SUBDIVISION and INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT in HASTINGS DISTRICT Best Practice Design Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Drinking Water the Safety of Kawerau’S Drinking Water Is a Top Priority for Council

OUR DRINKING WATER THE SAFETY OF KAWERAU’S DRINKING WATER IS A TOP PRIORITY FOR COUNCIL GOVERNMENT INQUIRY INTO DRINKING WATER Following the 2016 Havelock North water contamination which made more than 5000 people ill and caused numerous businesses to close for days, a government inquiry was held. The Stage Two Report from the Inquiry has recommended significant changes to New Zealand’s drinking water standards and the treatment of drinking water nationally. RESIDUAL TWO OF THE KEY TREATMENT DISINFECTION RECOMMENDATIONS of all drinking of drinking water OF THE REPORT water supplies i.e. treatment with chlorine WHAT IT MEANS FOR KAWERAU Council has made the decision that the only way to ensure the safety of our drinking water is to begin chlorination. From 1 July 2018, chlorine will be added to the water supply. WHY DO WE NEED TO START USING CHLORINE? Treating water with chlorine is backed up by science and more than a century of use around the world as a safe and effective water disinfectant. • Chlorine is recognised world-wide as the most effective way to kill bacteria, such as campylobacter, in drinking water supplies. • UV treatment does effectively clean water but only at the point of treatment. • Chlorine stays in the water so that if bugs get in at some point in the pipe network, e.g. through a mains break or contamination from a back flow, the chlorine will kill them. For more information visit kaweraudc.govt.nz or call 07 306 9009 SOME USEFUL FACTS ON CHLORINE DOES CHLORINE AFFECT THE TASTE WHY IS CHLORINE NEEDED AS WELL AND SMELL OF DRINKING WATER? AS UV TREATMENT? Not usually. -

Kids Voting Registered Schools

Name of School Address City or district General council area Electorate Cromwell College Barry Ave, Cromwell Central Otago Waitaki 9310 District Council Aidanfield Christian Nash Road, Oaklands, Christchurch City Wigram School 8025 Council Heaton Normal Heaton Street, Merivale, Christchurch City Ilam Intermediate Christchurch 8052 Council Queen's High School Surrey Street, St Clair, Dunedin City Dunedin South Dunedin 9012 Council Columba College Highgate, Kaikorai, Dunedin City Dunedin North Dunedin 9010 Council Longford Intermediate Wayland Street, Gore Gore District Clutha-Southland 9710 Council Sacred Heart Girls' Clyde Street, Hamilton Hamilton City Hamilton East College East, Hamilton 3216 Council Hamilton Girls' High Ward Street, Hamilton Hamilton City Hamilton West School 3204 Council Peachgrove Peachgrove Road, Hamilton City Hamilton East Intermediate Hamilton 3216 Council Karamu High School Windsor Ave, Hastings, Hastings District Tukituki 4122 Council Hastings Christian Copeland Road, Hawkes Hastings District Tukituki School Bay 4122 Council Taita College Eastern Hutt Road, Hutt City Council Rimutaka Holborn 5019 Avalon Intermediate High Street, Avalon, Hutt City Council Rimutaka School Lower Hutt 5011 St Oran's College High Street, Boulcott, Hutt City Council Hutt South Lower Hutt 5010 Naenae Intermediate Walters Street, Avalon, Hutt City Council Rimutaka Lower Hutt 5011 Sacred Heart College Laings Road, Lower hutt Hutt City Council Rimutaka 5010 Southland Boys' High Herbert Street, Invercargiill City Invercargill School Invercargill -

Hawke's Bay Population Tends to Be Older Than the National Average

HAWKE’S BAY – PEOPLE, PLACE, PROSPERITY. THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF LAND USE CHANGE IN HAWKE’S BAY. KELLOGG RURAL LEADERSHIP PROGRAMME COURSE 41 2020 CLARE EASTON 1 I wish to thank the Kellogg Programme Investing Partners for their continued support: Disclaimer In submitting this report, the Kellogg Scholar has agreed to the publication of this material in its submitted form. This report is a product of the learning journey taken by participants during the Kellogg Rural Leadership Programme, with the purpose of incorporating and developing tools and skills around research, critical analysis, network generation, synthesis and applying recommendations to a topic of their choice. The report also provides the background for a presentation made to colleagues and industry on the topic in the final phase of the Programme. Scholars are encouraged to present their report findings in a style and structure that ensures accessibility and uptake by their target audience. It is not intended as a formal academic report as only some scholars have had the required background and learning to meet this standard. This publication has been produced by the scholar in good faith on the basis of information available at the date of publication, without any independent verification. On occasions, data, information, and sources may be hidden or protected to ensure confidentially and that individuals and organisations cannot be identified. Readers are responsible for assessing the relevance and accuracy of the content of this publication & the Programme or the scholar cannot be liable for any costs incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying solely on the information in this publication. -

Please See Attached Party List Dear Parties ENV-2020-AKL-000005 Te

ENVIRONMENT COURT OF NEW ZEALAND In reply, please quote reference 23 March 2020 ENV-2020-314-000001 By email: Please see attached party list Dear Parties ENV-2020-AKL-000005 Te Mata Mushroom Company Limited v Hastings District Council & Hawke's Bay Regional Council ENV-2020-AKL-000007 CDL Land New Zealand Limited v Hawke's Bay Regional Council Topic: Appeal against a decision relating to an application for consents for existing facilities at Brookvale Road, Havelock North (discharge contaminants into air, land use consents) I refer to the joint memorandum of counsel for the respondents dated 20 March 2020. The presiding Judge, having read and considered the correspondence, has directed as follows: In light of the rapidly changing situation with COVID-19, it is unlikely that the Court will have any mediators available over the next four weeks. Accordingly, the parties may wish to continue discussions between themselves. A mediation date will be allocated for mid-May 2020, subject to further review. Kind regards Alice McIntosh Hearing Manager Direct Dial: 09 302 8307 email: [email protected] Environment Court of New Zealand Specialist Courts and Tribunals Centre | Level 2 | 41 Federal Street | DX CX 10086 | PO Box 7147 | Wellesley Street | Auckland 1010 Telephone: 09 9169091 | Fax: 09 9169090 LIST OF PARTIES Lodgement: ENV-2020-AKL-000005 Te Mata Mushroom Company Limited v Hastings District Council & Hawke's Bay Regional Council Initiator Te Mata Mushroom Lara Blomfield, Sainsbury Logan & Williams, PO Box 41 / Company Limited -

Notes Subscription Agreement)

Amendment and Restatement Deed (Notes Subscription Agreement) PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited Issuer The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 Subscribers 3815658 v5 DEED dated 2020 PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited ("Issuer") The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 ("Subscribers" and each a "Subscriber") INTRODUCTION The parties wish to amend and restate the Notes Subscription Agreement as set out in this deed. COVENANTS 1. INTERPRETATION 1.1 Definitions: In this deed: "Notes Subscription Agreement" means the notes subscription agreement dated 7 December 2011 (as amended and restated on 4 June 2015) between the Issuer and the Subscribers. "Effective Date" means the date notified by the Issuer as the Effective Date in accordance with clause 2.1. 1.2 Notes Subscription Agreement definitions: Words and expressions defined in the Notes Subscription Agreement (as amended by this deed) have, except to the extent the context requires otherwise, the same meaning in this deed. 1.3 Miscellaneous: (a) Headings are inserted for convenience only and do not affect interpretation of this deed. (b) References to a person include that person's successors, permitted assigns, executors and administrators (as applicable). (c) Unless the context otherwise requires, the singular includes the plural and vice versa and words denoting individuals include other persons and vice versa. (d) A reference to any legislation includes any statutory regulations, rules, orders or instruments made or issued pursuant to that legislation and any amendment to, re- enactment of, or replacement of, that legislation. (e) A reference to any document includes reference to that document as amended, modified, novated, supplemented, varied or replaced from time to time. -

Local Government Investment in Business and Industry Support

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! REVIEW!OF!LOCAL! ! GOVERNMENT!INVESTMENT!IN!! BUSINESS!AND!INDUSTRY! SUPPORT!ACROSS!THE!HAWKE’S! BAY!REGION! ! ! !! !Final!Report!for!Hawke’s!Bay!Councils! !December!2020! ! ! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! TABLE!OF!CONTENTS! LIST!OF!FIGURES!............................................................................................!5! 1.0! EXECUTIVE!SUMMARY!.............................................................................!6! 1.1! Economic!development!activities!and!services!currently!being!provided!..........................!6! 1.2! Current!investment!in!activities!and!services!...................................................................!8! 1.3! Assessment!of!rationale!and!fit!of!activities!and!services!being!delivered!........................!9! 1.4! Effectiveness!and!efficiency!...........................................................................................!11! 1.5! Survey!of!key!stakeholders!............................................................................................!15! 1.6! Case!for!Change!.............................................................................................................!17! 2.0! RECOMMENDATIONS!............................................................................!19! 3.0! INTRODUCTION!.....................................................................................!23! 4.0! PURPOSE!OF!REVIEW!.............................................................................!24! 5.0! SCOPE!OF!REVIEW!.................................................................................!25! -

Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop

Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop Eric B. Spurr Landcare Research C. John Ralph US Forest Service Landcare Research Science Series No. 32 Development of Bird Population Monitoring in New Zealand: Proceedings of a Workshop Eric B. Spurr Landcare Research C. John Ralph US Forest Service (Compilers) Landcare Research Science Series No. 32 Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2006 © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2006 This information may be copied or reproduced electronically and distributed to others without limitation, provided Landcare Research New Zealand Limited is acknowledged as the source of information. Under no circumstances may a charge be made for this information without the express permission of Landcare Research New Zealand Limited. CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Spurr, E.B. Development of bird population monitoring in New Zealand: proceedings of a workshop / Eric B. Spurr and C. John Ralph, compilers – Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, 2006. (Landcare Research Science series, ISSN 1172-269X; no. 32) ISBN-13: 978-0-478-09384-1 ISBN-10: 0-478-09384-5 1. Bird populations – New Zealand. 2. Birds – Monitoring – New Zealand. 3. Birds – Counting – New Zealand. I. Spurr, E.B. II. Series. UDC 598.2(931):574.3.087.001.42 Edited by Christine Bezar Layout design Typesetting by Wendy Weller Cover design by Anouk Wanrooy Published by Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, PO Box 40, Lincoln 7640, New Zealand. 3 Contents Summary ..............................................................................................................................4 -

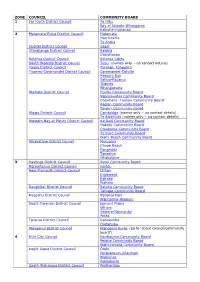

CB List by Zone and Council

ZONE COUNCIL COMMUNITY BOARD 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Matamata-Piako District Council Matamata Morrinsville Te Aroha Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau (names only – no contact details) Taupo District Council Turangi- Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamata Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero -Tuakau Community Board Raglan Community Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge (names only – no contact details) Te Awamutu (names only – no contact details) Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitikei District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural (go to ‘about council/community board’) 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board -

2019 Women Council Members.Xlsx

Total number of Women Council Total Council % Women Council Women council Council Members % Women Council Authority Members 2016 members 2016 Members 2016 members 2019 2019 Members 2019 Tararua District Council 4 9 44% 7 9 78% Wellington City Council 5 15 33% 11 15 73% Wairoa District Council 2 7 29% 4 7 57% Napier City Council 6 13 46% 7 13 54% Nelson City Council 3 13 23% 7 13 54% Hastings District Council 6 15 40% 8 15 53% Canterbury Regional Council 3 7 43% 7 14 50% Gisborne District Council 4 14 29% 7 14 50% Otago Regional Council 3 12 25% 6 12 50% South Wairarapa District Council 5 10 50% 5 10 50% Tasman District Council 3 14 21% 7 14 50% Waikato District Council 8 14 57% 7 14 50% Clutha District Council 7 15 47% 7 15 47% Hamilton City Council 3 13 23% 6 13 46% Hutt City Council 6 12 50% 6 13 46% Wellington Regional Council 6 13 46% 6 13 46% Buller District Council 4 11 36% 5 11 45% Hurunui District Council 4 10 40% 5 11 45% Kāpiti Coast District Council 3 11 27% 5 11 45% Rotorua District Council 4 11 36% 5 11 45% Waimakariri District Council 2 11 18% 5 11 45% Whakatane District Council 3 11 27% 5 11 45% Chatham Islands Council 3 9 33% 4 9 44% Kaipara District Council 5 9 56% 4 9 44% Kawerau District Council 4 9 44% 4 9 44% Waimate District Council 4 9 44% 4 9 44% Palmerston North District Council 7 16 44% 7 16 44% Auckland Council 8 21 38% 9 21 43% Central Otago District Council 3 11 27% 5 12 42% Rangitīkei District Council 5 12 42% 5 12 42% Taupō District Council 5 11 45% 5 12 42% Ashburton District Council 5 13 38% 4 10 40% Far -

Monthy Grant Summary April 2019-Feb 2020 .Xlsx

Organisation Name TLA Amount Requested Allocated Amount WAIKATO / BOP Prostate Cancer Foundation of N Z Inc Hamilton City Council $64,434.54 $35,000.00 K'aute Pasifika Trust Hamilton City Council $25,690.00 $10,000.00 Swim Waikato Inc Hamilton City Council $56,000.00 $45,000.00 Matamata Clay Target Club Inc Matamata-Piako District Council $8,849.00 $7,703.00 Highlands Amateur Swimming Club Inc New Plymouth District Council $10,000.00 $3,333.00 T F K A - Pukekura Free Kindergarten New Plymouth District Council $3,600.00 $3,600.00 Fitzroy Surf Club Inc New Plymouth District Council $8,945.00 $5,000.00 Opotiki Primary School Opotiki District Council $20,580.00 $20,580.00 Photoplayer Restoration Trust Opotiki District Council $28,200.00 $10,000.00 B o P Indoor Bowls Centre Inc Rotorua District Council $5,579.00 $5,579.00 Thames Rugby & Sports Club Inc Thames-Coromandel District Council $31,620.00 $20,000.00 Thames Valley Tangata Ora Trust Thames-Coromandel District Council $4,768.00 $4,311.00 Whangamata Community Services Trust Thames-Coromandel District Council $1,285.00 $1,048.00 Tauranga Primary School Tauranga City Council $10,000.00 $7,000.00 Bay of Plenty Dragon Boat Club Inc Tauranga City Council $18,689.00 $5,000.00 Tauranga Living Without Violence Collective Trust Tauranga City Council $40,000.00 $20,000.00 Otumoetai Tennis Club Inc Tauranga City Council $26,211.00 $10,000.00 W B O P P A - Pyes Pa Playcentre Tauranga City Council $9,685.30 $6,000.00 Oropi School Tauranga City Council $23,990.00 $10,000.00 Kidz Need Dadz Charitable -

2020 LDEG COMMITTEE Land Development Engineering Group

Ensuring Quality LDEG Infrastructure 2020 LDEG COMMITTEE Land Development Engineering Group Wellington-Taranaki Representative & Chair Tony McGlynn —(Developments Team Leader, Palmerston North City Council) Tony arrived in New Zealand (from Letterkenny, Co Donegal Ireland) in 1984. He started working with general contractors E.Carson & Sons Ltd (Upper Hutt). After 10 years on numerous large drainage projects in the Wellington region. He began working as a contracts officer for Lower Hutt City Council. After a short time, he became contracts engineer LDEG Chair managing the Water Services division’s maintenance contracts for the city. In 2004 Tony moved north to the Manawatu area where he worked for Horizons Regional Council. Project manager for the construction of stormwater pump stations on the lower Manawatu drainage scheme. The work also included managing farm drainage schemes and stop-bank maintenance. After 4 years working at Horizons Tony moved to his current position as Developments Team Leader with Palmerston North City Council. Tony enjoys the challenge of working with the development community and ensuring that a consistently high standard of infrastructure is achieved. Outside of work Tony’s passions are playing music and woodwork using recycled NZ wood. Northern Representative Glenn Broadbent (Auckland Council) Glenn lead a small team of engineers responsible for the approval of land development, concepts and physical works, in the Albany Basin and Eastern Bays of North Shore before shifting to Auckland City Environments business unit to learn more about subdivisions within an urban environment. Glenn foresaw the benefits of creating a team of engineers that would provide the engineering input to consents and created the first Development Engineering team at Auckland Council in 1997. -

Hawkes Bay Wood Energy Industrial Symbiosis Project – Aim 3 Resource Convergence Opportunities

Assessment of wood processing opportunities aligned with industrial heat demand in Hawkes Bay Wood Energy Industrial symbiosis project – Aim 3 resource convergence opportunities Peter Hall & Barbara Hock (i) Report information sheet Report title Assessment of wood processing opportunities aligned with industrial heat demand in Hawkes Bay Authors Peter Hall & Barbara Hock Scion Client MBIE MBIE contract PROP-37659-EMTR-FRI number SIDNEY output 60404 number ISBN Number Signed off by Paul Bennett Date March 2018 Confidentiality Confidential (for client use only) requirement Intellectual © New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited. All rights reserved. Unless property permitted by contract or law, no part of this work may be reproduced, stored or copied in any form or by any means without the express permission of the New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited (trading as Scion). Disclaimer The information and opinions provided in the Report have been prepared for the Client and its specified purposes. Accordingly, any person other than the Client uses the information and opinions in this report entirely at its own risk. The Report has been provided in good faith and on the basis that reasonable endeavours have been made to be accurate and not misleading and to exercise reasonable care, skill and judgment in providing such information and opinions. Neither Scion, nor any of its employees, officers, contractors, agents or other persons acting on its behalf or under its control accepts any responsibility or liability in respect of any information or opinions provided in this Report. Published by: Scion, 49 Sala Street, Private Bag 3020, Rotorua 3046, New Zealand. www.scionresearch.com 2 Executive summary This report presents analyses of the current and projected wood resource and wood processing along with existing heat demand in Hawkes Bay with the aim of identifying wood energy industrial symbiosis opportunities.