First Steps in Perl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executable Code Is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law a Retrospective Criticism of Technical and Legal Naivete in the Apple V

Executable Code is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law A retrospective criticism of technical and legal naivete in the Apple V. Franklin case Matthew M. Swann, Clark S. Turner, Ph.D., Department of Computer Science Cal Poly State University November 18, 2004 Abstract: Copyright was created by government for a purpose. Its purpose was to be an incentive to produce and disseminate new and useful knowledge to society. Source code is written to express its underlying ideas and is clearly included as a copyrightable artifact. However, since Apple v. Franklin, copyright has been extended to protect an opaque software executable that does not express its underlying ideas. Common commercial practice involves keeping the source code secret, hiding any innovative ideas expressed there, while copyrighting the executable, where the underlying ideas are not exposed. By examining copyright’s historical heritage we can determine whether software copyright for an opaque artifact upholds the bargain between authors and society as intended by our Founding Fathers. This paper first describes the origins of copyright, the nature of software, and the unique problems involved. It then determines whether current copyright protection for the opaque executable realizes the economic model underpinning copyright law. Having found the current legal interpretation insufficient to protect software without compromising its principles, we suggest new legislation which would respect the philosophy on which copyright in this nation was founded. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 THE ORIGIN OF COPYRIGHT ........................................................................... 1 The Idea is Born 1 A New Beginning 2 The Social Bargain 3 Copyright and the Constitution 4 THE BASICS OF SOFTWARE .......................................................................... -

PHP Programming Cookbook I

PHP Programming Cookbook i PHP Programming Cookbook PHP Programming Cookbook ii Contents 1 PHP Tutorial for Beginners 1 1.1 Introduction......................................................1 1.1.1 Where is PHP used?.............................................1 1.1.2 Why PHP?..................................................2 1.2 XAMPP Setup....................................................3 1.3 PHP Language Basics.................................................5 1.3.1 Escaping to PHP...............................................5 1.3.2 Commenting PHP..............................................5 1.3.3 Hello World..................................................6 1.3.4 Variables in PHP...............................................6 1.3.5 Conditional Statements in PHP........................................7 1.3.6 Loops in PHP.................................................8 1.4 PHP Arrays...................................................... 10 1.5 PHP Functions.................................................... 12 1.6 Connecting to a Database............................................... 14 1.6.1 Connecting to MySQL Databases...................................... 14 1.6.2 Connecting to MySQLi Databases (Procedurial).............................. 14 1.6.3 Connecting to MySQLi databases (Object-Oriented)............................ 15 1.6.4 Connecting to PDO Databases........................................ 15 1.7 PHP Form Handling................................................. 15 1.8 PHP Include & Require Statements......................................... -

Studying the Real World Today's Topics

Studying the real world Today's topics Free and open source software (FOSS) What is it, who uses it, history Making the most of other people's software Learning from, using, and contributing Learning about your own system Using tools to understand software without source Free and open source software Access to source code Free = freedom to use, modify, copy Some potential benefits Can build for different platforms and needs Development driven by community Different perspectives and ideas More people looking at the code for bugs/security issues Structure Volunteers, sponsored by companies Generally anyone can propose ideas and submit code Different structures in charge of what features/code gets in Free and open source software Tons of FOSS out there Nearly everything on myth Desktop applications (Firefox, Chromium, LibreOffice) Programming tools (compilers, libraries, IDEs) Servers (Apache web server, MySQL) Many companies contribute to FOSS Android core Apple Darwin Microsoft .NET A brief history of FOSS 1960s: Software distributed with hardware Source included, users could fix bugs 1970s: Start of software licensing 1974: Software is copyrightable 1975: First license for UNIX sold 1980s: Popularity of closed-source software Software valued independent of hardware Richard Stallman Started the free software movement (1983) The GNU project GNU = GNU's Not Unix An operating system with unix-like interface GNU General Public License Free software: users have access to source, can modify and redistribute Must share modifications under same -

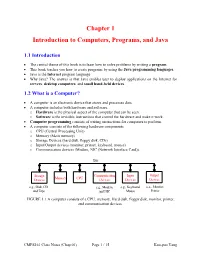

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

Some Preliminary Implications of WTO Source Code Proposala INTRODUCTION

Some preliminary implications of WTO source code proposala INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 HOW THIS IS TRIMS+ ....................................................................................................................................... 3 HOW THIS IS TRIPS+ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE TRANSFER OF SOURCE CODE .................................................................. 4 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ........................................................................................................................................... 4 AS A REMEDY FOR ANTICOMPETITIVE CONDUCT ............................................................................................................. 4 TAX LAW ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 IN GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ................................................................................................................................ 5 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE ACCESS TO SOURCE CODE ...................................................................... 5 COMPETITION LAW ................................................................................................................................................. -

Object-Oriented Programming Basics with Java

Object-Oriented Programming Object-Oriented Programming Basics With Java In his keynote address to the 11th World Computer Congress in 1989, renowned computer scientist Donald Knuth said that one of the most important lessons he had learned from his years of experience is that software is hard to write! Computer scientists have struggled for decades to design new languages and techniques for writing software. Unfortunately, experience has shown that writing large systems is virtually impossible. Small programs seem to be no problem, but scaling to large systems with large programming teams can result in $100M projects that never work and are thrown out. The only solution seems to lie in writing small software units that communicate via well-defined interfaces and protocols like computer chips. The units must be small enough that one developer can understand them entirely and, perhaps most importantly, the units must be protected from interference by other units so that programmers can code the units in isolation. The object-oriented paradigm fits these guidelines as designers represent complete concepts or real world entities as objects with approved interfaces for use by other objects. Like the outer membrane of a biological cell, the interface hides the internal implementation of the object, thus, isolating the code from interference by other objects. For many tasks, object-oriented programming has proven to be a very successful paradigm. Interestingly, the first object-oriented language (called Simula, which had even more features than C++) was designed in the 1960's, but object-oriented programming has only come into fashion in the 1990's. -

The Machine That Builds Itself: How the Strengths of Lisp Family

Khomtchouk et al. OPINION NOTE The Machine that Builds Itself: How the Strengths of Lisp Family Languages Facilitate Building Complex and Flexible Bioinformatic Models Bohdan B. Khomtchouk1*, Edmund Weitz2 and Claes Wahlestedt1 *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 1Center for Therapeutic Innovation and Department of We address the need for expanding the presence of the Lisp family of Psychiatry and Behavioral programming languages in bioinformatics and computational biology research. Sciences, University of Miami Languages of this family, like Common Lisp, Scheme, or Clojure, facilitate the Miller School of Medicine, 1120 NW 14th ST, Miami, FL, USA creation of powerful and flexible software models that are required for complex 33136 and rapidly evolving domains like biology. We will point out several important key Full list of author information is features that distinguish languages of the Lisp family from other programming available at the end of the article languages and we will explain how these features can aid researchers in becoming more productive and creating better code. We will also show how these features make these languages ideal tools for artificial intelligence and machine learning applications. We will specifically stress the advantages of domain-specific languages (DSL): languages which are specialized to a particular area and thus not only facilitate easier research problem formulation, but also aid in the establishment of standards and best programming practices as applied to the specific research field at hand. DSLs are particularly easy to build in Common Lisp, the most comprehensive Lisp dialect, which is commonly referred to as the “programmable programming language.” We are convinced that Lisp grants programmers unprecedented power to build increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence systems that may ultimately transform machine learning and AI research in bioinformatics and computational biology. -

Preview Fortran Tutorial (PDF Version)

Fortran i Fortran About the Tutorial Fortran was originally developed by a team at IBM in 1957 for scientific calculations. Later developments made it into a high level programming language. In this tutorial, we will learn the basic concepts of Fortran and its programming code. Audience This tutorial is designed for the readers who wish to learn the basics of Fortran. Prerequisites This tutorial is designed for beginners. A general awareness of computer programming languages is the only prerequisite to make the most of this tutorial. Copyright & Disclaimer Copyright 2017 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. If you discover any errors on our website or in this tutorial, please notify us at [email protected] i Fortran Table of Contents About the Tutorial ····································································································································i Audience ··················································································································································i -

Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK

1 From Start-ups to Scale-ups: Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK Abstract—This paper1 describes some of the challenges and research questions that target the most productive intersection opportunities when deploying static and dynamic analysis at we have yet witnessed: that between exciting, intellectually scale, drawing on the authors’ experience with the Infer and challenging science, and real-world deployment impact. Sapienz Technologies at Facebook, each of which started life as a research-led start-up that was subsequently deployed at scale, Many industrialists have perhaps tended to regard it unlikely impacting billions of people worldwide. that much academic work will prove relevant to their most The paper identifies open problems that have yet to receive pressing industrial concerns. On the other hand, it is not significant attention from the scientific community, yet which uncommon for academic and scientific researchers to believe have potential for profound real world impact, formulating these that most of the problems faced by industrialists are either as research questions that, we believe, are ripe for exploration and that would make excellent topics for research projects. boring, tedious or scientifically uninteresting. This sociological phenomenon has led to a great deal of miscommunication between the academic and industrial sectors. I. INTRODUCTION We hope that we can make a small contribution by focusing on the intersection of challenging and interesting scientific How do we transition research on static and dynamic problems with pressing industrial deployment needs. Our aim analysis techniques from the testing and verification research is to move the debate beyond relatively unhelpful observations communities to industrial practice? Many have asked this we have typically encountered in, for example, conference question, and others related to it. -

Php Tutorial

PHP About the Tutorial The PHP Hypertext Preprocessor (PHP) is a programming language that allows web developers to create dynamic content that interacts with databases. PHP is basically used for developing web-based software applications. This tutorial will help you understand the basics of PHP and how to put it in practice. Audience This tutorial has been designed to meet the requirements of all those readers who are keen to learn the basics of PHP. Prerequisites Before proceeding with this tutorial, you should have a basic understanding of computer programming, Internet, Database, and MySQL. Copyright & Disclaimer © Copyright 2016 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. If you discover any errors on our website or in this tutorial, please notify us at [email protected] i PHP Table of Contents About the Tutorial ........................................................................................................................................... -

Teach Yourself Perl 5 in 21 Days

Teach Yourself Perl 5 in 21 days David Till Table of Contents: Introduction ● Who Should Read This Book? ● Special Features of This Book ● Programming Examples ● End-of-Day Q& A and Workshop ● Conventions Used in This Book ● What You'll Learn in 21 Days Week 1 Week at a Glance ● Where You're Going Day 1 Getting Started ● What Is Perl? ● How Do I Find Perl? ❍ Where Do I Get Perl? ❍ Other Places to Get Perl ● A Sample Perl Program ● Running a Perl Program ❍ If Something Goes Wrong ● The First Line of Your Perl Program: How Comments Work ❍ Comments ● Line 2: Statements, Tokens, and <STDIN> ❍ Statements and Tokens ❍ Tokens and White Space ❍ What the Tokens Do: Reading from Standard Input ● Line 3: Writing to Standard Output ❍ Function Invocations and Arguments ● Error Messages ● Interpretive Languages Versus Compiled Languages ● Summary ● Q&A ● Workshop ❍ Quiz ❍ Exercises Day 2 Basic Operators and Control Flow ● Storing in Scalar Variables Assignment ❍ The Definition of a Scalar Variable ❍ Scalar Variable Syntax ❍ Assigning a Value to a Scalar Variable ● Performing Arithmetic ❍ Example of Miles-to-Kilometers Conversion ❍ The chop Library Function ● Expressions ❍ Assignments and Expressions ● Other Perl Operators ● Introduction to Conditional Statements ● The if Statement ❍ The Conditional Expression ❍ The Statement Block ❍ Testing for Equality Using == ❍ Other Comparison Operators ● Two-Way Branching Using if and else ● Multi-Way Branching Using elsif ● Writing Loops Using the while Statement ● Nesting Conditional Statements ● Looping Using -

CSC 272 - Software II: Principles of Programming Languages

CSC 272 - Software II: Principles of Programming Languages Lecture 1 - An Introduction What is a Programming Language? • A programming language is a notational system for describing computation in machine-readable and human-readable form. • Most of these forms are high-level languages , which is the subject of the course. • Assembly languages and other languages that are designed to more closely resemble the computer’s instruction set than anything that is human- readable are low-level languages . Why Study Programming Languages? • In 1969, Sammet listed 120 programming languages in common use – now there are many more! • Most programmers never use more than a few. – Some limit their career’s to just one or two. • The gain is in learning about their underlying design concepts and how this affects their implementation. The Six Primary Reasons • Increased ability to express ideas • Improved background for choosing appropriate languages • Increased ability to learn new languages • Better understanding of significance of implementation • Better use of languages that are already known • Overall advancement of computing Reason #1 - Increased ability to express ideas • The depth at which people can think is heavily influenced by the expressive power of their language. • It is difficult for people to conceptualize structures that they cannot describe, verbally or in writing. Expressing Ideas as Algorithms • This includes a programmer’s to develop effective algorithms • Many languages provide features that can waste computer time or lead programmers to logic errors if used improperly – E. g., recursion in Pascal, C, etc. – E. g., GoTos in FORTRAN, etc. Reason #2 - Improved background for choosing appropriate languages • Many professional programmers have a limited formal education in computer science, limited to a small number of programming languages.