Walker 32..49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

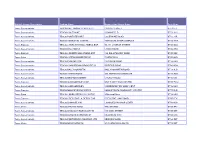

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number and Street Name

Multiple Group Description Trading Name Number And Street Name Post Code Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMONEY CASTLE ST CASTLE STREET BT53 6JT Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COLERAINE 2 BANNFIELD BT52 1HU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTSTEWART COLERAINE ROAD BT55 7JR Tesco Supermarkets TESCO YORKGATE CENTRE YORKGATE SHOP COMPLEX BT15 1WA Tesco Express TESCO CHURCH ST BALLYMENA EXP 99-111 CHURCH STREET BT43 8DG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYMENA LARNE ROAD BT42 3HB Tesco Express TESCO CARNINY BALLYMENA EXP 144 BALLYMONEY ROAD BT43 5BZ Tesco Extra TESCO ANTRIM MASSEREENE CASTLEWAY BT41 4AB Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ENNISKILLEN 11 DUBLIN ROAD BT74 6HN Tesco Supermarkets TESCO COOKSTOWN BROADFIELD ORRITOR ROAD BT80 8BH Tesco Supermarkets TESCO BALLYGOMARTIN BALLYGOMARTIN ROAD BT13 3LD Tesco Supermarkets TESCO ANTRIM ROAD 405 ANTRIM RD STORE439 BT15 3BG Tesco Supermarkets TESCO NEWTOWNABBEY CHURCH ROAD BT36 6YJ Tesco Express TESCO GLENGORMLEY EXP UNIT 5 MAYFIELD CENTRE BT36 7WU Tesco Supermarkets TESCO GLENGORMLEY CARNMONEY RD SHOP CENT BT36 6HD Tesco Express TESCO MONKSTOWN EXPRES MONKSTOWN COMMUNITY CENTRE BT37 0LG Tesco Extra TESCO CARRICKFERGUS CASTLE 8 Minorca Place BT38 8AU Tesco Express TESCO CRESCENT LK DERRY EXP CRESCENT LINK ROAD BT47 5FX Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LISNAGELVIN LISNAGELVIN SHOP CENTR BT47 6DA Tesco Metro TESCO STRAND ROAD THE STRAND BT48 7PY Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LIMAVADY ROEVALLEY NI 119 MAIN STREET BT49 0ET Tesco Supermarkets TESCO LURGAN CARNEGIE ST MILLENIUM WAY BT66 6AS Tesco Supermarkets TESCO PORTADOWN MEADOW CTR MEADOW -

The Justices of the Peace and the Administration of Local

THE JUSTICES OF THE PEACE AND THE ADMINISTRATION OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE EAST AND WEST RIDINGS OF YORKSHIRE BETWEEN 1680 AND 1750. Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The School of History, Michael Eric Watts Maddison. The University of Leeds. April 1986. ABSTRACT. The purpose of this thesis is to examine the criminal, civil and administrative work of the county magistrates of the East and West Ridings of Yorkshire between 1680 and 1750. There is a distinct lack of regional studies for this period, though much has been written about the county community during the era of the English Revolution of the mid seventeenth century and about the effect upon local society of the industrialisation of the late eighteenth century. This is a serious omission for late Stuart and early Georgian times comprise a vital period in the development of local government. It was a time when the country gentlemen who acted as Justices of the Peace were most autonomous. Yet it was also a period which witnessed some fundamental and permanent changes in the organisation and administration of local government. The thesis is divided into two. The first section contains four chapters and deals with the structure of local government. The general organisation at county level is explained, and the backgrounds, interests and attitudes of the actual individuals who served as magistrates are closely examined. An analysis is also undertaken of the relationship between the Justices and central government, and special emphasis is placed on the attitudes of the Crown and Privy Council towards the membership of the commission of the peace and on the role of the Lords Lieutenant and the Assize Judges. -

Topography of Great Britain Or, British Traveller's Pocket Directory : Being

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES TOPOGRAPHY OF iHteat Mvitai% tT' OR, BRITISH TRAVELLER'S POCKET DIRECTORY; BEIN& AN ACCDRATE AND COMPREHENSIVE TOPOGRAPHICAL AND STATISTICAL DESCRIPTION OF ALL THE COUNTIES IN WITH THE ADJACENT ISLANDS: ILLUSTRATED WITH MAPS OF THE COUNTIES, WHICH FORM A COMPLETE BRITISH ATLAS. BY G. A. COOKE, ESQ. VOL. XXL CONTAININ& YORKSHIRE. Printed, by Assignment from the Executors of the late C. Cooke, FOR SHERWOOD, NEELY, AND JONES, PATERNOSTER-ROWj; AND SOLD BY ALL UOOKSELLERS. TOPOGRAPHICAL AND STATISTICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTY OF YORK; Containing an Account of its Situation, li. M'Millan, Printer. Bow-Street, Covent-Gavdcn. C3) A Ti^ABLE OF THE PRINCIPAL TOWNS IN THE S2!le3t KiDittg of pork$i}ire; Their Distance from London, Markets, Houses, and Inhabitants r=^ with the Time of the Arrival and Departure of the Post. Towns. Dist. Markets. Houses, Inhabi- Post tants. amves. Aberford 186 Wed. 176 922 Barnsley 176 Wed. 954 5014 12| m. Bawtry 153 Wed. 178 918 4f aft. Bingley 206 Tuesd. 931 4782 7 m. Boroughbridge 206 Sat. 131 747 llf m. Bradford 196 Thurs. 548 2989 5im. Dent 266 Friday. 379 1663 Dewsbury 187 Wed. 987 5509 Doncaster 162 Sat. 1438 6935 6 aft. Gisburn 224 Monday, 100 509 Halifax 197 Sat. 501 £677 41 m. Huddersfield . 189 Tuesd. 1871 9671 3im. Keighley 209 Wed. 1367 6864 84 ra. Kettlewell 233 Thurs. 125 361 Knaresborough 202 Wed. 888 4234 7 m. Leeds ... ., 193 Tu. Sat. 12,240 62,534 3|m. Otley 205 Friday. 530 2602 Pontefract 177 Sat. -

A & C Black Ltd, 35 Bedford Row, London WC IR 4JH (01-242-0946

365 A A & C Black Ltd, 35 Bedford Row, London WC IR 4JH (01-242-0946) Academy of Sciences, Frescati, s-10405 Stockholm 50, Sweden Accepting Houses Committee, I Crutched Friars, London EC3 (0 1-481-2120) Access, 7 StMartin's Place, London WC2 (01-839-7090) Acupuncture Association and Register Ltd, 34 Alderney St, London SWIV 4EU (01-834-1012) Advertising Standards Authority, 15-17 Bridgemount St, London WCIE 7AW (01-580--0801) Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service, Head Office, Cleland House, Page St, London SW 1P 4ND (01-222-4383) Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service Regional Offices --Midlands, Alpha Tower, Suffolk St Queensway, Birmingham Bl ITZ (021-643-9911) --North West, Boulton House, 17-21 Charlton St, Manchester Ml 3HY (061-228-3222) --Northern, Westgate House, Westgate Rd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne NEI ITJ (0632-612191) --Scotland, 109 Waterloo St, Glasgow, G2 ?BY (041-221-6832) --South East, Hanway House, Red Lion Sq, London WCIR 4NH (01-405-8454) --South West, 16 Park Place, Clifton, Bristol BS8 IJP (0272-211921) --Wales, 2-4 Park Grove, CardiffCFl 3QY (0222-45231) --Yorkshire and Humberside, City House, Leeds LSI 4JH (0532-38232) Advisory Council on Public Records, Public Record Office, Chancery Lane, London WC2A ILR (01-405-0741) Advisory Welsh Translations Panel, Oxford House, Cardiff(0222-44171) Afghanistan, Embassy of the Republic of, 31 Prince's Gate, London SW7 1QQ (0 1-589-8891) African Violet Society of America, 4988 Schollmeyer Ave, StLouis, Mo 63109, USA Agricultural Credit Corporation Ltd, Agricultural -

USER GUIDE 11 Sources for Family Historians

USER GUIDE 11 Sources for Family Historians Contacting Us This guide will help to explain some of the more commonly used records for researching family history, including some Please contact us to book a place useful records which are not held by West Yorkshire before visiting our searchrooms. Archive Service [WYAS]. WYAS Bradford Please contact us using the ‘contact us’ details if you would Margaret McMillan Tower Prince’s Way like to visit WYAS to look at any of the records we do hold Bradford that are mentioned in this guide. BD1 1NN Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0152 There is no charge for personal visits to our searchrooms e. [email protected] except for copies of documents and photography fees. We WYAS Calderdale can also arrange for groups visits and offer a 30 minute Central Library & Archives research service. Square Road Halifax HX1 1QG If you are researching local history you may wish to look at Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0151 User Guide 16 ‘Sources for Local Historians’ User Guide e. [email protected] 10 ‘Sources for House History’ and User Guide 7 ‘West WYAS Kirklees Riding Registry of Deeds Service for Family and Local Central Library Historians’ are useful if you are researching the history of a Princess Alexandra Walk building. Huddersfield HD1 2SU In this guide you will find information on: Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0150 e. [email protected] Getting started [Civil registration and census] WYAS Leeds Pre 1837 registration records Nepshaw Lane South Leeds Wills LS27 7JQ School records Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0155 Adoption e. -

Agenda Document for Licensing Sub-Committee, 26/03/2019 10:00

Public Document Pack LICENSING SUB-COMMITTEE MEETING TO BE HELD IN CIVIC HALL, LEEDS ON TUESDAY, 26TH MARCH, 2019 AT 10.00 AM MEMBERSHIP Councillors P Drinkwater - Killingbeck and Seacroft; Two Members to be confirmed Enquiries specific to Agenda compiled by: Entertainment Licensing: Governance and Scrutiny Support Stephen Holder Civic Hall Tel No: 0113 3785332 LEEDS LS1 1UR Tel No: 0113 3788662 Produced on Recycled Paper A CONFIDENTIAL AND EXEMPT ITEMS The reason for confidentiality or exemption is stated on the agenda and on each of the reports in terms of Access to Information Procedure Rules 9.2 or 10.4(1) to (7). The number or numbers stated in the agenda and reports correspond to the reasons for exemption / confidentiality below: 9.0 Confidential information – requirement to exclude public access 9.1 The public must be excluded from meetings whenever it is likely in view of the nature of the business to be transacted or the nature of the proceedings that confidential information would be disclosed. Likewise, public access to reports, background papers, and minutes will also be excluded. 9.2 Confidential information means (a) information given to the Council by a Government Department on terms which forbid its public disclosure or (b) information the disclosure of which to the public is prohibited by or under another Act or by Court Order. Generally personal information which identifies an individual, must not be disclosed under the data protection and human rights rules. 10.0 Exempt information – discretion to exclude public access -

Optimising Cost Reduction, Delivering the Best Future Estate

Provision of Property Services to the Government Property Unit Mini-Competition Response 12 August 2011 Optimising cost reduction, delivering the best future estate London & Bristol Property Vehicle Pilot 10 January 2011 Mr P Mayes Government Property Unit Department for Business, Innovation & Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET. by e-mail: [email protected] London, 12th August 2011 Dear Paul, Provision of Property Services to the Government Property Unit Thank you for your brief. I am pleased to say that we can offer in response a service which plays to some of our particular strengths. We have assembled dedicated regional account teams to give you the advice and market presence you need to help transform the government estate. We are using senior skilled professionals to identify, create, and seize early and sustainable savings and value opportunities, and to give you the strategic insight required to deliver the right future estate for efficient government operations. You need best in class advice in each region. We provide this via full service offices including those in each of your priority cities. Because these are run along national service lines, not by geography, best practice, skilled resource, and market information are shared between them, to your advantage in both sharper advice and implementation. We capture in our team the insights form our current instructions with you, and offer fifteen specific efficiencies which will help us quickly mobilise and give you rapid, effective and consistent advice. Our culture is built on teamwork and collaboration which we are convinced delivers you the best results, and will be essential on a multidisciplinary task such as this. -

Aristocratic Whig Politics in Early-Victorian Yorkshire: Lord Morpeth and His World

ARISTOCRATIC WHIG POLITICS IN EARLY-VICTORIAN YORKSHIRE: LORD MORPETH AND HIS WORLD David Christopher Gent Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of York Department of History 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the provincial life of George W. F. Howard (1802-64), 7th Earl of Carlisle, better known as the early-Victorian Whig aristocrat and politician Lord Morpeth. It challenges accounts which have presented Whiggery as metropolitan in ethos, by demonstrating that Morpeth strongly engaged with the county of Yorkshire as a politician, philanthropist and landlord. It provides the first dedicated account of how Whiggery operated, and was perceived, in a provincial setting. An introduction summarises the current historiography on the Whigs, and establishes the rationale behind the study. Chapter One details the pivotal influence of Morpeth’s Christian faith on his thought. It suggests that his religious values shaped both his non- political and political actions, ensuring a correlation between them. Chapters Two and Four are concerned with Morpeth’s career as M.P. for Yorkshire (1830-32) and the West Riding (1832-41, 1846-48). They suggest that Morpeth played a key role in building an alliance between the region’s liberals and Whiggery, based around the idea that the Whigs would offer political, economic and ecclesiastical reforms. However, they show how this alliance gradually splintered, partly owing to differences between the Whigs and some of the region’s nonconformist liberals over issues of Church and State and the Whigs’ social reform policies. Chapter Three details Morpeth’s activities as a philanthropist in the county. It suggests that this maintained his links to his supporters, shaped his views on social questions, and enhanced his political reputation. -

Bradford Multiplex Broadcasting Corporation Limited

List of local Bradford & Neighboring Cities Internet, Community and Commercial Radio Stations, given consent to join Bradford Multiplex Broadcasting Corporation Limited 1: Radio Station’s Name: Bradford Asian Radio 1413 AM/MW Radio Station’s Address: Suite 23, 8th Floor, West Riding Business Centre Cheapside Bradford BD1 4HR Wesite: bradfordasianradio.co.uk 2: Radio Station’s Name: Radio Royal Bradford (Absolutely free carriage has been offered) Radio Station’s Address: Radio Royal Bradford, Bradford Royal Infirmary, Duckworth Lane, Bradford, BD9 6RJ Wesite: radioroyal.co.uk 3: Radio Station’s Name: St. Luke's Sound (Absolutely free carriage has been offered) Radio Station’s Address: Little Horton Bradford D5 0NA Website: stlukessound.co.uk 4: Radio Station’s Name: Radio Ram Air (Absolutely free carriage has been offered) Radio Station’s Address: University of Bradford Richmond Road BD7 1DP Website: ramair.co.uk 5: Radio Station’s Name: Keighley On Air Radio Station’s Address: Melbourne House, Chesham Street. Keighley BD21 4LG Website: keighleyonaire.co.uk 6: Radio Station’s Name: WORTH VALLEY COMMUNITY RADIO Radio Station’s Address: 2-4 West Lane, Haworth, Keighley, England, BD22 8EF Website: wvcr.org.uk 7: Radio Station’s Name: Asian Radio Online Radio Station’s Address: 196 Birch Lane, Bradford, West Yorkshire, BD5 8PF Website: asianradio.online 8: Radio Station’s Name: Pakistan Fm Bradford Radio Station’s Address: Suite 17, 8th Floor West Riding House Bradford BD1 4HR Website: pakistanfm.co.uk 9: Radio Station’s Name: Plusnewstv.tv -

Steer Davies Gleave's Socio-Economic Baseline Report

APPENDIX 8 Leeds Socio-Economic Baseline Report Report July 2009 Prepared for: Prepared by: Metro and Leeds City Council Steer Davies Gleave West Riding House 67 Albion Street Leeds LS1 5AA +44 (0)113 389 6400 www.steerdaviesgleave.com Contents Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 POPULATION 3 3 ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 7 Employment 7 Economic inactivity 8 4 DEPRIVATION 13 5 TRANSPORT CHARACTERISTICS 19 Transport Needs Index 21 FIGURES Figure 1.1 The City of Leeds within West Yorkshire 1 Figure 1.2 Leeds ward map - at the time of the 2001 Census 2 Figure 1.3 Leeds ward map – current (established 2004) 2 Figure 2.1 Population growth in the City of Leeds 3 Figure 2.2 West Yorkshire population densities 4 Figure 3.1 Locations of the largest employers in Leeds 8 Figure 3.2 Job Seeker Allowance Claimants 11 Figure 4.1 Index of Multiple Deprivation 13 Figure 4.2 Income deprivation 14 Figure 4.3 Employment deprivation 14 Figure 4.4 Health deprivation 15 Figure 4.5 Education deprivation 15 Figure 4.6 Housing deprivation 16 Figure 4.7 Living environment deprivation 16 Figure 4.8 Crime deprivation 17 Figure 5.1 Car ownership 20 Figure 5.2 Transport Needs Index in Leeds 22 TABLES Table 2-1 West Yorkshire Districts 3 Contents Table 2-2 Age of population 4 Table 2-3 Population aged 19 years old and under 5 Table 3-1 Jobs by industry 7 Table 3-2 Employment growth 8 Table 3-3 Economic inactivity 9 Table 3-4 Unemployment 10 Table 5-1 Car ownership 19 Table 5-2 % of households with no car or van 19 Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 This report provides a description of the socio-economic characteristics of the City of Leeds. -

4260 the London Gazette, 22Nd April 1969

4260 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 22ND APRIL 1969 residing at 560, BexhiM Road, St. Leonards-on- per £—6s. 4d. (making 20s. in all) together with Sea, and previously carrying on business as an 4 per cent. Statutory Interest. First or Final, or Electrical Contractor at 1, Tynevak Terrace, otherwise—Third and Final. When Payable—9th Lemington-on-Tyne in the county of Northumber- May, 1969. Where Payable—The Official Receiver's land, now Electrician. Court—HASTINGS. Office, Prospect House, 94, Regent Road. Leicester, No. of Matter—10 of 1955. Amount per £— LEI 7DE. 3s. lOd. First or Final, or otherwise—Fifth and Final. When Payable—9th May, 1969. Where PONT, Joseph Stephen, of 14, Keithley Walk, Liver- Payable—7, Old Steine, Brighton, BN1 1GA. pool, 24 in the county of Lancaster, Transport Driver, lately carrying on business from 14, Keithley COX, Kenneth Leonard, of 44, The Dashes, Harlow Walk aforesaid, as a MOBILE GROCER. Court— in the county of Essex, a Driver and GODLE- LIVERPOOL. No. of Matter—104 of 1961. MAN, Ivan Roy, of 74, The Hides, Hairlow Amount per £—2s. First or Final, or otherwise— in the county of Essex, a Sales Inspector, lately Supplemental. When Payable—7th May, 1969. carrying on business in partnership at 14, Market Where Payable—Official Receiver's Office, West Street, Olid Harlow in the county of Essex under Africa House, 25, Water Street, Liverpool, L2 ORO. the style of Harlow Motorcycles (Joint Estate). Court—HERTFORD. No. of Matter—15 of 1962. WOOD, Frank, residing at 8, Kinver Road, Moston, Amount per £—4s. 9|d. -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, Lorn NOVEMBER 1983

14876 THE LONDON GAZETTE, lOrn NOVEMBER 1983 FIRST MEETINGS AND PUBLIC EXAMINATIONS DARLINGTON. No. of Matter—28 of 1983. Date of First Meeting—21st November 1983. 11 a.m. Place— WILLIAMS, Richard Geraint, of 39 High Street, Bryng- Official Receiver's Office, Bayheath House, Prince Regent wran, Anglesey, MOTOR TRADER, lately carrying on Street, Stockton-on-Tees, Cleveland. Date of Public business from Central Garage, High Street, Bryngwran, Examination—17th January 1984. 10.30 a.m. Place— Anglesey. Court—BANGOR. No. of Matter—37 of The Court House, 4 Coniscliffe Road, Darlington, Co. 1983. Date of First Meeting—23rd November 1983. Durham. 10.45 a.m. Place—The Official Receiver's Office, Dee Hills Park, Chester. Date of Public Examination—9th INNES, James William Dunbar, Pipe Lines Superinten- December 1983. 2.15 p.m. Place—The Court House dent, residing at 160 Beckett Road, Wheatley, Don- (Police Station), Garth Road, Bangor. caster in the county of South Yorkshire lately residing and carrying on business as a PUBLICAN at The Star KIPLING, Robert Arthur (described in the Receiving Inn, North Dalton in the county of North Humberside Order as R. A. Kipling (male)), residing at 66 Brook- and formerly residing at 143 Bawtry Road, Doncaster lands Crescent, Havercroft and previously residing at 6 aforesaid. Court—DONCASTER. No. of Matter—29 Centre Street, Hemsworth, both in the county of West of 1983. Date of First Meeting—24th November 1983. Yorkshire, TURKEY SHED OPERATOR. Court— 11 a.m. Place—Official Receiver's Office, 8-12 Furnival BARNSLEY. No. of Matter—15 of 1983.