JBTM 15.2 Fall 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A PDF Companion to the Audiobook APPENDIX 1: EXPERT CONTRIBUTIONS

A PDF Companion to the Audiobook APPENDIX 1: EXPERT CONTRIBUTIONS Growing Up Muslim in America ABDU MURRAY Contributing to Part 1: “Called to Prayer” Abdu Murray is a lawyer, apologist, and former Shia Muslim. Author of two published books on Islam and other major worldviews, he is currently president of Embrace the Truth International. IN THE SALTY-WHITE LANDSCAPE of the Detroit suburb of my youth, my family was a dash of pepper. We stood out because, at that time, we were exotic — one of the few Muslim families in the area. And I took Islam seriously so that I could stand out even more because that would cause my friends to ask questions about my faith. That, in turn, would lead to op- portunities to share what I considered to be the beauty and truth of Islam with the low-hang- ing fruit of the many non-Muslim, mostly Christian, individuals around me. I was like many Muslims I knew. Even as a youth, I loved talking about God and my Islamic faith. I was puzzled that the non-Muslims around me found it so uncomfortable to talk about matters of religion. Don’t these Christians really believe their traditions? If their message is true, why are they so afraid to talk about it? The answer, I told myself, is that Christians know deep down that their religion is silly. They only need to be shown the truth of Islam to see the true path. Muslims get that kind of confidence from religious training received during their child- hood and teen years. -

Harmonising God's Sovereignty and Man's Free Will

Introduction Historical Overview Arminianism & Calvinism Molinism Criticisms Conclusion An Introduction to Molinism Harmonising God’s Sovereignty and Man’s Free Will Wessel Venter http://www.siyach.org/ 2016-06-07 Introduction Historical Overview Arminianism & Calvinism Molinism Criticisms Conclusion Introduction Introduction Historical Overview Arminianism & Calvinism Molinism Criticisms Conclusion Mysteries of the Christian Faith 1. How can God be One, but Three Persons? 2. How can Jesus simultaneously be fully man and fully God? 3. How can God be sovereign over our lives, yet people still have free will? Introduction Historical Overview Arminianism & Calvinism Molinism Criticisms Conclusion Mysteries of the Christian Faith 1. How can God be One, but Three Persons? 2. How can Jesus simultaneously be fully man and fully God? 3. How can God be sovereign over our lives, yet people still have free will? Introduction Historical Overview Arminianism & Calvinism Molinism Criticisms Conclusion Table of Contents 4 Molinism 1 Introduction Definition of Molinism Preliminary Definitions Counterfactuals 2 Historical Overview Middle Knowledge Pelagian Controversy 5 Objections and Criticisms Thomas Aquinas Miscellaneous The Reformation Thinly Veiled Open Theism The Counter-Reformation The Truth/Existence of Further History CCFs Secular Debate Divine Voodoo Worlds 3 Arminianism and Calvinism Grounding Problem Arminianism Not Biblical Calvinism 6 Applications and Conclusion Arminianism vs Calvinism Applications Introduction Historical Overview Arminianism & Calvinism Molinism Criticisms Conclusion Definitions Preliminary DefinitionsI Definition (Soteriology[9]) “The study of salvation.” In Christianity this includes topics such as regeneration, election, predestination, repentance, sanctification, justification, glorification, etc. Definition (Possible World) A world that could have been, if history had progressed differently. E.g., if there was not a traffic jam, I would not have been late for work on Monday. -

Reconciling Universal Salvation and Freedom of Choice in Origen of Alexandria

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Reconciling Universal Salvation and Freedom of Choice in Origen of Alexandria Lee W. Sytsma Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sytsma, Lee W., "Reconciling Universal Salvation and Freedom of Choice in Origen of Alexandria" (2018). Dissertations (1934 -). 769. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/769 RECONCILING UNIVERSAL SALVATION AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN ORIGEN OF ALEXANDRIA by Lee W. Sytsma, B.A., M.T.S. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2018 ABSTRACT RECONCILING UNIVERSAL SALVATION AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN ORIGEN OF ALEXANDRIA Lee W. Sytsma, B.A., M.T.S. Marquette University, 2018 Origen has traditionally been famous for his universalism, but many scholars now express doubt that Origen believed in a universal and permanent apocatastasis. This is because many scholars are convinced that Origen’s teaching on moral autonomy (or freedom of choice) is logically incompatible with the notion that God foreordains every soul’s future destiny. Those few scholars who do argue that Origen believed in both moral autonomy and universal salvation either do not know how to reconcile these two views in Origen’s theology, or their proposed “solutions” are not convincing. In this dissertation I make two preliminary arguments which allow the question of logical compatibility to come into focus. -

Curriculum Vitae Ken Chitwood -June 2020

Curriculum Vitae Ken Chitwood www.kenchitwood.com -June 2020- Education: • University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 2014 - 2019. Ph.D. Religion in the Americas. o Dissertation, “Los Musulmanes Boricuas: Puerto Rican Muslims and the Idea of Cosmopolitanism.” o Graduate Certificate, Global Islamic Studies. • Concordia University, Irvine, CA, 2014. M.A. Theology and Culture (May, 2014). o Thesis, “Islam en Español: The Conversion Pathways of Latina/o Muslims in the U.S.” • Concordia University, Irvine, CA, 2007. B.A. Christian Education Leadership & Theological Studies (May, 2007). Professional Employment: • Fritz Thyssen Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies, Freie Universität Berlin. Berlin, Germany. March 2020 – March 2022. o Conducted research in conjunction with the Graduate School, mentored and worked with graduate students, and participated in the academic life of the Graduate School. • Lecturer, Islamwissenschaft, Otto Friedrich Universität Bamberg. Bamberg, Germany. March 2020 – July 2020. o Delivered lectures and taught a course on Islam and Muslim communities in the Americas. • Journalism Consultant, King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID). Vienna, Austria. February 2020 – December 2020. o Writing and photography/videography for special five year fellowship progress report. • Staff Writer, Religions for Peace, 10th World Assembly of Religions for Peace. Lindau, Germany. July – August 2019. o Working with the established Drafting Committee and the Secretary General of Religions for Peace, I oversaw the writing of the Assembly Declaration, which will guide the focus of the network for the next five years under the theme “Caring for our Common Future.” • Journalist-Fellow, University of Southern California Center for Religion and Civic Culture, Spiritual Exemplars Project. -

Doctrinal Controversies of the Carolingian Renaissance: Gottschalk of Orbais’ Teachings on Predestination*

ROCZNIKI FILOZOFICZNE Tom LXV, numer 3 – 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18290/rf.2017.65.3-3 ANDRZEJ P. STEFAŃCZYK * DOCTRINAL CONTROVERSIES OF THE CAROLINGIAN RENAISSANCE: GOTTSCHALK OF ORBAIS’ TEACHINGS ON PREDESTINATION* This paper is intended to outline the main areas of controversy in the dispute over predestination in the 9th century, which shook up or electrified the whole world of contemporary Western Christianity and was the most se- rious doctrinal crisis since Christian antiquity. In the first part I will sketch out the consequences of the writings of St. Augustine and the revival of sci- entific life and theological and philosophical reflection, which resulted in the emergence of new solutions and aporias in Christian doctrine—the dispute over the Eucharist and the controversy about trina deitas. In the second part, which constitutes the main body of the article, I will focus on the presenta- tion of four sources of controversies in the dispute over predestination, whose inventor and proponent was Gottschalk of Orbais, namely: (i) the concept of God, (ii) the meaning of grace, nature and free will, (iii) the rela- tion of foreknowledge to predestination, and (iv) the doctrine of redemption, i.e., in particular, the relation of justice to mercy. The article is mainly an attempt at an interpretation of the texts of the epoch, mainly by Gottschalk of Orbais1 and his adversary, Hincmar of Reims.2 I will point out the dif- Dr ANDRZEJ P. STEFAŃCZYK — Katedra Historii Filozofii Starożytnej i Średniowiecznej, Wy- dział Filozofii Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego Jana Pawła II; adres do korespondencji: Al. -

Inventory to the Baptist World Congress Collection

BAPTIST CONGRESS PROCEEDINGS COLLECTION AR 40 2 Baptist Congress Proceedings Collection AR 40 Prepared by: Taffey Hall, Archivist Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives August 2004 Updated October, 2011 Summary Main Entry: Baptist Congress Proceedings Collection Date Span: 1885 – 1912 Abstract: Collection contains papers, addresses, and discussions from Baptist Congress meetings. Title page of proceedings includes list of speakers and topics. Baptist intellectual think tank from 1882 – 1912 and forum for theological, social, and ethical discussions and debates among members of Baptist churches. Modeled after the Episcopal Church Congress and existed to “promote a healthful sentiment among Baptists through free and courteous discussion of current questions by suitable persons.” Size: 1.5 linear ft. Collection#: AR 40 Biographical Sketch The Baptist Congress, a pioneering Baptist intellectual think tank and forum for theological, social, and ethical discussions and debates among members of Baptist churches, existed from 1882 to 1912. The need for an intellectual outlet through which Baptists from various traditions could discuss important and relevant issues of the time was first proposed by Providence, Rhode Island pastor Elias Henry Johnson. Johnson and thirteen other prominent Baptist scholars met in New York City November 29, 1881 and held an informal discussion panel on germane topics. At the meeting, Johnson officially proposed the formation of a Baptist Congress. The first official meeting of the organization was held in Brooklyn, New York in 1882. The Baptist Congress met annually for the next thirty years across the United States and Canada, with the exception of 1891 when no meeting was held. Due to decreasing attendance, the Baptist Congress held its last meeting in Ithaca, New York in 1912. -

Norman Geisler on Molinism

Norman Geisler on Molinism http://normangeisler.com What did Norm Geisler say about the Middle-Knowledge, Molinism, and the thought of Luis de Molina? Several people have asked about this by email. This blogpost attempts to provide an answer based on six sources of Norm’s comments on Molinism: 1) Geisler, Norman L. “Molinism,” in Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1999) pp. 493–495. 2) Geisler, Norman L. Chosen but Free: A Balanced View of Divine Election, 2nd edition (Bethany House, 1999) pp. 51-55 3) Geisler, Norman L. Systematic Theology, Volume II: God, Creation (Bethany House, 2003) pp. 206-207 4) Geisler, Norman L. Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences (Baker Books, 1995), p. 450-446 5) Classroom lectures by Norm Geisler on God’s Immutability in the course TH540 (“God and Creation”) at Veritas International University, circa 2013. Class #3 - https://vimeo.com/72793620 6) Four private emails answered by Norm Although some paragraphs have been reworded slightly in the attempt to avoid copyright infringement, and the sources have been blended together in a somewhat repetitive and less-than-seamless way, this compilation remains faithful to what Norm wrote and said. The reader is encouraged to acquire the four books cited above to read this material in its original contexts. Apologies are offered in advance for the somewhat hurried and patchwork-nature of this compilation. LUIS DE MOLINA (A.D. 1535–1600) was born in Cuenca, New Castile, Spain. He joined the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) and became a theologian. The theology that bears his name claims to protect the integrity of human free will better than any other system. -

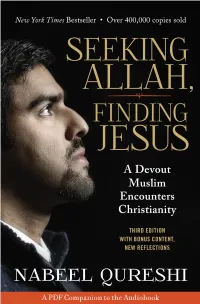

F:\NABEEL QURESHI.Wpd

NABEEL QURESHI The following bio is taken from Dr. Qureshi’s official site: “Dr. Nabeel Qureshi is a former devout Muslim who was convinced of the truth of the Gospel through historical reasoning and a spiritual search for God. Since his conversion, he has dedicated his life to spreading the Gospel through teaching, preaching, writing, and debating. Nabeel has given lectures at universities and seminaries throughout North America, including New York University, Rutgers, the University of North Carolina, the University of Ottawa, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and Biola University. He has participated in 17 moderated, public debates around North America, Europe, and Asia. His focus is on the foundations of the Christian faith and the early history and teachings of Islam. Nabeel is a member of the speaking team at Ravi Zacharias International Ministries. He holds an MD from Eastern Virginia Medical School, an MA in Christian apologetics from Biola University, and an MA from Duke University in Religion.” (In case you didn’t know Dr. Qureshi died of stomach cancer on Sept.16, 2017 at the age of 34.) Wikipedia observes that his first book, Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus, was awarded the Christian Book Award for both “Best New Author” and “Best Non-Fiction” of 2015. Dr. Quershi was the first to earn both honors. They also state that Qureshi lectured to students at more than 100 universities, including Oxford, Columbia, Dartmouth, Cornell, Johns Hopkins, and the University of Hong Kong. He has participated in 18 moderated, public debates around North America, Europe, and Asia. -

Kane42077 Ch13.Qxd 1/19/05 16:30 Page 147

kane42077_ch13.qxd 1/19/05 16:30 Page 147 CHAPTER 13 c Predestination, Divine Foreknowledge, and Free Will 1. Religious Belief and Free Will Debates about free will are impacted by religion as well as by science, as noted in chapter 1. Indeed, for many people, religion is the context in which questions about free will first arise. The following personal state- ment by philosopher William Rowe nicely expresses the experiences of many religious believers who first confront the problem of free will: As a seventeen year old convert to a quite orthodox branch of Protestantism, the first theological problem to concern me was the question of Divine Predestination and Human Freedom. Somewhere I read the following line from the Westminster Confession: “God from all eternity did...freely and unchangeably ordain whatsoever comes to pass.” In many ways I was attracted to this idea. It seemed to express the majesty and power of God over all that he had created. It also led me to take an optimistic view of events in my own life and the lives of others, events which struck me as bad or unfor- tunate. For I now viewed them as planned by God before the creation of the world—thus they must serve some good purpose unknown to me. My own conversion, I reasoned, must also have been ordained to happen, just as the failure of others to be converted must have been similarly ordained. But at this point in my reflections, I hit upon a difficulty, a difficulty that made me think harder than I ever had before in my life. -

Fishtrap United Baptist Church Fishtrap Vicinity Johnson County

Fishtrap United Baptist Church HABS No. KY-135 Fishtrap ■ Vicinity Johnson County m Kentucky iT.A/ PHOTOGRAPHS m WRITTEN HISTORICAL MD DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 202^3 H/^.KY.5$-FlstfT.Vf HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY HABS No. KY-135 FISHTRAP UNITED BAPTIST CHURCH Location: Near Paint Creek, between Blanton and Colvin Branches, Fishtrap vicinity, Johnson County, Kentucky. USGS Oil Spring Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mer- cator Coordinates: 1?.332891.^19506. Present Owner: United States Army Corps of Engineers, Huntington District, P. 0. Box 2127, Huntington, West Virginia 25721 (1976). Present Occupant: Fishtrap United Baptist Church. Present Use: Religious Services. The church is to he relocated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, Huntington District, in order to protect it from flooding due to the construction of a dam and resevoir by impounding Paint Creek. The church will be moved to Federal prop- erty on the Colvin Branch. Significance: Fishtrap United Baptist Church, built I8U3, "was among the earliest log churches in Johnson County (Hall, Johnson County, page 292). Covered with weatherboard in the late 19th century, the church is notable for its simplicity and fine interior woodwork. PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. History of Structure: The Union Association of United Baptists in Kentucky was orga- nized in October 1837 by Elders William Wells, Wallace Bailey, Elijah Prater and John Borders, In 18U0 they became aware that there was another Union Association of United Baptists in Kentucky and added Paint (as they were near Paint Creek) to their name to differentiate between the two groups. -

The History of the Baptists of Tennessee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 6-1941 The History of the Baptists of Tennessee Lawrence Edwards University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, Lawrence, "The History of the Baptists of Tennessee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1941. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2980 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Lawrence Edwards entitled "The History of the Baptists of Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. Stanley Folmsbee, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: J. B. Sanders, J. Healey Hoffmann Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) August 2, 1940 To the Committee on Graduat e Study : I am submitting to you a thesis wr itten by Lawrenc e Edwards entitled "The History of the Bapt ists of Tenne ssee with Partioular Attent ion to the Primitive Bapt ists of East Tenne ssee." I recommend that it be accepted for nine qu arter hours credit in partial fulfillment of the require ments for the degree of Ka ster of Art s, with a major in Hi story. -

The Religious Environment of Lincoln's Youth 25

The Religious Environment of Lincoln’s Youth JOHNF. CADY The religious environment to which Abraham Lincoln was subject as a youth has never been adequately explored. The minute book of the Little Pigeon Baptist Church, although repeatedly examined by biographers, has yielded very little. It is concerned for the most part with purely routine mat- ters such as inquiries into the peace of the church, accept- ance and dismission of members, and the recording of con- tributions of various sorts. Now and then a vote on policy is mentioned, or a matter of discipline raised. Except for the appearance of the Lincoln name at a half dozen or so places, it differs in no important particular from scores of similar records of kindred churches of the period that are available. It is, in fact; less significant than many that the writer has examined. The document acquires meaning only in proportion to one’s understanding of the general situation prevailing among the Regular Baptist churches of Kentucky and Indiana of the time. The discovery of the manuscript minute book of the Little Pigeon Association of United Bap- tists, however, affords a valuable key for relating the Lin- coln church to the larger religious context.’ The fact that the local church was of the Regular Baptist variety while the Association of which it was a member car- ried the name United Baptist requires a word of explanation. Almost all of the early Baptist churches west of the moun- tains accepted the conventional adaptation of the Calvinistic Philadelphia Confession, dating from 1765, practically the only formulated creed available to them.