Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Employment Act of 1946: a Half Century of Experience

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Policy Brief 169 4-1-1996 The Employment Act of 1946: A Half Century of Experience Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L., "The Employment Act of 1946: A Half Century of Experience", Policy Brief 169, 1996, doi:10.7936/K7571960. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/143. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. NOT FOR RELEASE BEFORE 2:00 E.S.T. APRIL 26, 1996 Center for the Study of The Employment Act of 1946: American A Half Century of Experience Business Murray_Weidenbaum C918 Policy Brief 169 April 1996 Contact: Robert Batterson Communications Director (314) 935-5676 Washington University Campus Box 120B One Brookings Drive St. Louis. Missouri 63130-4899 The Employment Act of 1946: A Half Century of Experience by Murray Weidenbaum The first half century of experience under the Employment Act of 1946 (originally the Full Employment Bill of 1945) likely has disappointed both the proponents and the opponents of that innovative law. The impact on national economic policy is neither as bad as the opposition feared nor as substantial as the sponsors had hoped. -

On the Classification of Economic Fluctuations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Explorations in Economic Research, Volume 2, number 2 Volume Author/Editor: NBER Volume Publisher: NBER Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/moor75-2 Publication Date: 1975 Chapter Title: On the Classification of Economic Fluctuations Chapter Author: John R. Meyer, Daniel H. Weinberg Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c7408 Chapter pages in book: (p. 43 - 78) Moo5 2 'fl the 'if at fir JOHN R. MEYER National Bureau of Economic on, Research and Harvard (Jriiversity drawfi 'Ces DANIEL H. WEINBERG National Bureau of Economic iliOns Research and'ale University 'Clical Ihit onth Economic orith On the Classification of 1975 0 Fluctuations and ABSTRACT:Attempts to classify economic fluctuations havehistori- cally focused mainly on the identification of turning points,that is, so-called peaks and troughs. In this paper we report on anexperimen- tal use of multivariate discriminant analysis to determine afour-phase classification of the business cycle, using quarterly andmonthly U.S. economic data for 1947-1973. Specifically, weattempted to discrimi- nate between phases of (1) recession, (2) recovery, (3)demand-pull, and (4) stagflation. Using these techniques, we wereable to identify two complete four-phase cycles in the p'stwarperiod: 1949 through 1953 and 1960 through 1969. ¶ As a furher test,extrapolations were made to periods occurring before February 1947 andalter September 1973. Using annual data for the period 1926 -1951, a"backcasting" to the prewar U.S. economy suggests that the n.ajordifference between prewar and postwar business cycles isthe onii:sion of the stagflation phase in the former. -

Economic Report of the President.” ______

REFERENCES Chapter 1 American Civil Liberties Union. 2013. “The War on Marijuana in Black and White.” Accessed January 31, 2016. Aizer, Anna, Shari Eli, Joseph P. Ferrie, and Adriana Lleras-Muney. 2014. “The Long Term Impact of Cash Transfers to Poor Families.” NBER Working Paper 20103. Autor, David. 2010. “The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market.” Center for American Progress, the Hamilton Project. Bakija, Jon, Adam Cole and Bradley T. Heim. 2010. “Jobs and Income Growth of Top Earners and the Causes of Changing Income Inequality: Evidence from U.S. Tax Return Data.” Department of Economics Working Paper 2010–24. Williams College. Boskin, Michael J. 1972. “Unions and Relative Real Wages.” The American Economic Review 62(3): 466-472. Bricker, Jesse, Lisa J. Dettling, Alice Henriques, Joanne W. Hsu, Kevin B. Moore, John Sabelhaus, Jeffrey Thompson, and Richard A. Windle. 2014. “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2010 to 2013: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, Vol. 100, No. 4. Brown, David W., Amanda E. Kowalski, and Ithai Z. Lurie. 2015. “Medicaid as an Investment in Children: What is the Long-term Impact on Tax Receipts?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 20835. Card, David, Thomas Lemieux, and W. Craig Riddell. 2004. “Unions and Wage Inequality.” Journal of Labor Research, 25(4): 519-559. 331 Carson, Ann. 2015. “Prisoners in 2014.” Bureau of Justice Statistics, Depart- ment of Justice. Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez, and Nich- olas Turner. 2014. “Is the United States Still a Land of Opportunity? Recent Trends in Intergenerational Mobility.” NBER Working Paper 19844. -

"What Can an Economic Adviser Do When the President Adopts Bad Economic Policies?"

"What Can An Economic Adviser Do When the President Adopts Bad Economic Policies?" Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel Professor, KSG, Harvard University The Pierson Lecture, Swarthmore, April 21, 2005 Summary: What would you do if you were appointed Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under a president who was committed to one or more specific policies that you considered to be inconsistent with good economics? A look at the experiences of your predecessors over the last 40 years might help illustrate your alternative options. The lecture will review the history. It will then go on to suggest that such conflicts should be particularly acute in the current Administration. The reason is that Republican presidents have increasingly adopted policies-- with regard particularly to budget deficits, trade, the size of government, and inflation -- that deviate from the principles of good economics, and that used to be considered the weaknesses of Democratic presidents. It is a great honor to be giving the Pierson lecture.1 I must confess that I never had Frank Pierson for a course. But he was the senior eminence of the Economics Department when I attended Swarthmore in the early 1970s, having already been associated with the department more than 40 years. In that time, Frank Pierson was known as one of the last professors who still regularly held his honors seminars at his house, with an impressive series of desserts, including make-your-own sundaes, and Irish coffee. The early 1970s were a volatile time of course, with the War in Viet Nam still on.2 In 1972 the big split on campus was between those of us working for McGovern on the left, and the 1 The author wishes to acknowledge help from Peter Jaquette, Arnold Kling, Jeff Miron, Stephen O’Connell, Francis Bator, Michael Boskin, David Cutler, Jason Furman, Gilbert Heebner, William Gale, Jeff Liebman, Peter Orszag, Roger Porter, Charles Schultze, Phillip Swagel, Laura Tyson, Murray Weidenbaum, Marina Whitman, and Janet Yellen. -

The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America 1

More The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America ROBERT M. COLLINS 1 2000 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2000 Published by Oxford All rights reserved. No by Robert M. University Press, Inc. part of this publication Collins 198 Madison Avenue, may be reproduced, New York, New York stored in a retrieval 10016. system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, Oxford is a registered mechanical, trademark of Oxford photocopying, recording, University Press. or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging–in–Publication Data Collins, Robert M. More : the politics of economic growth in postwar America / Robert M. Collins. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–19–504646–3 1. Wealth—United States—History—20th century. 2. United States—Economic policy. 3. United States—Economic conditions—1945–. 4. Liberalism—United States— History—20th Century. 5. National characteristics, American. I. Title. HC110.W4C65 2000 338.973—dc21 99–022524 Design by Adam B. Bohannon 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For My Parents Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Prologue: The Ambiguity of New Deal Economics 1 1 > The Emergence of Economic Growthmanship 17 2 > The Ascendancy of Growth Liberalism 40 3 > Growth Liberalism Comes a Cropper, 1968 68 4 > Richard Nixon’s Whig Growthmanship 98 5 > The Retreat from Growth in the 1970s 132 6 > The Reagan Revolution and Antistatist Growthmanship 166 7 > Slow Drilling in Hard Boards 214 Conclusion 233 Notes 241 Index 285 Preface bit of personal serendipity nearly three decades ago inspired this A book. -

Unemployment Crisis

UNEMPLOYMENT CRISIS HEARING BEFORE THE JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE CONGRESS 01 THE UNITED STATES NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION DECEMBER 9, 1982 Printed for the use of the Joint Economic Committee U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 18-593 O WASHINGTON : 1983 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE (Created pursuant to sec. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th Cong.) HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SENATE HENRY S. REUSS, Wisconsin, Chairman ROGER W. JEPSEN, Iowa, Vice Chairman RICHARD BOLLING, Missouri WILLIAM V. ROTH, J r ., Delaware LEE H. HAMILTON, Indiana JAMES ABDNOR, South Dakota GILLIS W. LONG, Louisiana STEVEN D. SYMMS, Idaho PARREN J. MITCHELL, Maryland PAULA HAWKINS, Florida AUGUSTUS F. HAWKINS, California MACK MATTINGLY, Georgia CLARENCE J. BROWN, Ohio LLOYD BENTSEN, Texas MARGARET M. HECKLER, Massachusetts WILLIAM PROXMIRE, Wisconsin JOHN H. ROUSSELOT, California EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts CHALMERS P.WYLIE, Ohio PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland J a m e s K. Galbraith, Executive Director Bruch II. B artlett, Deputy Director (II) Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis CONTENTS WITNESS AND STATEMENTS T h u r s d a y , D e c e m b e r 9, 1982 Jepsen, Hon. Roger W., vice chairman of the Joint Economic Committee: Page Opening statement- _____ ________________ _____ _______ ___ 1 Reuss, Hon. Henry S., chairman of the Joint Economic Committee: Open ing statement------------------------- _ ----------------- ------------- ----- <MC0 Feldstein, Hon. Martin S.. Chairman, Councl of Economic Advisers— SUBMISSION FOR THE RECORD T h u r s d a y , D e c e m b e r 9, 1982 Brown, Hon. -

The Pros and Cons of Globalization

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Special 7 1-1-2001 The Pros and Cons of Globalization Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Robert Batterson Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L. and Batterson, Robert, "The Pros and Cons of Globalization", Special 7, 2001, doi:10.7936/K71C1V2Z. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/175. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. II II II IJ. II II II THE PROS AND CONS OF GLOBALIZATION by Robert Batterson and Murray Weidenbaum January 2001 Center for the Study of American Business CS18 Washington University in St. Louis ( .. About the Authors '·Robert Batterson Robert Batterson is the communications director at the Center for the Study ofAmerican Business at Washington University. He has been with the Center since 1992 and serves as the primary public affairs officer to the national media, government, business, academia, and the public at large. He has also served as managing editor and director ofCSAB publications. He is coeditor and coauthor (with Kenneth Chilton and Murray Weidenbaum) of The Dynamic American Firm (Boston: K.luwer Publishers, 1996). His research interests include international trade, global competition, and international affairs. He has written numerous articles on international trade issues that have been published in newspapers including the Journal ofCommerce, Investors Business Dail~ Miami Herald, Houston Chronicle, San Diego Union-Tribune, St. -

Down Market Battle Plan

The Shape of Recovery: What’s Next? Panelists Leon LaBrecque Matt Pullar JD, CPA, CFP®, CFA Vice President, Private Client Chief Growth Officer Services 248.918.5905 216.774.1192 [email protected] [email protected] 2 As an independent financial services firm, our About Sequoia salaried, non-commission professionals have Financial Group access to a variety of solutions and resources and our recommendations are based solely on what works best for you, not us. 3 1. What are we monitoring? 2. What are we hearing from our Financial investment partners? Market Update 3. What are we recommending? 4 COVID-19: U.S. Confirmed Cases and Fatalities S o urce: Johns Hopkins CSSE, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Guide to the Markets – U.S. Data are as of June 30, 2020. 5 Consumer Sentiment Index S o urce: CONSSENT Index (University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index) Copyright 2020 Bloomberg Finance L.P. 17-Jul-2020 6 COVID-19: Fatalities S o urce – New York Times https://static01.nyt.com/images/2020/0 7/20/multimedia/20-MORNING- 7DAYDEATHS/20-MORNING- 7DAYDEATHS-articleLarge.png 7 High-Frequency Economic Activity S o urce: Apple Inc., FlightRadar24, Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA), OpenTable, STR, Transportation Security Administration (TSA), J.P. Morgan Asset Management. *Driving directions and total global flights are 7- day moving averages and are compared to a pre-pandemic baseline. Guide to the Markets – U.S. Data are as of June 30, 2020. 8 S&P 500 Index at Inflection Points S o urce: Compustat, FactSet, Federal Reserve, Standard & Poor’s, J.P. -

American Economic Policy in the 1980S: a Personal View

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: American Economic Policy in the 1980s Volume Author/Editor: Martin Feldstein, ed. Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-24093-2 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/feld94-1 Conference Date: October 17-20, 1990 Publication Date: January 1994 Chapter Title: American Economic Policy in the 1980s: A Personal View Chapter Author: Martin S. Feldstein Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c7752 Chapter pages in book: (p. 1 - 80) American Economic 1 Policy in the 1980s: A Personal View Martin Feldstein The decade of the 1980s was a time of fundamental changes in American eco- nomic policy. These changes were influenced by the economic conditions that prevailed as the decade began, by the style and political philosophy of F’resi- dent Ronald Reagan, and by the new intellectual climate among economists and policy officials. The unusually high rate of inflation in the late 1970s and the rapid increase of personal taxes and government spending in the 1960s and 1970s had caused widespread public discontent. Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 reflected this political mood and provided a president who was commit- ted to achieving low inflation, to lowering tax rates, and to shrinking the role of government in the economy. In our democracy, major changes in government policy generally do not occur without corresponding changes in the thinking of politicians, journalists, other opinion leaders, and the public at large. In the field of economic policy, those changes in thinking often reflect prior intellectual developments within the economics profession itself. -

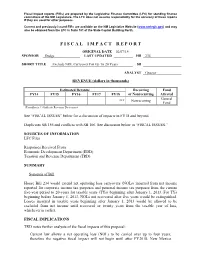

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current and previously issued FIRs are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov) and may also be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/14 SPONSOR Dodge LAST UPDATED HB 234 SHORT TITLE Exclude NOL Carryover For Up To 20 Years SB ANALYST Graeser REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Estimated Revenue Recurring Fund FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 or Nonrecurring Affected General *** Nonrecurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decreases) See “FISCAL ISSUES” below for a discussion of impacts in FY18 and beyond. Duplicates SB 156 and conflicts with SB 106. See discussion below in “FISCAL ISSUES.” SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Economic Development Department (EDD) Taxation and Revenue Department (TRD) SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 234 would extend net operating loss carryovers (NOLs) incurred from net income reported for corporate income tax purposes and personal income tax purposes from the current five-year period to 20-years for taxable years (TYs) beginning after January 1, 2013. For TYs beginning before January 1, 2013, NOLs not recovered after five years would be extinguished. Losses incurred in taxable years beginning after January 1, 2013 would be allowed to be excluded from net income until recovered or twenty years from the taxable year of loss, whichever is earlier. -

Simon Kuznets and the Empirical Tradition in Economics

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Political Arithmetic: Simon Kuznets and the Empirical Tradition in Economics Volume Author/Editor: Robert William Fogel, Enid M. Fogel, Mark Guglielmo, and Nathaniel Grotte Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-25661-8, 978-0-226-25661-0 (cloth) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/foge12-1 Conference Date: n/a Publication Date: March 2013 Chapter Title: The Emergence of National Income Accounting as a Tool of Economic Policy Chapter Author(s): Robert William Fogel, Enid M. Fogel, Mark Guglielmo, Nathaniel Grotte Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12915 Chapter pages in book: (p. 49 - 64) 3 :: The Emergence of National Income Accounting as a Tool of Economic Policy Herbert Hoover was sworn in as president at the end of a decade of generally vigorous economic growth, marred by the deep but short recession of 1920–21. By March 1929, the economy was near the top of a vigorous boom. In his inaugural address, Hoover was lyrical in his vision of American prosperity: “Ours is a land rich in resources; stimulating in its glorious beauty; fi lled with millions of happy homes; blessed with comforts and opportunity. In no nation are the institu- tions of progress more advanced. In no nation are the fruits of accom- plishment more secure. In no nation is the government more worthy of respect. No country is more loved by its people. I have an abiding faith in their capacity, integrity, and high purpose. -

Grading Our Policymakers

A SYMPOSIUM OF VIEWS THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICY 888 16th Street, N.W., Suite 740 Washington, D.C. 20006 Phone: 202-861-0791 • Fax: 202-861-0790 www.international-economy.com How effectively have they dealt Grading with the root causes of the Our Great Financial Crisis? Policymakers lame for the Great Financial Crisis assets on their balance sheets even as they can be laid on many causes. Some increased their use of financial leverage to Bargue that the crisis stemmed from dangerous levels. Then there was the severe global savings imbalances that led alleged politicizing in the United States of to the under-pricing of financial risk. The Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. United States consumed too much and Some attribute the crisis to an overly saved too little, while large parts of the accommodative monetary policy. The world became dangerously export- breakdown of Glass-Steagall and the dependent. growth of “too big to fail” institutions, Others attribute the crisis to a lack of which were able to engage in reckless transparency in the asset-backed securities financial risk-taking using taxpayers as markets. Observers have cited the bank their safety net, is also faulted. regulators and credit rating agencies for To what extent have our policy leaders being asleep at the switch, along with the addressed these and other causes to pre- banks’ inability to value the sophisticated vent future crises? Two dozen experts offer their views. 20 THE INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY SPRING 2010 An Incomplete. sparked the flames: the Fed’s exceptionally low interest rates in 2003–04 and the capital inflows into the United States associated with reserve accumulation abroad then poured additional fuel on the fire.