Prospects for Codifying the Relationship Between Central and Local Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fisher Lane Park Project Blossoms

Winter 2016/2017 WolvesON the High Street inreturn Mansfield Woodhouse to isMansfield a cottage Woodhouse called Wolf Hunt House and it is reputed that long ago the man who lived there had the job of keeping the area free from wolves. The wolves are back in Mansfield Woodhouse again. This time though they are part of a new community artwork on the Millennium Green. Created by Nottingham based carver Mark Manders, the sculpture was carved out of an old ash tree that was felled in 2014. Carving Children from the Bramble and Manor Academies attended a workshop where they heard about the natural history of the Green. After this session the children submitted suggestions for the design of the carving and Mark interpreted these to produce the finished work. The carving was commissioned by the Mansfield funding organisation dedicated to making lasting Woodhouse Millennium Green Trust and funded by a improvements to the natural environment and grant from the SUEZ Communities Trust; an ethical community life. It’s a big year for 2016volunteers has been a busy time for Friends Groups across the district. Thanks to the support of Friends Groups a large number of conservation projects have been completed in Mansfield’s open spaces and nature reserves. The year saw a wide range of activities • The opening of the picnic site at Quarry from litter picks, bulb planting, the creation Lane Nature Reserve was just one of the of orchards and wildflower meadows and many successful projects in 2016. development of wildlife habitats. For further details about how to get Volunteers donated thousands of hours involved in future projects, please email of their time to help out and together Mansfield District Council’s parks team at they’ve made a huge difference. -

Pride Lineup R Ee Qb

F PRIDE LINEUP R EE QB Nottinghamshire’s Queer Bulletin August/September 2011 Number 61 The Pride stage will undergo meiosis and divide into 4. As well as the Main Stage (hosted by Harry Derbridge - from “The only way is Essex”), Politicians experience often scath- you can enjoy the Acoustic Stage, the Comedy Stage and a family zone - ing criticism on a daily basis in our The Village Green. Some of the performers featured are listed below. newspapers. On radio and televi- sion they are subject to the mock- MAIN STAGE ACOUSTIC STAGE COMEDY STAGE ery which is part of a tradition going Booty Luv Kenelis Julie Jepson back to - at least - the ancient Ruth Lorenzo Maniére des Suzi Ruffle Greeks. Cartoonists have a field day. David Cameron is portrayed Drag with No Name Bohémiens Rosie Wilby by one as a "Little Lord Fauntleroy" Fat Digester Gallery 47 Rachel Stubbins type and by another as a pink hu- Propaganda Betty Munroe & Josephine Ettrick-Hogg man condom with big wobbly Danny Stafford The Blue Majestix Carly Smallman Youth Spot The Idolins breasts. VILLAGE GREEN Jo Francis Emily Franklin Our mockery and fact-based criti- Captain Dangerous Wax Ersatz Asian Dance Group cisms of Kay Cutts pale beside this Vibebar May KB Pirate Show and beside what one reads on the Benjamin Bloom Selma Thurman Carlton Brass Band local Parish of Nottinghamshire Grey Matter Ball Bois display website, to which we referred. Poli- The Cedars Hosts: John Gill & Dog display team ticians need broad shoulders. Bear- NG1/@D2 Princess Babserella Tatterneers Band ing in mind the size of Mrs Cutts' "shoulders", the County Library QB ban is utterly predictable. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Mayoral Election Address Book

Council of the Borough of North Tyneside Mayoral Election Address Book Your guide to the election, candidates and how to vote 6 May 2021 Mayoral Election - 6 May 2021 Introduction Voting at the Mayoral Election On 6 May 2021, you, the residents and voters of Five candidates are standing for election for the Mayor of North North Tyneside will be able to vote in the election Tyneside. They will be listed alphabetically on the ballot paper. to choose the Mayor of North Tyneside. The Mayoral candidates are: About this booklet John Christopher Appleby This booklet must be sent to you by law*. Liberal Democrat It includes: _________________________________ l Information about the election Norma Redfearn l An election address (i.e. a statement) from Labour Party each of the Mayoral candidates who wish to _________________________________ be included in this booklet Penny Remfry l Information on how to fill in your ballot paper Green Party and how the result will be calculated _________________________________ l Frequently asked questions Steven Paul Robinson Your vote is important in deciding who the future The Conservative Party Candidate Mayor of North Tyneside will be. _________________________________ Bryn Roberts Jack James Thomson Returning Officer UK Independence Party (UKIP) _________________________________ Each candidate was given the opportunity to provide an election *One booklet must be distributed to each registered elector. address to be included in this booklet. All candidates chose to do so This booklet has been produced in accordance with The Local and they have each paid £750 towards the printing cost of the booklet. Authorities (Mayoral Elections) (England and Wales) Regulations 2007. -

Public Questions for Full Council

Accepted / Date Question to Question Reason Rejected 05/03/2019 Mayor Can the Mayor confirm if she thinks 2 hours free parking will increase footfall within Mansfield Town Accepted centre? Mayor Do you think putting some council services such as a cash office, housing and homelessness officers, Accepted front desk customer enquiries in to our Town Hall on Mansfield Market Place would make council services more accessible and increase footfall in our town centre? Mayor Mansfield is the only authority in the County that has an Executive Mayor instead of a council leader. In Accepted the other Nottinghamshire Local Authorities the average allowance for the council leaders is just over £19,000 p.a. How does the current Mayor justify the £60,000 a year she currently receives? 21/05/2019 Mayor "Many congratulations to the Mayor on winning the election. During the campaign, many residents Withdrawn complained about the cost of the position of the Mayor. In response, I suggested to cut the mayoral allowance by about two thirds. You then offered to take a pay cut of about a third. I think that this is a positive compromise. I wonder if the Mayor would consider another compromise whereby the allowances and expenses of all the elected representatives in Mansfield are brought down to levels that are more consistent with other districts in Nottinghamshire, so that more money can be invested in our community?" 16/07/2019 Mayor A sum of public money in the region of £500,000 is required annually for the next four years amounting Accepted to £2,000,000. -

DRAFT Key Decision/Action Points from Board

Item 1.3: CONFIRMED Key Decision/Action Points from Board D2N2 LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP BOARD MEETING Wednesday, 19 May, 2021 By Teams Dial-In Chair Elizabeth Fagan CBE Minutes Sally Hallam 1. Present and Apologies D2N2 Board Members in Attendance James Brand Business Representative Andrew Cropley F E Representative Michele Farmer Inclusion and Diversity Representative Tim Freeman Business Representative Clare James Business Representative Jayne Mayled Business Representative Cllr David Mellen Leader, Nottingham City Council Cllr Chris Poulter Leader, Derby City Council Becky Rix Business Representative Viv Russell Business Representative Cllr Simon Robinson Rushcliffe Borough Council, N2 representative Prof Shearer West, CBE HE Representative David Williams Deputy Chair/Business Representative Susan Caldwell LEP Sponsor Also in attendance Cllr Keith Girling Observer, Nottinghamshire County Council Scott Knowles CEO, East Midlands Chamber Gill Callingham Director at N E Derbyshire DC Anthony May CEO, Nottinghamshire County Council Adrian Smith Deputy CEO Nottinghamshire County Council Cara Prendergast rep for Rushcliffe Borough Council David Fletcher Director at Derby City Council Nicki Jenkins Director at Nottingham City Council Emma Alexander Executive Director, Derbyshire County Council Officer Support Sajeeda Rose Chief Executive, D2N2 Tom Goshawk Head of Capital Programmes, D2N2 Will Morlidge Head of Policy and Strategy Michelle Reynolds Operations Manager, D2N2 Rob Harding Head of Marketing and Communications, D2N2 Kiran Birring -

Homelessness Prevention Strategy 2018

Wolverhampton WV1 1SH City of Wolverhampton Council, Civic Centre, St. Peter’s Square, St.Peter’s Council,Civic Centre, City ofWolverhampton wolverhampton. audio orinanotherlanguagebycalling01902 551155 You can get this information in large print, braille, WolverhamptonToday Wolverhampton_Today @WolvesCouncil gov.uk gov.uk 01902 551155 WCC 1875 05/2019 wolverhampton. andIntervention #Prevention 2018 -2022 Strategy Prevention Homelessness Chapter title gov.uk Contents Foreword Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Development of the strategy 6 Defining Homelessness 6 National Context 7 Homelessness Data 8 Homelessness Prevention and Relief 9 UK Government Priorities 10 West Midlands Combined Authority 11 Local Context 12 Since the publication of our last Homelessness Strategy, we have seen dramatic changes to the Demographic Data 13 environment in which homelessness services are delivered. Changes resulting from the economic downturn, and in particular welfare reform, are impacting Under One Roof 13 detrimentally on many low- income groups and those susceptible to homelessness. Well documented Strategic Context 15 funding cuts to Councils are coupled with falls in support and funding streams to other statutory agencies, and those in the voluntary and community sector. Homelessness Strategy 2018-2022 16 As a result, this new strategy is being developed in a context of shrinking resources and increasing demand for services. There is also considerable uncertainty over the future. Homelessness prevention 16 These factors weigh heavily on the determination of what can realistically be achieved in the years Rough Sleepers 18 ahead. Nevertheless, the challenge and our aspiration remains to prevent homelessness wherever possible in line with the new Homelessness Reduction Act. Vulnerability and Health 19 The response to this challenge will be based on the same core principle as that which underpinned Vulnerabilities 20 our previous strategies effective partnership working. -

Tfem Papers 15 June 2020

Board Meeting 15th June 2020 10.00am to 11.30am Virtual Meeting via Microsoft Teams AGENDA 1. Introductions and Apologies 2. Minutes of Board Meeting 9th September 2019* 3. Covid 19: Impact on Local Transport Authorities* • Update from DfT • Discussion of Future Trends & Priorities 4. East Midlands Rail Franchise • Update from EMR • Collaboration Agreement with DfT 5. A1 (Peterborough to Blyth) • Short Term Safety Measures • Strategic Enhancements 6. Decarbonising Transport: Setting the Challenge* • Priorities for a TfEM response 7. HS2 Update* • NIC Rail (HS2) Assessment • Access to Toton Summary Document Launch 8. Any Other Business 9. Dates of Future Meetings: • 9th September 2020: 10.00am-12.00pm, Leicestershire County Council (tbc) • 14th December 2020: 10.00am-12.00pm, Leicestershire County Council (tbc) *Paper enclosed TfEM Terms of Reference • To provide collective leadership on strategic transport issues for the East Midlands. • To develop and agree strategic transport investment priorities. • To provide collective East Midlands input into Midlands Connect (and other relevant sub- national bodies), the Department for Transport and its delivery bodies, and the work of the National Infrastructure Commission. • To monitor the delivery of strategic transport investment within the East Midlands, and to highlight any concerns to the relevant delivery bodies, the Department for Transport and where necessary the EMC Executive Board. • To provide regular activity updates to Leaders through the EMC Executive Board. TfEM Membership TfEM -

Staffordshire County Council 5 Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council 1 Sandwell 1 Wolverhampton City Council 1 Stoke on Trent Ci

Staffordshire County Council 5 Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council 1 Sandwell 1 Wolverhampton City Council 1 Stoke on Trent City Council 1 Derby City Council 3 Nottinghamshire County Council 2 Education Otherwise 2 Shropshire County Council 1 Hull City Council 1 Warwickshire County Council 3 WMCESTC 1 Birmingham City Council 1 Herefordshire County Council 1 Worcestershire Childrens Services 1 Essex County Council 1 Cheshire County Council 2 Bedfordshire County Council 1 Hampshire County Council 1 Telford and Wrekin Council 1 Leicestershire County Council 1 Education Everywhere 1 Derbyshire County Council 1 Jun-08 Cheshire County Council 3 Derby City Travellers Education Team 2 Derbyshire LA 1 Education Everywhere 1 Staffordshire County Council 6 Essex County Council 1 Gloustershire County Council 1 Lancashire Education Inclusion Service 1 Leicestershire County Council 1 Nottingham City 1 Oxford Open Learning Trust 1 Shropshire County Council 1 Solihull Council 2 Stoke on Trent LA 1 Telford and Wrekin Authority 2 Warwickshire County Council 4 West Midlands Consortium Education Service 1 West Midlands Regional Partnership 1 Wolverhampton LA 1 Nov-08 Birmingham City Council 2 Cheshire County Council 3 Childline West Midlands 1 Derby City LA 2 Derby City Travellers Education Team 1 Dudley LA 1 Education At Home 1 Education Everywhere 1 Education Otherwise 2 Essex County Council 1 Gloucestershire County Council 2 Lancashire Education Inclusion Service 1 Leicestershire County Council 1 Nottinghamshire LA 2 SERCO 1 Shropshire County Council -

Birmingham City Council (Appellants) V Ali (FC) and Others (FC) (Respondents) Moran (FC) (Appellant) V Manchester City Council (Respondents)

HOUSE OF LORDS SESSION 2008–09 [2009] UKHL 36 on appeal from: [2008]EWCA Civ 1228 [2008]EWCA Civ 378 OPINIONS OF THE LORDS OF APPEAL FOR JUDGMENT IN THE CAUSE Birmingham City Council (Appellants) v Ali (FC) and others (FC) (Respondents) Moran (FC) (Appellant) v Manchester City Council (Respondents) Appellate Committee Lord Hope of Craighead Lord Scott of Foscote Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe Baroness Hale of Richmond Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury Counsel Appellant (Birmingham City Council): Respondent: (Ali): Ashley Underwood QC Jan Luba QC Catherine Rowlands Zia Nabi (Instructed by Birmingham City Council) (Instructed by Community Law Partnership) Appellant: (Moran): Respondent (Manchester City Council): Jan Luba QC Clive Freedman QC Adam Fullwood Zoe Thompson (Instructed by Shelter Greater Manchester Housing (Instructed by Manchester City Council) Centre ) Interveners: Secretary of State for Communities and Interveners: Women’s Aid Federation: Local Government: Stephen Knafler Martin Chamberlain Liz Davies (Instructed by Treasury Solicitors) (Instructed by Sternberg Reed ) Hearing dates: 26 JANUARY, 28 and 29 APRIL 2009 ON WEDNESDAY 1 JULY 2009 HOUSE OF LORDS OPINIONS OF THE LORDS OF APPEAL FOR JUDGMENT IN THE CAUSE Birmingham City Council (Appellants) v Ali (FC) and others (FC) (Respondents) Moran (FC) (Appellant) v Manchester City Council (Respondents) [2009] UKHL 36 LORD HOPE OF CRAIGHEAD My Lords, 1. I have had the privilege of reading in draft the opinion which has been prepared by my noble and learned friend Baroness Hale of Richmond, to which my noble and learned friend Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury has contributed. I agree with it, and for the reasons they have given I would allow both appeals. -

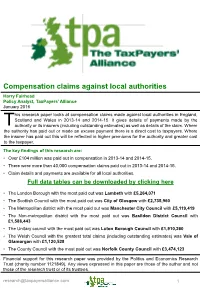

Compensation Claims Against Local Authorities

Compensation claims against local authorities Harry Fairhead Policy Analyst, TaxPayers’ Alliance January 2016 his research paper looks at compensation claims made against local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales in 2013-14 and 2014-15. It gives details of payments made by the T authority or its insurers (including outstanding estimates) as well as details of the claim. Where the authority has paid out or made an excess payment there is a direct cost to taxpayers. Where the insurer has paid out this will be reflected in higher premiums for the authority and greater cost to the taxpayer. The key findings of this research are: • Over £104 million was paid out in compensation in 2013-14 and 2014-15. • There were more than 40,000 compensation claims paid out in 2013-14 and 2014-15. • Claim details and payments are available for all local authorities. Full data tables can be downloaded by clicking here • The London Borough with the most paid out was Lambeth with £5,264,071 • The Scottish Council with the most paid out was City of Glasgow with £2,735,960 • The Metropolitan district with the most paid out was Manchester City Council with £5,119,419 • The Non-metropolitan district with the most paid out was Basildon District Council with £1,588,443 • The Unitary council with the most paid out was Luton Borough Council with £1,910,260 • The Welsh Council with the greatest total claims (including outstanding estimates) was Vale of Glamorgan with £1,120,528 • The County Council with the most paid out was Norfolk County Council with £3,474,123 Financial support for this research paper was provided by the Politics and Economics Research Trust (charity number 1121849). -

Summons to Council

County Hall West Bridgford Nottingham NG2 7QP SUMMONS TO COUNCIL date Thursday, 28 February 2019 venue County Hall, West Bridgford, commencing at 10:30 Nottingham You are hereby requested to attend the above Meeting to be held at the time/place and on the date mentioned above for the purpose of transacting the business on the Agenda as under. Chief Executive 1 Minutes of the last meeting held on 13 December 2018 5 - 22 2 Apologies for Absence 3 Declarations of Interests by Members and Officers:- (see note below) (a) Disclosable Pecuniary Interests (b) Private Interests (pecuniary and non-pecuniary) 4 Chairman's Business a) Presentation of Awards/Certificates (if any) Page 1 of 116 5 Annual Budget 2019-20 23 - 116 Adult Social Care Precept 2019/20 Council Tax Precept 2019/20 Medium Term Financial Strategy 2019/20 to 2022/23 Capital Programme 2019/20 to 2022/23 Capital Strategy 2019/20 NOTES:- (A) For Councillors (1) Members will be informed of the date and time of their Group meeting for Council by their Group Researcher. (2) The Chairman has agreed that the Council will adjourn for lunch at their discretion. (3) (a) Persons making a declaration of interest should have regard to the Code of Conduct and the Procedure Rules for Meetings of the Full Council. Those declaring must indicate whether their interest is a disclosable pecuniary interest or a private interest and the reasons for the declaration. (b) Any member or officer who declares a disclosable pecuniary interest in an item must withdraw from the meeting during discussion and voting upon it, unless a dispensation has been granted.