1 Strategic Transformations in the Media Abstract Digital Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013--Annual-Report-Accounts.Pdf

Helping people make measurable progress in their lives through learning ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2013 OUR TRANSFORMATION To find out more about how we are transforming our business go to page 09 EFFICACY To find out more about our focus on efficacy go to page 14 OUR PERFORMANCE For an in-depth analysis of our performance in 2013 go to page 19 Pearson is the world’s leading learning company, with 40,000 employees in more than 80 countries working to help people of all ages to make measurable progress in their lives through learning. We provide learning materials, technologies, assessments and services to teachers and students in order to help people everywhere aim higher and fulfil their true potential. We put the learner at the centre of everything we do. READ OUR REPORT ONLINE Learn more www.pearson.com/ar2013.html/ar2013.html To stay up to date wwithith PPearsonearson throughout the year,r, visit ouourr blog at blog.pearson.comn.com and follow us on Twitteritter – @pearsonplc 01 Heading one OVERVIEW Overview 02 Financial highlights A summary of who we are and what 04 Chairman’s introduction 1 we do, including performance highlights, 06 Our business models our business strategy and key areas of 09 Chief executive’s strategic overview investment and focus. 14 Pearson’s commitment to efficacy OUR PERFORMANCE OUR Our performance 19 Our performance An in-depth analysis of how we 20 Outlook 2014 2 performed in 2013, the outlook 23 Education: North America, International, Professional for 2014 and the principal risks and 32 Financial Times Group uncertainties affecting our businesses. -

Governance Report

46 Pearson plc Annual report and accounts 2011 Board of directors Pearson’s 12-member board brings a wide range of experience, skills and backgrounds. Chairman Executive directors Glen Moreno Chairman Marjorie Scardino Chief executive Will Ethridge Chief executive, aged 68, appointed 1 October 2005 aged 65, appointed 1 January 1997 Pearson North American Education aged 60, appointed 1 May 2008 Chairman of the nomination committee Member of the nomination committee and member of the remuneration Will has three decades of experience committee Marjorie brings a range of business, legal in education and educational publishing, and publishing experience to Pearson. including nearly a decade and a half at Glen has more than three decades Before becoming Pearson CEO, she was Pearson where he formerly headed of experience in business and finance, chief executive of The Economist Group. our Higher Education, International and is currently deputy chairman of The Trained as a lawyer, she was a partner in and Professional Publishing business. Financial Reporting Council Limited in a Savannah, Georgia, law firm and at the Prior to joining Pearson in 1998, Will the UK, deputy chairman and senior same time founded with her husband the was a senior executive at Prentice Hall independent director at Lloyds Banking Pulitzer Prize-winning Georgia Gazette and Addison Wesley, and before that Group plc, and non-executive director newspaper. Marjorie is a director of an editor at Little, Brown and Co where of Fidelity International Limited. Nokia Corporation and on the non-profit he published in the fields of economics Previously, Glen was senior independent boards of Oxfam and the MacArthur and politics. -

Oliver, JJ (2018). Strategic Transformations in the Media

Published as: Oliver, J.J. (2018). Strategic Transformations in the Media. Journal of Media Business Studies, Volume 15, Issue 2, 1-22 Introduction Transformation: a marked change in form, nature, or appearance. It is a word that characterises the profound impact that digitalisation and new media technologies have had on the way that many media firms have managed their business. Whilst many media organisations have been exposed to continual levels of turbulence in the past 20 years, two critical events have acted as key drivers of transformational change. The emergence of widespread digitalisation in 1997 and new media technologies, circa 2003, are significant events that have acted as catalysts for technological innovation and market disruption. These high velocity environmental conditions have largely persisted since the late 1990s, and when viewed over the long term, provide an ideal context through which to examine corporate strategy, dynamic capabilities, corporate performance and the strategic transformation of media firms. These disruptive forces have also shaped and contextualised the theoretical debate of many media management researchers, so much so, that we are now seeing the emergence of ‘strategic’ media management as a topic of inquiry. The primary strands of this theme include: an examination of how a highly uncertain media environment has influenced management strategies, business models and profitability (Kung 2007; Koch, 2008; Doyle, 2013; Oliver, 2013; Horst and Jarventie-Thesleff, 2016; Kunz, Siebert and Mütterlein, 2016; Vukanovic, 2016; Daidj, 2018; Evens, Raats & von Rimscha, 2018; Horst, Murschetz, Brennan and Friedrichsen, 2018 ); how legacy media firms are developing dynamic capabilities in response to a fast changing media environment (Oliver, 2014; Naldi, Wikström and von Rimscha, 2014; Horst and Moisander, 2015; Hasenpusch and Baumann, 2017; and Maijanen and Virta, 2017); and how a strategy-as-practice approach has explicated the practical challenges of managing media organisations and their strategic 1 Published as: Oliver, J.J. -

Universidade De Santiago De Compostela

DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIAS DA COMUNICACIÓN UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA FACULTADE DE CIENCIAS DA COMUNICACIÓN Estratexias de pago por contidos e modelos de negocio da prensa dixital. Análise de caso do Financial Times, The Times e El Mundo en Orbyt Paid content strategies and business models of online newspapers. Case analysis of Financial Times, The Times and El Mundo in Orbyt Manuel Goyanes Martínez TESE DE DOUTORAMENTO presentada en DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIAS DA COMUNICACIÓN Director: Francisco Campos Freire Santiago de Compostela, 2013 PRESENTACIÓN Cal é o futuro da prensa, entendida coma un soporte de información e un medio de comunicación profesional organizado mediante unha estrutura empresarial e comercial? Esta é unha pregunta que tanto os profesionais da industria como os académicos se formulan dende a popularización de Internet como xanela de consumo informativo. No epicentro da cuestión está a revisión, reformulación ou fortalecemento do modelo de negocio, como base para o sostemento da organización e para a viabilidade do xornalismo de calidade no espazo dixital. Precisamente, achegar un pouco de luz sobre ese debate é un dos principais obxectivos da presente tese. Pero non o único. A través da análise en profundidade dos modelos de tres xornais (The Times, Financial Times e El Mundo en Orbyt), con estratexias de pago por contidos, tentamos contribuír de modo teórico e práctico á literatura existente. A gratuidade informativa a través do sistema de ingresos publicitario amosouse relativamente deficiente na maior parte de casos, polo que é necesario que a industria inicie a exploración e ensaio de novos modelos de negocio baseados na combinación do pago do lector e no recurso publicitario. -

Formal Minutes

House of Commons Treasury Committee Formal Minutes Session 2008–09 Treasury Committee: Formal Minutes 2008–09 1 Proceedings of the Committee Thursday 4 December 2008 John McFall, in the Chair Nick Ainger Ms Sally Keeble Mr Graham Brady Mr Andrew Love Jim Cousins Mr Mark Todd Mr Stephen Crabb Sir Peter Viggers Mr Michael Fallon 1. New Member Mr Stephen Crabb disclosed his interests, pursuant to the resolution of the House of 13 July 2002. For details of declaration of interests, see appendix 1. 2. Specialist Advisers (declaration of interests) The interests of the following specialist advisers were disclosed: Mr Roger Bootle, Professor David Heald, Professor David Miles, Professor Anton Muscatelli, Ms Bridget Rosewell, Professor Colin Talbot and Professor Geoffrey Wood. For details of declaration of interests, see appendix 2. 3. The Committee’s programme of work The Committee considered this matter. 4. Pre-Budget Report 2008 Ordered, That the following written evidence relating to the Pre-Budget Report 2008 be reported to the House for publication on the internet: Child Poverty Action Group, ACCA, Association of Friendly Societies, Professor David Heald, Professor Colin Talbot, John Whiting, and the New Policy Institute. Mr Robert Chote, Director, Institute for Fiscal Studies; Mr Roger Bootle, Managing Director, Capital Economics; Mr Simon Kirby, Research Fellow, National Institute of Economic and Social Research; Professor Colin Talbot, Professor of Public Policy and Management, Manchester Business School and Mr John Whiting, PwC and Low Incomes Tax Reform Group (LITRG), gave oral evidence. Mr Mike Brewer, Director, Institute for Fiscal Studies, Ms Teresa Perchard, Director of Public Policy, Citizens Advice, Mr Mervyn Kohler, Head of Public Affairs, Help the Aged, Mr Peter Kenway, Director, New Policy Institute, and Mr John Whiting, PwC and Low Incomes Tax Reform Group (LITRG), gave oral evidence. -

PEARSON FUNDING FIVE PLC €500,000,000 in Aggregate Principal Amount of 1.375% Guaranteed Notes Due 2025 Guaranteed by Pearson Plc Issue Price: 99.926 Per Cent

PEARSON FUNDING FIVE PLC €500,000,000 in aggregate principal amount of 1.375% Guaranteed Notes due 2025 Guaranteed by Pearson plc Issue price: 99.926 per cent. Pearson Funding Five plc (the “Issuer”) will pay interest annually on each 6 May, commencing 6 May 2016, up to the date of maturity or earlier upon redemption of the 1.375% Guaranteed Notes due 2025 (the “Notes”). The Issuer will be entitled to redeem the Notes in whole or in part at any time prior to their maturity at redemption prices to be determined using the procedures described in this prospectus. The Issuer will be entitled to redeem the Notes, in whole, but not in part, at 100% of their principal amount, plus accrued and unpaid interest to, but excluding, the date of redemption and any additional amounts upon the occurrence of certain tax events. Pearson plc (the “Guarantor” or “Pearson”) will fully, irrevocably and unconditionally guarantee all amounts payable under the Notes. The Notes will mature on 6 May 2025. The Notes and the related guarantees will rank pari passu with, respectively, all of the Issuer’s and the Guarantor’s other unsecured and unsubordinated debt. This prospectus constitutes a “prospectus” for the purposes of the Directive 2003/71/EC, as amended by Directive 2010/73/EU (the “Prospectus Directive”). Application has been made to the Financial Conduct Authority (the “FCA”) in its capacity as competent authority under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, as amended (“FSMA”) (the “U.K. Listing Authority”) for the Notes to be admitted to the Official List of the U.K. -

![[ "Printmgr File" ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7259/printmgr-file-5127259.webp)

[ "Printmgr File" ]

AS FILED WITH THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION ON March 22, 2013 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 or È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2012 or ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 for the transition period from to or ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report Commission file number 1-16055 PEARSON PLC (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) England and Wales (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 80 Strand London, England WC2R 0RL (Address of principal executive offices) Stephen Jones Telephone: +44 20 7010 2000 Fax: +44 20 7010 6060 80 Strand London, England WC2R 0RL (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile Number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered *Ordinary Shares, 25p par value New York Stock Exchange American Depositary Shares, each New York Stock Exchange Representing One Ordinary Share, 25p per Ordinary Share * Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the SEC. Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock at the close of the period covered by the annual report: Ordinary Shares, 25p par value ........................................ -

40XX VM Notice of Meeting.Indd

NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING The 2015 Annual General Meeting of Virgin Money Holdings (UK) plc will be held at the offi ces of FTI Consulting, 200 Aldersgate, Aldersgate Street, London EC1A 4HD on Friday, 1 May 2015 at 14:00 Virgin Money Fireworks Concert 2014. The concert is held each year to celebrate the end of the Edinburgh International Festival. Everyone’s better off Important information: This document is important and requires your immediate attention. If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of the proposals referred to in this document or as to the action you should take, you should immediately seek your own advice from a stockbroker, solicitor, accountant, or other independent professional adviser duly authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all of your shares, please send this document, together with the accompanying documents, as soon as possible to the purchaser or transferee, or to the stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was eff ected for delivery to the purchaser or transferee. Notice of Annual General Meeting 2015 Letter from the Chairman of Virgin Money Holdings (UK) plc Remuneration There are two resolutions proposed to shareholders on remuneration matters. The first is an advisory vote on the Directors’ Remuneration Report for the financial year ended 31 December 2014 (excluding the Directors’ Remuneration Policy), which covers the implementation of the remuneration policy during the period. The second is a binding Sir David Clementi vote on the Directors’ Remuneration Policy, which is intended to take Chairman effect from the conclusion of the AGM. -

An Analysis of U.S. History Textbooks: the Treatment of Primary Sources

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2009 An analysis of U.S. history textbooks: The treatment of primary sources Misty D. Rodeheaver West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rodeheaver, Misty D., "An analysis of U.S. history textbooks: The treatment of primary sources" (2009). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4521. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4521 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF U.S. HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: THE TREATMENT OF PRIMARY SOURCES by Misty D. Rodeheaver Dissertation submitted to the College of Human Resources & Education at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Curriculum & Instruction Approved by Dr. Mary Haas, Committee Chairperson Dr. -

Evening Reception Hosted by Sir Martin Sorrell, CEO WPP at The

Evening reception hosted by Sir Martin Sorrell, CEO WPP at the British Museum Tuesday 19th March 2013 6.45pm – 9.30pm Working Together for Young People @edu_employers #inspiringthefuture About the Charity Education and Employers Taskforce The Taskforce is a small independent charity launched in October 2009. Its vision is “that every school and college has an effective partnership with employers to provide young people with the inspiration, motivation, knowledge, skills and opportunities they need to help them achieve their potential and so secure our national prosperity.” Our Partnership Board brings together the country’s leading education and employment organizations and Trustees are principally senior business leaders with an interest in education. The Taskforce has a team of seven staff. We are committed to working with partners to make impactful and relevant employer engagement the norm across the educational experiences of young people. An underlying principle of the charity is that it does not charge schools or colleges for services provided to them. Similarly, it doesn’t charge organisations that seek to offer their staff to volunteer. 1 Since our launch in October 2009 we have: brought together an unprecedented alliance of employers, education and government working together to make it considerably easier for partners, from the private, public and third sectors, to work together efficiently, effectively and strategically. produced the first comprehensive on-line guides for schools and for employers on working together: www.employers-guide.org -

Introduction Our Strategy Our Performance Our Impact on Society Governance Financial Statements 03 Ft.Com Penguin.Com Pearsoned.Com Education Education

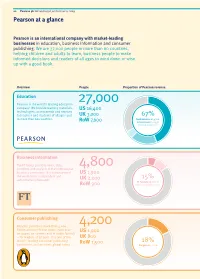

02 Pearson plc Annual report and accounts 2009 Pearson at a glance Pearson is an international company with market-leading businesses in education, business information and consumer publishing. We are 37,000 people in more than 60 countries, helping children and adults to learn, business people to make informed decisions and readers of all ages to wind down or wise up with a good book. Overview People Proportion of Pearson revenue Education 27,000 Pearson is the world’s leading education company. We provide learning materials, US 16,400 technologies, assessments and services to teachers and students of all ages and UK 3,000 67% in more than 60 countries. North America £2,470m RoW 7,600 International £1,035m Professional £275m Business information The FT Group provides news, data, 4,800 comment and analysis to the international business community. It is known around US 1,900 the world for its independent and 15% authoritative information. UK 2,000 FT Publishing £358m RoW 900 Interactive Data £484m Consumer publishing Penguin publishes more than 4,000 4,200 fiction and non-fiction books each year – US 1,900 on paper, on screens and in audio formats – for readers of all ages. It is one of the UK 800 world’s leading consumer publishing RoW 1,500 18% businesses and an iconic global brand. Penguin £1,002m Section 1 Introduction 03 i Learn more at Introduction www.pearson.com/aboutus Our strategy Businesses Markets We are a leading provider of educational For some years, Pearson has been material and learning technologies. a leader in education, with leading We provide test development, processing positions in large developed markets and scoring services to educational and local publishing centres in more institutions, corporations and professional than 30 countries. -

Form-20-F-Sec 6.Pdf

ACE BOWNE OF TORONTO 03/31/2010 06:24 NO MARKS NEXT PCN: 002.00.00.00 -- Page is valid, no graphics BOT U08539 001.00.00.00 12 AS FILED WITH THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION ON March 31, 2010 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 20-F (Mark One) n REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 or ¥ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009 or n TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 for the transition period from to or n SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report Commission file number 1-16055 PEARSON PLC (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) England and Wales (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 80 Strand London, England WC2R 0RL (Address of principal executive offices) Stephen Jones Telephone: +44 20 7010 2000 Fax: +44 20 7010 6060 80 Strand London, England WC2R 0RL (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile Number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered *Ordinary Shares, 25p par value New York Stock Exchange American Depositary Shares, each Representing One Ordinary Share, 25p per Ordinary Share New York Stock Exchange * Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the SEC.