The Oldest Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019–2023 Port Development Plan Contents

2019–2023 PORT DEVELOPMENT PLAN CONTENTS Port Development Plan 2019–2023 1 Purpose of This Plan 2 8 Port Kembla Development Plan 44 Port Kembla Overview 46 2 The Value of Our Ports 4 Port Kembla Key Strengths and Advantages 47 Our Economic Contribution 6 Port Kembla Planning Framework 52 Sydney Household Goods Imported Road and Rail Access 52 Through Port Botany 7 Future Development 53 Quay Conclusions 8 Priority supporting infrastructure improvements The Quay Conclusions report found that: 9 (by others) 55 3 Our Role 10 9 Enfield and Cooks River Development Plan 56 4 Our Strategic Objectives 12 Enfield Intermodal Logistics Centre Overview 58 Enfield Intermodal Logistics Centre 5 What We’ve Achieved: 2013–2018 14 Key Strengths and Advantages 59 Cooks River Intermodal Terminal Overview 60 Cooks River Key Strengths and Advantages 61 6 Sustainability 22 Intermodal Terminal Planning Framework 62 Environmental Management and Community Road and Rail 62 Engagement 24 Future Development 63 Port Botany Community Consultative Committee 26 Priority supporting infrastructure improvements Port Kembla Harbour Environment Group 26 (by others) 65 Enfield Community Liaison Committee 26 Sustainability Highlights 28 10 Implementing the Port Development Plan 66 7 Port Botany Development Plan 30 Port Botany Overview 32 Port Botany Key Strengths and Advantages 33 Port Botany Planning Framework 36 Road and Rail Access 37 Future Development 41 Priority supporting infrastructure improvements (by others) 43 NSW Ports | Port Development Plan 2019–2023 1 1 PURPOSE OF THIS PLAN 2 NSW Ports | Port Development Plan 2019–2023 PURPOSE OF THIS PLAN This Port Development Plan 2019–2023 identifies the development objectives and proposals for NSW Ports’ assets of Port Botany, Port Kembla, the Enfield Intermodal Logistics Centre (Enfield ILC) and Cooks River Intermodal Terminal. -

Visual Pilot Guide 2010

SYDNEY BASIN VISUAL PILOT GUIDE 2010 VISUAL PILOT GUIDE 2010 SYDNEY VPG 2010.indd 1 12/14/10 9:22 AM CASA’S VISUAL PILOT GUIDES – the pilot’s must have As a visual pilot, you are encouraged to use this visual pilot guide (VPG) for planning flights in the class D and non-towered environment. In doing this, you will join thousands of pilots who have benefited from the information these guides provide. Since the VPGs were introduced in 1998, they have become an integral part of the visual pilot’s flight bag. Originally developed in response to the rising number of violations of controlled airspace in the Brisbane area, their popularity grew to the point that CASA decided to produce them for all the former GAAP aerodromes. They undergo a process of continual improvement made possible only through feedback from industry, and the dedication of a number of industry participants. The VPGs are a must-have item for any pilot wishing to fly into or out of the featured aerodromes. NOTE: The information contained in this guide was correct at the time of publishing, and is subject to change without notice. CASA makes no representation as to its accuracy. It has been prepared by CASA Safety Promotion for information purposes only. Plan your route thoroughly, and carry current charts and documents. Always check ERSA, NOTAMs, and the weather, BEFORE you fly. The VPGs do not replace current operational maps and charts. © 2010 Civil Aviation Safety Authority Australia The Visual Pilot Guide (VPG) is an aid for pilots to use when flying into, out of and around Sydney aerodromes. -

Stanwell Park to Wollongong

Stanwell Park to 2 Wollongong Bus Timetable via Wombarra, Coledale, Austinmer, Thirroul, Corrimal & Fairy Meadow Includes accessible services Effective from 29 January 2013 What’s inside Opal. Your ticket to public transport. Your Bus timetable ........................................................... 1 Opal is the easy way of travelling on public transport in Ticketing .......................................................................... 1 Sydney, the Blue Mountains, Central Coast, Hunter, Illawarra and Southern Highlands. Accessible services ............................................................ 1 An Opal card is a smartcard you keep and reuse. You load How to use this timetable ................................................. 2 value onto the card to pay for your travel on any mode of Other general information ................................................. 2 public transport, including trains, buses, ferries and light rail. Bus contacts ..................................................................... 3 Opal card benefits Timetables • Fares capped daily, weekly and on Sundays* From Stanwell Park towards Wollongong • Discounted travel after eight paid journeys each week Monday to Friday ............................................................. 4 • $2 discount for every transfer between modes (train, bus, ferry, light rail) as part of one journey within 60 minutes.† Saturday .......................................................................... 6 • Off-peak train fare savings of 30% From Wollongong towards -

Illawarra Business Chamber/Illawarra First

Illawarra Business Chamber/Illawarra First Inquiry into Regional Development and Decentralisation Submission to the Select Committee on Regional Development and Decentralisation SUBMISSION – Inquiry into Regional Development and Decentralisation SUBMISSION – Inquiry into Regional Development and Decentralisation Contents 1. Introduction .........................................................................................................................................1 2. Background ..........................................................................................................................................1 2.1 Illawarra Business Chamber/Illawarra First .........................................................................................1 2.2 Overview of the Illawarra ....................................................................................................................1 3. Approaches to Regional Development ................................................................................................2 3.1 Best practice in regional development ................................................................................................2 3.2 Focus on Competitive Advantages .......................................................................................................3 3.3 Realising benefits of proximity to Sydney ............................................................................................3 3.4 Importance of transport connectivity to regional economies .............................................................4 -

The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839

University of Wollongong Research Online Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Chancellor (Education) - Papers Chancellor (Education) 1-9-1988 The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839 Michael K. Organ University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Organ, Michael K.: The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839 1988. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/34 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839 Abstract Jane Franklin, the wife of Sir John Franklin, Governor of Tasmania, travelled overland from Port Phillip to Sydney in 1839. During the trip she kept detailed diary notes and wrote a number of letters. Between 10-17 May 1839 she journeyed to the Illawarra region on the coast of New South Wales. A transcription of the original diary notes is presented, along with descriptive introduction to the life and times of Jane Franklin. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Social and Behavioral Sciences Publication Details This booklet was originally published as Organ, M (ed), The Illawarra Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 10-17 May 1839, Illawarra Historical Publications, 1988, 51p. This book is available at Research Online: -

Campbelltown Local Government Area Heritage Review for Campbelltown

CAMPBELLTOWN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA HERITAGE REVIEW FOR CAMPBELLTOWN CITY COUNCIL VOLUME 1: REPORT APRIL 2011 Section 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CONTENTS Page 1 Executive summary ...................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction .................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Background ....................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Report structure ................................................................................................. 3 2.3 The study area ................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Sources ............................................................................................................. 8 2.5 Method .............................................................................................................. 8 2.6 Limitations ......................................................................................................... 9 2.7 Background to the investigation of potential heritage items ................................ 9 2.8 Author Identification ......................................................................................... 10 2.9 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 10 3 Historical Context of the Campbelltown LGA ............................................. 11 3.1 Sources and background -

Strategic Planning for the Future

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Coal Operators' Conference Sciences 2004 Strategic Planning for the Future B. Allan BHP Billiton - Illawarra Coal Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/coal Part of the Engineering Commons Recommended Citation B. Allan, Strategic Planning for the Future, in Naj Aziz and Bob Kininmonth (eds.), Proceedings of the 2004 Coal Operators' Conference, Mining Engineering, University of Wollongong, 18-20 February 2019 https://ro.uow.edu.au/coal/123 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] 2004 Coal Operators’ Conference The AusIMM Illawarra Branch KEYNOTE ADDRESS STRATEGIC PLANNING FOR THE FUTURE Bruce Allan 1 INTRODUCTION Planning and development for both new and existing coal mines is a major process that has increased in complexity from one involving a small number of stakeholders that were primarily focused on the broad issues of: • Resource • Technical process • Market • Business result to one today which is quite complex, involving many internal studies, corporate checks and balances, expert consultant studies and many stakeholders both small and large, government and non-government. The aim of this AUSIMM 2004 Conference and Workshop is to bring together expert speakers who will seek to highlight and share some of their experiences of issues and aspects which impact on coal mine planning and development – both now and into the future. In any business project or venture, and coal mining is no different, it is important to clearly understand all issues that will impact on a project and its viability and have in place appropriate strategies to manage and ensure the successful outcome of all goals that are set. -

Walks, Paddles and Bike Rides in the Illawarra and Environs

WALKS, PADDLES AND BIKE RIDES IN THE ILLAWARRA AND ENVIRONS Mt Carrialoo (Photo by P. Bique) December 2012 CONTENTS Activity Area Page Walks Wollongong and Illawarra Escarpment …………………………………… 5 Macquarie Pass National Park ……………………………………………. 9 Barren Grounds, Budderoo Plateau, Carrington Falls ………………….. 9 Shoalhaven Area…..……………………………………………………….. 9 Bungonia National Park …………………………………………………….. 10 Morton National Park ……………………………………………………….. 11 Budawang National Park …………………………………………………… 12 Royal National Park ………………………………………………………… 12 Heathcote National Park …………………………………………………… 15 Southern Highlands …………………………………………………………. 16 Blue Mountains ……………………………………………………………… 17 Sydney and Campbelltown ………………………………………………… 18 Paddles …………………………………………………………………………………. 22 Bike Rides …………………………………………………………………………………. 25 Note This booklet is a compilation of walks, paddles, bike rides and holidays organised by the WEA Illawarra Ramblers Club over the last several years. The activities are only briefly described. More detailed information can be sourced through the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, various Councils, books, pamphlets, maps and the Internet. WEA Illawarra Ramblers Club 2 October 2012 WEA ILLAWARRA RAMBLERS CLUB Summary of Information for Members (For a complete copy of the “Information for Members” booklet, please contact the Secretary ) Participation in Activities If you wish to participate in an activity indicated as “Registration Essential”, contact the leader at least two days prior. If you find that you are unable to attend please advise the leader immediately as another member may be able to take your place. Before inviting a friend to accompany you, you must obtain the leader’s permission. Arrive at the meeting place at least 10 minutes before the starting time so that you can sign the Activity Register and be advised of any special instructions, hazards or difficulties. Leaders will not delay the start for latecomers. -

D193 Robert T. C. Jones Photograph Collection

University of Wollongong Archives (WUA) D Collections D193 Robert T.C. Jones Photograph Collection Creator: Robert Trevis Clifford Jones Historical Note: Mr Robert (Bob) Jones, of Bulli, was born in 1909. His family were long time residents of the Bulli district, and were associated with timber getting. He donated the collection to the University in 1994. It comprises photographs, the majority copies of originals, focusing on the Bulli district and the northern suburbs of the Illawarra, as well as several other locations from around New South Wales and overseas. Record Summary: Personal records – Photographic prints [majority are copies of originals] majority black & white, some coloured, negatives, plus two audio cassette tapes Date Range: 1880s-1980s Quantity: 45cm (3 boxes) (1066 items) Access Conditions: Available for reference. Contact Archivist in advance to arrange access. Note: Photographs arranged in folders according to subject. Inventory: Originally compiled 31 May 1995. Last revised April 2014. Page 1 of 27 University of Wollongong Archives (WUA) D Collections D193 Robert T.C. Jones Photograph Collection Series List Folder Items Description / Subject 1. 1-49 Wollongong 2. 1-25 Woonona/ Bellambi/ Russell Vale 3. 1-101 Bulli 4. 1-66 Bulli Pass 5. 1-84 Thirroul 6. 1-14 Austinmer 7. 1-10 Coalcliff 8. 1-28 Coledale 9. 1-17 Stanwell Park 10. 1-9 Lodden Falls 11. 1-62 Sherbrooke/ Cataract Dam 12. 1-27 Illawarra 13. 1-39 Blue Mountains 14. 1-22 National Park 15. 1-85 Sydney 16. 1-37 Sydney 17. 1-22 Aboriginal 18. 1-56 Railways 19. 1-20 World War I- Middle East 20. -

A History of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before Colonisation

University of Wollongong Research Online Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Senior Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Deputy Vice- Chancellor (Education) - Papers Chancellor (Education) 1-1-2015 A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation Mike Donaldson University of Wollongong, [email protected] Les Bursill University of Wollongong Mary Jacobs TAFE NSW Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Donaldson, Mike; Bursill, Les; and Jacobs, Mary: A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation 2015. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/581 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A history of Aboriginal Illawarra Volume 1: Before colonisation Abstract Twenty thousand years ago when the planet was starting to emerge from its most recent ice age and volcanoes were active in Victoria, the Australian continent’s giant animals were disappearing. They included a wombat (Diprotodon) seen on the right, the size of a small car and weighing up to almost three tons, which was preyed upon by a marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) on following page. This treedweller averaging 100 kilograms, was slim compared to the venomous goanna (Megalania) which at 300 kilograms, and 4.5 metres long, was the largest terrestrial lizard known, terrifying but dwarfed by a carnivorous kangaroo (Propleopus oscillans) which could grow three metres high. Keywords before, aboriginal, colonisation, 1:, history, volume, illawarra Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Social and Behavioral Sciences Publication Details Bursill, L., Donaldson, M. -

Early Roads on Bulli Mountain

78 NOV /DEC 2005 Illawarra Historical Society Inc. The following article was written by Mr W A Bayley for the Bulletin in 1960. Early Roads on Bulli Mountain During the years in which the coal trade grew saw also the growth of the district, both commercially and socially, as one by one the various villages appeared with the opening of the mines, and the roads developed to link the district overland with Sydney, with which it had also been linked for over half a century by the seaway. Bulli was brought into prominence in the ' forties' (1840s) with the opening of the mountain passes for traffic. Surveyor Burnett in 1841 found tracks from Appin to the coast being used regularly. In 1844 Captain Westmacott, who had secured land from O'Brien at Bulli, where he resided, found another route up Bulli Mountain. It began just west of his own house and followed westwards up the ridge still used for Bulli Pass, but instead of turning south and proceeding to the Elbow as the Pass does today, it turned slightly north-west and made almost straight up the mountainside, as is shown on the Wonona Parish Map to this day. The cost of clearing the road was paid for with money collected from settlers, and soon became the most favoured track used by horsemen from Wollongong to Sydney, although the "Illawarra Hill" as the Pass was called, was considered difficult. That bridle track was the forerunner of the famous Bulli Pass, the lower half of it remaining on much the same route after one hundred years. -

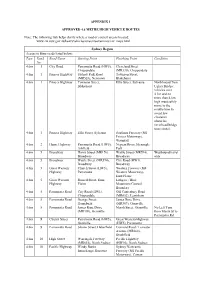

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The

APPENDIX 1 APPROVED 4.6 METRE HIGH VEHICLE ROUTES Note: The following link helps clarify where a road or council area is located: www.rta.nsw.gov.au/heavyvehicles/oversizeovermass/rav_maps.html Sydney Region Access to State roads listed below: Type Road Road Name Starting Point Finishing Point Condition No 4.6m 1 City Road Parramatta Road (HW5), Cleveland Street Chippendale (MR330), Chippendale 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Sydney Park Road Townson Street, (MR528), Newtown Blakehurst 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Townson Street, Ellis Street, Sylvania Northbound Tom Blakehurst Ugly's Bridge: vehicles over 4.3m and no more than 4.6m high must safely move to the middle lane to avoid low clearance obstacles (overhead bridge truss struts). 4.6m 1 Princes Highway Ellis Street, Sylvania Southern Freeway (M1 Princes Motorway), Waterfall 4.6m 2 Hume Highway Parramatta Road (HW5), Nepean River, Menangle Ashfield Park 4.6m 5 Broadway Harris Street (MR170), Wattle Street (MR594), Westbound travel Broadway Broadway only 4.6m 5 Broadway Wattle Street (MR594), City Road (HW1), Broadway Broadway 4.6m 5 Great Western Church Street (HW5), Western Freeway (M4 Highway Parramatta Western Motorway), Emu Plains 4.6m 5 Great Western Russell Street, Emu Lithgow / Blue Highway Plains Mountains Council Boundary 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road City Road (HW1), Old Canterbury Road Chippendale (MR652), Lewisham 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road George Street, James Ruse Drive Homebush (MR309), Granville 4.6m 5 Parramatta Road James Ruse Drive Marsh Street, Granville No Left Turn (MR309), Granville