A PDF Companion to the Audiobook APPENDIX 1: EXPERT CONTRIBUTIONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae Ken Chitwood -June 2020

Curriculum Vitae Ken Chitwood www.kenchitwood.com -June 2020- Education: • University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 2014 - 2019. Ph.D. Religion in the Americas. o Dissertation, “Los Musulmanes Boricuas: Puerto Rican Muslims and the Idea of Cosmopolitanism.” o Graduate Certificate, Global Islamic Studies. • Concordia University, Irvine, CA, 2014. M.A. Theology and Culture (May, 2014). o Thesis, “Islam en Español: The Conversion Pathways of Latina/o Muslims in the U.S.” • Concordia University, Irvine, CA, 2007. B.A. Christian Education Leadership & Theological Studies (May, 2007). Professional Employment: • Fritz Thyssen Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies, Freie Universität Berlin. Berlin, Germany. March 2020 – March 2022. o Conducted research in conjunction with the Graduate School, mentored and worked with graduate students, and participated in the academic life of the Graduate School. • Lecturer, Islamwissenschaft, Otto Friedrich Universität Bamberg. Bamberg, Germany. March 2020 – July 2020. o Delivered lectures and taught a course on Islam and Muslim communities in the Americas. • Journalism Consultant, King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID). Vienna, Austria. February 2020 – December 2020. o Writing and photography/videography for special five year fellowship progress report. • Staff Writer, Religions for Peace, 10th World Assembly of Religions for Peace. Lindau, Germany. July – August 2019. o Working with the established Drafting Committee and the Secretary General of Religions for Peace, I oversaw the writing of the Assembly Declaration, which will guide the focus of the network for the next five years under the theme “Caring for our Common Future.” • Journalist-Fellow, University of Southern California Center for Religion and Civic Culture, Spiritual Exemplars Project. -

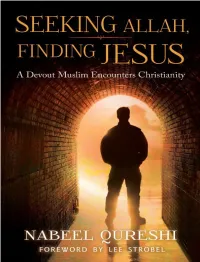

F:\NABEEL QURESHI.Wpd

NABEEL QURESHI The following bio is taken from Dr. Qureshi’s official site: “Dr. Nabeel Qureshi is a former devout Muslim who was convinced of the truth of the Gospel through historical reasoning and a spiritual search for God. Since his conversion, he has dedicated his life to spreading the Gospel through teaching, preaching, writing, and debating. Nabeel has given lectures at universities and seminaries throughout North America, including New York University, Rutgers, the University of North Carolina, the University of Ottawa, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and Biola University. He has participated in 17 moderated, public debates around North America, Europe, and Asia. His focus is on the foundations of the Christian faith and the early history and teachings of Islam. Nabeel is a member of the speaking team at Ravi Zacharias International Ministries. He holds an MD from Eastern Virginia Medical School, an MA in Christian apologetics from Biola University, and an MA from Duke University in Religion.” (In case you didn’t know Dr. Qureshi died of stomach cancer on Sept.16, 2017 at the age of 34.) Wikipedia observes that his first book, Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus, was awarded the Christian Book Award for both “Best New Author” and “Best Non-Fiction” of 2015. Dr. Quershi was the first to earn both honors. They also state that Qureshi lectured to students at more than 100 universities, including Oxford, Columbia, Dartmouth, Cornell, Johns Hopkins, and the University of Hong Kong. He has participated in 18 moderated, public debates around North America, Europe, and Asia. -

Muslim Persecution of Christians

MUSLIM PERSECUTION OF CHRISTIANS By Robert Spencer 1 Muslim Persecution of Christians Copyright 2008 David Horowitz Freedom Center PO Box 55089 “Get out your weapons,” commanded Jaffar Umar Thalib, Sherman Oaks, CA 91423 a 40-year-old Muslim cleric, over Indonesian radio in May (800) 752-6562 2002. “Fight to the last drop of blood.”1 [email protected] The target of this jihad was Indonesian Christians. Christians, Jaffar explained, were “belligerent infidels” www.TerrorismAwareness.org (kafir harbi) and entitled to no mercy. This designation was ISBN # 1-886442-36-3 not merely a stylistic flourish on Jaffar’s part. On the contrary, Printed in the United States of America kafir harbi is a category of infidel that is clearly delineated in Islamic theology. By using this term, Jaffar was not only inciting his followers to violence, but telling them that their actions were theologically sanctioned. Jaffar’s words had consequences. The death toll among Indonesian Christians in the chaos that followed was estimated to be as high as 10,000, with countless thousands more left homeless.2 Journalist Rod Dreher reported in 2002 that Jaffar Umar Thalib’s jihadist group, Laskar Jihad, had also “forcibly converted thousands more, and demolished hundreds of churches.”3 What happened in Indonesia was treated by the international press as an isolated incident. In fact, however, the violent jihad there was part of the ongoing persecution of Christians by Muslims throughout the Islamic world. This violence, reminiscent of barbarous religious conflicts of seven 2 3 hundred years ago, is the dirty little secret of contemporary Boulos’ parish had to denounce the mildly critical remarks religion. -

Nabeel Qureshi April 13, 1983–September 16, 2017

God is our refuge and strength, an ever-present help in trouble. Psalm 46:1 Celebrating the Life of Nabeel Qureshi April 13, 1983–September 16, 2017 The family requests donations to be sent to gofundme.com/NabeelQureshi Order of Service Seating of the family Introduction and Prayer Gregg Matte Senior Pastor Nabeel Qureshi Congregational Worship Great is Thy Faithfulness In Christ Alone On September 16, 2017, heaven welcomed home Dr. Nabeel Asif Qureshi, who passed away in Houston, Texas, at the age of 34. Ever the seeker of truth and knowledge, Nabeel obtained an MD from Eastern Virginia Medical Words of Reflection School, an MA in Christian Apologetics from Biola University, an MA in Dr. James Tour Religion from Duke University, and an MPhil in Judaism and Christianity from Oxford University. A New York Times bestselling author and accomplished speaker, his books Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus, No God But One, and Congregational Worship Answering Jihad continue to touch lives around the world. Ten Thousand Reasons Nabeel’s zeal for ministry and education was surpassed only by his passion for life and love for his family. Those closest to Nabeel will remember Message him for his contagious laughter, his enjoyment of all life had to offer, his Ravi Zacharias tenderness, and his compassion. Nabeel is survived by his parents, Amjad and Sabiha Qureshi; his sister, Scripture Reading Wajiha Mohar; his wife, Michelle; and their 2-year-old daughter, Ayah. and Closing Prayer Psalm 103 Dr. James Tour Worship led by the Houston’s First worship team A viewing and receiving line will take place in the Worship Center following the service. -

KINGDOM KINGDOM Missions and Ministries of the Missions and Ministries of the Baptist General Association of Virginia Baptist General Association of Virginia

stories stories KINGDOM KINGDOM Missions and Ministries of the Missions and Ministries of the Baptist General Association of Virginia Baptist General Association of Virginia BGAV’s Spence Network Spotlights Uptick Alumni BGAV’s Spence Network Spotlights Uptick Alumni The word uptick is defined as a small increase. An uptick in a certain The word uptick is defined as a small increase. An uptick in a certain activity is seen as something making a significant movement. activity is seen as something making a significant movement. Through the Spence Network, the BGAV invests in the “small Through the Spence Network, the BGAV invests in the “small increases” by offering networking and mentoring opportunities to increases” by offering networking and mentoring opportunities to eager and innovative leaders who in turn make an impact on the eager and innovative leaders who in turn make an impact on the local church. local church. Since 2008, 136 young leaders have come through the Uptick Since 2008, 136 young leaders have come through the Uptick program. These members are serving across Virginia, the United program. These members are serving across Virginia, the United States, and as far as Norway. By the end of 2017, the total number States, and as far as Norway. By the end of 2017, the total number of Uptick alumni will increase to 167. of Uptick alumni will increase to 167. Nabeel Qureshi, alumnus of the Uptick class of Nabeel Qureshi, alumnus of the Uptick class of 2011, is a renowned speaker and writer. He wrote 2011, is a renowned speaker and writer. -

The Power of a Personal Testimony Booklet: Increasing Gospel Witness in Everyday Life

Liberty University John W. Rawlings School of Divinity The Power of a Personal Testimony Booklet: Increasing Gospel Witness in Everyday Life A Thesis Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of Liberty School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Department of Evangelism and Church Planting by Patrick Walker Lynchburg, Virginia February 20, 2021 Copyright © 2021 by Patrick Walker All Rights Reserved ii Liberty University John W. Rawlings School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet ___Dr. Daryl Neipp___ Mentor Name & Title __Dr. David Wheeler__ Reader Name & Title iii THE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT ABSTRACT “The Power of a Personal Testimony Booklet: Increasing Gospel Witness in Everyday Life” Patrick Walker Liberty University John W. Rawlings School of Divinity, 2021. Mentor: Dr. Daryl Neipp Evangelism is a key component of the Great Commission and a major responsibility for every Christ-Follower. The practice of personal evangelism, however, is frequently neglected by a majority of Christians. This project will initially examine the current state of personal evangelism in America and the scriptural expectation for all Christians to be frequent communicators of the gospel message. The ultimate purpose of this project is to demonstrate that a member of LivingStone Community Church can increase their Gospel witness in everyday life through the use of a written Personal Testimony Booklet. This pocket-sized booklet consists of two components. The first is a description of the three stages of one’s personal testimony. The second component consists of a unique presentation of the gospel message based upon that person’s spiritual journey. The goal of this thesis will shed light on the value of writing and distributing a personal testimony booklet. -

Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Christ Church 3 Senior Members’ Activities and Publications 107 The Dean 14 News from Old Members 123 The House in 2017 24 The Archives 29 Deceased Members 145 The Cathedral 31 The Cathedral Choir 35 Final Honour Schools 148 The College Chaplain 37 The Development & Graduate Degrees 153 Alumni Office 39 The Library 45 Award of University Prizes 156 The Picture Gallery 49 The Steward’s Dept. 53 Information about Gaudies 158 The Treasury 54 Tutor for Admissions 58 Other Information Junior Common Room 60 Other opportunities to stay Graduate Common Room 62 at Christ Church 160 The Boat Club 65 Conferences at Christ Commemoration Ball 67 Church 161 The Christopher Tower Publications 162 Poetry Prize 69 Cathedral Choir CDs 163 Sports Clubs 71 Sir Michael Dummett Acknowledgements 163 Lecture Theatre 75 Andrea Angel and the Silvertown Explosion 83 Obituaries Dr Paul Kent 85 Bob Jeffery 87 Prof Marilyn Adams 90 Professor David Upton 92 Dr Nabeel Qureshi 96 Sister Mary David Totah 98 Jeremy Goford 101 Geoffrey Harrison 103 1 2 CHRIST CHURCH Visitor HM THE QUEEN Dean Percy, The Very Revd Martyn William, BA Brist, MEd Sheff, PhD KCL. Canons Gorick, The Venerable Martin Charles William, MA (Cambridge), MA (Oxford) Archdeacon of Oxford Biggar, The Revd Professor Nigel John, MA PhD (Chicago), MA (Oxford), Master of Christian Studies (Regent Coll Vancouver) Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology Foot, The Revd Professor Sarah Rosamund Irvine, MA PhD (Cambridge) Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History Ward, The Revd Graham, -

THIRD PARTY CERTIFICATION of FOOD CONTENTS 1 Introduction P1 2 Item A

24 June 2015, on behalf of Richard Sibthorpe, submission to the Senate Economics References Committee for THIRD PARTY CERTIFICATION OF FOOD CONTENTS 1 Introduction p1 2 Item a. submission p2 3 Item b. submission P3 4 Item c. submission P4 5 Item d. submission P4 6 Item e. Submission P5 7 Item f. Submission p6 8 Item g. Submission p7 9 Islam’s Jizya p8 10 My Recommendation p10 11 Conclusion p11 12 Footnotes p12 1 Introduction While this submission is formulated in accordance with the seven line items of enquiry a. to g. which is laid out by the Senate Committee, it specifically relates to the HALAL component referred to in item a. as it is associated with the Islamic religion. In Islam, halal means permitted, licit. My area of major concern is that while this halal matter is an Islamic religious and Sharia Law parameter, nevertheless it has drawn in and thereby directly effects the wider non Islamic community about Australia – yet this vast majority of Australian citizens have not been asked to participate in this Islamic religious exercise, nor do they have any say in this. In its enquiry into this subject area, it is essential that the Senate Committee does recognise and understand the direct connection between the Islamic religion with its divinely specified halal food requirement, and how this requirement directly feeds through to increased food prices for each and every non Muslim citizen in modern Australia. This is the case even though this latter majority has, as I believe, no desirability to understand or adhere to these particular requirements of the Islamic religion. -

Curriculum Vitae Ken Chitwood

Curriculum Vitae Ken Chitwood www.kenchitwood.com Education: • University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 2014 - present. Ph.D. Candidate, Religion in the Americas and Global Islamic Studies. • Concordia University, Irvine, CA, 2014. M.A. Theology and Culture (May, 2014). • Concordia University, Irvine, CA, 2007. B.A. Christian Education Leadership & Theological Studies (May, 2007). Professional Employment: • Program Coordinator, Center for the Humanities and the Public Sphere, University of Florida. Gainesville, FL. February 2018 - present. • Digital Humanities Specialist, University of Florida — Religion Department. Gainesville, FL. February 2015 - present. • LINC Houston, LINC Bible Institute, Director. Houston, TX. September 2010 - November 2012. • Laidlaw College, Adjunct Instructor. Palmerston North, New Zealand. January 2008 - December 2008. Publications: Books Forthcoming: Between Al-Andalus and the Americas. Introducing the Latinx Muslim World. London: Hurst Publishing/Oxford University Press, Spring 2019. A Sacred Duty: A Christian’s Friendly Study of the World’s Religions. Palmerston North, New Zealand: Lutheran Support Ministries, February 2009. Editorial Work Section Editor, “Judaism and Islam in Latin America,” Encyclopedia of Religion in Latin America, ed. by Henri Gooren, (Berlin: Springer References, 2019). Encyclopedia Articles: Multiple entries for “Judaism and Islam in Latin America,” Encyclopedia of Religion in Latin America, ed. by Henri Gooren, (Berlin: Springer References, 2019). “Introduction to the Sociology of Religion,” Gale Researcher: Sociology (February 2017). “The Global Justice Movement,” Gale Researcher: Sociology (February 2017). “Christianity in the U.S.,” Gale Researcher: Sociology (January 2017). “World Religions II: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam,” Gale Researcher: Sociology (January 2017). Journal Publications In review: “The ‘Global War on Terror’ & the Tenuous Public Space of Muslims in Latin America and the Caribbean,” Hamsa Journal of Judaic and Islamic Studies, no. -

Seeking Allah Finding Jesus

Episode 332/333 – Seeking Allah Finding Jesus Seeking Allah Finding Jesus Interview with Nabeel Qureshi Nabeel Qureshi, with a fascinating story of his journey from Islam to faith in Christ, was raised as a devout Muslim in the United States. He grew up studying Islamic apologetics with his family and engaging Christians in religious discussions. But one day, he met a Christian at his university who after one such discussion the two became best friends and began years-long debate on the historical claims of Christianity and Islam. What Accounts For Islam’s Rapid Growth Today? According to Nabeel Qureshi, some studies have been done on this. From a survey within the past few years and also anecdotally, one can get an understanding of the growth rate being primarily by birth rate as Muslims are generally more fertile or producing more children. There were also some conversions. A survey that was done a few years ago indicated that 30,000 people in the United States accept Islam every year. A lot of this has to do with marriage as well as active dawah which is the Islamic form of evangelism where people are being invited to Islam. These account for almost all of the growth of Islam around the world. What Attracts People Especially In The West To Islam? A lot of it has to do with community. If you don’t have a good solid community and you see the way Muslims come together, you’ll notice the sense of solidarity when they pray the five daily prayers. A lot of Muslims actually pray the five daily prayers in congregation as they are supposed to. -

Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus: a Devout Muslim

Nabeel Qureshi first began to study the Bible in order to challenge it and, incredibly, came to know Jesus as a result. I am thrilled to see his unique and gripping story in print and know that you will be encouraged and profoundly challenged by it as well. This is truly a must- read book for our times, as diverse worldviews each must face the test of truth. —Ravi Zacharias, author and speaker This is an urgently needed book with a gripping story. Nabeel Qureshi masterfully argues for the gospel while painting a beautiful portrait of Muslim families and heritage, avoiding the fearmongering and finger-pointing that are all too pervasive in today’s sensationalist world. I unreservedly recommend this book to all. It will feed your heart and mind, while keeping your fingers turning the page! —Josh D. McDowell, author and speaker Nabeel describes the yearning in the hearts of millions of Muslims around the world. This book is a must-read for all seeking to share the hope of Christ with Muslims. —Fouad Masri, President and CEO, Crescent Project Fresh, striking, highly illuminating, and sometimes heartbreaking, Qureshi’s story is worth a thousand textbooks. It should be read by Muslims and all who care deeply about our Muslim friends and fellow citizens. —Os Guinness, author and social critic Nabeel Qureshi’s story is among the most unique two or three testimonies that I have ever heard. His quest brought together several exceptional features: a very bright mind, extraordinary sincerity, original research, and a willingness to follow the evidence trail wherever it took him. -

Protesters Want Police Held Accountable in George Floyd Death the Wired Word for the Week of June 7, 2020

Protesters Want Police Held Accountable in George Floyd Death The Wired Word for the Week of June 7, 2020 In the News Protests have arisen in at least 140 cities across the United States, and in London and Berlin as well, in response to the death of George Floyd, an unarmed African-American man who died while in Minneapolis police custody. Many of the demonstrations have been peaceful, but some have turned into violent clashes. Derek Chauvin, the police officer who kneeled on Floyd's neck for over eight minutes, according to some reports, has been arrested and charged with third-degree murder and manslaughter. In addition, the U.S. Justice Department will launch an investigation into potential violations of federal civil rights laws. In Minneapolis, protesters set fire to a police station as violence spread through the Twin Cities. Dozens of businesses boarded up their windows and doors in attempts to prevent looting. Target, which is based in Minneapolis, temporarily closed two dozen stores, and the city shut down most of its light-rail system and all of its bus service for several days, citing safety concerns. At the same time, thousands of peaceful demonstrators marched through the streets of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, calling for justice. A 20-year-old black woman named Erika Atson was among those who came together for peaceful protest. She told the Associated Press that she had been at "every single protest" since Floyd's death and was worried about raising children who could be vulnerable in encounters with the police.