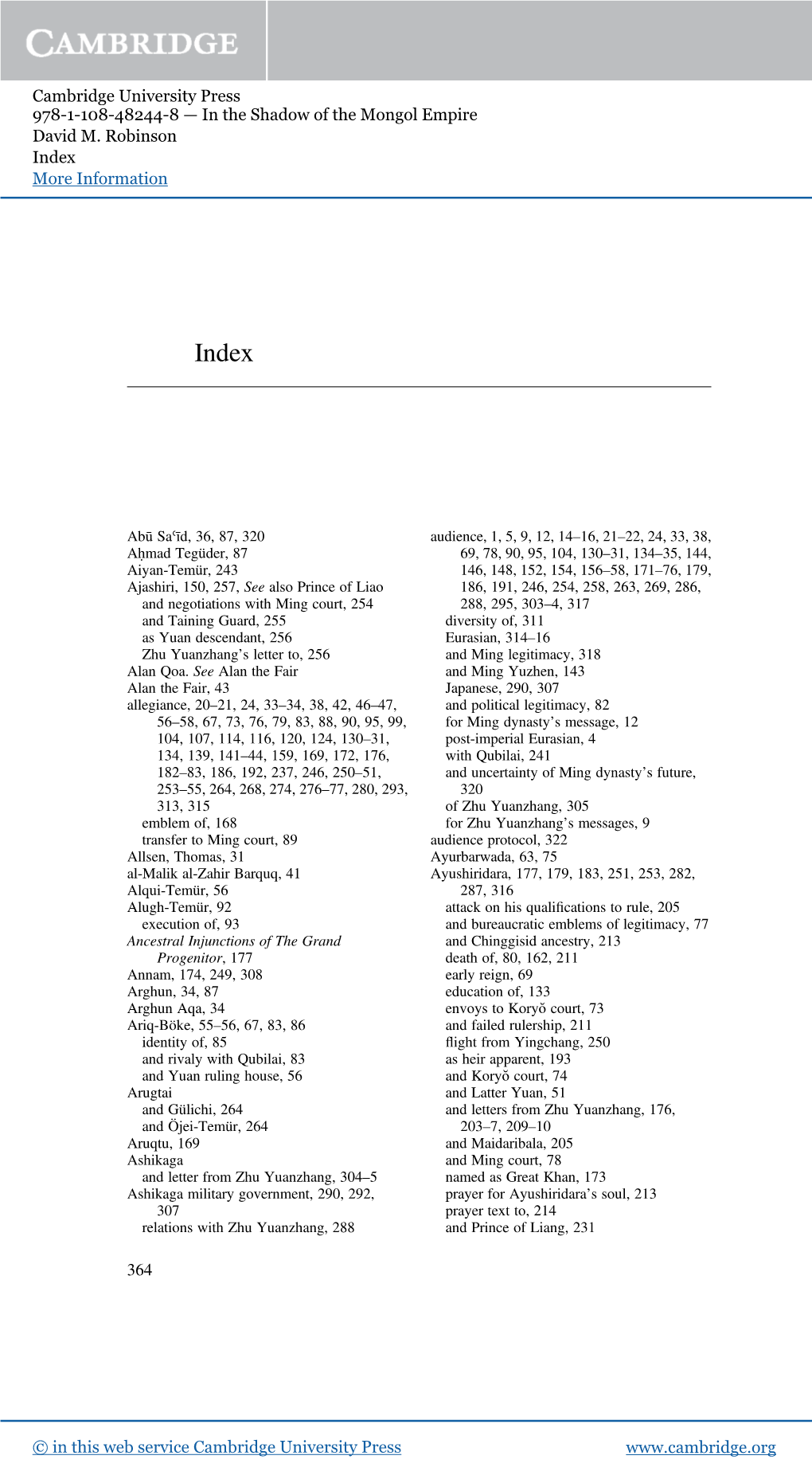

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48244-8 — in the Shadow of the Mongol Empire David M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: the Emergence of the Yunnanese

Between Winds and Clouds Bin Yang Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: The Emergence of the Yunnanese Introduction As the state began sending soldiers and their families, predominantly Han Chinese, to Yunnan, 1 the Ming military presence there became part of a project of colonization. Soldiers were joined by land-hungry farmers, exiled officials, and profit-driven merchants so that, by the end of the Ming period, the Han Chinese had become the largest ethnic population in Yunnan. Dramatically changing local demography, and consequently economic and cultural patterns, this massive and diverse influx laid the foundations for the social makeup of contemporary Yunnan. The interaction of the large numbers of Han immigrants with the indigenous peoples created a 2 new hybrid society, some members of which began to identify themselves as Yunnanese (yunnanren) for the first time. Previously, there had been no such concept of unity, since the indigenous peoples differentiated themselves by ethnicity or clan and tribal affiliations. This chapter will explore the process that led to this new identity and its reciprocal impact on the concept of Chineseness. Using primary sources, I will first introduce the indigenous peoples and their social customs 3 during the Yuan and early Ming period before the massive influx of Chinese immigrants. Second, I will review the migration waves during the Ming Dynasty and examine interactions between Han Chinese and the indigenous population. The giant and far-reaching impact of Han migrations on local society, or the process of sinicization, that has drawn a lot of scholarly attention, will be further examined here; the influence of the indigenous culture on Chinese migrants—a process that has won little attention—will also be scrutinized. -

SDN Changes 2014

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO THE Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List SINCE JANUARY 1, 2014 This publication of Treasury's Office of Foreign AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah (a.k.a. SAHAB, Qari; IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN Assets Control ("OFAC") is designed as a a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH; a.k.a. reference tool providing actual notice of actions by 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. OFAC with respect to Specially Designated Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, "SUPPORTERS OF ISLAMIC LAW"), Tunisia Nationals and other entities whose property is Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) [FTO] [SDGT]. blocked, to assist the public in complying with the [SDGT]. AL-RAYA ESTABLISHMENT FOR MEDIA various sanctions programs administered by SAHAB, Qari (a.k.a. AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah; PRODUCTION (a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA; OFAC. The latest changes may appear here prior a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'A BRIGADE; a.k.a. to their publication in the Federal Register, and it 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'A IN BENGHAZI; a.k.a. is intended that users rely on changes indicated in Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN LIBYA; a.k.a. ANSAR this document that post-date the most recent Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) AL-SHARIAH; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIAH Federal Register publication with respect to a [SDGT]. -

Sunnahmuakada.Wordpress.Com Sayyid Rami Al Rifai Issue #4

Issue #4 The Islamic Journal SunnahMuakada.wordpress.com Sayyid Rami al Rifai Table Of Contents Foward 1) Man Is Always In A State Of Loss In The Universe 2) Ablution (Wudu) Is Worth Half Of Our Iman (Faith) and It's Af- fects On The Unseen (Subatomic) World 3) The Role Of Wudu (Ablution) In Being Happy 4)The Spiritual Imapct Of Perfecting The Self And The Impor- tance of Spiritual Training 5) Allah Himself Is The One Who Categorised The Nafs (Self) 6)The Accupunture Of Asia The Lataif Of Islam and Their Origin Related Material 1) 1001 Years Of Missing Islamic Martial Arts 2) Tariqah's Existed Among The First Generations Of Muslims (Sa- laf) 3) Imam Ibn Kathir and Sufism 4)The Debate Between Ibn Ata Allah and Ibn Taymiyah On Tasaw- wuf i Foward Bismillahi rahmani raheem Assalamu Alaikum, The Islamic Journal is a unique Journal in that it doesn’t follow the usual methods of other academic journals. It came about as a re- sult of a book I was writing called “The Knowledge Behind The Terminology and Concepts in Tassawwuf and It’s Origin”, the title is as descriptive as possible because the book was written in the same style as classical islamic texts, a single document without any chapter’s since they were a later invention which hindered the flow of the book. That book looked into the Islamic science of Ihsan, Human perfec- tion, were it’s terminology and concepts came from, what they mean and the knowledge and science they were based on. -

Protagonist of Qubilai Khan's Unsuccessful

BUQA CHĪNGSĀNG: PROTAGONIST OF QUBILAI KHAN’S UNSUCCESSFUL COUP ATTEMPT AGAINST THE HÜLEGÜID DYNASTY MUSTAFA UYAR* It is generally accepted that the dissolution of the Mongol Empire began in 1259, following the death of Möngke the Great Khan (1251–59)1. Fierce conflicts were to arise between the khan candidates for the empty throne of the Great Khanate. Qubilai (1260–94), the brother of Möngke in China, was declared Great Khan on 5 May 1260 in the emergency qurultai assembled in K’ai-p’ing, which is quite far from Qara-Qorum, the principal capital of Mongolia2. This event started the conflicts within the Mongolian Khanate. The first person to object to the election of the Great Khan was his younger brother Ariq Böke (1259–64), another son of Qubilai’s mother Sorqoqtani Beki. Being Möngke’s brother, just as Qubilai was, he saw himself as the real owner of the Great Khanate, since he was the ruler of Qara-Qorum, the main capital of the Mongol Khanate. Shortly after Qubilai was declared Khan, Ariq Böke was also declared Great Khan in June of the same year3. Now something unprecedented happened: there were two competing Great Khans present in the Mongol Empire, and both received support from different parts of the family of the empire. The four Mongol khanates, which should theo- retically have owed obedience to the Great Khan, began to act completely in their own interests: the Khan of the Golden Horde, Barka (1257–66) supported Böke. * Assoc. Prof., Ankara University, Faculty of Languages, History and Geography, Department of History, Ankara/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 For further information on the dissolution of the Mongol Empire, see D. -

ASJ Introduction to "Historical and Cultural Significance of Admiral Zheng He's Ocean Voyages"

ASJ Introduction to "Historical and Cultural Significance of Admiral Zheng He's Ocean Voyages" Those in power control the future by controlling the past, wrote George Orwell. Nowhere is this truth more dead on target than in European historiography, with its hubris-that enduring sense of being better than the rest. This claim of European superiority, according to Alam (2002), has been put forward with regard to rationality, freedom, individuality, inventiveness, daring, curiosity and tolerance; in turn, these qualities have been translated into superior achievements in technology, wars, management, capitalism, industrialization, and shipping, among others. A case in point is the European effort to explain, or explain away, Zheng He's expeditions in the l4'h century as a case of irrational decision making, of an inability to resist the gratification of whims and desires of the voyager's Chinese masters. By contrast, European expeditions were presented as technological triumphs in an era of rationalism and economic adventure. Such Eurocentrism takes a variety of forms. In the 1990 BBC television documentary series Road to Xanadu, for instance, Zheng He's maritime exploration, according to Cao (2006), is assailed as "an expendable luxury"-an impractical exercise in the consumption (rather than production) of material wealth. To emphasize the difference, the documentary suggests that when Europe embarked on its profit-seeking overseas colonial undertaking, the aim was "to grasp the riches of trade 25 26 with Asia." Or again, it is common for European historiographers to devalue China's maritime reach Gong after Zheng He's expeditions), by asking rhetorically (as did Landes, 1998) why European sailing vessels could call at Shanghai or Canton, while no Chinese junks ever anchored in London (Goldstone, 2001 ). -

Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi POWER, POLITICS, AND TRADITION IN THE MONGOL EMPIRE AND THE ĪlkhānaTE OF IRAN OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Īlkhānate of Iran MICHAEL HOPE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 08/08/16, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6D P, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Michael Hope 2016 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2016932271 ISBN 978–0–19–876859–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

The Coins of the Later Ilkhanids

THE COINS OF THE LATER ILKHANIDS : A TYPOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 BY SHEILA S. BLAIR Ghazan Khan was undoubtedly the most brilliant of the Ilkhanid rulers of Persia: not only a commander and statesman, he was also a linguist, architect and bibliophile. One of his most lasting contribu- tions was the reorganization of Iran's financial system. Upon his accession to the throne, the economy was in total chaos: his prede- cessor Gaykhatf's stop-gap issue of paper money to fill an empty treasury had been a fiasco 2), and the civil wars among Gaykhatu, Baydu, and Ghazan had done nothing to restore trade or confidence in the economy. Under the direction of his vizier Rashid al-Din, Ghazan delivered an edict ordering the standardization of the coinage in weight, purity, and type 3). Ghazan's standard double-dirham became the basis of Iran's monetary system for the next century. At varying intervals, however, the standard type was changed: a new shape cartouche was introduced, with slight variations in legend. These new types were sometimes issued at a modified weight standard. This paper will analyze the successive standard issues of Ghazan and his two successors, Uljaytu and Abu Said, in order to show when and why these new types were introduced. Following a des- cription of the successive types 4), the changes will be explained through 296 an investigation of the metrology and a correlation of these changes in type with economic and political history. Another article will pursue the problem of mint organization and regionalization within this standard imperial system 5). -

Il-Khanate Empire

1 Il-Khanate Empire 1250s, after the new Great Khan, Möngke (r.1251–1259), sent his brother Hülegü to MICHAL BIRAN expand Mongol territories into western Asia, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel primarily against the Assassins, an extreme Isma‘ilite-Shi‘ite sect specializing in political The Il-Khanate was a Mongol state that ruled murder, and the Abbasid Caliphate. Hülegü in Western Asia c.1256–1335. It was known left Mongolia in 1253. In 1256, he defeated to the Mongols as ulus Hülegü, the people the Assassins at Alamut, next to the Caspian or state of Hülegü (1218–1265), the dynasty’s Sea, adding to his retinue Nasir al-Din al- founder and grandson of Chinggis Khan Tusi, one of the greatest polymaths of the (Genghis Khan). Centered in Iran and Muslim world, who became his astrologer Azerbaijan but ruling also over Iraq, Turkme- and trusted advisor. In 1258, with the help nistan, and parts of Afghanistan, Anatolia, of various Mongol tributaries, including and the southern Caucasus (Georgia, many Muslims, he brutally conquered Bagh- Armenia), the Il-Khanate was a highly cos- dad, eliminating the Abbasid Caliphate that mopolitan empire that had close connections had nominally led the Muslim world for more with China and Western Europe. It also had a than 500 years (750–1258). Hülegü continued composite administration and legacy that into Syria, but withdrew most of his troops combined Mongol, Iranian, and Muslim after hearing of Möngke’s death (1259). The elements, and produced some outstanding defeat of the remnants of his troops by the cultural achievements. -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, -

The Mongol City of Ghazaniyya: Destruction, Spatial Reconstruction, and Preservation of the Urban Heritage1

Atri Hatef Naiemi The Mongol City of Ghazaniyya: Destruction, Spatial Reconstruction, and Preservation of the Urban Heritage1 Hülegü Khan (r. 1256-1265), a grandson of Chinggis Khan, founded the Ilkhanate in Iran in 1256 as the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. Mongol campaigns in Iran in the thirteenth century caused extensive destruction in different aspects of the Iranians’ social life and built environment. However, the political stability after the arrival of Hülegü intensified the process of urban development. Along with the reconstruction of the cities that had been extensively destroyed during the Mongol attack, the Ilkhans founded a number of new settlements. Their architectural and urban projects were mostly conducted in the northwest of present-day Iran, with some exceptions, for instance the city of Khabushan in Khurasan which was largely rebuilt by Hülegü and the notables of his court.2 In western Iran, Hülegü firstly focused his attention on the reconstruction of Baghdad, but following the designation of Azerbaijan as the headquarters of the Mongols, his urban development activities extended to this region. Maragha was chosen as the first capital of the Mongols and the most 1 This article has been adapted from a lecture presented in November 2019 at the Aga Khan Program in MIT. The research for this project has been facilitated by fellowship held with the Aga Khan program of MIT. I would like to thank Professors Nasser Rabbat and James Wescoat for their hospitality during the four months I spent at MIT in 2019. 2 In addition to Hülegü, Ghazan Khan also erected magnificent buildings in Khabushan. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

The Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming

The Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming 大明皇陵之碑 With translation into English, annotations and commentary by Laurie Dennis October 2017 The town of Fengyang 凤阳, to the north of Anhui Province in the heart of China, may seem at first glance to be an ordinary, and rather unremarkable, provincial outpost. But carefully preserved in a park southwest of the town lies a key site for the Ming Dynasty, which ruled the Middle Kingdom from 1368 until 1644. Fengyang is where the eventual dynastic founder lost most of his family to the plague demons. This founder, Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋, was a grieving and impoverished peasant youth when he buried his parents and brother and nephew on a remote hillside near the town that he later expanded, renamed, and tried (unsuccessfully) to make his dynastic capital. Though Zhu had to leave his home to survive in the aftermath of the burial, he was a filial son, and regretted not being able to tend his family graves. Soon after becoming emperor, he transformed his family’s unmarked plots into a grand imperial cemetery for the House of Zhu, flanked by imposing statues (see the photo above, taken in 2006). He ordered that a stone tablet be placed before the graves, and carved with the words he wanted his descendants to read and ponder for generation after generation. The focus of this monograph is my translation of this remarkable text. The stele inscribed with the words of Zhu Yuanzhang, known as the Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming 大明皇陵之碑, or the Huangling Bei, stands over 7 meters high and is borne on the back of a stone turtle.