Adobe PDF Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camelot -.: Carton Collector

Mitos y Leyendas - Camelot (236) cartoncollector.cl 001 UR Draig Goch 081 R Levantar Muerto 161 V Paiste 002 UR Clídna 082 R Vampiro de Almas 162 V Dragón del Monte 003 UR Morgause 083 R Alas del Murciélago 163 V Blue Ben 004 UR Arthur Pendragón 084 R Regresar la Espada 164 V Serpopardo 005 UR Duelo de Dragón 085 R Coronación 165 V Glatisant 006 UR Seducción 086 R Excalibur Liberada 166 V Gwiber 007 UR Invocar Corrupción 087 R Torneo 167 V Rhydderch 008 UR Garra de Cristal 088 R Letanía del Rayo 168 V Tlachtga 009 MR Dragón Blanco 089 R Aura Bendita 169 V Ceasg 010 MR Gwyn ap Nudd 090 R Llamar a los Antiguos 170 V Lady Blanchefleur 011 MR Fuath 091 R Licántropos Rampantes 171 V Bugul Noz 012 MR Balin dos Espadas 092 R Yelmo Montadragón 172 V Gancanagh 013 MR Bridei I 093 R Hacha de los Bosques 173 V Guinevak 014 MR Incinerar 094 R Clarent 174 V John de la Costa 015 MR Relámpago Faérico 095 R Primera Excalibur 175 V Korrigan 016 MR Bendición de Armas 096 R Cementerio Dragón 176 V Addanc 017 MR Cortamundos 097 R Isla de Avalón 177 V Wight 018 MR Nido de Uolot 098 R Cementerio Impuro 178 V Cu Sith 019 M Dragón Inferno 099 R Guardia Gozosa 179 V Palamades 020 M Merlín Ambrosius 100 C Cockatriz 180 V Agravain 021 M Sir Perceval 101 C Wyvern Negro 181 V Gaheris 022 M Auberón 102 C Ave Boobrie 182 V Lucán 023 M Oilliphéist 103 C Stollenwurm 183 V Sir Héctor 024 M Lancelot del Lago 104 C Vouivre 184 V Mark de Cornwall 025 M Morgana de la Sombra 105 C Dragón de Dalry 185 V Olwen 026 M Claíomh Solais 106 C Roba Almas 186 V Pellinore 027 M Dullahan -

Leprechauns Are the Most Well-Known Elves (Fairies) of Ireland

Leprechauns are the most well-known elves (fairies) of Ireland. They live in the large green hills and in the forests of Furniture may be moved around the room, County Antrim. A leprechaun is an ugly and the whiskey or milk will be found to little creature with pointed ears. He have gone down overnight, and then to is about 40 centimetres tall. He likes have been replaced with water (especially being alone and avoids contact with the whiskey!). If all this begins to happen, humans or any other leprechauns or the family involved will know they must fairies. His job is to make shoes for the start leaving out presents of food and other fairies. Because they are a kind of drink to keep the cheeky little fairy happy. fairy, leprechauns are often invisible. Then, the leprechaun will go round the When they are not invisible, you can house at night finishing the jobs that the recognise a leprechaun because he has a people have no time to do. shoe in one hand and a hammer in the other. He also likes to smoke a pipe of Leprechauns guard the fairies' treasures tobacco which smells horrible! as they must prevent humans from stealing it. They hide the treasures in a 4-leaf Leprechauns are naughty, they like to shamrock garden called Lucky Charm cause mischief. They like to hide in garden. According to myth, Leprechauns trees and although they are small, they hate the rainbow, because it will show can usually move very fast and are nearly where the gold is hidden. -

Chaotic Descriptor Table

Castle Oldskull Supplement CDT1: Chaotic Descriptor Table These ideas would require a few hours’ the players back to the temple of the more development to become truly useful, serpent people, I decide that she has some but I like the direction that things are going backstory. She’s an old jester-bard so I’d probably run with it. Maybe I’d even treasure hunter who got to the island by redesign dungeon level 4 to feature some magical means. This is simply because old gnome vaults and some deep gnome she’s so far from land and trade routes that lore too. I might even tie the whole it’s hard to justify any other reason for her situation to the gnome caves of C. S. Lewis, to be marooned here. She was captured by or the Nome King from L. Frank Baum’s the serpent people, who treated her as Ozma of Oz. Who knows? chattel, but she barely escaped. She’s delirious, trying to keep herself fed while she struggles to remember the command Example #13: word for her magical carpet. Malamhin of the Smooth Brow has some NPC in the Wilderness magical treasures, including a carpet of flying, a sword, some protection from serpents thingies (scrolls, amulets?) and a The PCs land on a deadly magical island of few other cool things. Talking to the PCs the serpent people, which they were meant and seeing their map will slowly bring her to explore years ago and the GM promptly back to her senses … and she wants forgot about it. -

Seeing Is Believing

0 6 M AY 1 9 9 8 Seeing is Believing How photography killed Victorian Fairy Painting When William Blake reported a fairy funeral in his back garden, it's doubtful anyone demanded proof of what he had seen. That, of course, was before the camera entered the picture. Photography attempted to make up for the supposed inability of previous generations to record visually what was 'really' there, by providing apparently objective evidence for manifestations that could otherwise only be supported on a subjective basis. Confusing art with a kind of faux-scientic journalism, one casualty of this somewhat misguided will-to-truth was the representation of fairies. Developments in photography demanded that fairies - symbolic remnants of a displaced people, fallen angels, heathen dead or the unconscious made esh - relocate from their niche in the imagination of folklorists, dramatists and artists, to science's inhospitable laboratory. It was a move that, as it inadvertently sanitised, de-sexualised and trivialised fairy mythology, revealed elements of truth and ction, and showed the boundaries between genres and media to be as layered and co-dependant as the pieces of a Russian Doll. 'I see only phantoms that strike my eye, but disappear as soon as I try to grasp them' wrote Jean Jacques Rousseau in 1769. 1 The diculty of grasping phantoms and the myriad motivations for wanting to do so have, over the centuries, been manifold. During no period in history, however, was the attempt made more vigorously than in Victorian Britain, where phantoms assumed wings and found their way into painting. -

Norse Mythology

^^^m,'^^^' Section .tP 231922 NORSE OB, THE RELIGION OF OUR FOREFATHERS, CONTAINING ALL THE MYTHS OF THE EDDAS, SYSTEMATIZED AND INTEEPEETED. AN INTRODUCTION, VOCABULARY AND INDEX. By E. B. ANDERSON, A.M., PROFESSOR OF THE SCANDINAVIAN LANGUAGES IN THE UNIVERSITY OP WISCONSIN, AUTHOR OP "AMERICA NOT DISCOVERED BY COLUMBUS," "den NORSKE MAALSAG," ETC. CHICAGO: S. C. GKIGGS AND COMPANY. LONDON. TRUBNER & CO. 1875. COPTKIGHT 1875. By 8. C, GRIGGS AND COMPANY. I KMIGHT St LEONARD I ELECTROTYPED BY A. ZEESE <tl CO. TO HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW, THE AMERICAN POET, WHO HAS NOT ONLY REFRESHED HIMSELF AT THE CASTALIAN FOUNTAIN, BUT ALSO COMMUNED WITH BRAGE, AND TAKEN DEEP DRAUGHTS FROM THE WELLS OF URD AND MIMER, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED, WITH THE GRATEFUl. REVERENCE OF THE AUTHOR. I think Scandinavian Paganism, to us here, is more interesting than any other. It is, for one thing, the latest ; it continued in these regions of Europe till the eleventh century : eight hundred years ago the Norwegians were still worshipers of Odin. It is interesting also as the creed of our fathers ; the men whose blood still runs in our veins, whom doubtless we still resemble in so many ways. Strange : they did believe that, while we believe so differently. Let us look a little at this poor Norse creed, for many reasons. We have tolerable means to do it ; for there is another point of interest in these Scandinavian mythologies : that they have been preserved so well. Neither is there no use in knowing something about this old Paganism of our fathers. Unconsciously, and combined with higher things, it is in us yet, that old faith withal. -

What Lies Beyond an Extended Bestiary for Beyond the Wall and Other Adventures by Colin Chapman

WHAT LIES BEYOND AN EXTENDED BESTIARY FOR BEYOND THE WAll AND OTHER ADVENTURES BY COLIN CHAPMAN Amphisbaena for cruelty and a curious nature. Though not physically A venomous desert-dwelling reptile, the amphisbaena strong, their bites are paralyzing, and small bands of is a large serpent with a head at each end of its sinuous these beings delight in observing and tormenting all body, allowing it to swiftly move in either direction or they encounter. attack with a pair of bites. Its lambent green eyes attract insects to it during the hours of darkness, these being Hit Dice: 1d6 (4 HP) its preferred prey, though it will aggressively protect AC: 15 itself from anything it deems a threat. Attack: +1 to hit, 1d4 damage + poison (bite) Alignment: Chaotic Hit Dice: 2d4 (5 HP) XP: 15 AC: 13 Notes: Poisonous (anyone bitten by a attorcroppe Attack: +2 to hit, 1d6 damage + poison (bite) must make a saving throw versus poison or be para- Alignment: Neutral lyzed for 1d4 hours), True Name (attorcroppes have XP: 60 true names which give their foes power over them), Notes: Poisonous (anyone bitten by an amphisbaena Vulnerable to Iron (attorcroppes take double damage must make a saving throw versus poison or suffer an from iron) immediate extra 2 damage), Two-Headed (the amphis- baena may make two bite attacks per round) Black Dog Large faerie hounds with coats the color of coal and Animated Statue eyes that glimmer red, black dogs silently prowl the Animated via sorcerous means, statues serve as the night, haunting old roads and pathways, running with ideal guardians, ever-vigilant, unmoving, and unrecog- the Wild Hunt, and howling at stormy skies. -

Heroes, Gods and Monsters of Celtic Mythology Ebook

HEROES, GODS AND MONSTERS OF CELTIC MYTHOLOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Fiona Macdonald,Eoin Coveney | 192 pages | 01 May 2009 | SALARIYA BOOK COMPANY LTD | 9781905638970 | English | Brighton, United Kingdom Heroes, Gods and Monsters of Celtic Mythology PDF Book This book is not yet featured on Listopia. The pursuit was a long one, and Caorthannach knew St. Danu DAH-noo. Details if other :. Co Kerry icon Fungie the Dolphin spotted after fears he was dead. The pair is said to whip the horses with a human spinal cord. Though the saint was desperately thirsty, he refused to drink from the poisoned wells and prayed for guidance. Scota SKO-tah. Showing The Dullahan rides a headless black horse with flaming eyes, carrying his head under one arm. He is said to have invented the early Irish alphabet called Ogham. Patrick when he banished the snakes out of Ireland. Cancel Reply. One monster, however, managed to escape — Caorthannach, the fire-spitter. Comments Show Comments. Carman is the Celtic goddess of evil magic. Leanan Sidhe would then take her dead lovers back to her lair. Ancient site of Irish Kings and the Tuatha de Danann. Now the Fomori have returned to their waters and transformed into sea monsters who prey on humans. Bay KIL-a. Patrick would need water to quench his thirst along the way, so she spitfire as she fled, and poisoned every well she passed. Several of the digital paintings or renderings for each of the archetypes expressed by various artists. According to Irish folklore, Sluagh are dead sinners that come back as malicious spirits. -

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1 Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by William Butler Yeats This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry Author: William Butler Yeats Editor: William Butler Yeats Release Date: October 28, 2010 [EBook #33887] Language: English Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAIRY AND FOLK TALES *** Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Brian Foley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) FAIRY AND FOLK TALES OF THE IRISH PEASANTRY. EDITED AND SELECTED BY W. B. YEATS. THE WALTER SCOTT PUBLISHING CO., LTD. LONDON AND FELLING-ON-TYNE. NEW YORK: 3 EAST 14TH STREET. INSCRIBED TO MY MYSTICAL FRIEND, G. R. CONTENTS. THE TROOPING FAIRIES-- PAGE The Fairies 3 Frank Martin and the Fairies 5 The Priest's Supper 9 The Fairy Well of Lagnanay 13 Teig O'Kane and the Corpse 16 Paddy Corcoran's Wife 31 Cusheen Loo 33 The White Trout; A Legend of Cong 35 The Fairy Thorn 38 The Legend of Knockgrafton 40 A Donegal Fairy 46 CHANGELINGS-- The Brewery of Egg-shells 48 The Fairy Nurse 51 Jamie Freel and the Young Lady 52 The Stolen Child 59 THE MERROW-- -

Fairy Queen Resource Pack

1 The Fairy Queen Resource Pack 2 Contents Page 3-4 Plot Summary 5 Characters: The Faeries 6 Characters: The Lovers 7 Characters: The Mechanicals 8-9 Henry Purcell & The Fairy Queen 10 Creative Writing Exercise: Mischievous Puck 11 Drama Exercise: You Spotted Snakes 12-13 Design and make a Fairy Crown 14 Magical Muddle character game 15 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Word Search 3 “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” by William Shakespeare Plot Summary Duke Theseus and Queen Hippolyta are preparing for their wedding. Egeus, a nobleman, brings his daughter Hermia to Theseus, as he wants her to marry Demetrius but she is in love with another man, Lysander. The Duke, Theseus, commands Hermia to obey her father and either marry Demetrius or, according to Athenian Law, she must be put to death or enter a convent. Hermia and Lysander decide to runaway together that night to get married in secret. Hermia tells her best friend Helena of her plans. Helena is in love with Demetrius (even though he hates her and loves Hermia), so she tells him about Hermia and Lysander’s plans, hoping that she might win his love. All the four lovers run away into the woods that night - Demetrius following Hermia & Lysander and Helena following after Demetrius. Meanwhile, there are a group of tradespeople called the Mechanicals who are rehearsing a play in the same woods. They include Bottom the weaver, Quince the taylor and Flute the bellows mender, among others. The play they are rehearsing is ‘The Tragedy of Pyramus and Thisbe’ and it is to be performed for the Duke and Queen at their wedding. -

Three Irish Legends

Read and listen. Three Irish Legends The Leprechaun Leprechauns, also known as ‘the little folk’, are very likeable and reflect the wonderful Irish sense of fun. Legend says that every leprechaun has a pot of gold which he must give to anyone who can catch him. But leprechauns are very clever and quick so there’s not much chance that you’ll be able to catch one! There are countless stories about leprechauns, like this one. A man was walking through a forest one day when a leprechaun jumped out in front of him. The man managed to grab him and he made the leprechaun take him to where his treasure was hidden. The man didn’t have a spade with him so he couldn’t dig it up, but he tied a red handkerchief to a bush so he could find it again. He went to get his spade but when he came back he couldn’t find the treasure, because there was a red handkerchief tied to every bush in the forest! New Horizons Digital 2 • Unit 5 pp.48–49 © Oxford University Press PHOTOCOPIABLE The Banshee Banshee is Irish (the language of Ireland) for fairy woman. If you hear the frightening crying of the banshee at night, it means that someone close to you has died. They say that sometimes she’s a mysterious white figure with long silver hair and a grey cloak. She’s tall and thin and her face is pale with eyes which are red from crying. At other times she’s able to appear as a lovely young girl with long red hair. -

Opportunities in Scots Independence Movement • Breton Cultural Forces Tarred • Cilmeri Rally Reclaimed • Call for Nati

No. 125 Spring 2004 €3.00 Stg£2.50 • Opportunities in Scots Independence Movement • Breton Cultural Forces Tarred • Cilmeri Rally Reclaimed • Call for National Plan for Irish • Environmental Rights Campaign in Cornwall • Manx in Court • Un Tele Breizhat evit an Holl ALBA: C O M A N N CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANN1N: COMMEEYS CELTIAGH 62 r Fuadach nan Gaidheal Gura mise titrsach. A ' caoidh cor na ditthcha, A lbo <3 Bha cliuiteach is treun; Rinn uachdrain am fuadach IL _l Gu fada null thar chuuntan. Am fearann chaidh thoirt uapa 'S thoirt suas do na feidli. AR BÀRDACHD "...agus eaoraich cuideachd!" arsa sinne. amt an ceithir duanairean Tha na tri leabhraichean seo ri lhaotainn bho GÀIR NAN CLÀRSACH...tliagh Culm Ó An targainteachd dhùainn - - Birlinn Ltd. West Newington House. 10 Baoill sco agus dh'eadar-theangaich Meg Bras meanmnach Fir Alba Newington Road. Dim Eideann EH9 IQS. no Bateman e. Tlia dà fhichead is tri dàin Le' n armaibh air thùs an leabhar-reiceadair agaibh. Gàidhlig ami eadar na bliadlinachan I 600 gu Nuair a dh'eires gach treunlaoch 1648. Cha d'rinn neach an aon rud riamh. Le-n èideadh glan ùr. AN TU IL... dheasaich Raghnall Mac ille Dliuibh an leahhar seo agus dh’ fhoillsich Sco agaiblt linn gaisgeil nuair a bha an ceann ... Gur rrtairg nàmhaid a tharladh Polygon. 22 George Square. Diin Eideann e. einnidh ann an talla aige: far an robh na ledis Ri ànriainn ino rùin; Seo agaibh Duanaire Gtiidhlig an 20mh no torches a" nochdadh an Inchdleannihainn Ceud. -

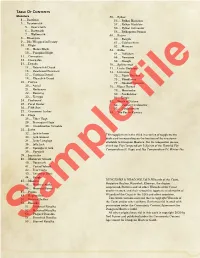

Table of Contents Monsters 56

Table Of Contents Monsters 56 . Rylkar 4 . Banshrae 56 . Rylkar Harridan 5 . Beastwraith 57 . Rylkar Madclaw 5 . Deerwraith 58 . Rylkar Tormentor 6 . Ratwraith 58 . Rylkspawn Swarm 7 . Wolfwraith 60 . Satyrs 8 . Bhaergala 60 . Bargda 9 . Bile Wrapped in Beauty 61 . Gabharchinn 10 . Blight 62 . Marsyan 10 . Melon Blight 64 . Sidhe 10 . Pumpkin Blight 64 . Dullahan 11 . Corrupture 66 . Nemanon 12 . Dearg-due 68 . Sluagh 14 . Dryads 70 . Splinterwaif 14 . Briarwitch Dryad 71 . Uncle Skeleton 16 . Deadwood Revenant 73 . Unicorns 17 . Gulthias Dryad 73 . Black Unicorn 18 . Rhyzalich Dryad 75 . Bloodlance 20 . Fairies 77 . Shadow Unicorn 20 . Aorial 79 . Water Horses 21 . Bevhensie 79 . Mourioche 22 . Boowray 80 . Nuckelavee 23 . Terropo 81. Tangie 24 . Fenhound 82 . Wrath of Nature 25 . Feral Yowler 82 . Calvary Creekrotter 26 . Filth Son 83 . Cinderswarm 27 . Gruesome Lurker 84 . The Fey in Ravnica 28 . Hags 28 . Elder Hags 29 . Termagant Hags 30 . Grandmother Griselda 32 . Jacks 32 . Jack-in-Irons This supplement is the third in a series of supplements 33 . Jack Around dedicated to expanding on the bestiary of fey creatures 34 . Jacky Longlegs available to Dungeon Masters. For its companion pieces, 36 . Jolly Jack check out Fey Compendium I: Spirits of the Feywild, Fey 37 . Springheel Jack Compendium II: Hags, and Fey Compendium IV: Winter Fey 38 . Spryjack 39 . Joystealer 40 . Mishocair Ghosts 40 . Bocanach 41 . Cariad Ysbryd 42 . Fear Gorta 43 . Lhiannan Shee 44 . Saugh 45 . Moonrat DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, 46 . Moonrat Alpha Forgotten Realms, Ravenloft, Eberron, the dragon 46 . Moonrat Baron ampersand, Ravnica and all other Wizards of the Coast 47 .