Religious Minorities and Islamic Law: Accommodation and the Limits of Tolerance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

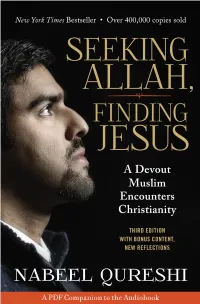

A PDF Companion to the Audiobook APPENDIX 1: EXPERT CONTRIBUTIONS

A PDF Companion to the Audiobook APPENDIX 1: EXPERT CONTRIBUTIONS Growing Up Muslim in America ABDU MURRAY Contributing to Part 1: “Called to Prayer” Abdu Murray is a lawyer, apologist, and former Shia Muslim. Author of two published books on Islam and other major worldviews, he is currently president of Embrace the Truth International. IN THE SALTY-WHITE LANDSCAPE of the Detroit suburb of my youth, my family was a dash of pepper. We stood out because, at that time, we were exotic — one of the few Muslim families in the area. And I took Islam seriously so that I could stand out even more because that would cause my friends to ask questions about my faith. That, in turn, would lead to op- portunities to share what I considered to be the beauty and truth of Islam with the low-hang- ing fruit of the many non-Muslim, mostly Christian, individuals around me. I was like many Muslims I knew. Even as a youth, I loved talking about God and my Islamic faith. I was puzzled that the non-Muslims around me found it so uncomfortable to talk about matters of religion. Don’t these Christians really believe their traditions? If their message is true, why are they so afraid to talk about it? The answer, I told myself, is that Christians know deep down that their religion is silly. They only need to be shown the truth of Islam to see the true path. Muslims get that kind of confidence from religious training received during their child- hood and teen years. -

JESUS, the QĀ'im and the END of the WORLD Author(S): Gabriel Said Reynolds Source: Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, Vol

Sapienza - Universita di Roma JESUS, THE QĀ'IM AND THE END OF THE WORLD Author(s): Gabriel Said Reynolds Source: Rivista degli studi orientali, Vol. 75, Fasc. 1/4 (2001), pp. 55-86 Published by: Sapienza - Universita di Roma Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41913072 Accessed: 16-04-2016 02:00 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Sapienza - Universita di Roma, Fabrizio Serra Editore are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Rivista degli studi orientali This content downloaded from 129.81.226.78 on Sat, 16 Apr 2016 02:00:42 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms m JESUS, THE QÄ'IM AND THE END OF THE WORLD1 The goal of this paper is to address an intriguing aspect of Islamic religious development, which, to my knowledge, has thus far gone unmentioned by we- stern scholars. Our task can be described quite succinctly: the Jesus of SunnI Islam is a uniquely charismatic prophet, whose life is framed by two extraordi- nary events: his miraculous birth and his return in the end times to defeat evil and establish the universal rule of Islam. -

View/Print Page As PDF

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds The Vocabulary of Sectarianism by Aaron Y. Zelin, Phillip Smyth Jan 29, 2014 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Aaron Y. Zelin Aaron Y. Zelin is the Richard Borow Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy where his research focuses on Sunni Arab jihadi groups in North Africa and Syria as well as the trend of foreign fighting and online jihadism. Phillip Smyth Phillip Smyth was a Soref Fellow at The Washington Institute from 2018-2021. Articles & Testimony Many players in Syria are pursuing a long-term sectarian dehumanization strategy because they view the war as an existential religious struggle between Sunnis and Shiites, indicating that peace conferences are unlikely to resolve the conflict. s the conflict in Syria continues to spread throughout the Levant and adopt a broader sectarian tone -- Sunni A Salafis on one side and Iranian-backed, ideologically influenced Shiite Islamists on the other -- it is important to know how the main actors have cast one another. Unlike the rhetoric during the Iraq War (2003), sectarian language on both sides is regularly finding its way into common discourse. Fighting between Sunnis and Shiites has picked back up in Iraq, is slowly escalating in Lebanon, and there have been incidents in Australia, Azerbaijan, Britain, and Egypt. The utilization of these words in militant and clerical lingo reflects a broader and far more portentous shift: A developing sectarian war and strategy of dehumanization. This is not simply a representation of petty tribal hatreds or a simple reflection on Syria's war, but a grander regional and religious issue. -

Using Blockchain in WAQF, Wills and Inheritance Solutions in the Islamic System Submitted 15/03/21, 1St Revision 12/04/21, 2Nd Revision 30/04/21, Accepted 25/05/21

International Journal of Economics and Business Administration Volume IX, Issue 2, 2021 pp. 101-116 Using Blockchain in WAQF, Wills and Inheritance Solutions in the Islamic System Submitted 15/03/21, 1st revision 12/04/21, 2nd revision 30/04/21, accepted 25/05/21 Walaa J. Alharthi1 Abstract: Purpose: The paper aims to provide a review of literature on the Islamic social institution of WAQF, dissecting the components of WAQF and the classic Islamic laws that guide its formation and implementation. WAQFs are Islamic social finance institutions that have played a critical role in achieving sustainable development in Islamic society. During the Ottoman era, it was operated effectively to ensure the founder's wishes until the advent of Islamic finance. The study highlights the challenges that the WAQF institution faces and the viability of the Blockchain system in mitigating these challenges and managing WAQF across the globe, which should help achieve the convectional objectives WAQF. Approach/Methodology/Design: The study reviewed the most recent research papers on the WAQF Islamic social finance institution to isolate the institution's components, legal framework and challenges, and outline the solutions Blockchain system can provide. Findings: The study shows that the main challenge obstructing the rejuvenation of the WAQF system to its lost glory has been lack of data, compromised historical records in the event of the Founders' demise, lack of transparency, and inappropriate auditing. Through smart contracts on Blockchain, there is a surety of efficacy and effective performance of WAQF institution and the realization of the founders' objectives. Practical Implications: The study will contribute positively to understanding the historical importance of WAQF as an Islamic social institution and a predecessor to Islamic finance for academia and the possibility of utilizing Blockchain systems in managing WAQF transactions across the globe. -

62 of 17 January 2018 Replacing Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council

23.1.2018 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 18/1 II (Non-legislative acts) REGULATIONS COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) 2018/62 of 17 January 2018 replacing Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2005 on maximum residue levels of pesticides in or on food and feed of plant and animal origin and amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC (1), and in particular Article 4 thereof, Whereas: (1) The products of plant and animal origin to which the maximum residue levels of pesticides (‘MRLs’) set by Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 apply, subject to the provisions of that Regulation, are listed in Annex I to that Regulation. (2) Additional information should be provided by Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 as regards the products concerned, in particular as regards the synonyms used to indicate the products, the scientific names of the species to which the products belong and the part of the product to which the respective MRLs apply. (3) The text of footnote (1) in both Part A and Part B of Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 should be reworded, in order to avoid ambiguity and different interpretations encountered with the current wording. (4) New footnotes (3) and (4) should be inserted in Part A of Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005, in order to provide additional information as regards the part of the product to which the MRLs of the products concerned apply (5) New footnote (7) should be inserted in Part A of Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005, in order to clarify that MRLs of honey are not applicable to other apiculture products due to their different chemicals character istics. -

Millions of Muslims Arrive in Mecca for Haj

4 September 11, 2016 Cover Story Gulf Millions of Muslims arrive in Mecca for haj Muslim pilgrims prepare for Friday prayers in front of the Kaaba, Islam’s holiest shrine, at the Grand Mosque in the Muslim holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia, on September 9th. The Arab Weekly staff dom, passport officials said, and the pilgrimage, the Ministry of Haj kingdom to help pilgrims. More than 100,000 troops were were sent back to respective coun- is addressing the potential for heat- The Grand Mosque’s security deployed in Mecca and 4,500 Saudi tries due to violations, which in- related health problems with doc- forces completed preparations for Boy Scouts volunteered to assist Jeddah cluded 52 forged passports. tors from the King Abdullah Medical the haj and appear to have incorpo- pilgrims in Mecca and visitors to the Saudi authorities, with an eye to City using state-of-the-art cooling rated a new security plan, according Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. he annual haj officially tragic accidents last year in which vests designed to treat heatstroke to Commander of Task Force for the The fifth pillar of Islam, haj is a began on September 10th, hundreds died, have taken the se- for the first time during thehaj . Security of the Grand Mosque Ma- ritual Muslims should perform at drawing an estimated 2 curity and safety of haj pilgrims to jor-General Mohammed al-Harbi. least once in their lifetime. To per- million Muslims from 180 new heights in terms of planning, The Saudi Ministry of Harbi, at a news conference in form the rite, one must be an adult countries to Mecca to per- safety and the use of the latest tech- Health stationed more Mina, said: “The plan of the Grand Muslim with a sound mind and the Tform the five-day rituals considered nologies to ensure the well-being of Mosque’s security force was built physical ability to perform the ritu- than 26,000 medical one the five main pillars of Islam. -

The Grading of Waqf System in Eighteenth-Century Istanbul in Light of Istanbul Ahkâm Registers (1750-1762) M

M. Burak BULUTTEKİN THE GRADING OF WAQF SYSTEM IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ISTANBUL IN LIGHT OF ISTANBUL AHKÂM REGISTERS (1750-1762) M. Burak BULUTTEKİN ABSTRACT This study, which aims to evaluate the waqf (vakıf, charitable endowments) system of Istanbul in the eighteenth-century, is based on the grading of Istanbul Ahkâm Registers in the period of 1750-1762. In order to classify the provisions of Ahkâm Registers; (a) registry (book) numbers, (b) application areas, (c) conflict issues, (d) the social position of the litigants, (e) the religion of the litigants, and (f) application years were chosen as the basic analysis variables. Each judgement, which were based on this systematic, were examined in themselves. 192 provisions of the waqf system were determined in Istanbul Ahkâm Registers in the period of January 1750-December 1762. The analysis of this Ahkâm Books (between 3-6 books), the maximum provisions were found with 3rt part (29.7%) of them. The most problems of the waqf system of Istanbul were “revenue and accounting of the waqf” (62%), “using, devolution and istibdal (exchanging) of the waqf’s place” (60.4%) and “lease of the waqf, rental procedures and tenancy” (45.8%). Moreover, the most waqf’s problems occurred in Surici (64.1%) region. Also, the most waqf system problem in Surici and Uskudar was “istibdal (exchanging)”(respectively 95 and 10 cases) and in Haslar and Galata was “intermeddling, suppression or occupancy to the waqf’s place” (respectively 13 and 4cases). The waqf system problems of Istanbul in the eighteenth-century mostly occurred between the reaya (92.2%). -

Role of Zakah and Awqaf in Poverty Alleviation

Islamic Development Bank Group Islamic Research & Training Institute Role of Zakah and Awqaf in Poverty Alleviation Habib Ahmed Occasional Paper No. 8 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia b © Islamic Development Bank, 2004 Islamic Research and Training Institute, King Fahd National Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ahmed, Habib Role of Zakat and Awqaf in Poverty Alleviation./ Habib Ahmed- Jeddah,2004-08-03 150 P; 17X 24 cm ISBN: 9960-32-150-9 1-Zakat 2-Endownments (Islamic fiqh) 3- Waqf I-Title 252.4 dc 1425/4127 L.D. No. 1425/4127 ISBN: 9960-32-150-9 The views expressed in this book are not necessarily those of the Islamic Research and Training Institute or of the Islamic Development Bank. References and citations are allowed but must be properly acknowledged First Edition 1425H (2004) . c ﺑﺴﻢ ﺍﻪﻠﻟ ﺍﻟﺮﲪﻦ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻴﻢ BISMILLAHIRRAHMANIRRAHIM d e CONTENTS List of Tables, Charts, Boxes, and Figures……………………….. 5 Acknowledgements..................................................................................... 9 Foreword……………………………………………………………………. 13 Executive Summary…………………………………………………… 15 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………… 19 1.1. Islamic View of Poverty……………………………………….. 20 1.2. Objectives of the Paper………………………………………… 23 1.3. Outline of the Paper……………………………………………. 23 2. Shari[ah and Historical Aspects of Zakah and Awqaf……... 25 2.1. Zakah and Awqaf in Shari[ah and Fiqh ……………………. 25 2.1.1. Zakah in Shari[ah and Fiqh………………………… 25 2.1.2. Awqaf in Shari[ah and Fiqh ………………………… 28 2.2. Historical Experiences of Zakah and Awqaf………………. 30 2.2.1. Historical Experiences of Zakah…………………….. 30 2.2.2. Historical Experiences of Awqaf…………………….. 32 2.3. Contemporary Resolutions on Zakah and Awqaf………… 35 2.3.1. Contemporary Resolutions on Zakah………………. -

TOCQUEVILLE in the OTTOMAN EMPIRE the OTTOMAN EMPIRE and ITS HERITAGE Politics, Society and Economy

TOCQUEVILLE IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE AND ITS HERITAGE Politics, Society and Economy edited by Suraiya Faroqhi and Halil Inalcik Advisory Board Fikret Adanir • Idris Bostan • Amnon Cohen • Cornell Fleischer Barbara Flemming • Alexander de Groot • Klaus Kreiser Hans Georg Majer • Irène Mélikoff • Ahmet Yas¸ar Ocak Abdeljelil Temimi • Gilles Veinstein • Elizabeth Zachariadou VOLUME 28 TOCQUEVILLE IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE Rival Paths to the Modern State BY ARIEL SALZMANN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on http://catalog.loc.gov ISSN 1380-6076 ISBN 90 04 10887 4 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, Rosewood Drive 222, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands SALZMAN_f1-v-xv 11/12/03 11:08 AM Page v v To my mother and father This page intentionally left blank SALZMAN_f1-v-xv 11/12/03 11:08 AM Page vii vii CONTENTS List of Illustrations ...................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................ xi List of Abbreviations .................................................................. xiii Note on Transliteration ............................................................ xv Introduction: Tocqueville’s Ghost .................................................. 1 In Search of an Archive ................................................... -

Muslim Persecution of Christians

MUSLIM PERSECUTION OF CHRISTIANS By Robert Spencer 1 Muslim Persecution of Christians Copyright 2008 David Horowitz Freedom Center PO Box 55089 “Get out your weapons,” commanded Jaffar Umar Thalib, Sherman Oaks, CA 91423 a 40-year-old Muslim cleric, over Indonesian radio in May (800) 752-6562 2002. “Fight to the last drop of blood.”1 [email protected] The target of this jihad was Indonesian Christians. Christians, Jaffar explained, were “belligerent infidels” www.TerrorismAwareness.org (kafir harbi) and entitled to no mercy. This designation was ISBN # 1-886442-36-3 not merely a stylistic flourish on Jaffar’s part. On the contrary, Printed in the United States of America kafir harbi is a category of infidel that is clearly delineated in Islamic theology. By using this term, Jaffar was not only inciting his followers to violence, but telling them that their actions were theologically sanctioned. Jaffar’s words had consequences. The death toll among Indonesian Christians in the chaos that followed was estimated to be as high as 10,000, with countless thousands more left homeless.2 Journalist Rod Dreher reported in 2002 that Jaffar Umar Thalib’s jihadist group, Laskar Jihad, had also “forcibly converted thousands more, and demolished hundreds of churches.”3 What happened in Indonesia was treated by the international press as an isolated incident. In fact, however, the violent jihad there was part of the ongoing persecution of Christians by Muslims throughout the Islamic world. This violence, reminiscent of barbarous religious conflicts of seven 2 3 hundred years ago, is the dirty little secret of contemporary Boulos’ parish had to denounce the mildly critical remarks religion. -

Shedding Light on the Modalities of Authority in a Dar Al-Uloom, Or Religious Seminary, in Britain

religions Article Shedding Light on the Modalities of Authority in a Dar al-Uloom, or Religious Seminary, in Britain Haroon Sidat Centre for the Study of Islam in the UK, School of History, Archaeology and Religion, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3EU, UK; Sidathe@cardiff.ac.uk Received: 25 July 2019; Accepted: 26 November 2019; Published: 29 November 2019 Abstract: ‘God is the Light of the heavens and the earth ::: ’ (Quran, 24:35.) This article sheds light on the modalities of authority that exist in a traditional religious seminary or Dar al-Uloom (hereon abbreviated to DU) in modern Britain. Based on unprecedented insider access and detailed ethnography, the paper considers how two groups of teachers, the senior and the younger generation, acquire and shine their authoritative light in unique ways. The article asserts that within the senior teachers an elect group of ‘luminaries’ exemplify a deep level of learning combined with practice and embodiment, while the remaining teachers are granted authority by virtue of the Prophetic light, or Hadith, they radiate. The younger generation of British-born teachers, however, are the torchbearers at the leading edge of directing the DU. While it may take time for them to acquire the social and symbolic capital of the senior teachers, operationally, they are the ones illuminating the way forward. The paper discusses the implications of the changing nature of authority within the DU is likely to have for Muslims in Britain. Keywords: Dar al-Uloom; Islam in Britain; Deoband; ulama; tradition; authority 1. Introduction During research undertaken for my PhD thesis, authority emerged as a significant analytical category and became one of the lenses through which I examined the Dar al-Uloom (DU).1 Its relationship with the Islamic tradition, that of being anchored in an authentic past, results in intense competition among British Muslims who vie to present themselves as heirs of an authentic interpretation and practice of Islam (Gilliat-Ray 2010). -

The Dhimmis and Their Role in the Administration of the Fatimid State

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 2; February 2016 The Dhimmis and their Role in the Administration of the Fatimid State Dr. Saleh Kharanbeh Lecturer of Arabic language and Islamic studies Ohalo College of Education Israel Dr. Muhammad Hamad Lecturer of Arabic language and literature Al- Qasemi College of Education Israel Abstract One of the most recurring questions today is the Islamic state's relationship with the dhimmis (Jews and Christians living under early Muslim rule) and their status in the early days of Islam and up to the late days of the Islamic Caliphate. This relationship may have been varying, swinging up and down. Perhaps the more legitimate questions are: What were the factors that affected the nature of the Dhimmis relationship with the ruling power in the Islamic state? What was the status of the Dhimmis and what roles did they play in the early Islamic states, with the Fatimid Caliphate as a model? The Fatimid Caliphate rose up and centered in Egypt, which was then home for Coptic Christians and Jews, living side by side with Muslims. That is why the author has chosen the Fatimid State, in specific. Another driver for this selection is the fact that when the Fatimid Caliphate was ruling in Egypt, the Europeans were launching their Crusades in Jerusalem, which placed such a relationship between Muslims and Christians at stake. Keywords: The Dhimmis, Fatimid State, Islamic history, Islamic civilization. 1. Internal factors in the Dhimmis relationship with the Fatimid Caliphate The caliphs’ young age was one of the factors that contributed to strengthening the relationship between the Dhimmis and the ruling power.