Rosemary Lane and Rag Fair C. 1690-1765

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitchell Final4print.Pdf

VICTORIAN CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS Donald E. Hall, Series Editor VICTORIAN LESSONS IN EMPATHY AND DIFFERENCE Rebecca N. Mitchell THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Columbus Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mitchell, Rebecca N. (Rebecca Nicole), 1976– Victorian lessons in empathy and difference / Rebecca N. Mitchell. p. cm. — (Victorian critical interventions) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1162-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1162-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9261-7 (cd) 1. English literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Art, English—19th century. 3. Other (Philosophy) in literature. 4. Other (Philosophy) in art. 5. Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870— Criticism and interpretation. 6. Eliot, George, 1819–1880—Criticism and interpretation. 7. Hardy, Thomas, 1840–1928—Criticism and interpretation. 8. Whistler, James McNeill, 1834– 1903—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series: Victorian critical interventions. PR468.O76M58 2011 820.9’008—dc22 2011010005 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1162-5) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9261-7) Cover design by Janna Thompson Chordas Type set in Adobe Palatino Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materi- als. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS List of Illustrations • vii Preface • ix Acknowledgments • xiii Introduction Alterity and the Limits of Realism • 1 Chapter 1 Mysteries of Dickensian Literacies • 27 Chapter 2 Sawing Hard Stones: Reading Others in George Eliot’s Fiction • 49 Chapter 3 Thomas Hardy’s Narrative Control • 70 Chapter 4 Learning to See: Whister's Visual Averstions • 88 Conclusion Hidden Lives and Unvisited Tombs • 113 Notes • 117 Bibliography • 137 Index • 145 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 James McNeill Whistler, The Miser (1861). -

Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ______

Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ____________________________________________________________________________________ Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll The development of housing for the working- classes in Victorian Southwark Part 2: The buildings of Southwark Martin Stilwell © Martin Stilwell 2015 Page 1 of 46 Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ____________________________________________________________________________________ This paper is Part 2 of a dissertation by the author for a Master of Arts in Local History from Kingston University in 2005. It covers the actual philanthropic housing schemes before WW1. Part 1 covered Southwark, its history and demographics of the time. © Martin Stilwell 2015 Page 2 of 46 Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ____________________________________________________________________________________ © Martin Stilwell 2015 Page 3 of 46 Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ____________________________________________________________________________________ Cromwell Buildings, Red Cross Street 1864, Improved Industrial Dwellings Company (IIDC) 18 dwellings, 64 rooms1, 61 actual residents on 1901 census2 At first sight, it is a surprise that this relatively small building has survived in a predominantly commercial area. This survival is mainly due to it being a historically significant building as it is only the second block built by Sydney Waterlow’s IIDC, and the first of a new style developed by Waterlow in conjunction with builder -

Directory of London and Westminster, & Borough of Southwark. 1794

Page 1 of 9 Home Back Directory of London and Westminster, & Borough of Southwark. 1794 SOURCE: Kent's Directory for the Year 1794. Cities of London and Westminster, & Borough of Southwark. An alphabetical List of the Names and Places of Abode of the Directors of Companies, Persons in Public Business, Merchts., and other eminent Traders in the Cities of London and Westminster, and Borough of Southwark. Dabbs Tho. & John, Tanners, Tyre's gateway, Bermondsey st. Dacie & Hands, Attornies, 30, Mark lane Da Costa Mendes Hananel, Mercht. 2, Bury str. St. Mary-ax Da Costa & Jefferson, Spanish Leather dressers, Bandy leg walk, Southwark Da Costa J. M. sen. India Agent & Broker, 2, Bury street, St. Mary- ax, or Rainbow Coffee house Daintry, Ryle & Daintry, Silkmen, 19, Wood street Daker Joseph, Buckram stiffner, 14, Whitecross street Dakins & Allinson, Wholesale Feather dealers, 23, Budge row Dalby John, Fellmonger, Old Ford Dalby John, Goldsmith & Jeweller, 105, New Bond street Dalby Wm. Linen draper, 25, Duke street, Smithfield Dalby & Browne, Linen drapers, 158, Leadenhall street Dale E. Wholesale Hardware Warehouse, 49, Cannon street Dale George, Sail maker, 72, Wapping wall Dale J. Musical Instrument maker, 19, Cornhill, & 130, Oxford str. Dale John, Biscuit baker, 3, Shadwell dock Dalgas John, Broker, 73, Cannon street Dallas Robert, Insurance broker, 11, Mincing lane Dallisson Thomas, Soap maker, 149, Wapping Dalston Wm. Grocer & Brandy Mercht. 7, Haymarket Dalton James, Grocer & Tea dealer, Hackney Dalton & Barber, Linen drapers, 28, Cheapside Daly & Pickering, Ironmongers, &c. 155, Upper Thames str. Dalzell A. Wine, Spirit & Beer Mercht. 4, Gould sq. Crutched-f. Danby Michael, Ship & Insurance broker, Virginia Coffee house, Cornhill Dangerfield & Lum, Weavers, 17, Stewart street, Spitalfields Daniel Edward, Tea dealer, Southampton street, Strand Daniel & Co. -

Third Notice. Third Notice. Second Notice

Prisoners in N E W G A T E, for the County Ca.T.omili-slreir, in tht* City of London*, Corn-buy:;' ?.aj Agent. of Middlesex. James Newton, formerly ofthe Parish os St. Ann Blacksryarj, Second Notice. late of Warwick-court, in the Parisli of Christ-church, both in the City of London, Taylor. John Lea, formerly of Stoiirbridge, iri the County of Wor cester, late of Brick-lane, in the Parisli of St. Luke, in the County of Middlesex, Ironmonger and Nailer. Prisoners in the M A R S H A L S E A Prison» James Dyerj otherwise IVfuster, formerly of the New Square in the County of Surry. in the Minories, in the Parisli of St. Luke Aidgate, London, late of Twickenham and Chelsea in thc County of M.ddlesex, Second Notice. Mariner. Martha Cooper, arrested by the Name of Martha Mundav, Third Notice. formerly of the Town of Derby, late of the Parilh of St. John Cooke, late of Yarmouth, in the County of Norfolk, Paul Covent Garden, Spinster. Mariner. Mary Craven, formerly of Mary le Bon, late of Bloomsbury James Munford, late of Gray's Inn-lane, in the Parilh of St. Square, both in the County of Middlesex, Widow. Andrew Holborn, in the County of Middlesex, Bricklayer. Sarah Turner, formerly os the Pariih of St. Mary Lambeth, Adam Henley, formerly of Little Russel-street, in the Parilh of in the County of Surry, late of the Parisli of St. Andrew St. George Bloomsbury, late of Dean-street, in the Parisli Holbourn, in the County of Middlesex, Victualler. -

Crime on Public Transport March 2016

Police and Crime Committee Crime on public transport March 2016 ©Greater London Authority March 2016 Police and Crime Committee Members Joanne McCartney (Chair) Labour Jenny Jones (Deputy Chair) Green Caroline Pidgeon MBE (Deputy Chair) Liberal Democrat Tony Arbour Conservative Jennette Arnold OBE Labour Kemi Badenoch Conservative Andrew Dismore Labour Len Duvall Labour Roger Evans Conservative Role of the Police and Crime Committee The Police and Crime Committee examines the work of the Mayor's Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) and reviews the Police and Crime Plan for London. The Committee can also investigate anything that it considers to be of importance to policing and crime reduction in Greater London and make recommendations for improvements. Contact Janette Roker, Scrutiny Manager Email: [email protected] Contact: 020 7983 6562 For media enquiries: Mary Dolan, External Relations Email: [email protected] Contact: 020 7983 4603 2 Contents Chair’s foreword ................................................................................................. 4 Executive summary ............................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 8 2. Types of crime committed on public transport .......................................... 9 3. Tackling crime and anti-social behaviour on public transport ................. 13 4. Policing the 24 hour city .......................................................................... -

Living Wall Walking Tour 5 April

Living Wall Walking Tour 5 April Royal Quarter 3km Bridges East 4km 1 Bridges East 4km 2 Bridges East – Route Directions (4km) AAA 105A Minories, London EC3N 1LA, UK 134 m Head north on Minories/A1211 toward Goodman's Yard 77 m Sharp left onto Minories 57 m BBB Biotecture --- 52 Minories EC3N 1JA 207 m Head north on Minories toward Crosswall 3 m Turn left onto Crosswall 139 m Continue onto Crutched Friars 65 m 48 Crutched Friars, London EC3N 2AP, UK 702 m Head northeast on Crutched Friars toward Savage Gardens 31 m Turn right onto Savage Gardens 69 m CCC Frosts --- Doubletree by Hilton, 7 Pepys St EC3N 4AF Turn right onto Pepys St 10 m Turn left onto Savage Gardens 69 m Turn right onto Trinity Square 38 m Turn right onto Muscovy St 83 m Turn left onto Seething Ln 34 m Turn right onto Byward St/A100 58 m Slight right onto Great Tower St 192 m Continue onto Eastcheap 46 m Turn right onto Rood Ln 72 m 3 DDD Biotecture --- 20 Fenchurch Street EC3M 3BY 1.04 km Head south on Rood Ln toward Plantation Ln 72 m Turn right onto Eastcheap 244 m Turn left onto King William St/A3Continue to follow A3 595 m Turn right onto Green Dragon Ct 100 m Continue onto Middle Rd 33 m Middle Road, London SE1 1TU, UK 1.43 km Head east on Middle Rd toward Bedale St 33 m EEE Treebox --- Borough Market, Stoney Street SE1 9AA Turn left onto Cathedral St 113 m Turn right toward Clink St 25 m Turn left onto Clink St 162 m Turn right onto Bank End 38 m Bank End turns left and becomes Bankside 266 m Turn right onto New Globe Walk 6 m Turn left toward Millennium Bridge -

Policing the Bridges Appendix 1.Pdf

Appendix One NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Policing the Bridges and allocation of costs to the Bridge House Estates OPINION Introduction 1. This Opinion considers the nature and extent of the City's obligations as to the policing of the City's bridges and the extent to which those costs may be attributed to the Bridge House Estates. It focuses on general policing responsibilities rather than any specific project, although the issue has recently received renewed attention as the result of a project to install river cameras at the bridges. Issues concerning the quantum of any contribution and a Trustee‟s general duty to act in the best interests of Trust are not dealt with in this Opinion. 2. In order to provide context and to inform interpretation, some historical constitutional background is included. This has however been confined to material which assists in deciding the extent of the obligations and sources of funding rather than providing a broader narrative. After a short account of the history of the „Watch‟, each bridge is considered in turn, concluding, in each case, with an assessment of the position under current legislation. Establishment of Watches and the Bridges 3. In what appears to be a remarkably coordinated national move, the Statute of Winchester 1285 (13 Edw. I), commanded that watch be kept in all cities and towns and that two Constables be chosen in every "Hundred" or "Franchise"; specific to the City, the Statuta Civitatis London, also passed in 1285, regularised watch arrangements so that the gates of London would be shut every night and that the City‟s twenty-four Wards, would each have six watchmen controlled by an Alderman. -

Church Historical Writing in the English Transatlantic World During the Age of Enlightenment1

CSCH President’s Address 2012 Church Historical Writing in the English Transatlantic World during the Age of Enlightenment1 DARREN W. SCHMIDT The King’s University College My research stemming from doctoral studies is focused on English- speaking evangelical use, interpretation, and production of church history in the eighteenth century, during which religious revivals on both sides of the North Atlantic signalled new developments on many fronts. Church history was of vital importance for early evangelicals, in ways similar to earlier generations of Protestants beginning with the Reformation itself. In the eighteenth century nerves were still sensitive from the religious and political intrigues, polemic, and outright violence in the seventeenth- century British Isles and American colonies; terms such as “Puritan” and “enthusiast” maintained the baggage of suspicion. Presumed to be guilty by association, evangelical leaders were compelled to demonstrate that the perceived “surprising work of God” in their midst had a pedigree: they accordingly construed their experience as part of a long narrative of religious ebb and flow, declension and revival. Time and time again, eighteenth-century evangelicals turned to the pages of the past to vindicate and to validate their religious identity.2 Browsing through historiographical studies, one is hard-pressed to find discussion of eighteenth-century church historical writing. There is general scholarly agreement that the Protestant Reformation gave rise to a new historical interest. In answer to Catholic charges of novelty, Historical Papers 2012: Canadian Society of Church History 188 Church Historical Writing in the English Transatlantic World Protestants critiqued aspects of medieval Catholicism and sought to show their continuity with early Christianity. -

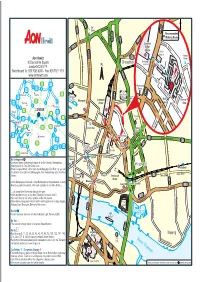

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

861 Sq Ft Headquarters Office Building Your Own Front Door

861 SQ FT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDING YOUR OWN FRONT DOOR This quite unique property forms part of the building known as Rotherwick House. The Curve comprises a self-contained building, part of which is Grade II Listed, which has been comprehensively refurbished to provide bright contemporary Grade A office space. The property — located immediately to the east of St Katharine’s Dock and adjoining Thomas More Square — benefits from the immediate area which boasts a wide variety of retail and restaurant facilities. SPECIFICATION • Self-contained building • Generous floor to ceiling heights • New fashionable refurbishment • Full-height windows • New air conditioning • Two entrances • Floor boxes • Grade II Listed building • LG7 lighting with indirect LED up-lighting • Fire and security system G R E A ET T THE TEA TRE E D S A BUILDING OL S T E R SHOREDITCH N S HOUSE OLD STREET T R E E T BOX PARK AD L RO NWEL SHOREDITCH CLERKE C I HIGH STREET T Y R G O O A S D W S F H A O E R L U A L R T AD T H I O R T R N A S STEPNEY D’ O O M AL G B N A GREEN P O D E D T H G O T O WHITECHAPEL A N N R R R O D BARBICAN W O CHANCERY E A FARRINGDON T N O LANE D T T E N H A E M C T N O C LBOR A D O HO M A IGH MOORGATE G B O H S R R U TOTTENHAM M L R LIVERPOOL P IC PE T LO E COURT ROAD NDON WA O K A LL R N R H STREET H C L C E E O S A I SPITALFIELDS I IT A A W B N H D L E W STE S R PNEY WAY T O J R U SALESFORCE A E HOLBORN B T D REE TOWER E ST N I D L XFOR E G T O W R E K G ES H ALDGATE I A H E N TE A O M LONDON MET. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture.