Still Broken: New York State Legislative Reform 2008 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPL/Environmental Advocates

VOTERS’ GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 A quick look at the scores & find your legislators 4 EPL/Environmental Advocates is one of the first 2013 legislative wrap-up organizations in the nation formed to advocate for the future of a state’s environment and the health of its citizens. Through 6 lobbying, advocacy, coalition building, citizen education, and policy Oil slick award & development, EPL/Environmental Advocates has been New York’s honorable mention environmental conscience for more than 40 years. We work to ensure environmental laws are enforced, tough new measures are enacted, and the public is informed of — and participates in — important policy 8 Assembly scores by region debates. EPL/Environmental Advocates is a nonprofit corporation tax exempt under section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code. 18 Senate scores by region EPL/Environmental Advocates 22 353 Hamilton Street Bill summaries Albany, NY 12210 (518) 462-5526 www.eplscorecard.org 26 How scores are calculated & visit us online 27 What you can do & support us Awaiting action at time of print Signed into law How to read the Scorecard Rating Bill description SuperSuper Bills Bills Party & district Region 2013 Score 2012 Score New York SolarFracking Bill MoratoriumClimate &Protection HealthChild Impacts ActSafe ProductsCoralling Assessment Act Wild Boars Incentives for Energy StarShark Appliances Fin ProhibitionTransit Fund ProtectionPromoting LocalGreen Food Buildings Purchasing Extender 1 2 3 4 9 11 12 16 17 23 24 27 Governor Andrew M. Cuomo (D) ? ? S ? ? Eric Adams (D-20/Brooklyn) -

Rosendale Town Councilwoman Jen Metzger to Challenge State Senator Bonacic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 22, 2018 CONTACT: Kelleigh McKenzie, 845-518-7352 [email protected] Rosendale Town Councilwoman Jen Metzger to challenge State Senator Bonacic ROSENDALE, NY – Rosendale Town Councilwoman Jen Metzger is officially launching her campaign to challenge State Senator John Bonacic for New York’s 42nd District. Metzger said she understands first-hand the challenges faced by families in rural communities, and she is done waiting around for state senators to do their jobs. “We can only do so much at the local level,” said Metzger, a Democrat. “Fully funded schools, healthcare for all, and a clean energy economy that creates good local jobs will remain out of reach unless our state representatives are willing to fix New York’s broken tax system and pass legislation that helps working families. But year after year, they continue to serve the wealthy and well-connected at the expense of the rest of us.” Metzger has served more than a decade in local government and is also the Director of Citizens for Local Power, a non-profit organization working to transform energy policy and help communities transition to a more affordable, locally-based clean energy economy. Metzger has helped dozens of local governments across the political spectrum save energy and taxpayer dollars. She also led efforts to organize municipal leaders from Albany down through Orange County to oppose the Pilgrim Pipelines project, which would have carried millions of gallons of crude oil through rivers, aquifers, farms, and communities of the Hudson Valley every day. She is currently fighting for a reduction in Central Hudson’s customer charges, which are among the highest in the country. -

Voters' Guide

VOTERS’ GUIDE an insider’s guide2006 to the environmental records of New York State lawmakers EPL•Environmental Advocates EPL/Environmental Advocates EPL/Environmental Advocates was one of the first organizations in Board of Directors the nation formed to advocate for the Irvine Flinn, President future of a state’s environment and Laura Haight, Vice President the health of its citizens. Through Cara Lee, Secretary & Treasurer lobbying, advocacy, coalition Richard Allen building, citizen education and policy Richard Booth development, EPL/Environmental Eric A. Goldstein Lee Wasserman Advocates has been New York’s environmental conscience for Robert Moore, Executive Director almost 40 years. We work to ensure environmental laws are enforced, that tough new measures are enacted, and EPL/Environmental Advocates 353 Hamilton Street that the public is informed of, and Albany, NY 12210 participates in, important policy 518.462.5526 debates. EPL/Environmental www.eplvotersguide.org Advocates is a nonprofit corporation tax exempt under section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code. TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 LEGISLATIVE WRAP-UP 09 BILL SUMMARIES HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 14 ASSEMBLY SCORES 04 NEW LAWS 20 SENATE SCORES 05 BY THE NUMBERS 21 HOW SCORES ARE CALCULATED 06 PATAKI RETROSPECTIVE 22 WHAT YOU CAN DO 07 AWARDS 08 NYS BUDGET KILLED BILLS EPL•Environmental Advocates LEGISLATIVE WRAP-UP Big Bucks for the Environment, While State Senate Stymies Super Bill Success While the Governor and Legislature increased floor vote on a single Super Bill, despite the Environmental Protection Fund to $225 unprecedented bipartisan support in that house. million this year—no small feat—the State Senate made certain little else was But that’s how things work in Albany. -

2018 Proceeding Minutes.Pdf

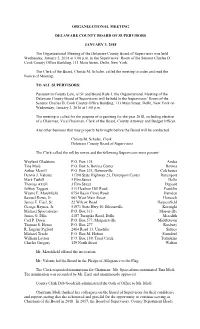

ORGANIZATIONAL MEETING DELAWARE COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS JANUARY 3, 2018 The Organizational Meeting of the Delaware County Board of Supervisors was held Wednesday, January 3, 2018 at 1:00 p.m. in the Supervisors’ Room of the Senator Charles D. Cook County Office Building, 111 Main Street, Delhi, New York. The Clerk of the Board, Christa M. Schafer, called the meeting to order and read the Notice of Meeting: TO ALL SUPERVISORS: Pursuant to County Law, §151 and Board Rule 1, the Organizational Meeting of the Delaware County Board of Supervisors will be held in the Supervisors’ Room of the Senator Charles D. Cook County Office Building, 111 Main Street, Delhi, New York on Wednesday, January 3, 2018 at 1:00 p.m. The meeting is called for the purpose of organizing for the year 2018, including election of a Chairman, Vice Chairman, Clerk of the Board, County Attorney and Budget Officer. Any other business that may properly be brought before the Board will be conducted. Christa M. Schafer, Clerk Delaware County Board of Supervisors The Clerk called the roll by towns and the following Supervisors were present: Wayland Gladstone P.O. Box 125 Andes Tina Molé P.O. Box 6, Bovina Center Bovina Arthur Merrill P.O. Box 321, Downsville Colchester Dennis J. Valente 11790 State Highway 23, Davenport Center Davenport Mark Tuthill 5 Elm Street Delhi Thomas Axtell 3 Elm Street Deposit Jeffrey Taggart 511 Heathen Hill Road Franklin Wayne E. Marshfield 6754 Basin Clove Road Hamden Samuel Rowe, Jr. 661 West Main Street Hancock James E. Eisel, Sr. -

Reshaping New York Report Page 1

Citizens Union of the City of New York November 2011 Reshaping New York Report Page 1 Appendix 1 1a. Nesting of New York City Assembly Districts in Senate Districts After 2002 Redistricting Cycle NESTING OF NEW YORK CITY’S ASSEMBLY DISTRICTS IN SENATE DISTRICTS Assembly Districts Number of Nested Senate District (By District Number) Assembly Districts 10 23, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 38 9 11 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 31, 33 8 12 30, 34, 36, 37, 38 5 13 34, 35, 37, 39 4 14 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33 7 15 23, 28, 30, 37, 38 5 16 22, 24, 25, 26, 27 5 17 40, 50, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 7 18 44, 50, 51, 52, 54, 55, 56, 57 8 19 40, 41, 42, 43, 55, 58, 59 7 20 42, 43, 44, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, 58 9 21 41, 42, 43, 44, 48, 51, 58, 59 8 22 41, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 59, 60 9 23 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 60, 61, 63 8 24 60, 61, 63, 62 4 25 50, 52, 57, 64, 66, 74 6 26 65, 67, 69, 73, 74, 75 6 27 41, 45, 47, 49, 44, 48 7 28 65, 68, 73, 84, 86 5 29 66, 67, 74, 75 4 30 67, 68, 69, 70 4 31 67, 69, 70, 71, 72, 78, 81 7 32 76, 79, 80, 82, 84, 85 6 33 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 86 6 34 76, 80, 82, 83 4 36 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 86 9 Appendix 1 ‐ 1 Citizens Union of the City of New York November 2011 Reshaping New York Report Page 2 1b. -

State Legislative Seats That Changed Party Control, 2018 - Ballotpedia

10/14/2019 State legislative seats that changed party control, 2018 - Ballotpedia View PDF - Start Here Free PDF Viewer - View PDF Files Instantly. Download ViewPDF Extension Now! OPEN ViewPDF.io State legislative seats that changed party control, 2018 PRIMARY ELECTIONS FEDERAL ELECTIONS STATE ELECTIONS LOCAL ELECTIONS VOTER INFORMATION On November 6, 2018, 6,073 seats were up for election across 87 of the nation's 99 state legislative chambers. As a result of the elections, control of 508 seats was flipped from one party to another. 2018 State Democrats gained a net 308 seats in the 2018 elections, Republicans lost a net 294 seats, and third legislative elections party and independent candidates lost a net 14 seats. At least one flip occurred in every state except Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Virginia, which did not hold state legislative elections in 2018. « 2017 2019 » New Hampshire had 77 seats flip, the most of any state. Sixty-seven of those seats flipped from Republicans to Democrats, seven from Democrats to Republicans, two from third party legislators to Republicans, and one from a third party legislator to a Democrat. Maine followed with 26 flips, including 16 Republican seats to Democrats, two Democratic seats to Republicans, three Republican seats to third party candidates, and five third party seats to Democrats. The only other state with more than 20 flips was Pennsylvania, with 19 Republican seats flipping to Democrats and three Democratic seats flipping to Republicans. Six state legislative chambers flipped control in 2018, including both chambers of the New Hampshire General Court, the state senates of Colorado, Maine, and New York, and the Minnesota House of Representatives. -

March 22, 2018 the Honorable John Flanagan the Honorable Carl

540 Broadway, 5th Floor, Albany, New York 12207 Phone: (518) 465-1473 Fax: (518) 465-0506 www.nysac.org President: Hon. MaryEllen Odell, Putnam County Executive Director: Stephen J. Acquario, Esq. March 22, 2018 The Honorable John Flanagan The Honorable Carl Heastie New York State Senate New York State Assembly Capitol Capitol Albany, NY 122224 Albany, NY 12224 County officials recognize the difficult task you face in finalizing budget negotiations for the coming fiscal year. In addition to local service delivery, county government has long operated as the State’s administrative arm, delivering and financing a wide variety of state programs and initiatives. In recent years, the Governor and Legislature have worked to reduce out year mandated costs on counties and those efforts have helped counties stay under the tax cap. As you continue your deliberations to finalize issues in the State Budget we encourage you to consider the following budget items of importance to counties that will likely fall under the purview of the General Budget Conference Committee. Internet Fairness Conformity Act There are three key points of clarification concerning this issue: • This is about providing a tax advantage to out of state business at the expense of New York businesses – NY must level the playing field • This is not a new tax, in fact, the tax is still being paid by consumers – not at the point of sale but when they pay their property tax bill • This is a state’s rights issue – we do not need to wait for the Supreme Court or Congress to intervene How consumers shop has changed dramatically over the last decade, but the state’s outdated tax code has not kept pace. -

New York Election Update: 2018

Alert | New York Government Law & Policy November 2018 New York Election Update: 2018 With all statewide constitutional offices and every state legislative seat – both in the Senate and Assembly – plus one U.S. Senate seat and all members of Congress up for election, there were many races to follow in New York this year. The most attention was devoted to the State Senate, where, going into Election Day, Republicans maintained control by just one vote, and only due to the decision of Brooklyn Democratic Senator Simcha Felder to continue to conference with Republicans. Ultimately, the surprise in New York was not that Democrats won a majority of Senate seats, but rather the large number of seats that they secured. Statewide On the eve of Election Day, the media was reporting that Republican Dutchess County Executive Marc Molinaro had tightened the gap between him and two-term incumbent Democrat Governor Cuomo, to 13 points. Once voters got to the polls, however, the outcome was better for Cuomo, who appears to have won by more than 22 percent. The other statewide Democratic candidates experienced a similar level of success. Incumbent Comptroller Tom DiNapoli handily won reelection over first-time challenger Jonathan Trichter by approximately 34 points. Additionally, the victory of New York City Public Advocate Letitia “Tish” James for attorney general marks a historic change, as she will be the first woman of color to head that office – or any statewide office in New York. James received approximately 60 percent of the vote, with Republican Keith Wofford receiving about 34 percent. © 2018 Greenberg Traurig, LLP State Senate (Possibly 40 D, 23 R) Primary night proved difficult for incumbent senators, particularly those who had been affiliated with the now-defunct Independent Democratic Conference (IDC). -

Sample Tweets Below to Share Recommendations with Your New York State And/Or New York City Elected Officials, Tagging #Empoweredeaters

--- ADVOCACY ON TWITTER --- For the week of January 22 The Empowered Eaters reports include policy recommendations for ensuring all New Yorkers can be empowered eaters, with access to great nutrition education. Please use the sample Tweets below to share recommendations with your New York State and/or New York City elected officials, tagging #EmpoweredEaters. See below for more details. Please feel free to use any of THESE PHOTOS in your posts. ADVOCACY IN NYS Governor’s Office: @NYGovCuomo New York State Assembly: (Don’t know your district? Click HERE) New York State Senate: (Don’t know your district? Click HERE) D1 –Sen. Kenneth LaValle (@senatorlavalle) D29 – Jose Serrano (@SenatorSerrano) D3 – Sen. Thomas Croci (@tomcroci) D30 – Brian Benjamin (@NYSenBenjamin) D4 – Sen. Phil Boyle (@PhilBoyleNY) D33 – J. Gustavo Rivera (@NYSenatorRivera) D5 – Sen. Carl Marcellino (@Senator98) D34 – Jeffrey Klein (@JeffKleinNY) D6 – Kemp Hannon (@kemphannon) D35 – Andrea Stewart-Cousins (@AndreaSCousins) D7 – Elaine Phillips (@SenatorPhillips) D36 – Jamaal Bailey (@jamaaltbailey) D8 – John Brooks (@Brooks4LINY) D38 – David Carlucci (@DavidCarlucci) D9 – Todd Kaminsky (@toddkaminsky) D39 – William Larkin (@SenatorLarkin) D10 – James Sanders (@JamesSandersJR) D40 – Terrence P. Murphy (@vote4murphy) D11 – Tony Avella (@TonyAvella) D41 – Susan Serino (@Sueserino4ny) D12 – Michael Gianaris (@SenGianaris) D42 – John Bonacic (@JohnBonacic) D13 – Jose Peralta (@SenatorPeralta D43 – Kathleen Marchione (@kathymarchione) D14 – Leroy Comrie (@LeroyComrie) D44 -

C:\Documents and Settings\Nancy.Stuligross\Local

OF DELAWARE COUNTY, NEW YORK 1 ORGANIZATIONAL MEETING DELAWARE COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS January 5, 2005 The organizational meeting of the Delaware County Board of Supervisors was held Wednesday, January 5, 2005 at 1:00 P.M. in the Supervisors’ Room of the Senator Charles D. Cook County Office Building, 111 Main Street, Delhi, New York. The Clerk of the Board, Christa M. Schafer, called the meeting to order and read the Notice of Meeting: TO ALL SUPERVISORS: Pursuant to County Law, §151 and Board Rule 1, the Organizational Meeting of the Delaware County Board of Supervisors will be held in the Supervisors' Room of the Senator Charles D. Cook County Office Building, 111 Main Street, Delhi, New York on Wednesday, January 5, 2005 at 1:00 P.M. The meeting is called for the purpose of organizing for the year 2005, including election of a Chairman, Vice Chairman, and Clerk. Any other business that may properly be brought before the Board will be conducted. Christa M. Schafer, Clerk Delaware County Board of Supervisors The Clerk called the roll by towns and the following Supervisors were present: Martin A. Donnelly 134 Damgaard Road Andes Tina B. Molé P.O. Box 63, Bovina Center Bovina Lucille R. Freyer 831 Horton Brook, Roscoe Colchester Todd Rider P.O. Box 152, Davenport Center Davenport Peter J. Bracci 931 Dick Mason Road Delhi Stanley E. Woodford 668 Old Route 10 Deposit Donald Smith 21 Bartlett Hollow Road Franklin Wayne E. Marshfield 6754 Basin Clove Road Hamden James E. Eisel, Sr. 25171 State Highway 23 Harpersfield George Haynes Main Street, P.O. -

NYS Legislation Update Bill Numbers Are Reset in Jan of Odd Numbered Years

NYS Legislation Update Bill numbers are reset in Jan of odd numbered years. New York State bills to watch. Full text of Assembly bills can be found at http://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/ or http://www.nysenate.gov/legislation for NYS Senate bills. Remember in Nov 2014 see how your NYS Senator & Assembly member voted on 2013 Gun control bill SAFE Act and the 2011 A08354 Redefining (Gay) marriage law. Go to bottom of this section to view the roll call votes. Note If you do NOT want your Gun ownership, name and address to appear on the internet you must send a letter to “OPT Out” There are also new rules for keeping Gun permits Go to “Pro 2nd Amendment & Gun Control Section” section below for details You can e-mail your Assemblyman at http://assembly.state.ny.us/mem/ . You can e-mail NYS Senator at http://www.nysenate.gov/ A07994 S06267-2013 (Repeal Common Core) Relates(repeal) to the common core state standards initiative and the race to the top program. Sponsor Graf, BALL Co-sponsors McDonough, Montesano, Giglio, Blankenbush, Borelli, Lupinacci, Ceretto, Friend, Curran, Tenney, Corwin, McKevitt, Hawley, Garbarino, Lalor, Crouch, Goodell, Duprey, McLaughlin, Katz, Raia, Stec, Tedisco, Palmesano, Butler, Kolb, Ra, Lopez P, DiPietro, Johns, Nojay, Malliotakis, MAZIARZ If your NYS state Senator or Assemblyperson is NOT on the list of Sponsors or Co-Sponsors Please ask them to become a co-sponsor. New major unfunded mandate proposed! Cuomo commission pushes longer school day, year & PRE-K Every school would need a major increase in property taxes. -

October 6, 2015 Hon. John Bonacic Chair, Judiciary Committee New

DEBRA L. RASKIN PRESIDENT PHONE: (212) 382-6700 FAX: (212) 768-8116 [email protected] October 6, 2015 Hon. John Bonacic Chair, Judiciary Committee New York State Senate Legislative Office Building 509 Albany, NY 12247 Re: Mass Incarceration: Seizing the Moment for Reform Dear Sen. Bonacic: The New York City Bar Association, through the combined efforts of its Executive Committee and various committees with relevant expertise, has issued the enclosed report Mass Incarceration: Seizing the Moment for Reform. In it, we urge federal and state leaders to address the significant negative consequences of mass incarceration and offer the following six policy recommendations: (1) repeal or reduce mandatory minimum sentencing provisions; (2) reduce the sentences recommended by sentencing guidelines and similar laws for non-violent offenses; (3) expand the sentencing alternatives to prison including drug programs, mental health programs and job training programs; and, in cases of incarceration, expand the availability of rehabilitative services, including counseling and educational opportunities, during and following incarceration so that individuals can successfully reenter society and avoid recidivism; (4) eliminate or reduce financial conditions of pretrial release; (5) provide opportunities for individuals with misdemeanor and non-violent felony convictions to seal those records to prevent employment and other discrimination; and (6) enact legislation to raise the age of juvenile jurisdiction from 16 to 18 years old. We ask that you join in the growing bipartisan support for criminal justice reform and include the issues of mass incarceration in your agenda this year so we can begin to address its extraordinarily damaging effects and seize the opportunity for change that exists right now.