The Vignette in 21St-Century American Fiction a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

Genres of Experience: Three Articles on Literacy Narratives and Academic Research Writing

GENRES OF EXPERIENCE: THREE ARTICLES ON LITERACY NARRATIVES AND ACADEMIC RESEARCH WRITING By Ann M. Lawrence A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Rhetoric and Writing – Doctor Of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT GENRES OF EXPERIENCE: THREE ARTICLES ON LITERACY NARRATIVES AND ACADEMIC RESEARCH WRITING By Ann M. Lawrence This dissertation collects three articles that emerged from my work as a teacher and a researcher. In Chapter One, I share curricular resources that I designed as a teacher of research literacies to encourage qualitative research writers in (English) education to engage creatively and critically with the aesthetics of their research-writing processes and to narrate their experiences in dialogues with others. Specifically, I present three heuristics for writing and revising qualitative research articles in (English) education: “PAGE” (Purpose, Audience, Genre, Engagement), “Problem Posing, Problem Addressing, Problem Posing,” and “The Three INs” (INtroduction, INsertion, INterpretation). In explaining these heuristics, I describe the rhetorical functions and conventional structure of all of the major sections of qualitative research articles, and show how the problem for study brings the rhetorical “jobs” of each section into purposive relationship with those of the other sections. Together, the three curricular resources that I offer in this chapter prompt writers to connect general rhetorical concerns with specific writing moves and to approach qualitative research writing as a strategic art. Chapters Two and Three emerged from research inspired by my teaching, during which writers shared with me personal literacy narratives, or autobiographical accounts related to their experiences with academic research writing. -

W41 PPB-Web.Pdf

The thrilling adventures of... 41 Pocket Program Book May 26-29, 2017 Concourse Hotel Madison Wisconsin #WC41 facebook.com/wisconwiscon.net @wisconsf3 Name/Room No: If you find a named pocket program book, please return it to the registration desk! New! Schedule & Hours Pamphlet—a smaller, condensed version of this Pocket Program Book. Large Print copies of this book are available at the Registration Desk. TheWisSched app is available on Android and iOS. What works for you? What doesn't? Take the post-con survey at wiscon.net/survey to let us know! Contents EVENTS Welcome to WisCon 41! ...........................................1 Art Show/Tiptree Auction Display .........................4 Tiptree Auction ..........................................................6 Dessert Salon ..............................................................7 SPACES Is This Your First WisCon?.......................................8 Workshop Sessions ....................................................8 Childcare .................................................................. 10 Children's and Teens' Programming ..................... 11 Children's Schedule ................................................ 11 Teens' Schedule ....................................................... 12 INFO Con Suite ................................................................. 12 Dealers’ Room .......................................................... 14 Gaming ..................................................................... 15 Quiet Rooms .......................................................... -

Anecdotes and Mimesis in Visual Music

Diego Garro The poetry of things: anecdotes and mimesis in Visual Music ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The poetry of things: anecdotes and mimesis in Visual Music DIEGO GARRO Keele University, School of Humanities – Music and Music Technology, The Clockhouse, Keele ST5 5BG, UK E-mail: [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION Ten years into the third millennium, Visual Music is a discipline firmly rooted in the vast array of digital arts, more diversified than ever in myriads of creative streams, diverging, intersecting, existing in parallel artistic universes, often contiguous, unaware of each other, perhaps, yet under the common denominator of more and more sophisticated media technology. Computers and dedicated software applications, allow us to create, by means of sound and animation synthesis, audio-visuals entirely in the digital domain. In line with the spectro-morphological tradition of much of the electroacoustic repertoire, Visual Music works produced by artists of sonic arts provenance, are predominantly abstract, especially in terms of the imagery they resort to. Nonetheless, despite the ensuing non-representational idiom that typifies many Visual Music works, composers enjoyed the riveting opportunity to employ material, both audio and video, which possess clear mimetic potential (Emmerson 1986, p.17), intended here as the ability to imitate nature or refer to it, more or less faithfully and literally. Composers working in the electronic media still enjoy the process of ‘capturing’ events from the real world and use them, with various strategies, as building blocks for time-based compositions. Therefore, before making their way into the darkness of computer-based studios, they still use microphones and video-cameras to harvest sounds, images, ideas, fragments, anecdotes to be thrown into the prolific cauldron of a compositional kitchen-laboratory-studio. -

Cypriot English Literature: a Stranger at the Feast Locally and Globally

Kunapipi Volume 33 Issue 1 Article 9 2011 Cypriot english literature: A stranger at the feast locally and globally Marios Vasiliou Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Vasiliou, Marios, Cypriot english literature: A stranger at the feast locally and globally, Kunapipi, 33(1), 2011. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol33/iss1/9 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Cypriot english literature: A stranger at the feast locally and globally Abstract My focus in this essay revolves around a corpus of literature written by Cypriots in English that has yet to define itself either as a hyphened branch of a national literature or as a minor independent category. So from the outset, my paper has a twofold task: firstly, to draw attention to the paradoxical position of Cypriot English writers who remain outside the literary feast both at home and abroad; and secondly, to explore the literary vicissitudes of some works of this corpus, and to examine how their minor position locally in relation to the dominant literatures in Greek and Turkish, and internationally in relation to global English — a position that Deleuze and Guattari (1986) describe as ‘minor literature’— has engendered syncretic aesthetics. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol33/iss1/9 83 MARIoS VASILIou cypriot English Literature: A Stranger at the Feast Locally and Globally My focus in this essay revolves around a corpus of literature written by Cypriots in English that has yet to define itself either as a hyphened branch of a national literature or as a minor independent category. -

Uncovering and Recovering the Popular Romance Novel A

Uncovering and Recovering the Popular Romance Novel A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jayashree Kamble IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Timothy Brennan December 2008 © Jayashree Sambhaji Kamble, December 2008 Acknowledgements I thank the members of my dissertation committee, particularly my adviser, Dr. Tim Brennan. Your faith and guidance have been invaluable gifts, your work an inspiration. My thanks also go to other members of the faculty and staff in the English Department at the University of Minnesota, who have helped me negotiate the path to this moment. My graduate career has been supported by fellowships and grants from the University of Minnesota’s Graduate School, the University of Minnesota’s Department of English, the University of Minnesota’s Graduate and Professional Student Assembly, and the Romance Writers of America, and I convey my thanks to all of them. Most of all, I would like to express my gratitude to my long-suffering family and friends, who have been patient, generous, understanding, and supportive. Sunil, Teresa, Kristin, Madhurima, Kris, Katie, Kirsten, Anne, and the many others who have encouraged me— I consider myself very lucky to have your affection. Shukriya. Merci. Dhanyavad. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Shashikala Kamble and Sambhaji Kamble. ii Abstract Popular romance novels are a twentieth- and twenty-first century literary form defined by a material association with pulp publishing, a conceptual one with courtship narrative, and a brand association with particular author-publisher combinations. -

A Call for Storytelling in Family Medicine Education William Ventres, MD, MA; Paul Gross, MD

SPECIAL ARTICLE Getting Started: A Call for Storytelling in Family Medicine Education William Ventres, MD, MA; Paul Gross, MD BACKGROUND: In this article we introduce family medicine edu- conclude by presenting the basic cators to storytelling as an important teaching tool. We describe components of effective stories and how stories are a critical part of the work of family physicians. We describing how to integrate the prac- review the rationales for family medicine educators to become tice of storytelling into family medi- skilled storytellers. We present the components of effective sto- cine education. ries, proposing two different perspectives on how to imagine, con- struct, and present them. We provide a list of resources for getting Background and Rationale started in storytelling and offer two personal vignettes that ar- Stories, Clinical Practice, and ticulate the importance of storytelling in the authors’ respective professional developments. We point the way forward for family Professional Development medicine educators interested in integrating storytelling into their The practice of family medicine (and, repertoire of teaching skills. in fact, all the generalist medical dis- ciplines) is integrally involved with (Fam Med 2016;48(9):682-7.) the telling of stories.1 Numerous practitioners and scholars from psy- chology, narrative studies, the medi- tories make differences in our medicine. It also reminds us just cal humanities, medical ethics, and care of patients. They help us how challenging it is for family med- medical education have discussed Sthink about our patients and icine educators to teach the skills of the crucial role that the telling, in- their family members. -

A Vignette Model for Distributed Teaching and Learning

A vignette model for distributed teaching and learning Marcel Chaloupka and Tony Koppi Centre forTeaching and Learning, University of Sydney Computer software and telecommunication technologies are being assimilated into the education sector. At a slower pace, educational methodologies have been evolving and gradually adopted by educators. The widespread and rapid assimilation of technology may be outstripping the uptake of better pedagogical strategies. Non-pedagogical development of content could lead to the development of legacy systems that constrain future developments. Problems have arisen with computer-based learning (CBL) materials, such as the lack of uptake of monolithic programmes that cannot be easily changed to keep pace with natural progress or the different requirements of different teachers and institutions. Also, hypertext/hypermedia learning environments have limitations in that following predefined paths is no more interactive thanpage turning. These considerations require a flexible and dynamic approach for the benefit of both the teacher and student. Courses may be constructed from vignettes to meet a desired purpose and to avoid the problems of adoption for the reasons that programmes cannot easily be changed or are not designed to meet particular needs. Vignettes are small, first-principle, first-person, heuristic activities (which are mimetic) from which courses can be constructed Vignettes use an object- orientated approach to the development of computer-based learning materials. Vignettes are objects that can be manipulated via a property sheet, which enables changing the object's inherent character or behaviour. A vignette object can interact with other vignette objects to create more complex educational interactions or models. The vignette approach leads to a development concept that is horizontally distributed across disciplines rather than vertically limited to single subjects. -

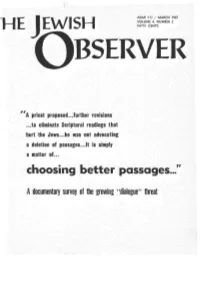

Choosing Better Passages:~."· ?

F' -~ . .. ·· . ( . · .-· · .. .•. ; .· .· , - . ; ·· · . .. .·· ...... ... ··" . .. .. ..· _.. ... - •· .-.· ... ..··· ;· ..· . : .··. ... · . .. ,. .. -· ....H .· , 'E --·_.:··.: . :E.. .·· w·· ··:·_· ._:·:"·1· ·s ··-.H. ·· .._._. · · :_-.·:-. _. ·. ". -. : .: ~~~J~''/ :U~~~~ - ~967 -·::-:.:< ·· · ~- . ·, .. -' .. · FIFTY CENTS · . · · ·- . .. .· . .. ·•· . ... .· .. .. ..· .·.·· .. , .. .. -. .. .·· .· .. ... .- . .. ' . .... ·' . , · . .. - . .. .. .. .. ·" - . -- . .•· . , - . ,, . - ·.... -. - . - .. · · -_-: :. ·.· ">- - -.··.--. : ·" A priest proposed·..• further revisions . : .· · . · · .> . ·~- :: -._ _..··· .-. -->. .. : . · . .. ..· ...- · .· .. · :": .. ~to eliminate Scriptural readings that · _. _ . ...: . ~- . ·: :· . · - . .. hurt the Jews ... he was not advocating . -· .. -· .· .... .·· ..· . .· ·· . " .. · . a deletion of passages.~ .It is simply : _ . _ . ... .. .· .-·· ·· .... -· ... a matter of ... choosing better passages:~." · ?: . ,. .: . -· - ·· ' . .. .· --.. Adocumentary survey of the growing "dialogue" threat -: .- ~ .- ... -·· -.~-~ ·· ~.- .··:.. ·. ... / . · - .. · ·- .· . .. .· _· .· ._ ... : .- ..... ..: . .. · - . ... .. ... · . .. .. .. · :: . - - . .· .. ' . ' - . ~ . ... .. -· .. .: . ·· _,. .. .. - ..· ..· ·· ,· . .. .. .... ~- . - - .. _,. : _.. _.· ·.. ...- .... ..'. .· .. -· -- .· . · ... .· .· · THE JEWISH QBSERVER In this issue ... "CHOOSING BETTER PASSAGES'' ..• A documentary survey of the growing "dialogue" threat. We believe that this survey should be read by thinking Jews far beyond the circle -

Imaginative, Immersive and Interactive Engagements

HANNA-RIIKKA ROINE HANNA-RIIKKA Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 2197 HANNA-RIIKKA ROINE Imaginative, Immersive and Interactive Engagements Imaginative, Immersive and Interactive Engagements The rhetoric of worldbuilding in contemporary speculative fiction AUT 2197 AUT HANNA-RIIKKA ROINE Imaginative, Immersive and Interactive Engagements The rhetoric of worldbuilding in contemporary speculative fiction ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Board of the School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the auditorium Pinni B 1097, Kanslerinrinne 1, Tampere, on 27 August 2016, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE HANNA-RIIKKA ROINE Imaginative, Immersive and Interactive Engagements The rhetoric of worldbuilding in contemporary speculative fiction Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 2197 Tampere University Press Tampere 2016 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Languages, Translation Studies and Literary Studies Finland The originality of this thesis has been checked using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service in accordance with the quality management system of the University of Tampere. Copyright ©2016 Tampere University Press and the author Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Distributor: [email protected] https://verkkokauppa.juvenes.fi Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 2197 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1696 ISBN 978-952-03-0194-1 (print) ISBN 978-952-03-0195-8 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://tampub.uta.fi Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print 441 729 Tampere 2016 Painotuote ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing a PhD dissertation is often likened to making a long journey. For me, however, it resembled putting together a puzzle. The biggest challenge was that, at the beginning, I had only a vague idea of what the puzzle would look like when completed. -

If:Book Futureofthebook.Org.Uk July 2008

read:write Digital Possibilities for Literature A report for Arts Council England by Mary Harrington & Chris Meade if:book futureofthebook.org.uk July 2008 Report commissioned by Arts Council England Contents 1. Executive summary 6 1.1 Brief and Methodology 6 1.2 Introduction 6 1.3 Web culture 6 1.4 New Writing and the Web 7 1.5 Born digital creative forms 7 1.6 Reading & writing 7 1.7 Live literature 8 1.8 Publishing 8 1.9 Technology 8 1.10 Conclusion 9 2. Introduction 10 2.1 Familiar objections 11 2.2 Rapid change 11 3. Web Culture 12 3.1 Introduction 12 3.2 Key ideas for the literature sector 12 3.2.1 The read/write Web 3.2.2 Community building strategies 3.2.3 Cultural loss leaders 3.2.4 Convergence and curation 3.2.5 Opportunities for literature 3.3. A short history of the network 13 3.3.1 The network 3.3.2 The World Wide Web 3.3.3 The first bubble 3.3.4 Web 2.0 after the dot-com bust 3.3.5 Impacts of Web 2.0 3.3.6 Ideas: the read/write Web 3.3.7 Where next? 4. New writing and the web 17 4.1 Literary magazines online 17 4.1.1 Overview 4.1.2 A first filter of quality 4.1.3 Technology 4.1.4 Print magazines online 4.1.5. Case study: Pen Pusher 4.1.5.i 21st-century literary endeavour 4.1.5.ii Using digital technologies to build community 4.1.5.iii Ad-supported 4.2 Online-only (ezines) 19 4.2.1 Case study: Pulp.net and 3:AM 4.3 Words are cheap 21 4.4 Writers’ Communities 21 4.4.1 Overview 4.4.2 Writing for publication 2 4.4.3 User case study: Joe Dunthorne 4.4.4 Case study: YouWriteOn.com 4.4.5 Writing for fun 5. -

Internet and Freedom of Expression

EUROPEAN MASTER DEGREE IN HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATISATION 2000-2001 RAOUL WALLENBERG INSTITUTE Internet and Freedom of expression Rikke Frank Jørgensen© [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. Gregor Noll Abstract Internet challenges the right to freedom of expression. On the one hand, Internet empowers freedom of expression by providing individuals with new means of expressions. On the other hand, the free flow of information has raised the call for content regulation, not least to restrict minors’ access to potentially harmful information. This schism has led to legal attempts to regulate content and to new self- regulatory schemes implemented by private parties. The attempts to regulate content raise the question of how to define Internet in terms of “public sphere” and accordingly protect online rights of expression. The dissertation will argue that Internet has strong public sphere elements, and should receive the same level of protection, which has been given to rights of expression in the physical world. Regarding the tendency towards self- regulation, the dissertation will point to the problem of having private parties manage a public sphere, hence regulate according to commercial codes of consumer demand rather than the principles inherent in the rights of expressions, such as the right of every minority to voice her opinion. The dissertation will conclude, that the time has come for states to take on their responsibility and strengthen the protection of freedom of expression on Internet. 29.600 words 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. Point of departure .................................................................................................. 4 1.2. Aim of dissertation................................................................................................. 6 2. System, lifeworld and Internet.........................................................................................