer and the Promissed Messiah whose advent had been foretold by the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be on him). The Movement is an embodiment of true and real Islam. It seeks to unite mankind with its Creator and to establish peace throughout the world. The present head of the Movement is Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. The Ahm-adiyya Movement has its headquarters at Rabwah, Pakistan, and is actively engaged in missionary work. EDITOR: BASHIR AHMAD ORCHARD ASSISTANT EDITOR: NAEEM OSMAN MEMON MANAGING EDITOR: AMATUL M. CHAUDHARY EDITORIAL BOARD B. A. RAFIQ (Chairman) A. M. RASHED M. A. SAQI The REVIEW of RELIGIONS A monthly magazine devoted to the dissemination of the teachings of Islam, the discussion of Islamic affairs and religion in general. \f The Review of Religions is an organ of the Ahmadiyya CONTENTS Page Movement which represents the pure and true Islam. It is open to all for discussing 1. Editorial 2 problems connected with the religious and spiritual 2. Guide Posts 3 growth of man, but it does (Bashir Ahmad Orchard) not accept responsibility for views expressed by 3. Sources of Sirat contributors. (Hazrat Mirza Bashir Ahmad) 4. Press Release 15 All correspondence should (Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry)' be forwarded directly to: 5. Persecution in Pakistan 16 The Editor, (Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry) The London Mosque, 16 Gressenhall Road, 6. -

Review of Religions Centenary Message from Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih IV

Contents November 2002, Vol.97, No.11 Centenary Message from Hadhrat Ameerul Momineen . 2 Editorial – Mansoor Shah . 3 Review of Religions: A 100 Year History of the Magazine . 7 A yearning to propogate the truth on an interntional scale. 7 Revelation concerning a great revolution in western countries . 8 A magazine for Europe and America . 9 The decision to publish the Review of Religions . 11 Ciculation of the magazine . 14 A unique sign of the holy spirit and spiritual guidance of the Messiah of the age. 14 Promised Messiah’s(as) moving message to the faithful members of the Community . 15 The First Golden Phase: January 1902-May 1908. 19 The Second Phase; May 1908-March 1914 . 28 Third Phase: March 1914-1947 . 32 The Fourth Phase: December 1951-November 1965. 46 The Fifth Phase: November 1965- June 1982 . 48 The Sixth Phase: June 1982-2002 . 48 Management and Board of Editors. 52 The Revolutionary articles by Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. 56 Bright Future. 58 Unity v. Trinity – part II - The Divinity of Jesus (as) considered with reference to the extent of his mission - Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as) . 60 Chief Editor and Manager Chairman of the Management Board Mansoor Ahmed Shah Naseer Ahmad Qamar Basit Ahmad. Bockarie Tommy Kallon Special contributors: All correspondence should Daud Mahmood Khan Amatul-Hadi Ahmad be forwarded directly to: Farina Qureshi Fareed Ahmad The Editor Fazal Ahmad Proof-reader: Review of Religions Shaukia Mir Fauzia Bajwa The London Mosque Mansoor Saqi Design and layout: 16 Gressenhall Road Mahmood Hanif Tanveer Khokhar London, SW18 5QL Mansoora Hyder-Muneeb United Kingdom Navida Shahid Publisher: Al Shirkatul Islamiyyah © Islamic Publications, 2002 Sarah Waseem ISSN No: 0034-6721 Saleem Ahmad Malik Distribution: Tanveer Khokhar Muhammad Hanif Views expressed in this publication are not necessarily the opinions of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. -

The Detroit Address

The Detroit Address by Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad rta Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya USA The Detroit Address An English translation of the Friday Sermon delivered by by Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad , Khalifatul-Masih IV rta on October 16th, 1987 at Detroit, Michigan, United States of America First published in USA, 1987 Republished in USA, 2018 © MKA USA Publications Ltd. Published by Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya USA Isha‘at Department 15000 Good Hope Rd. Silver Spring, Maryland 20905, USA For further information please visit www.alislam.org. ISBN 978-0-9990794-1-6 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents About The Author ............................................... v Foreword ...........................................................vii The Detroit Address ................................... 1 Publisher’s Note ................................................37 Glossary ............................................................41 Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad Khalifatul-Masih IV rta About The Author Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (December 18th, 1928 – April 19th 2003), Khalifatul-Masih IV rta, was the supreme head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. He was elected as the fourth successor of Hadrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad as, the Promised Messiah, on June 10th 1982. Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad passed away on April 19th, 2003. His successor, Hadrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad atba, is the present Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Hadrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad was born on December 18th, 1928, in Qadian, India, to Hadrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad ra and Hadrat Syeda Maryam Begum. He received his early schooling in Qadian before immigrating to Pakistan, where he completed his Shahid Degree with dis- tinction from Jamia‘ [Theological Academy] Ahmadiyya Rabwah and an Honors degree in Arabic from Punjab viii The Detroit Address University. -

Aug-Sep 1970

BISMILLA-HIR-RAHMANIR-RAHIM THE AHMADIYYA GAZETTE AUG - SEP 1970 VOL. IX - NO. 8 Li'Pb'^ (Holy Quran, 4:96; 8:73) NO organization, religious or secular, can propser without money. This is why, when Allah exhorts the believers to strive in His cause. He j •a.i. .. oarticularly to be the case in the Latter Days, this S®why^n?*Holy^Prophet, 'peace and blessings of Allah be on him said, when ^e promised Messiah comes, he will abolish physical fighting, in other wor^, l*ere would be no need of fighting physical battles for the propagation of course, "Jihad" there must be, and more intense and longer, but not with the bo y and the sworD, but with money and pen. The Promised Messiah, peace be on him, has come, and has declared war- with the forces of evil. To carry on this war he has demanded from his followers moneta^ contribution and not physical fighting. His Second Khalifa (Successor) regularizeD this contribution, and fixed it to be at least, l/16th of one's mon^ly income and further enunciated that one who does not contribute at this rate, without legitimate grounds, and securing permission to pay at a lesser rate, shall not be co^idere sincere and true Ahmadis. He further declared definitely that one who fails to pay, at this rate, without any reasonable excuse, for consecutive six months, shall not be entitled to vote or be eligible for any office of the Jamat (Comm^ity). TUimadis in Pakistan have been, by the Grace of Allah, regularly paying a is ra e, many (about twenty five thousand Ahmadis v4io are called "Musis") are paying 1/lOth and some even 1/3, and Allah, too, has been showering His Blessing upon them and increasing their income, and they, too, are giving, ever more and more. -

Download Book

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE RELIGIOUS LIFE OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL, YOUNG MEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA AND CEYLON ; AND NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. ALREADY PUBLISHED THE VILLAGE GODS OF SOUTH INDIA. By the Bishop OF Madras. VOLUMES UNDER PREPARATION THE VAISHNAVISM OF PANDHARPUR. By NicoL Macnicol, M.A., D.Litt., Poona. THE CHAITANYAS. By M. T. Kennedy, M.A., Calcutta. THE SRI-VAISHNAVAS. By E. C. Worman, M.A., Madras. THE SAIVA SIDDHANTA. By G. E. Phillips, M.A., and Francis Kingsbury, Bangalore. THE VIRA SAIVAS. By the Rev. W. E. Tomlinson, Gubbi, Mysore. THE BRAHMA MOVEMENT. By Manilal C. Parekh, B.A., Rajkot, Kathiawar. THE RAMAKRISHNA MOVEMENT. By I. N. C. Ganguly, B.A., Calcutta. THE StJFlS. By R. Siraj-ud-Din, B.A., and H. A. Walter, M.A., Lahore. THE KHOJAS. By W. M. Hume, B.A., Lahore. THE MALAS and MADIGAS. By the Bishop of Dornakal and P. B. Emmett, B.A., Kurnool. THE CHAMARS. By G. W. Briggs, B.A., Allahabad. THE DHEDS. By Mrs. Sinclair Stevenson, M.A., D.Sc, Rajkot, Kathiawar. THE MAHARS. By A. Robertson, M.A., Poona. THE BHILS. By D. Lewis, Jhalod, Panch Mahals. THE CRIMINAL TRIBES. By O. H. B. Starte, I.C.S., Bijapur. EDITORIAL PREFACE The purpose of this series of small volumes on the leading forms which religious life has taken in India is to produce really reliable information for the use of all who are seeking the welfare of India, Editor and writers alike desire to work in the spirit of the best modern science, looking only for the truth. -

The Legalization of Theology in Islam and Judaism in the Thought of Al-Ghazali and Maimonides

UC Berkeley Berkeley Journal of Middle Eastern & Islamic Law Title Law as Faith, Faith as Law: The Legalization of Theology in Islam and Judaism in the Thought of Al-Ghazali and Maimonides Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hm3k78p Journal Berkeley Journal of Middle Eastern & Islamic Law, 6(1) Author Pill, Shlomo C. Publication Date 2014-04-01 DOI 10.15779/Z38101S Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 1 BERKELEY J. OF MIDDLE EASTERN & ISLAMIC LAW 2014 LAW AS FAITH, FAITH AS LAW: THE LEGALIZATION OF THEOLOGY IN ISLAM AND JUDAISM IN THE THOUGHT OF AL-GHAZALI AND MAIMONIDES Shlomo C. Pill1 I. INTRODUCTION Legal systems tend to draw critical distinctions between members and nonmembers of the legal-political community. Typically, citizens, by virtue of shouldering the burden of legal obligations, enjoy more expansive legal rights and powers than noncitizens. While many modern legal regimes do offer significant human rights protections to non-citizens within their respective jurisdictions, even these liberal legal systems routinely discriminate between citizens and non- citizens with respect to rights, entitlements, obligations, and the capacity to act in legally significant ways. In light of these distinctions, it is not surprising that modern legal systems spend considerable effort delineating the differences between citizen and noncitizen, as well as the processes for obtaining or relinquishing citizenship. As nomocentric, or law-based faith traditions, Islam and Judaism also draw important distinctions between Muslims and non-Muslims, Jews and non- Jews. In Judaism, only Jews are required to abide by Jewish law, or halakha, and consequently only Jews may rightfully demand the entitlements that Jewish law duties create, while the justice owed by Jews to non-Jews is governed by a general rule of reciprocity. -

35 Ahmadiyya

Malaysian Journal of International Relations, Volume 6, 2018, 35-46 ISSN 2289-5043 (Print); ISSN 2600-8181 (Online) AHMADIYYA: GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF A PERSECUTED COMMUNITY Abdul Rashid Moten ABSTRACT Ahmadiyya, a group, founded in 19th century India, has suffered fierce persecution in various parts of the Muslim world where governments have declared them to be non-Muslims. Despite opposition from mainstream Muslims, the movement continued its proselytising efforts and currently boasts millions of followers worldwide. Based on the documentary sources and other scholarly writings, this paper judges the claims made by the movement's founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, analyses the consequences of the claims, and examines their proselytizing strategies. This paper found that the claims made by Mirza were not in accordance with the belief of mainstream Muslims, which led to their persecution. The reasons for their success in recruiting millions of members worldwide is to be found in their philanthropic activities, avoidance of violence and pursuit of peace inherent in their doctrine of jihad, exerting in the way of God, not by the sword but by the pen. Keywords: Ahmadiyya, jihad, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Pakistan, philanthropy INTRODUCTION The Qur’an categorically mentions that Muhammad is the last in the line of the Prophets and that no prophet will follow him. Yet, there arose several individuals who claimed prophethood in Islam. Among the first to claim Prophecy was Musailama al-Kazzab, followed by many others including Mirza Hussein Ali Nuri who took the name Bahaullah (glory of God) and formed a new religion, the Bahai faith. Many false prophets continued to raise their heads occasionally but failed to make much impact until the ascendance of the non-Muslim intellectual, economic and political forces particularly in the 19th century A.D. -

Socrates(As) – Development of Greek Philosophy and Religion

The object of this publication, produced by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, is to educate, enlighten and inform its readers on religious, social, economic and political issues with particular emphasis on Islam. EDITORIAL BOARD CONTENTS – December 2001, Vol.96, No.12 Chairman: Rafiq Hayat Fazal Ahmad, Sarah Waseem, Editorial ............................................... 2 Fauzia Bajwa, Fareed Ahmad, Basit Ahmad, Mansoor Saqi, Bockarie Tommy Kallon, Comment .............................................. 3 Navida Shahid, Mahmood Hanif, Fazal Ahmad – UK Tanveer Khokhar, Mansoora Hyder-Muneeb, Saleem Ahmad Malik. The History and Theory of Islamic Medicine.................................. 5 Chairman of the Mrs Samina Mian – Edmonton Management Board: Naseer Qamar Assessment of Belief – Part I.............. 16 Special Contributor: Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad(as) Amatul-Hadi Ahmad Design and Typesetting Chirality and Sideness in Tanveer Khokhar Nature ................................................... 23 Shaukia Mir Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad Publisher Al Shirkatul Islamiyyah Socrates(as) – Development of Greek Philosophy and Religion.......... 33 Distribution Muhammad Hanif, Fazal Ahmad – UK Amatul M. Chaudry, M.D. Shams Division and Unity.. ............................. 44 Views expressed in this publication are not necessarily Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad the views of the A h m a d i y y a Muslim Community A Unique Cosmic Heavenly Sign........ 52 M. Alikoya – India All correspondence should be forwarded directly to: Index of 2001 Artcicles........................ 62 The Editor Review of Religions The London Mosque 16 Gressenhall Road London, SW18 5QL United Kingdom © Islamic Publications, 2000 (Photo: From ArtExplosion Photo ISSN No. 0034-6721 library) Editorial The realm of medicine has fascinated Mirza Tahir Ahmad in his outstanding man for centuries. Particularly with the work R a t i o n a l i t y, Revelation, expectation of a longer and a healthier Knowledge and Truth.